There is nothing ‘natural’ about the coronavirus pandemic: global capitalism has created it. Containment measures of social distancing bear the characteristics of a general strike. It can serve as an experiment taking back control over our own time, Bram Ieven and Jan Overwijk argue.

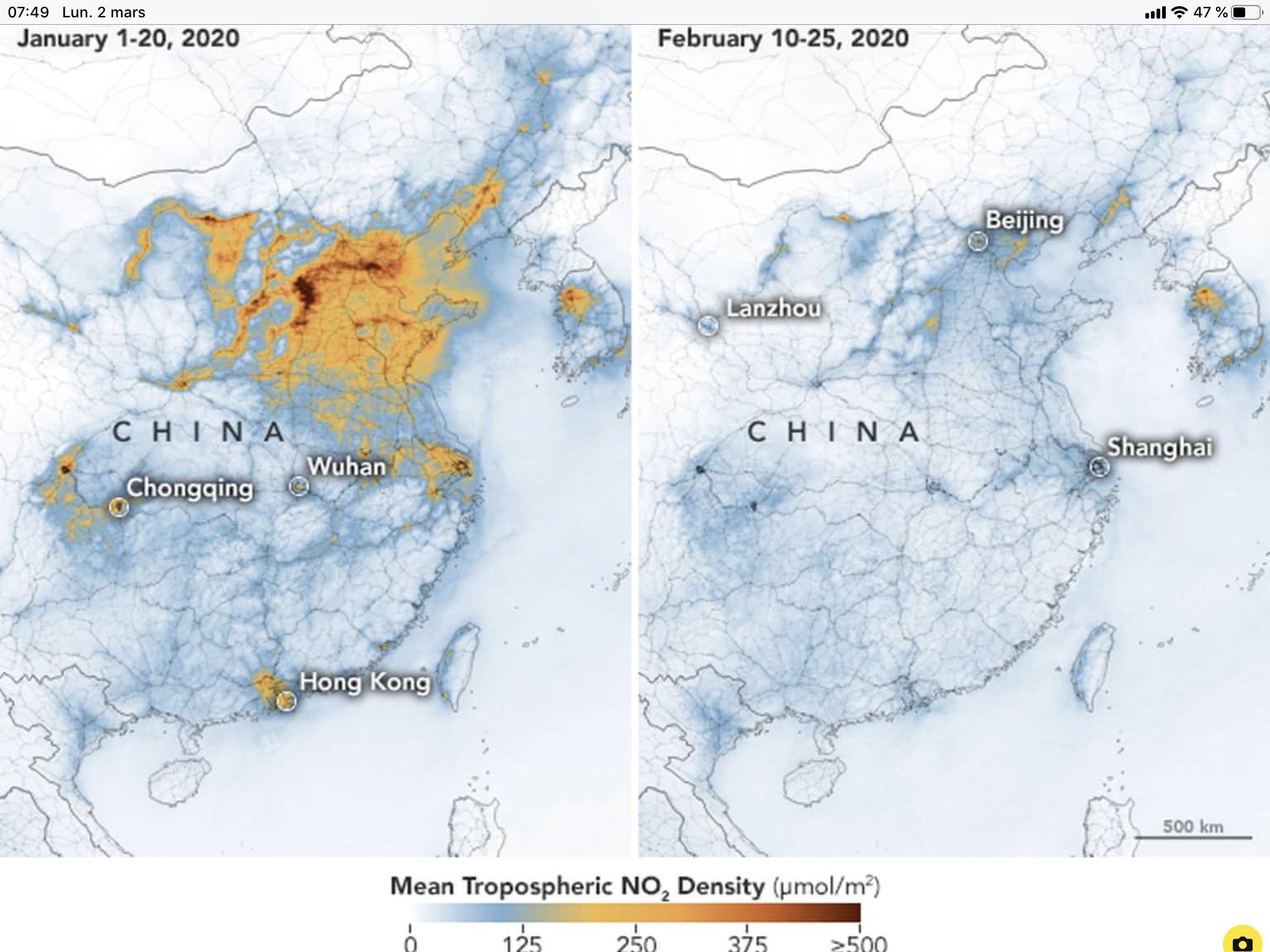

Two areal maps of China. The map on the left, from early January 2020, shows how orange-coloured nitrogen clouds extend over the entire country. On the map on the right, from a month and a half later, those same clouds have disappeared. What happened?

Via Twitter.

It was French philosopher Bruno Latour who shared these satellite images in a tweet, pointing out that a virus was able to achieve political measures that the Chinese state had always believed to be impossible. For the map on the right shows China after its intensive internal traffic came to a halt, just a few weeks after the quarantine was put in place to contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bruno Latour has been advocating a reconceptualization of how we think about modern politics for decades. Instead of thinking of our political order as clearly distinct from nature, in We have never been modern (1993) Latour suggests that the political is always interwoven with the natural order from which it claims to distinguish itself. The COVID-19 pandemic proves his point once again. However one imagines how nature and culture are interconnected, it is clear that ecological agents have a powerful bearing on society. The COVID-19 pandemic forces us to push this idea even further: it is time to face the fact that our political system itself has played a major role in producing this new ecological actor. We are the ones creating this so-called monster.

