Growing reluctance to engage with books is endangering democracy and science. Deep reading boosts the human capacity for abstract and analytical thinking, protecting us from the corrosive effects of bias, prejudice and conspiracy theories.

Like a prophet, Mahmoud Darwish is positioned between the tragic past of the Palestinian nakba, the present of occupation and exile, and hopes for a liberated future. Zeina G. Halabi places him in the context of the Arab enlightenment and the post-Arab Spring world to offer Palestinian liberation as a way of redeeming all humanity.

In ‘We, the Intellectuals’, Palestinian artist Oraib Toukan reflects on the complex relationship between intellectuals and the politics of cultural institutions in a post-Arab Spring world. She recounts a 1997 incident when Mahmoud Darwish read ‘In Ritsos’s Home’ to a packed auditorium at Amman’s Royal Cultural Centre. Upon reciting the verses ‘O Palestine/name of the earth/and name of the heavens/you shall prevail’, he was interrupted by a few zealous listeners, who chanted – perhaps not so spontaneously – ‘Long live His Majesty King Hussein the great!’

This explosive example of Jordanian authoritarian nationalism was nothing less than an orchestrated sabotage of Darwish’s verse, setting the power of the king against the poet’s prophecy of Palestinian liberation. Toukan recalls:

Darwish simply cleared his throat with a firm ‘ahem’ and moved on to his next verse. ‘In Pablo Neruda’s home, on the Pacific coast, I remembered Yannis Ritsos’, he read. ‘I said: What is poetry? He said: It’s that mysterious event, it’s that inexplicable longing that makes a thing into a spectre, and makes a spectre into a thing’.Flash-forward to now and a ‘Long Live the King’ interruption today would certainly cause a writer to pack up, leave, reject, refuse, and decline invitations from the institution thereafter. There are simply more cultural institutions to choose from – more thinkers, more artists, more spaces, more patrons, more of everything, really… Moral authority has been democratized. Anyone can speak truth to power; besides, power knows the truth.1

From the perspective of the Darwish-Ritsos exchange, Toukan is speaking from the future. We are in 2013, sixteen years after Darwish was hosted at the Royal Cultural Centre, and five years after his death; Toukan’s world abounds with bloody uprisings, military coups, and intellectuals associated with authoritarian regimes and institutions that construct truth as much as they disseminate it. In this sense intellectuals are ‘agents of regimes of truth’ and mediators of ideology and its social effects.2

Now that ‘moral authority has been democratized’ and everyone can protest against power, representation is no longer the prerogative of the ‘prophet-poet’. Darwish cannot claim to be the sole representative of Palestinian national liberation in Toukan’s contemporary moment. In Toukan’s ‘now’ – a present that is the future from the perspective of Ritsos’s and Darwish’s prophecy, when Palestine might have been expected to have prevailed – speaking truth to power is no longer prized as an act of courage. ‘Power’, as Foucault put it, ‘knows the truth’.3 In the Ritsos-Darwish future, power has heard it all before: it is unyielding, absorbs everything, and the intellectual is subdued.

In this short passage, Toukan captures a contemporary disenchantment in the wake of the intellectual’s prophecy has not come true. In the prophesized future, the intellectual-prophet cannot say anything new about prisons, poetry, and Palestine, for it has all been said already; the present shows us how the intellectual’s prophecy has become futile, replaceable, even redundant.4 No longer the lone voice speaking truth to power, the intellectual-prophet is, in Toukan’s tragic portrayal, stranded in a dystopian present, carrying the burden of his aborted prophecy, unable to move to the future.

Toukan’s sensibility stems from the cognitive dissonance of seeing the former power of the intellectual’s prophecy and tracing its demise. It begins by discerning, as anthropologist David Scott puts it, ‘the temporal disjunctures involved in living on in the wake of past political time, amid the ruins, specifically, of post-socialist and postcolonial futures past’.5 The entwinement of the prophetic past, dystopic present, and stalled future are temporalities that remind us of the intellectual’s interrupted journey toward emancipation.

Oraib Toukan’s layered depiction of Darwish, first as Ritsos’s prophetic interlocutor, and later as an interrupted poet, evokes a discursive dissent in post-1990s Arabic literature depicting intellectuals.6 Mahmoud Darwish evoked the Arab intellectual-prophet all too well; but in what constitutes the poet’s prophecy?

