Could there be a dictatorship inside the European Union? If such a spectre appeared, should Brussels somehow step in to shore up democracy? Or would this constitute an illegitimate form of meddling in the domestic affairs of countries which, after all, have delegated only specific powers to Europe – and not empowered Brussels to be a policeman for liberal democracy across the European continent, or even just to lecture Europeans from Lapland to Lampedusa on how popular rule is correctly understood? All these are no longer theoretical questions: recent developments in Hungary and Romania have put such challenges squarely on the agenda of European politics – even if concerns about a possible slide towards illiberal democracy in both countries have been largely overshadowed by the eurocrisis.

I propose that it is legitimate for Brussels to interfere in individual member states for the purpose of protecting liberal democracy. Four common concerns about such interventions are misplaced: first, the criticism that they are hypocritical because the Union is itself not democratic and therefore in no position credibly to act as the guardian of democracy on the continent; second, the worry that there is no single, fully agreed model of European liberal democracy that could be used as a template to decide whether countries are departing from shared “European standards”; third, the concern that such interventions themselves are in and of themselves paternalistic and, ultimately, illiberal; and, finally, the charge that only smaller, relatively powerless member states would ever be subject to interference from.

These are reasonable enough concerns. But one can counter them and in the process develop a set of criteria as to when and how European intervention is justified. In fact, the real problem arises not at a relatively abstract theoretical level, but when it comes to policy instruments and concrete political strategies. To say it outright: as of now, the EU has no convincing tool kit to deal with situations which probably not many eurocrats – or, for that matter, European elites more broadly – ever foresaw. Brussels, as well as national capitals, seemed to have assumed that the consolidation of liberal democracies in the run-up to EU accession was irreversible. Once inside the club, so the rather complacent reasoning seemed to go, young democracies would count their blessings and never look back (or, for that matter, sideways and forward to illiberal forms of statecraft). To be sure, the repertoire of legal and political instruments the EU has at its disposal at the moment to exert pressure on member states might occasionally work – but it can also appear arbitrary and opportunistic. I propose extending this repertoire as well as the creation of a new kind of democracy watchdog – tentatively called the “Copenhagen Commission” – which can raise a Europe-wide alarm about deteriorations in the rule of law and democracy.

Four worries

The first commonly heard charge against the EU protecting democracy is that the Union itself is not democratic – hence Brussels is fundamentally hypocritical in speaking out for and in the name of values to which it itself does not adhere. This charge misses the point that the Union derives its legitimacy not from being a continent-wide democracy. Rather, it is legitimate because national parliaments have freely voted to bind themselves and follow European rules. In the eurocrisis this logic of self-binding is clearly under attack – investors have not found this model credible. But with the single market it has worked well for decades: nobody is complaining about the fact that Brussels is taking member state governments to court for violating competition rules, for instance.

Moreover, one of the goals of European enlargement to the East was to consolidate liberal democracies (or, in the case of Bulgaria and, in particular, Romania, complete the transition to liberal democracy in the first place). Governments of the region in turn sought to lock themselves into Europe so as to prevent “backsliding”; it was like Ulysses binding himself to the mast in order to resist the siren songs of illiberal and antidemocratic demagogues in the future. Hence neither Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán nor Romanian Prime Minister Victor Ponta are right to accuse Brussels of some form of Euro-colonialism: Orbán, for instance, compared the EU to Turks, Habsburgs and Russians – former oppressors of the freedom-loving Magyars. In fact, “they” are only reminding the Hungarians and Romanians how they wanted to live when they joined the Union in 2004 and 2007 respectively.

One might still object that the parallel between interventions to safeguard the single market and interventions to protect democracy is misplaced. Is regulating the purity of beer or the length of cucumbers not a categorically different matter than the shape and form of national political institutions? Is European integration not predicated on the fact that member states remain both “masters of the treaties” and, in many clearly demarcated areas, masters of their own political fate? After all, the Lisbon Treaty itself enshrines the very principle that the Union ought to respect the national identities of the member states. And European leaders regularly trumpet European “diversity” not just as a fact – but as a distinct European value.

Praise for “diversity” inadvertently bolsters a second major concern about EU interventions, namely that there are in fact no shared European standards of liberal democracy and that hence all efforts to protect democracy in Europe are arbitrary. In short: there is indeed a single market – but no single model of democracy in the EU. This is where a more historical argument comes in: the whole direction of political development in post-war Europe has been towards delegating power to unelected institutions, constitutional courts in particular. And that development was based on specific lessons that Europeans – rightly or wrongly – drew from the political catastrophes of midcentury: in particular, never again should a parliament abdicate in favour of a Hitler or a Marshal Pétain, the leader of Vichy France, without any checks (and balances). Distrust of unrestrained popular sovereignty, or even unconstrained parliamentary sovereignty (what a German constitutional lawyer once called “parliamentary absolutism”) is, so to speak, in the very DNA of post-war European politics.

