Consensus and controversy

Literature in a politicized age

In a politicized age, literary debate seems to be seeking consensus. But many still argue that the task of writers is to voice what would otherwise be seen as unacceptable. Today, the question is as much about how literature is talked about as what it talks about.

Much of the writing arriving on the scene today noticeably lacks the post-modernist suspicion towards reducing literature to ‘authorial intention’, a ‘message’, or a ‘theme’. Does this mean we are seeing a new littérature engagée? Or are our times so tumultuous that they demand a tumultuous literature?

In her book, The Balkans: From Geography to Phantasy (2013), the Croatian essayist Katarina Luketić warns that ‘every trauma is a spring, the more you repress it the stronger it comes back, each repression makes it more present, even though invisible, everything that gets thrown out through the window comes back through the door.’

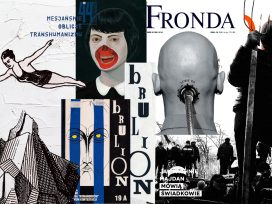

Over the last decade, we have often seen that the literary works which have been most discussed – which have become emblematic for a pressing problem – were not necessarily written with a progressive purpose. Often, they are agnostic, sceptical or cynical to the point of being seen as reactionary (the prime example is Michel Houellebecq, one of the few such authors to be received across Europe). Other writers and critics clearly endorse the idea of the existence of a ‘corridor of opinion’ – an åsiktskorridor in Swedish or a Gesinnungskorridor in German – where lines defining acceptable public speech are constantly drawn.

The explosiveness with which the decades-old controversy around Peter Handke resurfaced at the end of 2019 illustrated one thing very clearly: that a writer who even twenty years ago would have been viewed as ‘uncomfortable’, and for that reason worth reading, is today – in the age of the social media ‘shit storm’ – exposed to a rapid process of discrediting. Whether or not one considers Handke to have legitimated genocide or to be a torchbearer of poetic autonomy, the controversy said as much about how literature is talked about today as what it talks about.

Against the backdrop of the rise of the right, literary debate seems to be seeking consensus and a shared set of values. Others argue – citing political correctness or bourgeois hypocrisy – that the task of art and literature is precisely to voice what would otherwise be seen as unacceptable. Conversely, what was once subcultural playfulness or post-modernist experiment is gaining political momentum through internet-based rightwing movements. How to respond to claims of censorship, on the one hand, and the anti-liberal co-opting of emancipatory literary practices on the other?

According to Pascale Casanova, a ‘literary world’ or universe exists relatively independent of the everyday world and its political divisions, ‘whose boundaries and operational laws cannot be reduced to those of ordinary political space’. The literary greats, she argues, ‘have managed, by gradually detaching themselves from historical and literary forces, to invent their literary freedom, which is to say the conditions of the autonomy of their work.’ (The World Republic of Letters, 2007.)

Has literature become hostage to politics and ideology? Must it choose between artistic freedom and political engagement? If so, which side should it take? Are there writers today who whisper into the ears of populists or help them win support? What is the line between propaganda and literature? Is artistic autonomy possible at the current moment? Is the writer’s responsibility to art greater than her responsibility to her community? How does a writer navigate through these minefields?

The focal point ‘Consensus and controversy’ collects articles commissioned exclusively for Eurozine alongside contributions from Eurozine partners. It reflects the concern with literary subjects shared by the great majority of journals in the Eurozine network. The series is ongoing and will expand over the course of 2020 and beyond. We hope you find it thought-provoking!

The curators:

Miljenka Buljević (Booksa, Croatia)

Audun Lindholm (Vagant, Norway)

Simon Garnett (Eurozine)

Published 31 January 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.