Simone Bitton opens her documentary Mahmoud Darwish: As the Land is the Language (1997) with a long drive through a desert road. A man is captured in high angle as he contemplates the overwhelmingly barren landscape. The narrator wonders:

How to film exile? A Palestinian poet looks out over his homeland from the slopes of Mount Nebo, on the eastern bank of the Dead Sea and the River Jordan. It was from here that Moses is supposed to have contemplated the Promised Land, which he was never to enter. Palestine is just across the river; so near, yet so far.7

From the outset, Bitton is consumed by the same fascination with exile that accompanied Darwish in his work, sharing his anxiety about representing exile. But, although Bitton broaches the different significations of ‘exile’ in the documentary, she treats it as a state of transcendental and allegorical displacement.

Mahmoud Darwish standing on Mount Nebo in Jordan overlooking the West Bank in Simone Bitton’s documentary ‘Mahmoud Darwish: As the Land is the Language’ (1997). Courtesy of Simone Bitton.

Bitton opens her first scene at the ‘original’ moment of exile at Mount Nebo, where Moses stood looking over the Promised Land for the first time. The Biblical motifs of the desert, Mount Nebo, and River Jordan are rendered in a wide-angle shot recalling the divine gaze looking down, not without sympathy, at the tragedy of the exiled people. As in the scriptures, the Prophet speaks Truth in the name of his wandering people and shall lead them to the Promised Land. The scene shows us the Palestinian question from a viewpoint that transcends earthly exile and entrusts it to the poet-prophet who does the work of Moses. Bitton, however, sabotages the narrative of Zionism, for the land in question is not Israel but Palestine; the ‘chosen people’ are not the Jews but the Palestinians; the messenger of truth is not a prophet, but a poet; indeed, the prophet is not Moses, but Mahmoud Darwish.

This dialectical reconstruction of exile is one of the most revealing portraits of Darwish. Invoking his poetry’s prophetic iconography, it evokes displacement, absence, and the privilege of representation, about who speaks for the wandering people and how. It asks the question of how exile is framed temporally, probing the conceptions of time at work in this experience. Palestine is thus revealed across three successive temporalities: historically embedded in Biblical tradition and collective memory; a signifier in the present of displacement and loss; and projected into the future by the spectral figure of the exiled poet-prophet. The scene is thus about the intertwinement of the lyrical and the political, the personal and the collective, and the spectral and messianic; all set the parameters of the intellectual-prophet.

This is where the enmeshment of the poet-prophet, Palestine, and manifold temporalities turn into a metanarrative. We watch Bitton representing Darwish; he represents the Palestinians in 1997 from the vantage point of today’s coups, revolutions, and civil wars, all of which have had an effect on the conception of the ‘prophetic intellectual’. The visual and allegorical incongruity between Oraib Toukan’s and Simone Bitton’s depictions gives the figure of the intellectual-prophet aesthetic and epistemic sense. What is at the core of the intellectuals’ prophecy? How do they articulate it? And in whose name? Here again, I turn to Darwish as the quintessential poet-prophet who reflected on and simultaneously embodied these questions.

Mahmoud Darwish’s project was one of national emancipation, but he also had a humanist, universal outlook on alienation, displacement, and exile; he spoke of to transcend merely local, specific questions and engage instead with a poetics of the absolute. He wanted to ‘inscribe the national on the universal’, he says, ‘so that Palestine does not limit itself to Palestine, but that it may found its aesthetic legitimacy in a vaster human space’8. Darwish universalized the particular by making the Palestinian question legible as a human narrative of displacement, while particularizing the universal by showing how we can read a universal story about human emancipation as such in the Palestinian tragedy. As such, Darwish, like many of his generation, owed much to the legacy of the nineteenth century Arab Enlightenment, the nahda.

This invited Arab intellectuals to selectively reconcile Western epistemology, science, and politics with the tradition of Arab and Islamic thought. Humanism permeates these teleological narratives; the subject is conceived as the master of a world that ushers in freedom and promises emancipation. Endowed with a universal ethos and identifying themselves as ‘modern’, nahda intellectuals laid the contours of the emerging Arab subject.9

The modern Arabic literary canon has thus channelled writers’ aspirations and anxieties as they navigated their troubled path toward modernization. Arab writers narrated the push and pull between tradition and modernity, East and West nexus, and coercive powers both domestic and foreign, within secular-nationalist frameworks with different conceptions of the ‘political’. The anti-colonial, pro-Palestinian, and pan-Arab revolutionary discourse that laid out a future of possibilities persisted throughout the 1960s.

Mahmoud Darwish stencil tag in downtown Tunis, photographed in 2017. From Wikimedia commons.

