The end of Tunisia’s spring?

Kais Saied’s power grab in Tunisia did not take place in a vacuum. A combination of constitutional dysfunction, a self-serving party system and festering social tensions had left the country at breaking point. Now the man many hailed as a saviour threatens the achievements of the democratic revolution of 2011.

With more than a decade of democratic advancements behind it, Tunisia has for the last two years been poised over the abyss of autocracy. During that time, observers have often declared the death of Tunisian democracy. So often, in fact, that it’s hard to remember when exactly it was that Tunisian democracy expired.

Was it when President Kais Saied extended emergency rule a month after his power grab on 25 July 2021? Or when, on 22 September, he confirmed that parliament would not return, and that Tunisia would be ruled by presidential decree pending constitutional overhaul?

Was it when, on 5 February 2022, Saied dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council and instated his own loyalists, firing dozens of judges soon after? Or when he shoved a new constitution down the throats of the people through a widely boycotted referendum in July?

Did Tunisian democracy die after the parliamentary elections in December 2022, in which roughly 10% of the populace participated? Did the lights go out in February 2023, when politicians and others critical of the president – including Noureddine Boutar of Mosaique FM – were arrested on charged of violating Decree-Law 54, Saied’s ‘Cybercrime Law’?

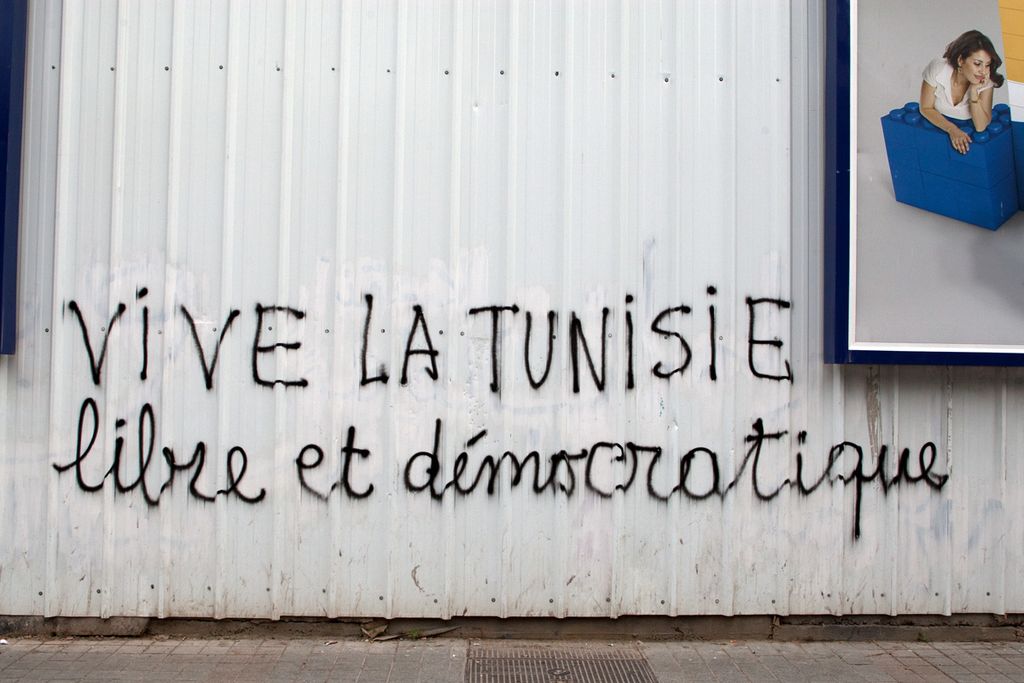

Photo by Jerzystrzelecki via Wikimedia Commons

Or was it in April, after the alleged banning of The Tunisian Frankenstein, a collection of essays whose title compared Saied to the eponymous monster? (The decision was abruptly reversed after criticism lit up social media – a ‘surreal move’ as the author Kamel Riahi put it.)

Whether or not Tunisian democracy is beyond the point of resuscitation is open to interpretation. (We tend to think that as long as Tunisians continue to fight for it, democracy cannot be definitively deemed dead.) More incontrovertible is that Tunisian politics is at an impasse. Its president has not managed to stamp out opposition to his one-man pathway toward steep ‘degeneration of democratization’.

