1

Every summer we spent our holidays at the improvised dacha that was our grandparents’ rural house in the vicinities of the Ukrainian city of Lutsk. There were a lot of us, the entire extended family – me and my brother, our cousins, their parents and ours, and, of course, our granny and grandpa. We enjoyed our holidays, spending the time fishing and swimming, playing football and cards, shaking bountiful fruit trees and talking past midnight with friends around the fire.

I was 15 and didn’t care much about politics. We didn’t have a TV set in our dacha – we didn’t need it. But our grandpa and our parents listened to both the Soviet radio and to the ‘voices’, as they called foreign broadcasts at the time, and we noticed – however carefree we were in our golden age – that something was up. In the margins of our consciousness, barely within earshot, menacing words such as the ‘Soviet threat’, ‘ultimatum’, and ‘counter-revolution’ appeared. We felt it was these words that were making our parents strained, forcing them to change the subject and to fall silent when we approached. After all, they were Soviet people and we were Soviet children. But we felt something was going wrong in Czechoslovakia, that a war could erupt any moment, however incredible it may have seemed under a sunny blue sky during the summer holidays.

I was 15 and didn’t care much about politics. We didn’t have a TV set in our dacha – we didn’t need it. But our grandpa and our parents listened to both the Soviet radio and to the ‘voices’, as they called foreign broadcasts at the time, and we noticed – however carefree we were in our golden age – that something was up. In the margins of our consciousness, barely within earshot, menacing words such as the ‘Soviet threat’, ‘ultimatum’, and ‘counter-revolution’ appeared. We felt it was these words that were making our parents strained, forcing them to change the subject and to fall silent when we approached. After all, they were Soviet people and we were Soviet children. But we felt something was going wrong in Czechoslovakia, that a war could erupt any moment, however incredible it may have seemed under a sunny blue sky during the summer holidays.

When the Soviets invaded, we saw that our parents were utterly depressed, as if it was their government that had been overthrown and their country raped once again by foreigners. More surprisingly still, their reaction did not surprise us.

Our parents were not dissidents but, as most western Ukrainians, they had little if any sympathy for the Soviets, for Moscow, or for communism. Like most western Ukrainians, they demonstrated formal loyalty to the regime and participated in all public rituals as required. In private, however, they were never sparing in their bitter remarks about the system, the authorities, and the entire Soviet way of life. They probably never intended us, their children, to become programmatically anti-Soviet. It could have been too dangerous in the present and too harmful to our futures. But they let their words, grimaces, and gestures fall in such a way that we couldn’t but feel their contempt for the system and their profound alienation from all its symbolic entourage.

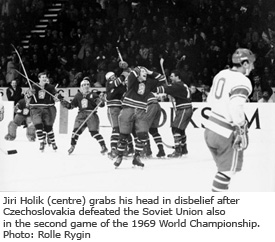

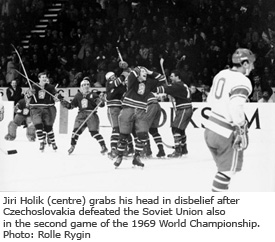

As soon as I got interested in ice hockey, I noticed that neither my father nor uncle had ever supported the mighty Soviet team. On the contrary, they always supported their opponents, whether it was the Swedes, the Finns, the Canadians, or even the Swiss. Even though the Soviets seemed to be unbeatable at the time, we hoped with all our hearts, souls, and guts that they would be beaten. When this finally happened, when the miraculous Czechoslovak team did crush them in the 1969 World Cup, we were in heaven. We cried, shook hands, and kissed one another; we were both Czechs and Slovaks at the time and we felt avenged for everything – the tanks in Prague and Muravyov’s Bolshevik troops in Kyiv, the Pereyaslav Treaty and the defeat at Poltava, the pillage of Baturyn and the 1933 famine, the ban of Ukrainian church and more, more, more.

2

I grew up rapidly during those years. By 1970, the last class of school, I already had extensive access to underground literature, including all the multiple trends of Ukrainian samvydav (a.k.a. samizdat, in Russian). Obviously, it was not my parents who provided me with all that dangerous stuff but, rather, my teacher. Or, more precisely, a school librarian – the prominent Ukrainian writer and intellectual Iryna Kalynets, who ended up at a minor position in our school after a protracted and politically motivated period of unemployment.

She noticed my interest in good literature and did her best to satisfy it from both official and unofficial sources. Interestingly, those sources included also some Czechoslovak publications from the period of ‘Prague Spring’. Primarily, it was the cultural bi-monthly Dukla, published officially in Prešov by and for the Ukrainian (Rusyn) minority in eastern Slovakia, and Ukrainian books from the same publishers that included non-Soviet Ukrainian writers banned in the Soviet Union – such as Bohdan-Ihor Antonych and Volodymyr Vynnychenko.

The 1968 edition of Dukla provided a comprehensive guide to contemporary Czech and Slovak literature and, more importantly still, to contemporary Czechoslovak politics. It contained all the major documents of the Prague Spring in Ukrainian translation, which clearly proved that there was no ‘counter-revolution’, as Soviet propaganda claimed, but rather an honest (and, as I came to understand later, rather naïve) attempt to build something like ‘socialism with a human face’.

The documents were of great value to me, since more and more friends of mine were coming back from the Soviet army completely brainwashed – persuaded that the invasion was necessary because German troops had been about to cross the border on the invitation of the treacherous counter-revolutionary government in Prague.

