Austrian magazine dérive on agonistic urban democracy and new alliances from below; why tenants’ groups need to reclaim institutions; and how better communication prevents disappointment in participatory processes.

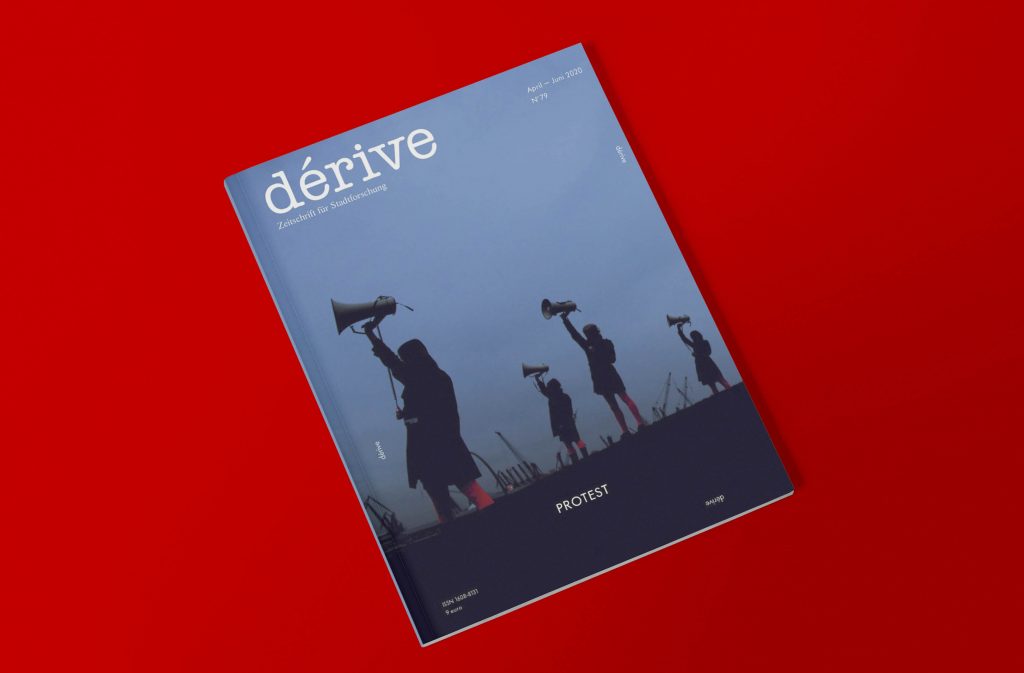

‘Despite efforts by municipal authorities to open up the democratic process, protests movements have been increasing,’ writes Lukas Franta in an issue of dérive devoted to the praxis of urban democracy. Citizens are assigned not just a social position, but also, through city planning, a spatial one. ‘The marginalized are those who have no political, economic or institutional power because of their position in the social-spatial order: the unemployed, precarious workers, migrants, the homeless.’

Coalition

Arguing for an ‘agonistic’ understanding of urban democracy, Franta discusses the potential for alliances across social groups. ‘Connections and cooperation form when parts of society feel materially or ideologically threatened by austerity or urban development policy.’ Broad coalitions can ‘democratize urban societies from below and create space for self-organization and self-management in the city. Anti-hierarchical protests and citizens initiatives can be catalysts for democratic innovation.’

Co-optation

‘Participatory processes often serve to contain dissent and conflict,’ warns Lisa Vollmer. Experience has taught campaigners to develop strategies for avoiding co-optation, ranging from boycotting official channels to disrupting or appropriating participatory processes.

Citizens’ initiatives must also acknowledge that radical self-determination is not for everyone. The feeling that decisions regarding matters of housing are best left to government is justified, particularly since ‘self-management is much less easy for people with low levels of economic capital’. Given distrust in public institutions’ commitment to the common good, tenants’ groups need to demand that welfare provision is de-centralized and made accountable. ‘Public institutions should be reclaimed for social purposes and democratized.’

Communication

Residents’ feeling that they are not being heard, and that powerful interests will always win the day, can also be caused by poor communication on the part of planners, writes Alexander Hamedinger. If the object and the aim of the process is defined in advance, without the participation of citizens, dissatisfaction will result. Conversely, planners must communicate legal and institutional parameters in order to avoid raising impossible hopes.

More articles from dérive in Eurozine; dérive’s website

This article is part of the 11/2020 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletter, to get updates on reviews and our latest publishing

Published 18 June 2020

Original in English

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Since the collapse of Novi Sad’s train station in November, student-led protests have erupted across Serbia, inspiring a nationwide movement against corruption.

After six months of protests, there are grounds for hope that the tide is turning in favour of the Serbian student movement: first, the unification of the opposition around the movement’s demand for new elections; second, the emergence of a strategic alliance between the students and the EU.