Neither, however, has the opposition mustered the political momentum and minimal consensus on values, vision and strategy to stop Saied’s onslaught. Tunisia’s much-vaunted civil society organizations have also left much to be desired in their defence of democracy.

Worldwide, of course, democracy is ‘spluttering’ too, as John Keane notes. This article parses the current Tunisian deadlock and assesses the country’s stumbling democratization.

25 July 2021: Breaking point

Tunisia’s democratic reversal ushered in by Saied’s power grab did not take place in a vacuum. The country was already rife with discontent. In the capital, people’s mounting frustration and anger peppered every conversation, formal and informal. Passers-by, service workers, shopkeepers, students, the unemployed, party members, activists, university faculty, friends and interviewees all complained about political sclerosis, rising prices and deteriorating living conditions.

At the time the COVID-19 pandemic was wreaking its fatal havoc, the newspapers reporting the daily death toll. Prime Minister Hichem Mechichi’s government seemed incapable of constructive action, parliament under speaker Rached Ghannouchi seemed paralysed in its fractiousness, and President Kais Saeid’s almost comical warnings of conspiracies were outmatched only by his unwillingness to work with the other branches of the executive.

On 25 July, Republic Day, the country exploded. Angry protestors braved the scorching heat to denounce Mechichi, Ghannouchi and the entire parliament. The political and social tension was unsustainable. A showdown loomed. It felt like Tunisia was at breaking point.

And indeed it was. A few hours later, flanked by the country’s top brass, Saied made a night-time appearance on national television, making a momentous set of proclamations. Invoking the popular rage, the president announced the activation of Article 80 of the 2014 Constitution. He suspended parliament and lifted immunity from MPs and former government officials.

Police and the military seemed to pledge tacit support for the president’s abolition of the separation of powers. Tanks stood before a locked parliament in Bardo and around the Ibn Khaldun statue in Habib Bourguiba Avenue. Saied’s claims to be representing the stolen will of ‘the people’ found resonance with many Tunisians. Protestors poured onto the streets, celebrating the man many hailed as the saviour of the people. According to the dominant (i.e. state-sanctioned) narrative, he would deliver the country’s countless disaffected from the machinations of the post-2011 political class – from corruption, from socio-economic misery, even from COVID-19!

Ever since, there has been a pre- and a post-25 July Tunisia. Saied’s power grab set off alarm bells for many at the time; but nearly two years later, it is abundantly clear that his project has set back the country’s democratic transition to an extent unimaginable at the time. Thus far, Tunisia has failed the tall order of sustainable democratization. How and why is the puzzle confronting us all.

Incomplete institutionalization

Like any political phenomenon, democratization involves both formal (top-down) and informal (bottom-up) procedures, actors and behaviours. From the top, one significant obstacle to the sustainability of Tunisia’s democratization has been the failure to complete the building of democratic institutions.

This might seem surprising. After all, the post-2011 political scene boasts impressive institutional and procedural gains. There have been consecutive elections in 2014, 2018 and 2019. Even after President Beji Caid Essebsi’s death in July 2019 and rumours of a failed coup, the country did not veer from the election path.

The Speaker of Parliament, Mohamed Naceur, took over until early presidential elections were organized. After an almost ludicrous campaign, most of which one candidate (the notoriously corrupt media mogul Nabil Karoui) spent in prison, Tunisians elected a relative unknown – Kais Saied – in September 2019. The 2014 Constitution also catapulted Tunisia’s democratization into top gear.

So what was missing? Above all, a Constitutional Court. This was the gaping hole in the scramble for institution-building after the revolution. As Article 118 of the 2014 Constitution stipulated, the Court would be comprised of 12 members, each serving nine-year terms, to be chosen by the president, the parliament and the Supreme Judicial Council. This judicial review body would ‘oversee the constitutionality’ of laws and treaties, as Article 120 elaborates.

Yet this court never came to be. Parliament, whose makeup was especially fragmented after the 2019 elections, could not decide on its nominees. After much criticism for holding up the process, parliament passed a bill in spring 2021 that would reduce the proportion of votes necessary to select Constitutional Court judges. But Saied vetoed the bill, not only leaving the country without a supreme court, but also heightening tensions between the president and parliamentary speaker, the Ennahda leader Rached Ghannouchi.

