In May, the UK will be holding the EU elections that were never meant to be. As Luke Cooper writes, Brexit’s polarization of British politics is reconfiguring the party landscape. In the recent local elections, smaller parties and independent candidates appeared to benefit from the divide running through both Conservative and Labour. However, the EU elections will provide the first real picture since the start of the Brexit negotiations of the will of the British electorate. Uniquely in UK history, the elections will also be predominantly about Europe itself. If the pro-Remain parties and candidates can channel the new Europhilia into a substantial debate on the UK’s future in Europe, then past precedent may be reversed. More likely, however, is that the elections will be seen as a re-run of the Brexit referendum, in which case the Eurosceptic vote will again be strong – causing problems for the rest of the EU.

In Denmark, which like Britain joined the EU in 1973, the EU elections are being overshadowed by the national elections in the Summer. As on previous occasions, the main issue on the national level is immigration. While in opposition, Denmark’s Social Democrats have been moving rightwards, and are expected to return to power after their defeat in 2015. One hope for the EU elections is that growing awareness of the need for transnational responses to climate change may result in more engagement, writes Kristoffer Granov.

Malta, Europe’s smallest member state, has been subject to intense international scrutiny since the assassination of Daphne Caruana Galizia in 2017. However, the criticism has instead served to strengthen the position of the governing Labour party and its charismatic prime minister, Joseph Muscat. As long the Maltese economy remains strong, writes Herman Grech, people will continue to vote for whoever best protects the country’s interests on the European stage.

UK: The EU elections that were never meant to be

Luke Cooper, political scientist, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, IWM Vienna

The British government’s reluctant acceptance that the country will participate in the European Elections, having failed to establish parliamentary support for the UK–EU Brexit deal, has set the stage for a unique political moment. Unlike in the 27 other EU states, Britain will be electing representatives to an institution that, formally at least, it plans to leave.

Even by the ruthless standards of adversarial, democratic politics, the UK’s newly elected MEPs will have to cope with a very high level of job insecurity, establishing offices and living arrangements that could be terminated with just one month’s notice should the UK Parliament pass the Brexit deal. However, the circumstances surrounding the election can give confidence to MEPs hoping to sit their full terms. The chances of Brexit now happening look increasingly remote.

How does this reconcile itself with the high-profile launch, and popularity in opinion polls, of Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party? Paradoxically, the radicalization of the Leave vote around a far-right pole that is opposed to May’s deal, but aggressively supportive of a ‘no deal’ Brexit, diminishes the prospect of Britain ever leaving the EU. If there is no pragmatic form of Brexit capable of satisfying its most enthusiastic supporters, then the project will inevitably hit the buffers. Britain may now be experiencing this epiphany.

This situation illustrates the importance of the performative, symbolic and rhetorical as animating features of Brexit. It is a political desire and conviction that feeds primarily on what Raymond Williams referred to as a ‘structure of feeling’: a set of emotions that derive from a belief in sovereignty (the ‘take back control’ adage) combined with a sense of fear and threat regarding the presence of migrants. By voting down the Brexit on offer, the Brexiter is tacitly stating the following preference: better glorious defeat, and with it the eternal possibility of claiming that the ‘new Jerusalem’ was stolen, rather than facing the reality of Brexit Britain.

EU elections prospects: Europhiles versus Brexiteers

The European elections follow shortly after local municipality elections, which saw a rise in support for Remain parties, and a loss of support for the two largest parties, Labour and the Conservatives. While Nigel Farage’s Brexit Party was not standing in the local elections, some of this vote may have gone to independent candidates (who gained 606 council seats). This illustrates how Britain has polarized between Leave and Remain, reducing scope for a cross-party compromise. Labour, in particular, would be acutely exposed to signing off a Brexit deal with the Tories. Such a move would not only risk the incandescence of its Remain voters, but also undermine the anti-Tory credentials of the leftwing Labour leadership.