Despite the overwhelming sense of defeat following the Six Day War against Israel, the figure of the intellectual remained a powerful reminder of the word/praxis model. The intellectual re-emerged, from Ghassan Kanafani’s conception of ‘resistance literature’ to Elias Khoury’s codification of the writer as an allegory of the nation in crisis. Perhaps the intellectual became even more urgent in the wake of setbacks, beginning with the collapse of the United Arab Republic and not ending with the Lebanese Civil War. These historical junctures turned the critical focus from imperialism and class struggle to culture, exemplified by the resilience of sectarianism.

Navigating the rough road of decolonization on the one hand and the power of endogenous structures of oppression on the other, politically committed writers turned to language and thought, confronting the impending danger of erasure of selfhood by ‘forging a historic possibility’10, as Edward W. Said wrote. In a context of crises and the systematic erasure of peoples and memories, the role of Arab writers was, according to Said, ‘to be one of making the present in such a way as, once again, to make it in touch with past authenticity and future possibility’11 Put differently, the word and the text were indiscernible from the prophecy in which the intellectual projects Arabs into the future. In the mission to create an Arab present that ushers in a future of possibilities, the Arab intellectual continued to speak, as Foucault wrote, ‘the truth to those who had yet to see it, in the name of those who were forbidden to speak the truth: he was conscience, consciousness, and eloquence’12

Resistant to the seductions of power, the intellectual embodies a spirit that speaks in the name of the marginalized and the disenfranchised, disturbing the status quo, and challenging institutional power in all ways possible by making connections that are otherwise silenced and denied.13Darwish, again, illustrates this.

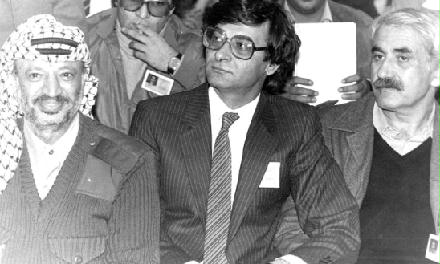

After the establishment of the Palestinian Authority and the initiation of the process of state-building in the West Bank and Gaza, Yasser Arafat reinvented himself from the leader of guerrilla warfare to the president of a semi-autonomous fragmented political entity. It was imperative that the most prominent Palestinian intellectual participated in that transition to give it legitimacy. Darwish recounts to Simone Bitton how he rejected Arafat’s offer to join his cabinet:

He asked me ‘What harm did it do when Malraux became a Minister in De Gaulle’s cabinet?’ I said there are at least three differences: First, France is not the West Bank and Gaza. Second, the circumstances of Charles De Gaulle are not those of Yasser Arafat. And third, André Malraux is not Mahmoud Darwish … negligible differences. But if Palestine were to become a great state like France, and Yasser Arafat were to have Charles De Gaulle’s power, and I were to reach Malraux’s stature, then I would rather be Jean-Paul Sartre.

Here, the intellectual conveys his ambivalence about Arafat’s authority and autonomy by subverting the Malraux comparison as an endorsement of political power. Only when Palestine is autonomous, and Arafat as uncompromising as De Gaulle, will the intellectual consider reconciling themselves with power. Even then, however, the model Darwish admires is not Malraux, but Sartre; Darwish reminds Arafat and subsequently his audience that, as Minister of Cultural Affairs during the uprising of May 1968, Malraux was on the other side of political power, not alongside but facing Sartre, the visionary of political commitment, the anti-colonial intellectual leading the protests. The intellectual that Mahmoud Darwish has in mind is more akin to his friend and interlocutor Edward Said, one who relishes critical distance from power despite, or perhaps because of, his unrivalled cultural and symbolic capital.

Mahmoud Darwish photographed in the company of Yasser Arafat and Geroge Habash in 1980 in Syria. From Wikimedia Commons.

The Arab Enlightenment mission was predicated on the intellectuals’ ability to represent a community in a moment of transformation Speaking in the name of a silent and silenced other is intimately linked to authority, the question of who is entrusted with the prophecy or entitled to create a field of meaning for others and speak in their name. In that sense, the intellectual is an individual, as Said imagined him, ‘endowed with a faculty for representing, embodying, articulating a message, a view, an attitude, philosophy or opinion to, as well as for, a public’14. The faculty of representation, of speaking in the name of absolute values, and promising victory for the sake of the disenfranchised, is a critical constituent of Darwish’s intellectual prophecy. His legitimacy as the intellectual-prophet stems precisely from his power to represent, enlighten, and lead the voiceless.