Of course, history is not destiny and its supposed lessons do not automatically generate legitimacy. But it seems a reasonable presumption that radical, sudden departures from this in large parts anti-majoritarian model require special justifications. This thought applies to Hungary, for instance, where the constitutional court and, in general, the independent institutions to which Hungary committed after 1989 are being systematically weakened. But it does not apply straightforwardly to a country like Britain, where de facto constraints on – in theory unlimited – parliamentary sovereignty have had a by and large more informal character.

Still, one might point out that, while European nation-states arrived at similar templates for what I have elsewhere called “constrained democracy”, they ultimately did so themselves – and attempts by Brussels now to preserve these arrangements for them are per se illiberal and paternalistic. Put simply: we should not help peoples who cannot help themselves, and we should not protect peoples from their own governments, short of extreme circumstances (above all, genocide). This overlooks that we (Europeans) are all already in this together, so to speak. All European citizens have an interest in not being faced with an illiberal member state in the EU, since that state will make decisions in the European Council and therefore, at least in an indirect way, govern the lives of all citizens. Strictly speaking, there are no purely internal affairs for EU member states; all EU citizens are affected by developments in a particular member state, as long as that country’s executive remains in the Council and keeps voting on European law. This fact of interdependence has been brought home to Europeans by the eurocrisis, but it has mostly been interpreted in financial and economic terms. Yet there is political interdependence, too.

So the intuitively plausible classical-liberal notion that we should not intervene in countries to promote political principles in which local people appear to have no interest or which they seem willing to abandon cannot be applied directly to the EU. Of course, if a member state wishes to disentangle itself from the other member states (and thus other European citizens), so be it. But that decision in itself has to be made in some sort of recognizably democratic way. Put simply: a full-fledged dictatorship should leave the EU, no matter what; but a democratic state that wants to leave still has an interest in democratic institutions staying intact – and therefore in Brussels reinforcing such institutions even in cases where the ultimate, democratic decision is one for exit.

All very well in theory, critics might say – but what about the danger that calls for intervention become the stuff of symbolic politics, or the danger that only small member states will ever be picked on? This is a common interpretation of what happened when EU states imposed bilateral sanctions on Austria, after the party of far-right populist leader Jörg Haider had entered the government in early 2000. Leaders like Jacques Chirac – unable to do much about Jean-Marie Le Pen’s National Front at home – could moralize about small countries at no cost internationally and attack domestic opponents at the same time. Meanwhile, nobody ever dared to touch Berlusconi’s Italy, no matter how much political bunga-bunga was going on. Powerful member states – and especially founding member states of the EU – appear to be above the law. This is a serious concern not about the justification of EU interventions as such, but about the prospect that in practice there will always be double standards.

However, it would be a mistake to conclude from a comparison between the cases of Italy, Austria, Hungary and Romania that only weaker new member states get picked on. For there are important differences here that also point to coherent criteria as to what would make EU interventions legitimate. The problem with the “Haider Affair” was partly that sanctions were imposed before the new government had taken any significant action. To be sure, one can try to justify sanctions as essentially warning shots. But in Austria they appeared more like expressions of displeasure with Haider’s past pronouncements (on Hitler’s employment policies, for instance) than as principled objections to what the new government actually sought to do. This is a marked contrast with the cases of Hungary and Romania in particular: in both countries governments had a clear track record; what they were doing also had a systematically illiberal character and could not be excused as a one-off mistake.

Second, there is a crucial difference between Berlusconi’s Italy and the two states further east. True, the Cavaliere also tried to remove checks and balances and would have wanted to stay in power more or less permanently (and thereby also out of prison…). But the opposition, despite its generally sorry state, remained just about strong enough to resist a comprehensive refashioning of the political system; the media was in fact not completely dominated by Berlusconi’s own media empire; Berlusconi lost popular referenda, in particular one on constitutional changes in 2006; and, most important, the judiciary kept putting up a fight, while successive Italian presidents – perhaps most importantly Giorgio Napolitano – were willing to interfere with at least some of the Cavaliere’s plans. In short: there were reasonable grounds for thinking that the situation would over time self-correct through internal political (and legal) struggles. Here outside intervention could easily seem illegitimate: it could look like Brussels picking a winner in a domestic fight for power. All this of course amounts to nothing more than a point long familiar from John Stuart Mill’s writings in the middle of the nineteenth century: ideally peoples struggle for freedom and democracies (and preserve their democracies) themselves; as Mill put it: “the only test […] of a people’s having become fit for popular institutions is that they […] are willing to brave labour and danger for their liberation”.