My next step was to learn the Czech and Slovak languages (Slovak was easier since it is much closer to Ukrainian) and to read the books and journals in the original. Ironically, many were available not only in some of my colleagues’ private collections but also in public libraries and even, sometimes, in remote provincial book stores called Druzhba (‘friendship’), where Ivan Klíma and Miroslav Holub lay covered in dust alongside the complete works of Vietnamese leader Ho Chi Minh and Mongolian leader Tsedenbal. The Soviets introduced censorship on Czech and Slovak books and periodicals as late as August, after the Warsaw Pact troops occupied the country and censorship was no longer needed. In this regard, one could be thankful for the bureaucratic rigidity and inefficiency of the Soviet system that reacted too late and, thank God, too clumsily. I remembered this 13 years later, when the Soviets introduced strict censorship on Polish books and periodicals only after martial law had already been announced, and when additional censorship became unnecessary because the Polish comrades took care of it themselves. Were it not for the sluggishness and stupidity of Soviet ideologists, I would have never read Hrabal, Kundera, and Skvoretsky in the 1970s. Nor would I have translated into Ukrainian the conceptualist poetry of Ladislav Novak and publish it as a samvydav book accompanied by Vlodko Kaufman’s provocative illustrations.

The broadly trumpeted Czechoslovak ‘normalization’ of the 1970s had its ideological counterpart in Ukraine in another crackdown on ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism’ that climaxed in 1972-73. This led to mass arrests, large-scale purges of cultural and educational institutions, and a further tightening of the Russian screw. The contacts that had evolved throughout the 1960s between Ukrainian and Czechoslovak dissidents were virtually broken off by massive repressions and all kinds of restrictions on both sides. At the time, I knew nothing about such contacts, even though I understood that neither Dukla nor Ukrainian books from eastern Slovakia could have appeared in our milieu without the involvement of Slovak Ukrainians from Prešov, Košice, or Bratislava.

Only now, with the publication of the letters and memoirs of a number of Czech and Ukrainian dissidents, can I appreciate the informal contact between Kyiv and Prague, including the prominent role in this communication played by Zina Genyk-Berezovska and other Czechs of Ukrainian origin – descendants of the Ukrainian post-Bolshevik emigration of the 1920s.

3

Czechoslovakia was the first foreign country I visited in 1987-88 – as soon as I was allowed to travel abroad during perestroika. In Prague, they thought I was Polish when I tried to speak Czech. In Bratislava, they guessed I was Yugoslavian when I tried to speak Slovak. None of them presumed I was Ukrainian, Soviet or, God forbid, Russian. I knew, however, that there were not only Russians but also Ukrainians in the Soviet Army that ‘liberated’ the Czechs in 1968. I might have been there myself had I been just a few years older. Fate spared me from this personal, though not national, shame.

I made friends in both Bratislava and Prague and brought them bags full of ‘subversive’ literature – it was a unique, though short, period in history when my country was more open, liberal, and politically advanced than theirs. We drank beer in Prague and white wine in Bratislava and I told them unbelievable things about texts that were legally published, subjects that were openly discussed, and public events that were carried out without official permission. They hoped perestroika would come to their country and I assured them that it would. It was a time of great expectations.

When it did come a year later, it was as great, elegant, and unbelievable as the victory of their ice hockey team in 1969. It really was the power of powerless. And again, for a brief but happy moment, I felt I was a Czech. And a Slovak. And a Pole. And a Hungarian.

Then, in early December, I happened to be with a colleague at Adam Michnik’s Warsaw apartment, waiting for a long-arranged interview. The host was late and Adam’s wife served us tea and apologized. And then came Adam, excited, and cried like a child: ‘Wypierdolili Ceaușescu!’ (Get lost Ceaușescu!) This was apparently a major event in his life, the accomplishment of a great dream, a victory of his team over a powerful totalitarian monster. He was a Romanian at that moment, and so were we.

I do not know how many Czechs, Slovaks and Poles felt they were Ukrainians a few years ago, during the spectacular Orange revolution. But I’m sure some did. And this is, so far, what our eastern European story is about.

I was 15 and didn’t care much about politics. We didn’t have a TV set in our dacha – we didn’t need it. But our grandpa and our parents listened to both the Soviet radio and to the ‘voices’, as they called foreign broadcasts at the time, and we noticed – however carefree we were in our golden age – that something was up. In the margins of our consciousness, barely within earshot, menacing words such as the ‘Soviet threat’, ‘ultimatum’, and ‘counter-revolution’ appeared. We felt it was these words that were making our parents strained, forcing them to change the subject and to fall silent when we approached. After all, they were Soviet people and we were Soviet children. But we felt something was going wrong in Czechoslovakia, that a war could erupt any moment, however incredible it may have seemed under a sunny blue sky during the summer holidays.

I was 15 and didn’t care much about politics. We didn’t have a TV set in our dacha – we didn’t need it. But our grandpa and our parents listened to both the Soviet radio and to the ‘voices’, as they called foreign broadcasts at the time, and we noticed – however carefree we were in our golden age – that something was up. In the margins of our consciousness, barely within earshot, menacing words such as the ‘Soviet threat’, ‘ultimatum’, and ‘counter-revolution’ appeared. We felt it was these words that were making our parents strained, forcing them to change the subject and to fall silent when we approached. After all, they were Soviet people and we were Soviet children. But we felt something was going wrong in Czechoslovakia, that a war could erupt any moment, however incredible it may have seemed under a sunny blue sky during the summer holidays.