Photo by Carl Jorgensen on Unsplash

15 June, while waiting about in a church hall

This summer, I am going to compose an essay about poetry. For weeks now, a little pile of new books has been going everywhere with me, all packed tightly together in my bag. They’ve travelled many miles to many interesting places – all round England, Wales and Scotland. The aim, of course, is to read them. And thoroughly, in an orderly fashion, from cover to cover, starting at the start and ending at the end, whilst making notes and underlining all the metaphors and similes and labelling them carefully with tiny arrows and numbering them (it’s not for nothing I’ve spent the last twenty years and more in colleges, oh no). One day, out of the blue, a vista of hours will open up in front of me like a boundless horizon. Then, I’ll proceed as above, do the poems justice and compose my essay. And, then, I’ll spend more hours polishing it. In the meantime, I carry the books around with me everywhere, every day, just in case that moment should arrive, so I don’t miss it.

But there are tickets to buy and planes and trains departing to all destinations. Essays to read and marks to add up. Potatoes and carrots to peel. Emails to dispatch to Berlin and Bangor. And serious time is needed, every now and again, for dillydallying and staring holes into the air. An unwritten poem is tugging impatiently at the hem of my coat, like a child, all wide-eyed and piteous. Committees. A lecturer from America to introduce, oh my word, tomorrow (how did that happen?). And the world’s most adorable children have just turned up on my doorstep, in their finest fancy dress, and they all want to go to the funfair. I have to think about Walter Benjamin, and remember about the raffle and go to the post office. Put a book to bed. Put a child to bed. Make more space for doubt and irony. Read about colonies near and far, within and without. Sign this, say that. A real-life child is tugging at the hem of my coat, like an exciting new poem. This child, it must be said, doesn’t look particularly piteous, but he reminds me all the same that he too, and not unreasonably, requires some kind of upbringing. Birthdays. A dance. Video art, artists from overseas. Both ends of the candle to burn.

I wouldn’t change any of it. But when will that moment and that endless vista of hours come, so I can read these new books from cover to cover in an orderly fashion and compose a profound and significant essay about them? The phone’s twittering. The child.

16 June, off and on, in between this and that

In the meantime, I’m reading in a different way: at the hairdressers, in the half-dark before the house wakes up, on my way from A to B to C via Z, waiting for the bus, here and there, now and then, in bursts of five and ten minutes, palming handfuls of seconds, upcycling time, without a plan and with nothing to make notes on. And while doing this on Saturday morning, waiting in a church hall for the child’s drama class to finish, I suddenly recall something I had read in a book long ago.

The book is the great 1974 novel Leben und Abenteuer der Trobadora Beatriz nach Zeugnissen inrer Spielfrau Laura: Roman in dreizehn Buchern und sieben Intermezzos (The Life and Adventures of Trobadora Beatrice as Chronicled by her Minstrel Laura: A Novel in Thirteen Books and Seven Intermezzos) by the late East German author Irmtraud Morgner. This experimental and audacious work – the best novel ever, I have sometimes thought; everyone should read it – is often described as magic realism. But the very general term barely captures the book’s energy and originality. Indeed, its very title heralds resistance to any kind of conventional categorization. The Trobadora’s tales contain a host of characters and events weaving in and out of a micro-chapter and short text assemblage, a montage of notes, diary entries, old and new legends, socialist realism, poems, playlets and a wealth of other entertaining yet serious forms.

Little by little, the principle behind this montage begins to emerge as one of the protagonists, Laura Salman, the volume’s supposed, fictional editor, develops a practical literary theory to explain it to a prospective publisher. According to Laura, this is the ‘operative montage novel’ and ‘the novel form of the future’. For one thing, she says, it provides true expression for a modernity unsuited to the traditional novel’s awkward, slow structure, which is ‘possible nowadays only for lethargic or stubborn characters’. And, for another, Laura is busy. Inter alia, this former academic is a trolley-car driver, mother to a small boy, minstrel, lover, wife and citizen, multitasking to the max and ceaselessly. Laura can only write in stolen instants here and there, at full tilt and under pressure. She compares this activity to the release of compressed air in brief bursts of intense, explosive energy.