A Constitutional Court would have undoubtedly declared the unconstitutionality of Saied’s controversial implementation of Article 80, which allows for the President to enact emergency powers as long as parliament is ‘in a state of continuous session’ throughout. But although Saied’s freezing of parliament violated the basic conditions for the activation emergency powers, there was no Court to keep him in check.

The inability to birth this judicial body into being left Saied free to make other moves, including replacing the Supreme Council of Judges, suspending the Anti-Corruption Authority, governing by decree even in matters as consequential as amending the election law, and violating due process in the case of the growing number of political prisoners. The Court would have been key to preventing a new round of authoritarianism and have made Tunisia’s democratization more sustainable. It was not to be.

Deficient formal rules

Related to the unfinished institutionalization of Tunisia’s political institutions since 2014 have been deficiencies and contradictions in the rules codifying procedures and responsibilities. It turned out that the celebrated Tunisian constitution could not protect itself. Passed by an overwhelming 200 members of parliament in January 2014, the most democratic constitution of the Arab world had a lifespan of only seven years.

No constitution is perfect, but Tunisia’s version floundered dramatically. Above all, it gave the president article 80. Even had the Constitutional Court been functioning, article 80 places massive powers at the president’s disposal. All it takes is ‘imminent danger threatening the nation’s institutions or the security or independence of the country, and hampering the normal functioning of the state,’ for the President to call for ‘any measures necessitated by exceptional circumstances.’

If we learned anything from the US-led ‘War on Terror’, not to mention the habitual emergency rule of long-serving Arab autocrats, it is that ‘imminent danger’ is a slippery slope. Even in established democracies, national security (or ‘counter-terrorism’) is often a pretext for breaching civil liberties and overstepping constitutional or legal prerogatives. Saied accused parliament itself of posing ‘imminent danger’ to the Republic. It was not difficult to convince a public already disgusted with parliamentary shenanigans that MPs were ‘hampering the normal functioning of the state’.

Other snags in the 2014 constitution pertain to the balance of powers. The President of the Republic, whose formal mandate is largely limited to foreign policy, has not been able to keep out of parliamentary affairs. Unlike in a pure Westminster system, the prime minister was not automatically the head of the majority party. Rather, he and his government (or, in theory, she and her government) would be voted in through a separate parliamentary vote. This meant haggling and horse-trading between parties and parliamentary blocs.

The Islamist Ennahda won a plurality in the 2019 parliamentary elections, but its nominee, the independent Habib Jemli, was unable to form a government. The next nominee (chosen by the president, as per constitutional provision), the independent Hichem Mechichi, was able to form a government, but with no party majority behind him. The tenuous coalition between Ennahda, Qalb Tounes and Etliaf Al-Karama was deeply unstable, with parties and blocs shedding members routinely. Sometimes, the ruling coalition relied on other parties (theoretically, the opposition) to pass its bills. And so on.

Additionally, the contest between Tunisia’s ‘three presidencies’ (President of the Republic, Speaker of the House, and Prime Minister) was unending. Mechichi, who had at first been Saied’s man, was co-opted by Ennahda, whose head – Ghannouchi – was Speaker of Parliament. Eying the presidency in 2024, Ghannouchi stepped on Saied’s toes. His diplomatic visits to Turkey and Libya, and the endless (and endlessly photographed) stream of international visitors to his office in Bardo, threatened Saied. Ghannouchi was contentious in parliament, too, only just surviving a confidence vote in July 2020. The weakness of the constitutional arrangement was thus compounded by a clash of (equally ambitious) personalities.

Finally, the 2014 constitution over-promised on social rights. Of course, it is the right of every Tunisian (and every human being on earth) to have access to work (article 40), clean water (article 44), a clean environment (article 45) and regional development (articles 136, 139). However, in a poor country on the European periphery, with internal peripheries of its own in the south and the interior, writing these rights into the constitution has fed frustrations. Political under-performance, the neglect of social rights, and the unwillingness or inability to reverse social inequalities and exclusions dating back to independence are all magnified as egregious constitutional violations.

