The war for democracy

The governments now sanctioning Russian oligarchs forget to mention that it was the free-market policies of the ’90s that created them. In order to regain the initiative after misreading Russia’s aggression, the Left needs to point out how the war for democracy in Ukraine is part of its own struggle for global justice in the 21st century.

We really didn’t see this coming. Even when Russia’s mobilisation on Ukraine’s border had reached a level that made military invasion look inevitable, many of us didn’t actually believe it. Putin’s decision to invade still seems like a gross strategic misstep. Yet it has also been a reality check to us all.

In the weeks prior to the invasion, there was an eagerness in the West to take a ‘contrarian’ stance and consider Putin’s manoeuvres as a legitimate reaction to western security policies. Some of his apologists were motivated by pragmatic concerns, others were ideological. Many leftists stuck to the script that the US and NATO were the aggressors. They have had to realise in hindsight that by echoing the ‘spheres of influence’ doctrine and the narrative about justified security interests, they were serving as mouthpieces for Kremlin propaganda.

The Ukrainians themselves, roused by their spirited president Volodymyr Zelenskiy, can tell us what’s at stake now: this is a war waged by authoritarian forces to extinguish the flame of democracy. This war has been going on for many years, and not only in Ukraine. With Russia’s full-scale invasion, it has crossed the threshold from war to War.

The war for democracy is going to need the Left – its parties and unions, its publications and analysts. Urging to seek diplomatic avenues and avoid further escalation is still the right instinct, especially when faced with the risk of escalation going nuclear. But there are ways to enlist in the fight without abandoning an antiwar position.

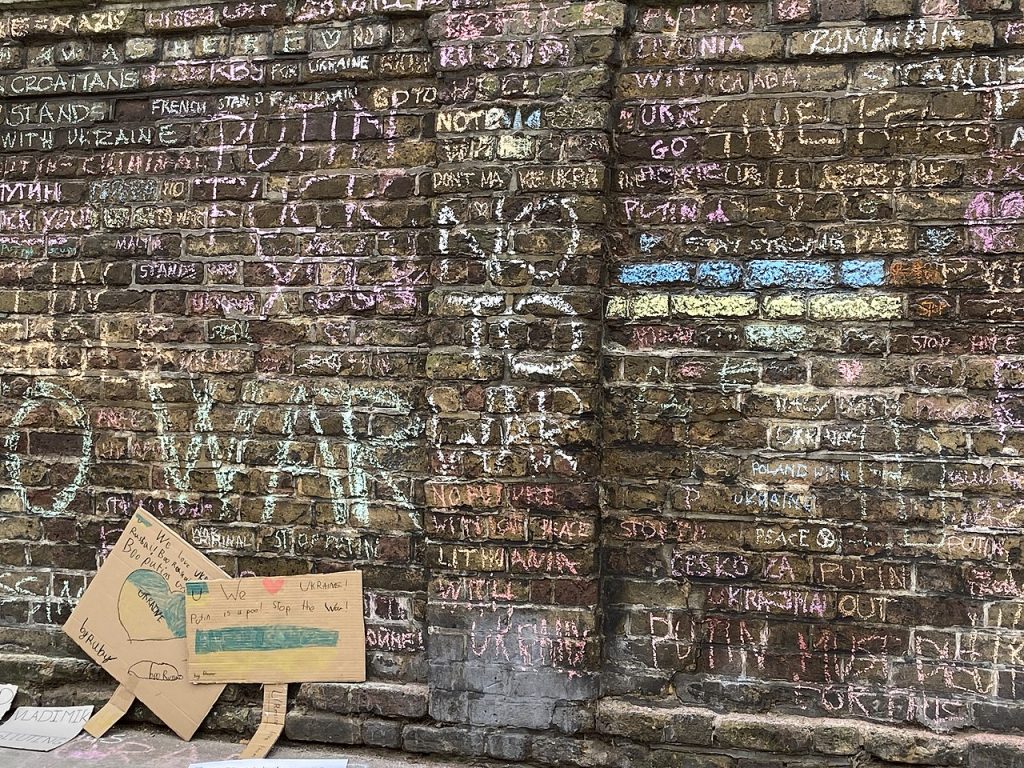

Graffiti on the wall of the Russian embassy in London, 28 Feb. 2022. Author: Matt Brown; source: Wikimedia Commons