By 1970, Darwish had become ‘the poet of the [Palestinian] Resistance’. Following the publication of four influential poetry collections, his name became the signifier of both Palestinian nationalism and poetry.15 As such, the intellectual’s word is endowed with the power of achieving collective salvation, to represent the plight of the silenced and the marginal, particularly during moments of national crisis. Darwish demonstrates the representative powers of the prophecy, yet again.

In February 1983, Darwish stood on a podium in a crowded hall in Algiers before Arafat, the Chairman of the Palestinian Liberation Organization and hundreds of Palestinian leaders representing different political factions. A few months earlier, in summer 1982, Lebanon had witnessed one of the worst episodes of its Civil War. The Israeli siege of Beirut ultimately led to the fall of the city and the withdrawal of thousands of Palestinian freedom fighters, Fida’is, to the sea, and eventually Tunisia, where the PLO relocated. Left on their own and without protection from local and regional allied forces, thousands of the remaining Palestinian refugees of Sabra and Shatila camps were massacred by Lebanese Phalangist militias.

The tragedy of 1982 engendered multiple experiences of loss: Beirut, the city that had sheltered the Palestinian resistance; vulnerable refugees and heroic Fida’is; Arab solidarity with the Palestinians. Displaced again, Palestinian refugees were left powerless but for the word of their poet-prophet. In a dramatic moment exuding resentment, pride, and grief and verging on sacrilege, Darwish read – rather, recited– an epic poem about the 1982 siege of Beirut. ‘Praise of the Tall Shadow’ (Madih al-Zill al-ʿAli, 1983), captures the tragedy of the capitulation of the Fida’isand the horror of the camp massacres. Drawing on perennial poetic genres – from boast, panegyric, and invective to elegy – Darwish poetically reconstructs the dramatic fall of the Fida’is in an auditorium in Algiers, packed with Fida’is, leaders of the PLO, and allies of the Palestinian liberation struggle, Darwish stands on the podium and gestures to the Qurʾanic verse, ‘The Blood Clot’:16

Recite:

In the name of thy Fida’i who created, [applause]

created horizon of a boot. [applause]

In the name of thy Fida’i who renounces

Their world

To His first calling,

The very first.

…

In the name of thy Fida’i who begins

Recite!

The reading ends with a standing ovation. Arafat walks toward Darwish and embraces him as numerous cameras capture the moment when leaders of the PLO bury their differences and unite around the indisputable representative of the Palestinian people in exile. As he speaks in the name of the Fida’i-God (‘In the name of thy Fida’i’), as Muslims invoke God in prayer (‘In the name of God’) and prostrate themselves before his might, Darwish reiterates his own power as the poet-prophet yet again. As he deifies the Fida’i, he consecrates himself as the prophet entrusted to carry the Fida’i’s word and lead his people through exile. By enacting this role, Darwish uses the word and the verse to mediate the ethos of emancipation. Darwish here gestures to Sartre’s conception of the politically-committed writer and yet transcends him by pointing to the emancipatory potential of poetry. He uses verse to speak in the name of the Fida’i, for the exiled Palestinian people, and to Israel and Arab regimes of oppression. He speaks not only truth but also liberation to power.

This is how the intellectual’s prophecy is embedded in a theological iconography. It draws on the topos of the exilic prophecy, of theologically coded spaces (e.g. Mount Nebo), whose sense of spectral timelessness is only enhanced by its displacement, and the centrality of the prophetic word in a teleological discourse of salvation. The self-fashioning and depiction of the intellectual evoke all these Biblical signifiers, yet they do not relinquish the worldly and the secular.

This multi-layered portrait of Darwish lets us understand the intellectual-prophet as the embodiment of Enlightenment values. This intellectual uses the power of the word not only to speak truth but to advocate emancipation. The intellectual’s legitimacy stems precisely from his distance from structural power. He represents the disenfranchised, which lay at the fringe of power by means of the word. The intellectual thus carries a communal history, beset by a tragic present, which he sees unfolding into a promising future.

Mahmoud Darwish is the emblematic figure of the modern Arab intellectual, though not without ambivalence. As the poet-prophet standing on the allegorical Mount Nebo, this figure is prophetic, representative, and righteous. The poet-prophet is a modern force and a force of modernity, an intellectual who secularizes the divine by means of his omnipotence, his unmatched ability to lead change; he is omniscient and, most importantly, endowed with the insurmountable power of omnipresence because he is spectral, identifying with and embodying that which constitutes the Arab experience of modernity and continuing to hover over an uncertain future. The contemporary, the moment in which this all happens, is the aftermath of the prophecy, where the intellectual is interrupted by coercive forces that leave him silent; where power is unyielding and the intellectual, subdued.

