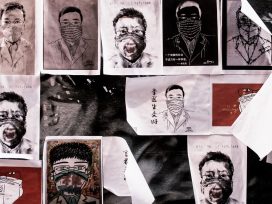

Postmodern ideas have gained the status of absolute truths. Relativism, selectively appropriated into the language of both left and right politics, has metamorphosed into dogma. As oversimplification distorts communication, public trust in scientific fact has eroded. Could renewed ideas of objectivity be a way out?