Overwhelmed and underserved camps are in no condition to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks. The European Union’s response so far is falling short in protecting refugees from the pandemic. The Eurozine miniseries reviews recent restrictions on mobility.

This article is the fourth part of our miniseries on refugees’ and asylum seekers’ situation in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read Bilgin Ayata’s introduction here, Chiara Pagano’s report from Italy here and Artemis Fyssa and Bilgin Ayata’s account from Greece here.

In her address to the nation on Wednesday 18 March, German Chancellor Angela Merkel impressed upon the country’s people that they should take the coronavirus crisis seriously. Merkel emphasized the urgent need for people to restrict their own movements and contacts to the absolute minimum. Yet she stopped short of imposing the kind of government controls which Italy and a growing number of other European countries have introduced to tackle the crisis. Referring to her own experience of growing up in the GDR where she could not travel freely, she insisted that democratic states should not move lightly to restrict people’s individual freedom: only in exceptional and temporary circumstances should institutions resort to such draconian measures.

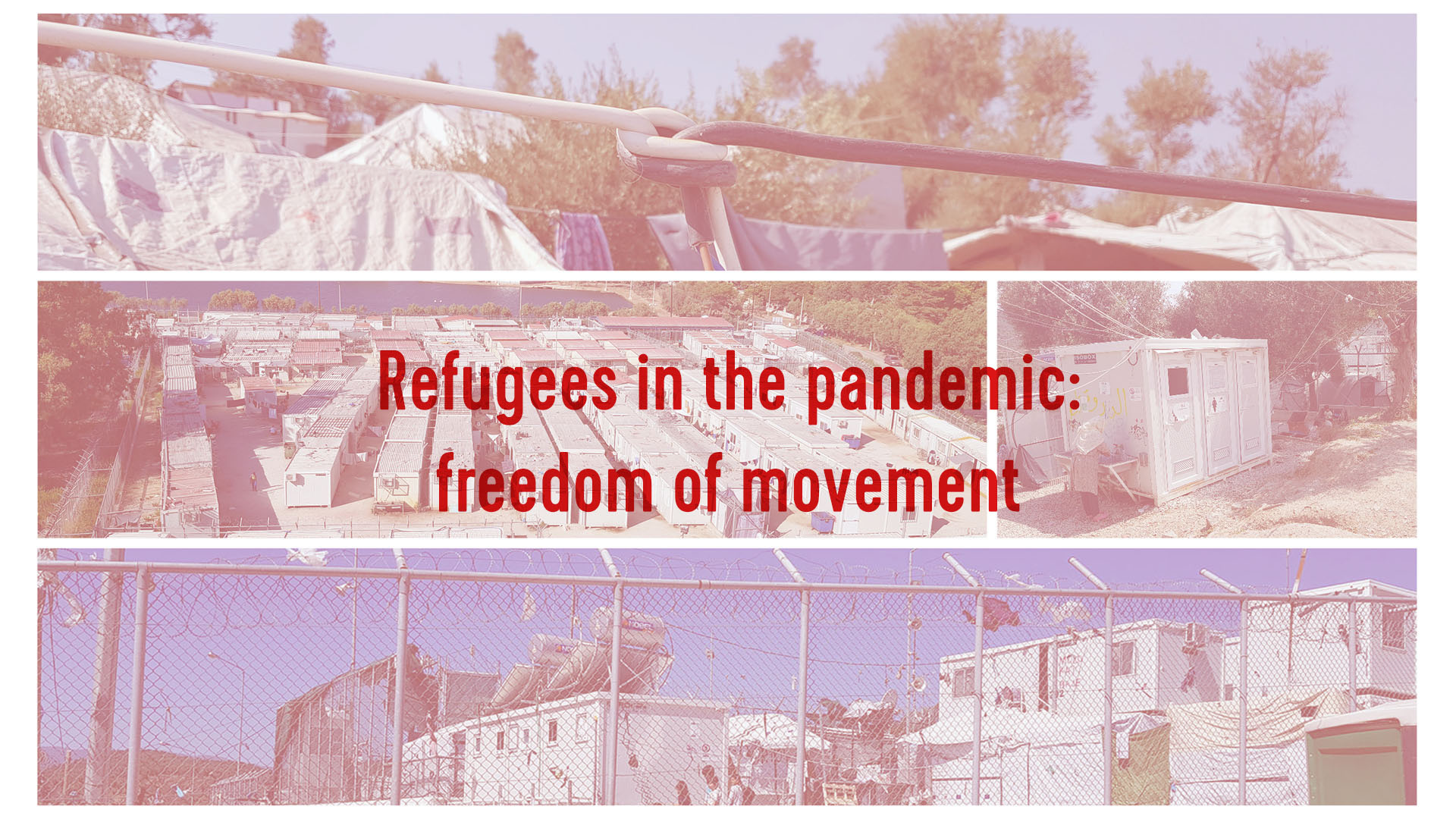

On the same day, Greece ordered such restrictions. Not on its citizens though, but on migrants living in the country’s vastly overcrowded and unsafe camps on the Greek islands bordering Turkey. Over the next month, to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, the people forcibly concentrated in these barbed-wired facilities will only be allowed to leave them in small groups between 7am and 7pm, to obtain food and essentials.

But long before these emergency measures, the inhabitants of these camps had already been effectively incarcerated — even with the gates open most times, and the majority of people actually already squatting in tents in adjacent olive groves. Since the EU-Turkey deal of March 2016, an increasing number of the people arriving have been imprisoned on the five Greek islands designated as ‘hotspots’ by the EU. They have to wait here for months, if not years, to have their asylum procedures processed by European and Greek agencies.