Photo by distelAPPArath from Pixabay

Such explosive writing flashes into my mind as I dash to collect the child, still clutching my book of poems. Nowadays, distant as we are from the German Democratic Republic of yore, different as my far easier life is from Laura Salman’s (though I’d quite like to drive a trolley-car), we still need to embrace top-speed reading. I can’t be the only person whose attention is pushed and pulled to distraction.

17 June, in the middle of the night

Apart from the applied montage novel, there are few forms better suited to such high intensity, interval reading than the short poem. Open a book of poems at random and there’s a prize every time. Any page will hold something new and shiny: long, short, rhyming, free; violence, love, loss. A poem can light up in the space of a moment, like a meteor, like those other forms which catch our eye now: text messages, tweets. Is there any more modern writing than a poem and its demand for modern ways of reading?

25 June, in the morning (everyone’s gone out already; I should be in the office or in the library, labelling metaphors and similes)

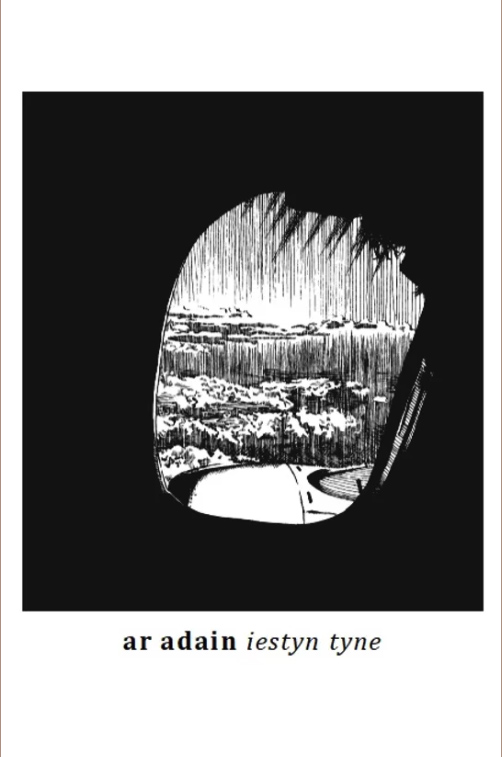

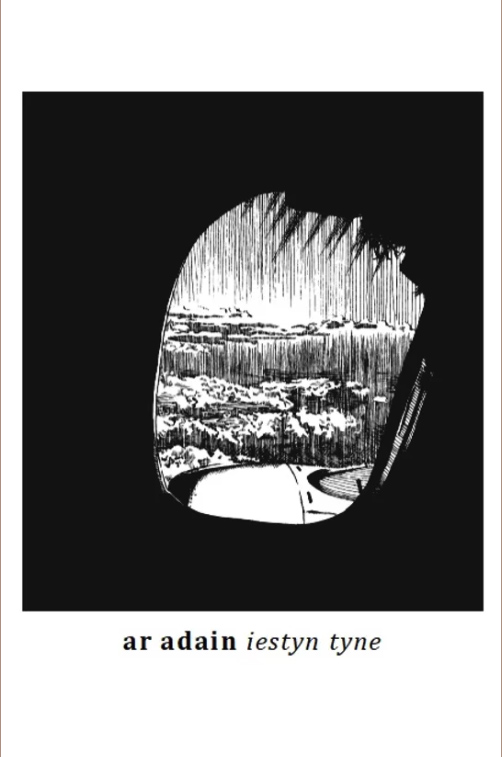

Sitting in the church hall, I have a new book in my hand – Ar Adain (On the Wing). This is the second poetry collection by Iestyn Tyne, a young poet from the Llŷn peninsula in northwest Wales. It contains twenty-nine poems, most, but not all, in free verse, not to mention a series of the poet’s own drawings, facsimiles of diary or notebook entries and other miscellaneous pages. From the start, this volume announces a consistent vision and conscious architecture. It opens with a poem entitled Cyrraedd Aber (Arriving at Aber) – that is, the university town Aberystwyth – and ends with Gadael Aber (Leaving Aber). This bracketing suggests that the poems record one short period, an academic year perhaps, one which is, as the title implies, criss-crossed with journeys. Indeed, this volume is, above all, a travelogue of journeys around Llŷn, the Basque country, Ireland and Wales, many of them bearing a note of time and place. The volume is also held together by further thematic networks: travel, nature, sickness and death, landscape and love.