Darwish and his poetry are the inexplicable spectral prophecies hovering over Toukan’s text, just as Ritsos hovered over Darwish’s poem in 1997. In Toukan’s description of the Amman poetry reading, Darwish appears as a remainder of his past self, encapsulating the aspirations, contradictions, and predicament of the Arab intellectual-prophet. In this context of disenchantment, what remains of the Arab intellectual’s prophecy?

The view from Mount Nebo in Jordan, photographed by Faris Knight. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Toukan’s depiction of Darwish, first as Ritsos’s prophetic interlocutor and later as an interrupted speaker, evokes a discursive dissent characteristic of post-1990s Arabic literature about intellectuals. Although identifying with different historical generations and espousing distinct aesthetic sensibilities, contemporary writers dialectically appropriate the archetype of the Arab intellectual-prophet by retrieving their 19thcentury Arab Enlightenment forebears like Jurji Zaidan, and Palestinian intellectuals like Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Edward Said, and Mahmoud Darwish. Contemporary writers simultaneously elevate the figure of the prophetic, nationalist, exiled intellectuals and point to its faltering power. As they embrace a self-reflexive, non-secular, affective mode of criticism, contemporary writers reject the ideologically codified objectification of the intellectual and, ultimately, question the viability of the modernist principles of the construction of this archetype.

In fictionalizing and then burning an effigy of the modern, secular, nationalist, and exilic intellectual, contemporary writers create a critical counter-discourse that questions intellectuals as the producers and disseminators of knowledge. Notions pertaining to the intellectual-prophet as a modernizing subject, political commitment as a literary ethos, exile as a catalyst for change, and secular nationalism as ideologies of emancipation have lost their critical vigour and become symptomatic of a defunct political discourse and, in turn, the locus of dissent. Espousing a distinct conception of what constitutes the political, contemporary authors have relocated their critique from an explicitly logocentric, teleological, and secular-nationalist discourse to one that is anachronistic, transnational, non-secular, and latently affective, predicating the political on the personal. It is significant inasmuch as it invites us to theorize that which we call ‘the contemporary’.

Oraib Toukan, “‘We, the Intellectuals’: Re-Routing Institutional Critique.” Ibraaz: Contemporary Visual Culture in North Africa and the Middle East. Accessed June 20, 2015. http://www.ibraaz.org/essays/98#_ftnref24.

Michel Foucault, 'The Political Function of the Intellectual', Radical Philosophy 17/13 (1977), 207.

Toukan, ‘“We, the Intellectuals”’.

Ibid.

David Scott, Omens of Adversity: Tragedy, Time, Memory, Justice, Duke University Press, 2014, 2.

Sections of this article have originally appeared in Zeina G. Halabi, The Unmaking of the Arab Intellectual: Prophecy, Exile, and the Nation, Edinburgh University Press, 2017.

My translation from the original Arabic. Simone Bitton, Mahmoud Darwish: As the Land is the Language, Arab Film Distribution, 1997.

Mahmoud Darwish, 'Mahmoud Darwish', trans. by Pierre Joris, Boundary 2 26/1 (1999), 81.

Jean-François Lyotard, 'The Wall, the Gulf, and the Sun: A Fable', in Political Writings, trans. by Bill Readings and Kevin Paul Geiman, University of Minnesota Press, 1993, 3.

Edward W. Said, 'Arabic Prose and Prose Fiction after 1948', in Reflections on Exile and Other Essays, Harvard University Press, 2000, 64.

Ibid., 49.

Michel Foucault, 'Intellectuals and Power', in Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. by Donald F. Bouchard. Cornell University Press, 1980, 207.

Ibid., x

Edward W. Said, Representations of the Intellectual: The 1993 Reith Lectures, Vintage, 1996, 11.

Faysal Darraj, 'Transfigurations in the Image of Palestine in the Poetry of Mahmoud Darwish', in Mahmoud Darwish, Exile’s Poet: Critical Essays, edited by Hala Khamis Nassar and Najat Rahman. Northampton, MA: Interlink Books, 2008: 58.

‘Recite: In the Name of thy Lord who created, created Man of a blood clot’ (Quran 96:1–2).

Published 27 December 2019

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Zeina G. Halabi / Eurozine © Zeina G. Halabi / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Growing reluctance to engage with books is endangering democracy and science. Deep reading boosts the human capacity for abstract and analytical thinking, protecting us from the corrosive effects of bias, prejudice and conspiracy theories.

In rekto:verso: what the body of the action hero says about relations of power; why yoga’s discourse of accessibility rings hollow; and whether fitness practitioners should really be reading Mishima.