Perhaps setting the bar too high in a transitional, economically developing country exacerbates legitimate public discontent. Be it the jobless youth who exit the country in harqah death boats, members of the Kamour campaign in southernmost Tatatouine who demand a share of their region’s oil wealth, or the residents of polluted Gabes or the Gafsa phosphate basin – all appeal to their constitutional rights. Here, the failure of the progressive Chilean constitutional referendum in September 2022 comes to mind. In Tunisia’s case, dashed revolutionary hopes dovetailed with flouted constitutional promises. Saied could never have carried off 25 July had not deep-rooted disenchantment with the ruling class taken hold of most Tunisians.

Weak, divided intermediaries

The behaviour of Tunisia’s political intermediaries – above all political parties and civil society actors – has been another factor in the derailing of the country’s democratic transition. Political parties have demonstrated an obsession with power. Since the revolution, no proper opposition has formed in parliament – no party or bloc that has been consistently critical of the ruling coalition.

After coming second place in the 2014 parliamentary elections, the Islamist Ennahda (69 seats) decided to rule jointly with its arch-rival Nidaa Tounes (85 seats). Engineered largely by Rached Ghannouchi and the late president Beji Caid Essebssi (‘the two sheikhs’, al-shaykhain), this brand of so-called ‘consensus democracy’ brought together the two largest parties in a ruling alliance, despite being diametrically opposed ideologically. After the 2019 elections, a weakened Ennahda (52 seats) scrambled to find coalition partners, settling on Qalb Tounes (initially 38 seats), a new arch-rival whose imprisoned presidential hopeful had viciously attacked the Islamists during the campaign. This coalition was shaky from the start and unpopular within Ennahda itself.

From the outset of democratization, then, Tunisia has functioned without the benefit of a formal opposition. This void has deprived both legislative and executive powers of constructive criticism and alternative policies to deal with pressing issues: unemployment, skyrocketing indebtedness due to one IMF loan after another, crumbling infrastructure, underdevelopment and regional asymmetries, bankrupt state-owned enterprises, brain drain, treatment of irregular migrants to Italy, and more.

Second, Tunisia’s political parties have proven brittle, with little staying power. Parties win seats only to haemorrhage them soon after, dropping in numbers, impact and popularity. Too many parties revolve around individuals (and their families). Nidaa Tounes (Beji Caid Essebssi and his son Hafedh, at odds with former prime minister Youssef Chahed); Congress for the Republic (Moncef Marzouki); Al-Jomhouri (brothers Ahmed Najib and Issam Chebbi); and Qalb Tounes (Nabil Karoui) are telling examples. Ennahda has been the most sustainable with a relatively stable constituency of 25–33%, although with a diminishing share of the vote since 2011.

However, the Islamist party has notoriously struggled with the question of leadership over the past three or more years. By the time 25 July 2021 came around, Ghannouchi had not yet been coaxed to give up his position as party president. The succession issue was particularly divisive even within Islamist ranks, since Ghannouchi was angling to change party by-laws in order to stay on as leader and eventually contest Tunisia’s presidency. The lack of intra-party democracy within Ennahda set in motion a series of high-level resignations, including Abdelhamid Jlassi, Lotfi Zitoun, Abdellatif Mekki (who started his own party, Action and Achievement), Samir Dilou, and over 100 others.

The personalist inflection of parties freezes instruments and processes of internal democracy key to their longevity and sustainability. It suggests that the values among party players veer more towards self-interest than collective responsibility and the public good. Like other parties, Ennahda was in no position to fend off the presidential coup, having lost important cadres and national popularity ratings. Saied’s arrest of Ghannouchi in April, as well as senior party official Noureddine Bhiri and former prime minister Ali Laarayedh in February and December respectively, have rendered Ennahda almost inactive. Some see the party as effectively ‘dismantled’, despite assurances to the contrary from its temporary leader Mondher Al-Wanisi. Feeble parties trip up democratization, even without coups.

In addition, Saied’s anti-intermediary paradigm of direct representation (al-tamthi al-qa’idi) considers political parties (and much of civil society) usurpers of the ‘people’s will’. Parties were not allowed to run in the 2022–23 elections as such. This confluence of factors makes it unlikely that Tunisian political parties will be able to revive themselves in sustainably democratic fashion.