The Left has now been handed an opportunity to recover from its initial embarrassment. Each day, unprecedented and exceptional policies are being improvised to hurt the Kremlin regime. France is seizing opulent villas and luxury yachts along its Riviera and its finance minister Bruno Le Maire has announced that a special task force is being set up to coordinate similar measures among the biggest western economies. The UK is making similar promises to crack down on the Russian wealth amassed in its midst, targeting the palatial assets that have earned the UK’s capital the nickname ‘Londongrad’.

These policies hardly seem characteristic of the governments who issue them. Granted, they’re exceptional measures issued in a state of emergency. But they’re a far cry from the neoliberal state of exception that ravaged Europe through the 2010s, with its austerity measures and technocratic coup d’états. Now we’re seeing something very different: conservative and centrist governments are setting a precedent for the criminalization of obscene wealth.

It is possible to seize the properties of the super-rich. At least this is the notion currently being planted in public perception. Suddenly, there’s talk of expropriated palaces being used to house Ukrainian refugees. This is an opportune moment for leftists to do some serious lobbying.

Let’s latch onto this and give credit to our governments for putting the war for democracy on the right course. But we should also remind them of what they tend to forget. That the emergence of Russian oligarchs happened on the back of the post-Soviet ‘shock therapy’ devised by Boris Yeltsin and his western advisers. London, Zurich and Cannes rolled out the red carpet for them. Our politicians cannot be allowed to forget that democracy requires the state to remain at the service of the people, instead of protecting the interests of the super-rich.

With the right emphasis, it’s possible to broaden the scope. Let’s map the environs of the Kremlin kleptocrats and go after their western business partners and associates, their lawyers and tax advisers, their estate agents, their loophole miners, everyone who has been making obscene profits from their dirty money schemes. We all know that this assault on democracy has been going on for a very long time. Let’s add the West’s own oligarchs to the list, and request that another task force is set up to bleed them dry.

Because this is a war for democracy, for its survival and its future shape and foundation. As the 2022 IPCC report made evidently clear, the war is intensifying on multiple fronts. Democratic governments must combat Putin’s belligerent regime and the impending catastrophe of climate change at the same time.

Fortunately, the battles overlap. Germany has finally waved farewell to Nord Stream 2 and ramped up efforts to decarbonise its energy mix, pledging an annual increase of solar and wind facilities with the aim of making the German economy 100 per cent dependent on renewable power by 2035. Good! But why not demand that investments in renewables match the 100 billion euros Olaf Scholz recently announced would be injected into Germany’s special rearmament fund?

Even if Putin were to be toppled, we can no longer assume that our way of life will be safely nestled in ‘western hegemony’. If we entertain the notion that we’re now living in a ‘multipolar’ world order, we should consider that the West, too, runs the risk of geopolitical isolation.

As Slavoj Zizek has suggested, it would be wise to strengthen ties with countries that the West used to treat as its colonies and imperial domains. Developing countries’ allegiance to the West cannot be taken for granted. It is high time to own up to the horrors inflicted on the Global South in the past by providing a political and financial commitment to its future.

In light of the flagrantly uneven impacts of global heating, it is the ethical thing to do. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine makes it seem no less right from a geopolitical point of view.

Published 21 March 2022

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Vagant © Eirik Høyer Leivestad / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

After six months of protests, there are grounds for hope that the tide is turning in favour of the Serbian student movement: first, the unification of the opposition around the movement’s demand for new elections; second, the emergence of a strategic alliance between the students and the EU.

Outrage and moral panic have become driving forces in global politics – but what role should emotions play in democratic governance? On the new episode of Standard Time, researchers examine the influence of moral emotions and their implications for political life.