Not natural

In a global economy that increasingly intervenes in the ecosystem, it is not surprising that new viruses emerge and then migrate from one side of the world to the other at lightning speed. There is nothing at all ‘natural’ about that. The speed at which the virus is spreading is driven by economic globalization, and the asymmetry by which it does is guided by socio-economic inequality. It also applies to the way viruses such as COVID-19 enter our society.

The first thing to understand, as head of the Global Virome Project Dennis Caroll recently suggested, is that when it comes to these kind of viruses, ‘whatever future threats we’re going to face already exist; they are currently circulating in wildlife.’ In recent years, we have seen the demand for wildlife on the food market rise. With this marketization of wildlife, we are getting in closer contact with millennia-old ecosystems that were previously closed off from interaction with humans. On the basis of that argument, biologist Rob Wallace, author of Big Farms Make Big Flu, concludes in a recent interview that by way of deforestation and through the marketization of wildlife ‘many of those new pathogens previously held in check by long-evolved forest ecologies are being sprung free, threatening the whole world.’

It is this catastrophic entanglement of global capitalism and eco-colonialism that has brought us both the urgent epidemiological threat of the coronavirus and global climate destruction.

Not an external force

This forces us to reconsider how we think about the relation between the virus and our political order. It really is far too simplistic to think that this virus is an intruder that threatens us from the outside.

And yet, so far most people, and politicians alike, have been hesitant to make that connection. Instead, the COVID-19 has been framed and conceptualized as an outsider, an intruder or even an invader that threatens the modern society from which it is essentially distinct. In a typical move, President of the United States Donald Trump referred to COVID-19 as a ‘Chinese virus,’ a hypernationalized and racist metaphor designed to enhance both xenophobia and the naive belief that the pandemic is unrelated to human activity. In addition to this, in the past years he has fired the few specialists that could have helped him in defeating the epidemic.

This reaction is emblematic for the fixation on the outside and the politics of othering that most politicians and policy makers still religiously adhere to. The virus is depicted as an invader or bioterrorist who temporarily yet radically disrupts ‘our way of life’ – to paraphrase the EU slogan.

And so instead of understanding the virus as a political actor that inherently belongs to the ecosystem we have co-constructed, and rather than concluding that this virus is literally and figuratively a mutation in the global politics of neoliberal capital, politicians around the world hasten to frame it as an external enemy.

The truth is, however, that the virus is neither an aberration nor a monster: it merely reveals to us the monstrousness of business-as-usual in eco-colonial capitalism.

Not exceptional

In most European countries, politicians were relatively slow to react. The measures initially taken by most governments in the past weeks are completely consistent with the neoliberal order and were based entirely on the idea that COVID-19 is an intruder that has entered human society, independently from anything even remotely related to neoliberal politics. In addition, the initial focus was on the economic fallout preventive measures would cause – and hardly ever on the fallout the damage will bring about.

In the first stage, there was the completely non-committal and individualized appeal: wash your hands and continue working and consuming. In a second stage, governments throughout the world gradually took more extensive measures, although without placing too much of a burden on the global supply chains, or production and consumption.

While China is slowly recovering from the outbreak, Australia and most European countries have now reached the third stage, with the United States lagging behind. Italy, Spain, Austria, France and Belgium are in a complete lockdown. Germany has banned all gatherings of more than two persons, Hungary is planning on announcing an indefinite state of emergency. The European Union has temporarily closed the Schengen zone and many countries around the globe have closed their national borders. The seriousness of the situation has finally sunk in: all social and economic life has been brought to a near standstill, with – mind the metaphor – only vital sectors still running.

But still, most people and politicians seem unable or unwilling to rethink our relationship with the ecosystem in earnest. Most of us still think about the current situation as a state of exception, or perhaps as just another opportunity for authoritarian regimes to further their control over people (which is true). These measures are framed as an exceptional strategy for feverishly driving out the virus from the body politic. Writing from the Netherlands, where we live, we have heard our prime minister assure us that ‘the Netherlands is now a patient.’ Exorcize the invader, restore normality.

But what if this so-called state of exception is in fact the normality of global neoliberalism, albeit in extremis?

We do not mean this in the way the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben did, whose suggestion in the Italian newspaper Il Manifesto that the government had invented an epidemic (‘l’invenzione di un’epidemia’) to legitimate authoritarian measures has not aged well. Although, to be fair, the speed with which some rightwing neoliberal and illiberal regimes have used this crisis to close down borders and rule by decree should prompt some reflection.

Instead, what we want to emphasize is that it is no coincidence that neoliberal and illiberal governments across Europe and in Australia tend to privatize the political fight against the virus as much as possible and aim to protect the accumulation of capital against the absence or refusal of labour. Quite to the contrary, this has everything to do with how neoliberalism has always tried to contain the politics of solidarity and how it has used labour as a disciplinary force.