Less organized, more bottom-up protest movements also feed into Tunisia’s new politics. When formal intermediaries disappoint, Tunisians boycott elections and take to the street instead. The biggest success of this public mobilization was, of course, the 2011 revolution itself. Since then, however, protest movements have often failed to achieve their demands. The Kamour movement for equal distribution of oil revenues, for example, met the president and forged agreements (2017 and 2020) with two different governments, who have not held up their ends of the bargain.

Part of the reason has been the return of security state. Although this was a trend even before 25 July, it has intensified since. Burgeoning police unions have had a role in repressing protests – although conflict with the Ministry of Interior has landed some union members in prison. Still, there has been some mobilization (hirak) against the coup. Organisations such as Citizens Against the Coup and the National Salvation Front (whose leaders, including Issam Chebbi, Jawhar Ben Mbarek, and Shimaa Issa languish, in prison) still publicly defy Saied. Some diaspora organizing, including petitions by academics to release Ghannouchi and other prisoners, is also notable.

The significance of protest is another indicator of the weakness of formal political intermediaries. Tunisia’s political discourse often decries ‘lobbies’, but in fact there are no strong political pressure groups to speak of. Hence the outsize role that protest movements play as barometers of public opinion and expressions of political and social demands. One exception is the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), the largest organization in Tunisia able exert political pressure. The trade union’s historical pedigree dates back to the anticolonial struggle and has local organisations in every governorate. It can generate considerable momentum, tangling with the state over wage increases and even political conflicts.

Yet the UGTT has hesitated since 25 July, by turns attacking Saied’s rule, then muting its rhetoric. Before the parliamentary elections in December the previous year, the UGTT secretary general Noureddine Tabboubi thunderously declared that the union ‘no longer accept[ed] the current path’ taken by the president. The expulsion of Esther Lynch, head of the European Trade Union Confederation after her protest appearance in February 2023 also drew the UGTT’s ire. If it wished, the UGTT could mobilize protestors vastly and swiftly, as it did in the 2011 revolution. But there has been little follow-up. Even its general strikes have been brief and rather rare, as was the case in June 2022. It is as though the UGTT does not wish to provoke the state too much, even under Kais Saied. A half-baked initiative it tentatively announced in the spring, alongside other civil society groups, seems to have fizzled out.

In fact, the reactions of Tunisia’s civil society intermediaries to the 25 July coup were remarkably muted. Several of them – including not just the UGTT but also the Union tunisienne de l’industrie, du commerce et de l’artisanat (UTICA) and the Association of Tunisian Democratic Women – met with Saied the day after the coup. They called for a ‘roadmap’ and declared that they would be on watch lest the president overstep his emergency powers. Ambiguity over the legality and morality of Saied’s power grab among major civil society players became a pattern. Ideological polarization has led many actors to eschew being seen on the same ‘side’ as Ennahda.

It is undeniable, however, that Tunisian civil society has done much democratic learning in the way of skills, practices and values during and since the 2011 revolution. Criticism of Saied has sharpened among all intermediaries. Even party leaders who initially hailed his actions on 25 July as commendable, such as the Democratic Current’s Abbou (or her husband Mohammed Abbou), are now stringently opposed to the president.

In late May 2023, national and international attorneys, judges, and rights activists held a workshop in Tunis to ‘defend judicial independence’. One recent public campaign by the journalists syndicate was against the questioning of prominent media personalities Haythem Mekki and Ilyes Gharbi (host of Mosaique FM’s popular Midi Show) on a Decree 54-related case brought against them by police unions. (The two were released shortly after.) The syndicate has vowed to appeal a new court ruling prohibiting television and radio coverage of the so-called ‘conspiracy cases’, calling it unconstitutional.

These moves show that Tunisian civil society is far from complacent. However, civil society’s disparate members do not appear poised to work together alongside political parties. Saied’s political project has inflicted huge damage on the institutions and political entities of once-promising democratization; counteracting that necessitates cooperation for the democratic good. A political system without robust intermediaries has proven incapable of ensuring democratic sustainability.

Looking ahead: A national conference

Democratization is not ‘the only game in town’. As a moral imperative, in Tunisia it competes with the right to have socio-economic rights. The neoliberal template pushed by the gurus of democracy has lost its shine. Euro-American democracy promoters can no longer sell the fantasy that democracy is key to freedom. At least not to the have-nots, the unemployed and the indignant protesting almost daily in Tunisia. As an institutional requisite, democracy needs equal opportunity and distribution of wealth for recruiting literate, skilled and educated citizens to its ranks.