Now, the responses fashioned to four eminently reasonable concerns also indirectly yield a set of criteria as to when there is a presumption in favour of EU interventions being legitimate. First, a member state government needs to have a track record of violating liberal-democratic principles. That track record should also show a government’s conduct to have a systematic character: one-off violations might be deeply problematic, but they should be seen in context. In other words, there is a place – in fact: a need – for political judgment here. Second, intervention is about enforcing commitments that were entered into voluntarily in the past. If there is reasonable hope that such commitments can mostly be enforced internally, intervention should wait. Third, there is no single, rigid template for understanding democracy in a European context. However, there are shared understandings that have evolved historically. Sudden departures from them put the burden of justification on the governments deciding in favour of such departures.

Something else, less tangible, matters, though: the tone and nuances of political language and leaders’ rhetoric. And this point goes both ways: on the one hand, criticism from the outside should never be suspect just because it comes from the outside – as I have been arguing, EU citizens share one political space and ought to make it their business what others in that space do. On the other hand, neither European politicians nor European intellectuals should generalize about, for instance, “the Hungarians”, as opposed to a particular government. Brussels should never treat member states as if they were like children who are a bit slow in getting liberal democracy: the EU as lived experience can be very different from the textbook account of “transitions to democracy”, where peace, prosperity and political happiness reign ever after.

The missing tool kit

Legitimacy and having appropriate policy instruments at hand is not the same thing. True, there is Article 7 of the Lisbon Treaty, which allows for the suspension of membership rights for states persistently violating basic European values. The idea for such an article had in fact been pushed by two paragons of Western European democracy, Italy and Austria, in the run-up to enlargement, out of fear what those uncouth eastern Europeans might do (the irony being that sanctions – though not under Article 7 – were of course first applied against Austria in 2000). But nowadays Article 7 is widely considered a “nuclear option”. In other words: it is deemed unusable. Countries seem simply too scared that sanctions might also be applied against them one day. In any case, the very idea of sanctions goes against what might be called a whole EU ethos of respectful compromise, mutual accommodation and deference towards national understandings of political values.

As an alternative to going “nuclear”, legal scholars have proposed that national courts, drawing on the jurisprudence of the European Court of Justice, should protect the fundamental European rights of member state nationals who, after all, also hold the status of EU citizens (something of which most Europeans are blissfully unaware, alas). As long as member state institutions can perform the function of guaranteeing what these scholars have called “the essence” of fundamental rights of EU citizens, as set out in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which protects EU citizens against abuses by EU institutions and which legal theorists consider in turn indispensable for European citizenship, there is no role for either national courts or the European Court in protecting the specific status of men and women as Union citizens. But if such institutions are hijacked by an illiberal government, Union citizens can turn to national courts and, ultimately, the European Court of Justice, to safeguard what the Court itself has called the “substance” of Union citizenship.

This is a clever thought: the aim is not merely to bring in the European Court, but to strengthen national liberal checks and balances in times of political crisis. Yet the thought is too clever by half in the eyes of observers who fear that the reasoning outlined above would open the door to a comprehensive review of all aspects of national legal systems by the European Court – thus upsetting the delicate balance between the Court and national constitutional courts and effectively making the EU into a federal state. Other critics hold that, even if this danger can be avoided, such a legalistic response to an essentially political challenge will not do.

But then what would a properly political response look like? It has often been said that the eurocrisis has brought about the politicization of Europe – and that it is now time for the Europeanization of politics: people have woken up to the fact that what happens elsewhere in Europe has a direct impact on their lives; Brussels is not just some technocratic machine which produces decisions best for all; what we need is a European party system, so that different options for Europe’s future can be debated across the continent. Did we not already see signs of such a truly democratic future when Orbán, in January 2012, appeared in the European Parliament and openly debated his government’s record?