While waiting, or as some of them have described it, ‘slowly dying,’ they don’t have the chance to earn a living, eat properly, or live in safety. The camp food provided by the Greek military is grossly insufficient and leads to chronic malnutrition. Those who aren’t categorized ‘vulnerable’ straight upon arrival, are forced into vulnerability by the abhorrent conditions of the camp, where rape and violence are rife and basic conditions of shelter or security are lacking.

Fear of the coronavirus have only spurred protests against the conditions in these camps, where people are concentrated under catastrophic hygienic conditions. Thousands of people share a single toilet or sink without soap or disinfectant. This week, a child was killed in a fire in Moria camp on the island of Lesbos.

The new measures imposed by the Greek state will only further aggravate these conditions: rather than providing direly needed services to minimize the risk of infection, migrants will be packed together even tighter and their movements will be even further restricted. Not only is their freedom to move further curtailed, but also their freedom to escape and protect themselves from an epidemic.

If the further restrictions of movement are imposed as planned without any improvement in basic living conditions, these EU-funded facilities, which are in essence concentration camps, may as well turn into death traps. Democratic leaders such as Merkel cannot continue to stand behind such European policies of deliberate neglect with lethal consequences.

Political voices and initiatives have since emerged to avoid such a catastrophe. On 20 March, two members of the European Parliament, Birgit Sippel of the German social democrats and Erik Marquardt of the German Green party, each launched a petition calling for the evacuation of the Greek refugee camps.

On 23 March, the European Parliament responded with a letter to the European Commissioner for Crisis Management, urging to evacuate the Greek camps. Yet, even though it acknowledged the sheer impossibility of implementing social distancing and hygiene measures in the camps, the letter called only for the preventive evacuation of those at high risk — those older than 60 and with preexisting health conditions.

In response, the EU Commissioner Ylva Johansson announced an action plan to improve healthcare in the camps, to implement isolation measures for the sick and elderly, and to evacuate unaccompanied minors. Focusing on these vulnerable groups, the plan leaves open the possibility that the majority remain in the camps, thus leaving a chronically underfed population in a situation in which it is impossible to escape a virus that will be lethal to at least some of them — and probably at a rate much higher than seen in the general population.

As the attempt to protect Europe against the coronavirus meets longstanding efforts to protect Europe against refugees, it seems the right of refugees to protect themselves from the virus is easily sacrificed.

The coronavirus is hardly the beginning of a humanitarian crisis, and on a moral and political level, a crisis of humanity. The pandemic only makes these long-standing crises more visible — and not just in Europe.

The United States runs the largest migrant detention system in the world, with a long and dark history of inhumane and lethal treatment and with asylum seekers regularly being denied access to legal counsel. Since the outbreak, detainees have expressed fears about coronavirus infection in ICE detention facilities, where it is impossible to adhere to the social distancing measures needed to curb the spread. Several coronavirus cases amongst detainees and staff have already been confirmed. In response, some 60 people staged a hunger strike demanding protection, but they were forced to end the strike after being threatened with solitary confinement.

Australia’s equally notorious system of migrant detention, parts of which are on remote islands legally cut off from its sovereign territory in order to create a permanent state of government unaccountability, has responded similarly to the coronavirus threat. Despite calls to release the inmates of detention centers in which health controls cannot be maintained, Home Affairs officials have claimed plans are in place to manage potential outbreaks.

Refugees in these western democracies are not only being deprived of the freedom of movement, and in some cases of the right to claim asylum; they are now deprived of the right to protect themselves against disease.

If, as Merkel claims, democratic states should only obstruct the freedom of movement of people — those not convicted of any serious crime — in ‘exceptional and temporary circumstances,’ they cannot possibly legitimize permanent policies to detain asylum seekers under the reported conditions. Even less legitimacy can exist for the lethal pushbacks against asylum seekers trying to reach their territory in search of safety and survival — most recently shooting live ammunition at unarmed people crossing a border.

If the coronavirus epidemic can offer any instruction, it is that democratic institutions cannot keep defending their ongoing regime of mass incarceration that brings death with it, both slow and immediate, under the euphemisms of ‘administrative detention’ and ‘migrant deterrence’. When humankind will finally overcome this global health crisis, and EU citizens can hopefully restore their collective freedom of movement, what freedom will remain for those who most need it?

This article is the fourth part of our miniseries on refugees’ and asylum seekers’ situation in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Read Bilgin Ayata’s introduction here, Chiara Pagano’s report from Italy here and Artemis Fyssa and Bilgin Ayata’s account from Greece here.

The miniseries is the result of a co-production with the research project ‘Infrastructure Space and the Future of Migration Management: The Case of the EU Hotspots in the Mediterranean Borderscape.’

The limits of protection, prevention and care

A miniseries on refugees in the COVID-19 pandemic

From national threat to oblivion

Erasing migrants from public discourse in Italy during COVID-19

Politics of abandonment

Refugees on Greek islands during the coronavirus crisis

Published 15 April 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Kenny Cupers / Research Project ‘Infrastructure Space and the Future of Migration Management: The Case of the EU Hotspots in the Mediterranean Borderscape’ / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The Second World War no longer serves as a history of the western European present. The current era is marked by a different set of problems, not least the fading appeal of the model of democracy installed after 1945.

Steady access to safe, drinkable water is still a privilege, and Europe is struggling with ever-worsening droughts. The new episode of the Standard Time talk show discusses chemical hazards, eco guerrillas, and why we can never have enough pelicans.