The marginals’ daily concerns and struggles are about issues of ‘bread and butter’. But ever since the government of prime minister Hedi Nouira in the 1980s, the neoliberal models of economic development underpinned by capitalist accumulation have not extended to the ranks of citizens prioritizing political sovereignty over food security.

The marginals are not devoid of political culture. Their political culture is demotic too: they protest and die for their brand of rights and demands. They are not intolerant; but they do not tolerate living as sub-citizens in regions where water and electricity are rationed, and where schools and hospitals are sub-standard. In Tunisia, postcolonial regimes have not included them in their map of diversity – or even ‘humanity’. In their public squares, the state is an ‘enemy’. Under Bourguiba, Ben Ali, and even after the revolution, equal development recurs as a broken promise. Neither compromise nor trust feature much in the marginals’ brand of political culture.

Participation and competition via periodic elections has been an arena of fierce division, pitting pre-revolutionary ideologies and imaginaries against one another. However, Tunisia’s fledgling democracy has failed to produce the institutional requisites for sustained democratization. None of parties have paid attention to the grim structural logics pushing the entire political system to the brink of dysfunction.

These include regional discrepancies in development; reduced production levels in key sectors of the economy; low rankings in major global indices of economic growth, human development and corruption; migration, lack of welfare policies, and indebtedness. But instead of addressing the biggest challenges for social and political cohesion, the political parties have been engulfed by considerations of short-term gain and political expediency, and politics reduced to strategies of re-election.

The balance of power has now tipped too much in favour of Kais Saied for dialogue to be a tool for reconciling the country. Immediate measures are necessary to decompress the socio-political tension. Neo-patrimonial approaches won’t work. To clear the ‘bottleneck’, Saied could free all prisoners unconditionally. With diverse interlocutors from within the polity, civil society and the academy, the president could plan a road map that is inclusive.

The 2015 Nobel Quartet has the skills should he go this way. By leading broad consultations involving the impoverished regions and even his opponents, Saied would demonstrate the political will for a national vision of sustainable democracy, economy, social justice and equal development. The EU, in particular, might lend him a hand in executing an agenda of reform and reconciliation. But barring such concrete steps, the political situation is set to only worsen.

Moves toward international intervention in Tunisia are materializing. Members of the G7 urged Tunisia to accept a new IMF deal. But Saied is not agreeable, and nor is the UGTT. This should not prevent Tunisians from conversing with their European neighbours and their African and American partners over democratic good practices. In recent visits to Tunis, European leaders (from Italy, the Netherlands and the EU) have promised over a billion euros in assistance, likely tied to a new IMF deal in the works. Controversially, much of the aid appears geared at combating migration to Europe. The joint statement in June 2023 announcing this new ‘partnership’ did not mention democracy.

On the other hand, a new bill proposed by two US Senators seeks to condition American aid on democratic restoration and reforms. Given these developments, the world’s main democracy promoters must also appreciate the specificities of the region’s democratic transitions. Other international actors will not save Tunisian democracy, least of all the authoritarian Gulf states, even if their largesse might prop up Tunisia’s collapsing economy.

Yet the Tunisian public remains broadly opposed to external meddling. Victory for democracy is to be achieved by Tunisians, as they valiantly and creatively proved capable of in 2011.

Published 20 June 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Larbi Sadiki / Layla Saleh / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- Living dead democracy

- Why Parliaments?

- Spelling out a law for nature

- No more turning a blind eye

- The end of Tunisia’s spring?

- Protecting nature, empowering people

- Albania: Obstructed democracy

- Romania: Propaganda into votes

- The myth of sudden death

- Hungary: From housing justice to municipal opposition

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Since the collapse of Novi Sad’s train station in November, student-led protests have erupted across Serbia, inspiring a nationwide movement against corruption.

After six months of protests, there are grounds for hope that the tide is turning in favour of the Serbian student movement: first, the unification of the opposition around the movement’s demand for new elections; second, the emergence of a strategic alliance between the students and the EU.