For the parties aligned to the Remain side of the Brexit cleavage, the European elections have been met with a mixture of excitement and trepidation. Rightly or not, the elections will inevitably be treated as an indication of the relative strengths of the Remain and Leave camps. The anti-Brexit parties see an opportunity. It will be the first electoral test of Change UK, a centrist party formed after a split by a small group of Labour and Conservative MPs. They will need to finish higher than the existing party of the centre, the Liberal Democrats, to maximize their clout in the inevitable merger talks ahead. The latter’s impressive local election results, which saw them take over 700 council seats and 19 per cent of the vote, have already put them in a stronger position. For the Labour Party, whose voters, party members and MEP candidates are overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit, the elections will create significant pressure to coalesce around an unambiguous ‘Remain and Reform’ platform. If it fails to move in this direction, Labour can expect to lose significant numbers of voters to the insurgent Green Party, which has just had its best local election results in decades. Given the Labour leadership’s current position, this looks likely.

While Europe has always had a high efficacy for eurosceptic parties, which have tended to get strong results in EU elections, it will now become a preoccupation in the tussle between Labour and the Conservatives Party too. Whereas European elections would previously have been seen as a proxy for the record of the governing party, European issues now dominate the British electoral landscape like never before.

Indeed, a further curiosity of Brexit lies in how it has ignited a huge pro-European civil society movement. This is a development of great historical novelty in UK politics. For many people, being part of Europe was taken for granted and only registered as an emotional commitment when it appeared lost. Previously, the UK not only lacked a consensus in favour of European integration, but also tended to conceive the relationship to the union in largely transactional and self-interested terms. Even amongst the more Europhile of citizens and politicians, it was rare to find a passionate belief in a united Europe. Brexit has caused this to change.

Despite the politicization of the European issue on all sides, some problematic aspects of how Britain has traditionally approached the EU persist. Unlike in other countries, there is no culture of spitzenkandidaten (‘lead candidates’), which would see national parties identify a top candidate among prospective MEPs to give them greater public prominence (although parties do select leaders in the European Parliament itself). Consequently, there are no television debates organised between them. The British media, including politically impartial broadcasters such as the BBC, ITV and Channel 4, give a great deal of coverage to prominent Eurosceptic MEPs, while largely ignoring the hard work of the Europhile on behalf of their constituents. Neither is any media attention given to the international spitzenkandidaten debates, amongst candidates for the Presidency for the European Commission from the various international party groupings in the European Parliament. While in more traditionally Europhile countries, the names of the European parliamentary groups are well known, they are largely invisible in UK domestic politics. As a result, even on the Remain side, debate on the EU and the EU elections very often remains mired in an underlying national parochialism.

Remain-orientated parts of British civil society, and amongst the political parties, have a responsibility to address and overcome these issues. If the EU elections become a re-run of the referendum, and the simplistic choice of ‘Leave’ or ‘Remain’, this will surely favour Nigel Farage’s new Brexit Party. But if, instead, they become about the kind of Europe that Britons would like to participate in building, in other words about what remaining might mean in practice, then a more positive outcome for Europe could emerge.

Denmark: Between rightward drift and ecological turn

Kristoffer Granov, Editor, ATLAS Magazine, Copenhagen

With a general election due to take place in Denmark by mid-summer, the focus of public debate is very much on this rather than European elections in May. As has been the case for the last fifteen years, the central issue once again looks to be immigration. The Social Democrats, the self-proclaimed builders of the welfare state and currently the largest parliamentary faction, are expected to be returned to power after failing to enter government in 2015. Since then, under the leadership of Mette Frederiksen, the party has taken a sharp turn to the right. The party has been losing voters for years to the nationalist Danish People’s Party (DPP), but now seems to have found a solution in simply copying the policy and rhetoric of its competitor. Whether the Social Democrats will also emulate the DPP’s Euroscepticism remains to be seen.

Unlike in most other EU member states, Denmark does not have to contend with larger structural economic difficulties, which may make the Danish national conversation seem somewhat provincial to an outsider. However, the candidates for the European Parliament do focus more on transnational issues, such as the regulation of financial markets and curbing the influence of the world’s largest tech companies.

The exception to the Danish public’s lack of interest in European issues could turn out to be climate change. Most agree that the issue respects no borders and that it would be pointless to try to solve it nationally. It seems that the parties are evolving accordingly, whether due to a realization of the gravity of the issue or a more cynical calculation triggered by people’s genuine concern, particularly among younger generations.

Since the exact date of the national election is as yet unknown, there is still a chance that the Danish prime minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen will decide to schedule it to coincide with European elections. Should that be the case, it will affect voter turnout significantly. If not, there is a serious risk that coverage of and interest in the European elections will suffer from all the attention being paid to the general election.