The politics of containment

Neoliberalism has always been primarily a politics of containment. Through careful dosage and channelling it seeks to contain any real democratic politics; that is to say, a politics based on collective solidarity and equality. Like the coronavirus, democratic politics is a threat to the primacy of the market. Friedrich Hayek, one of the main progenitors of neoliberalism, was pretty clear on the matter: ‘Politics must be dethroned,’ he wrote in Law, Legislation and Liberty (1979).

Any attempt to change the way we think about politics, any attempt to drive home the urgency of the climate crisis and the necessity and possibility of solidarity, has been blatantly scorned by politicians. From left to right, there sounded the adage that now suddenly feels weirdly out of place: ‘there is no alternative.’

For is there really no alternative? Paradoxically, the current measures to contain the corona pandemic cast a completely different light on the matter.

Experts all seem to agree on one issue: social distancing and isolation is the best way to contain or slow the spread of the virus. In practical terms, this means that one of the major arteries of our economy must be temporarily cut off, or completely rewired: the streamlined 8-hour working day.

The collective self-isolation and social distancing we now willingly adhere to has all the formal characteristics of a general strike. As labour falls back on the technologies which already structure work, this simulation of a general strike seems awkwardly apt. At the very least, it is an extensive experiment in working from home; and potentially this could also become an experiment in taking back some control over our own time and our waking hours, an emancipatory promise warped by the neoliberal fetishization of flexibility and mobility. We have also accepted that, during this period, there will be less work done, and indeed that there will be less work. We are witnessing the vague contours of a shorter working day and working week.

Combatting the virus by way of self-isolation and social distancing has the unintended side effect of showing us how the organization of much of paid labour is intimately connected to the destruction or preservation of the ecosystem that encapsulates all of our lives. Fighting the virus means fighting work.

And so despite the eerie, dystopian situation we are in, there is this one shimmer of utopia: we are working less, with more control over our own time. A dim shimmer, to be sure. It is also crucial to remember that fighting work and fighting wage labour are two distinct, though potentially simultaneous, political acts. Indeed, while the 1968 revolutionaries demanded the abolition of wage labour, they instead got the abolition of stable jobs. It resulted in the massive precarity of workers that are now excluded from this utopian shimmer and instead must suffer either immediate income loss or the danger of infection as they sustain a paralyzed mass of home labourers with food delivery.

An outbreak of politics

It is interesting to note that the measures taken to ward off the threat of COVID-19 are virtually identical to the measures that climate activists have been demanding for decades: less travel, less work and less environmental expropriation. To bring global heating to a standstill, they argued, we need to focus on degrowth – and that means working less and dismantling the global supply chains. As going to work has become a matter of life and death, it is now clearer than even that work is both thoroughly political and ecological. We simply need to extend this logic to the wider threat of ecological collapse.

Now that we have reached this political moment, we must break with business as usual and the neoliberal politics of containment. We need an outbreak of politics. The corona pandemic is an immense human and social tragedy; but in spite of, or maybe because of this, it should also be a real turning point.

We must politicize these events. Official politics has opened the door by bluntly relying on solidarity and mutual aid in the fight against COVID-19, trading off some containment of the virus for the containment of politics. It is exactly this kind of solidarity that neoliberalism has been freeloading on for the past couple of decades.

It is time to say: no more. It is time to push through. Now that we have had a first glimpse of what is possible, it is time to kick in the door.

It is necessary

We should start by thinking differently about the relationship between society and the ecosystem. We simply can no longer afford to see that ecosystem as a pure ‘outside’ that stands over and against society; an ‘elsewhere’ that we can endlessly exploit, expropriate and exhaust. The coronavirus outbreak requires a different attitude. As Bruno Latour made clear: our ecosystem is, in all its complexity, a political actor that is as much a part of our society as the average citizen. Culture and nature are not opposed to each other, but irrevocably intertwined.

Just as the coronavirus is part of society, the way we organize our communal life and the way we work is inextricably linked to a much more comprehensive ecosystem. This is the great lesson to be learned from this ecological catastrophe.

So if we want to escape neoliberal containment, we must use our democratic and political power to connect these two themes: our relationship to the ecosystem and the organization of life and work within it. It points to the large-scale transformation of our society often captured in the rallying cry for a Green New Deal. No bail-outs for big business, but a bail-out for the people and the planet. This requires large public investments to make our societies climate neutral, implementing policies of degrowth, and a different social relation to our environment. Naturally, the benefits and burdens must be shared fairly, as we realize an alternative organization of work.

We already knew that it was necessary. The COVID-19 pandemic makes it clear that it is also possible.

This article was originally published in Dutch in De Groene Amsterdammer.

Published 23 March 2020

Original in English

First published by De Groene Amsterdammer 18 March 2020

© Bram Ieven / Jan Overwijk / Der Groene Amsterdammer / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Global capitalism took a surprise hit when the container ship Ever Given ran aground, bringing mass transportation to a standstill. An environmental protest could not have staged a more spectacular blockade: the incident points to a murky history of worker exploitation, intensified fossil fuel consumption and racist quarantining.

Talk of a new Cold War between the US and China emphasizes military capacity and economic prowess. Warrior discourse presents a mono-dimensional situation in which conflict is inevitable. But couldn’t China’s stratospheric rise be better understood and handled by looking at the cultural complexities behind its advances?