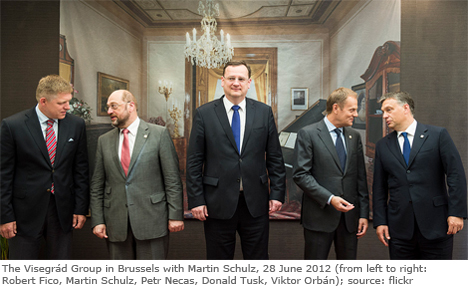

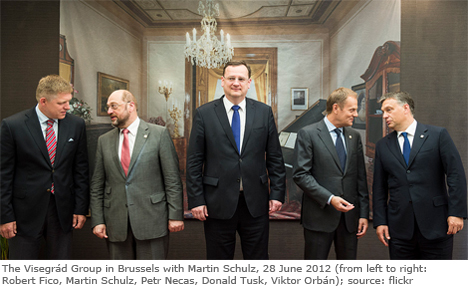

Alas, a less desirable effect of such a Europeanization of politics has now become apparent: the conservative European People’s Party firmly closed ranks around Orbán; on the other side of the political spectrum, Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament and one of Orbán’s most outspoken critics, has defended his fellow Social Democrat Ponta, at least initially. So it appears to be all party politics instead of an impartial protection of European standards.

Towards effective democracy-protection in the EU

How could the EU deal with challenges to liberal democracy more effectively? First of all, Article 7 ought to be left in place, but also ought to be extended. There might be situations where democracy is not just slowly undermined or partially dismantled – but where the entire edifice of democratic institutions is blown up, so to speak (think of a military coup). However, in such an extreme case, the Union ought actually to have the option of expelling a member state completely. As is well known, under the Lisbon Treaty states may decide to leave voluntarily – but there is no legal mechanism for actually removing a country from the Union (instead, there is only the possibility of suspending the membership rights of a country).

A difficulty with the existing harsher sanctions envisaged in Article 7 is, of course, that it requires agreement among all member states. So short of dramatic deteriorations in the rule of law and democracy, the EU ought to have tools available that exert pressure on member states, but whose employment does not require a lengthy process of finding agreement among all governments. One suggestion is that the Commission begins to monitor the state of the rule of law (essentially: the quality of the systems of justice) in all member states. It is important that such monitoring is done uniformly in all countries; while there are of course precedents in singling out individual countries for surveillance (Romania, Bulgaria), it simply sends the wrong signal – namely, one of prejudice and discrimination – to target only some countries.

However, one might question whether the Commission can really be a credible agent of legal-political judgment. To be sure, the Commission is acquiring new powers in supervising and potentially changing the budgets of eurozone member states. But many proposals to increase the legitimacy of the Commission (seen as a necessary complement to such newly acquired authority) contain the suggestion purposefully to politicize the Commission: ideas to elect the President directly or to make the Commissioners into a kind of politically uniform cabinet government all would render the body more partisan. And such partisanship makes the Commission much less credible as an agent of legal-political judgment.

An alternative to the Commission undertaking such a task itself would be to delegate it to another institution, such as the Fundamental Rights Agency, or perhaps yet another institution which could credibly act as a guardian of what one might call Europe’s acquis normatif. One could think of something like a “Copenhagen Commission”, as a reminder of the “Copenhagen criteria” to judge whether a country was democratic enough to begin the process of accession to the EU, and analogous to the Venice Commission, though with an even stronger emphasis on democracy and the overall quality of a political system – an agency, in other words, with a mandate to offer comprehensive and consistent political judgments.

However, the real question is of course: and then what? What if a country seems systematically to undermine the rule of law and restrict democracy? My suggestion is that an agency ought to be empowered to investigate the situation and then trigger a mechanism that sends a clear signal (not just words), but far short of the measures envisaged in Article 7. Following the advice of what I have termed the Copenhagen Commission, the European Commission should be required to cut subsidies for infrastructure projects (which make a significant difference in the poorer member states), for instance, or impose significant fines. Especially the former might prove to be effective, if the EU budget as such were to be significantly increased in future years (a measure also included in many proposals to tackle the eurocrisis).

At the same time, all the existing tools remain at the disposal of the relevant actors: member states could vote on Article 7; the Commission could take a member state to the European Court for infringement of the treaties; the Court could protect the substance of EU citizenship; and politicians could have a serious word with one of their peers in another member state, if they felt that the State in question is leaving the broad European road of liberal democracy.

None of this means that some of the pluralist principles and practices in the EU, which proponents of “diversity” as a major European value tend to laud, have become irrelevant (or were a fiction all along): all the main actors of democracy-defence can retain something like a margin of appreciation to account for national idiosyncrasies; they can in the first instance suggest to an offending government to take seriously the idea of informal peer review and try to negotiate disputes away, etc. However, it cannot be pluralism all the way down. As one political community, the EU has outer and inner boundaries: where liberal democracy and the rule of law cease to function, there Europe ends.