Malta: Weathering the storm of criticism

Herman Grech, Journalist, Times of Malta, Valletta

On 25 March, Portuguese MEP Ana Gomes stood up in the Chamber of the European Parliament in Strasbourg and accused Maltese prime minister Joseph Muscat of ‘continuing’ to protect the murderers of investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia. The socialist MEP’s wild claim, made during a debate on the rule of law in Malta, sparked a political storm on the Mediterranean island.

In the international arena, the image of Malta as a sun-drenched destination with a rich history may have morphed into one of a tax-haven rife with impunity and nepotism. But the feeling among the majority of the island’s electorate is different.

The one thing that is certain about the European elections in the EU’s smallest member state is that the ruling Labour Party will win. According to the latest opinion polls, it is predicted to do so with ease, taking at least four of the six available seats.

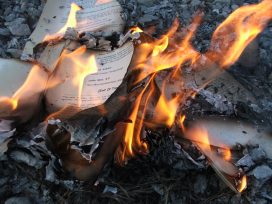

The EP election comes 18 months after Caruana Galizia was killed by a car bomb in the sleepy village of Bidnija, sending Malta into an unprecedented downward spiral of institutional distrust. The murder occurred shortly after the Panama Papers had revealed that two senior government officials held secret offshore accounts. Three men have since been charged with the murder, but its mastermind remains at large.

The corruption claims and murder point towards deeper structural flaws in Malta, as documented in a damning report released by MEPs shortly after Caruana Galizia’s death. They cite serious concerns about the country’s legal system and separation of powers, as well as its ‘weak implementation’ of anti-money laundering legislation. In fact, for the last three years, Malta’s leaders have repeatedly been summoned to Brussels and Strasbourg to respond to an onslaught of accusations that often imply Malta is akin to a banana republic.

Responding to Gomes in Malta’s defence, socialist MEP and former prime minister Alfred Sant insisted that issues about the rule of law were being used to advance what he termed ‘polarized and biased interests’ arising from national politics. David Casa, MEP for the opposition Nationalist Party said: ‘I and others calling for accountability have been labelled “traitors” deserving of punishment. It is what happens when institutions are captured, impunity flourishes, and corrupt politicians substitute themselves for the state.’ However, the European Parliament’s criticism since appears to have strengthened the current Labour government’s grip on power.

The Teflon prime minister presiding over a thriving economy

There are other reasons why Labour is expected to dominate in the European elections. First, Muscat is a charismatic leader and a powerful orator often referred to as the ‘Teflon prime minister’, since he appears to have the flair to brush off any scandal with impeccable ease – at least in his supporters’ eyes.

Second, the opposition centre-right Nationalist Party is led by a man whom many within his own party refuse to acknowledge as leader. Adrian Delia has failed to make inroads into the massive defeat sustained by his predecessor in June 2017. Many of Delia’s biggest critics have already publicly declared they will abstain from voting in May to try to force him to step down.

Third, the island of almost half a million inhabitants is experiencing a financial boom. Buoyed by thriving tourism and online gambling sectors, as well as a controversial construction industry, Malta’s pace of economic growth would make mouths water in most EU states. The contentious Individual Investment Programme – a cash-for-passports scheme – has also boosted Malta’s coffers to the tune of millions.

Between the smaller parties and the European stage

There are several candidates representing smaller parties, including Malta’s first openly pro-choice candidate. The LGBT activist Mina Tolu is running for the Greens and calling for the decriminalization of abortion.

Migration remains a hot potato in one of the southernmost EU member states and the two main parties are now on equal rhetorical footing. Self-styled ‘racialist’ and Nazi sympathiser Norman Lowell, who once suggested migrants’ boats should be sunk 14 miles from shore, is once again running for election. But in an electoral system engineered to favour the two big parties, he is unlikely to win a seat.

Ultimately, the electorate cares about who will protect Malta’s interests on the European stage – an issue that ultimately depends on which side of the fence they sit. The EU certainly has the tiny republic on its radar at the moment. However, though the European Parliament’s criticism has not stoked any resentment towards Brussels, Malta is expected to look inwards once again and vote along traditional party lines.

Read a more extensive version of Herman Grech’s commentary in VOXeurop, where it first appeared.

‘Mood of the Union’ is published by Eurozine and sponsored by the ERSTE Foundation and the National Endowment for Democracy.