Book cover of ‘Ar Adain’ by Iestyn Tyne via ystamp.cymru

25 June, late evening, off and on (it’s a hot night and the child is restless)

In a word, this is a tightly woven fabric. A short preface draws our attention to the anchoring thread that runs through not only this volume but also the poet’s other work: ‘Erchwyn gwely, ymyl llafn, clogwyn uwch y môr … y mae yn y llefydd hyn, ac ym mhob erchwyn ac ymyl arall, ryfeddod’ / ‘A bedside, a blade’s edge, a cliff above the sea … these places, and all other edges and limits, hold wonders’. Cyrraedd Aber presents this theme almost programmatically as it registers the seaside, a car park, some chapel steps, a doorway, a pavement and waiting somewhere between bed and kitchen for someone who isn’t yet there – all liminal points. Throughout the collection, reference is also frequently made to other boundaries and borders: windows, mountaintops, hilltops, a graveside, daybreak, a break-up, a bridge, Llanddwyn Island. Here, the edge is excitement. At the end of the poem on Gleann Cholm Cille, on Ireland’s Atlantic coast, we read: ‘This is the west of all our wests / we dance its limits’.

These are not places and instants in which to linger, for they are by their very nature transient. Striking, too, is the insistent reference to movement and motion: on foot, in cars, a plane, a ship. The volume’s interest in temporary situations is also underlined by the dates that sign off many of the poems and so mark their limits in time. Yet this vision is not a nostalgic one, because a date is an index of sequence as much as it is of finitude. It tells us, as sure as tomorrow is tomorrow, that there’s something else to come. Thus, the volume takes decisive leave from bleaker traditions that link the evanescent with loss. Here, something lost makes way for something new, right here and right now.

Thus, Ar Adain is remarkably optimistic, even at its darker reaches. The poem Cerdded Rhaff (Tightrope) describes someone in a deadly storm walking ‘rheffyn o ffin frau sy’n / llosgi dy draed / gam i ffwrdd o’r dibyn’ / ‘a fragile border like a rope which / burns your feet / one step from the edge’. This isn’t a literal cliff-edge; rather, the poem makes reference to meddwl.org, a website which offers mental health advice in Welsh. So if this scene is fraught with danger, it is framed too by faith in ‘dwylo yma’n / estyn amdanat’ / ‘hands, here / reaching for you’. Galwad (A Call) evokes an ageing character, again at a cliff top. Of course, this isn’t (only?) a real cliff. And yet, even in extremis, the poem describes not death but ‘troedio’r dibyn / rhwng cerdded a hedfan’ / ‘treading the edge / between walking and flying’.

Aberystwyth Jetty

Photo by Jynto from Wikimedia Commons

Jynto / CC BY

26 June, morning (everyone’s still milling about in the house, saying goodbye)

At first sight, this thematic consistency seems to suggest reading Ar Adain systematically, to see how its narratives develop. But there are other ways of reading it, ways which resonate with its engagements with borders, the fleeting, the fluid.

This book is smaller than an e-reader, small enough to put in your pocket, to go on the road. Yet some of its pages even contain more than one poem. Only one, Gweld (Seeing), extends over more than one page (not that it’s too long in its exploration of time dragging on after a painful parting, it just needs a certain scope to evoke that state). But the other, very short poems recall the other communicative forms which feature again and again in this poet’s work: phone calls, text messages, postcards, a rapid sketch, perhaps on a paper tablecloth, a notebook page.

These are poems not only for the library and endless hours but for the station platform or in between two bus stops. And, if you look more closely, you’ll see that they don’t appear in the order in which they’re dated (those of us who write annotations and draw little arrows on poems like to notice such things). Some dates fall before that of the opening poem and, come to think of it, the closing piece isn’t dated at all. Who then knows the date of that departure? Perhaps it is yet to come? So the initial impression of a straightforward timeline is deceptive, for it seems that the poems simultaneously fall outside the world of clocks and calendars, and that their journey’s end is unknown. They invite us, then, to read haphazardly.

24 June, evening

We may believe, today, that the best way to read and write is with patience and order. One day, I think, we’ll believe in the opposite, in explosive reading and writing.