The remarkable simultaneity of the emergence of protest movements in Western and Eastern Europe – in fact, in America too – is unmistakably intriguing. By the same token, the differences in the structure and general aims of those movements are worthy of investigation: the democratic reforms in Czechoslovakia initiated by the January palace coup in the Central Committee in Prague, the nationalist/patriotic demonstrations of young students in Polish cities in March triggered by the première of a new production of Mickiewicz’s classic play Dziady (Forefathers) and the May “festival of disobedience” on the streets of Paris staged by student groups of left-wing, Trotskyist, Maoist, and heaven knows what other ideologies. What element is common to all of them? Another question, which I consider the most important one while writing these lines, is whether there is a place for “Moscow 1968” in this collection of European capitals and American campuses that were all caught up in the sudden determination of young people to demonstrate their disapproval of the establishment and their rejection of conventional norms of behaviour and value systems.

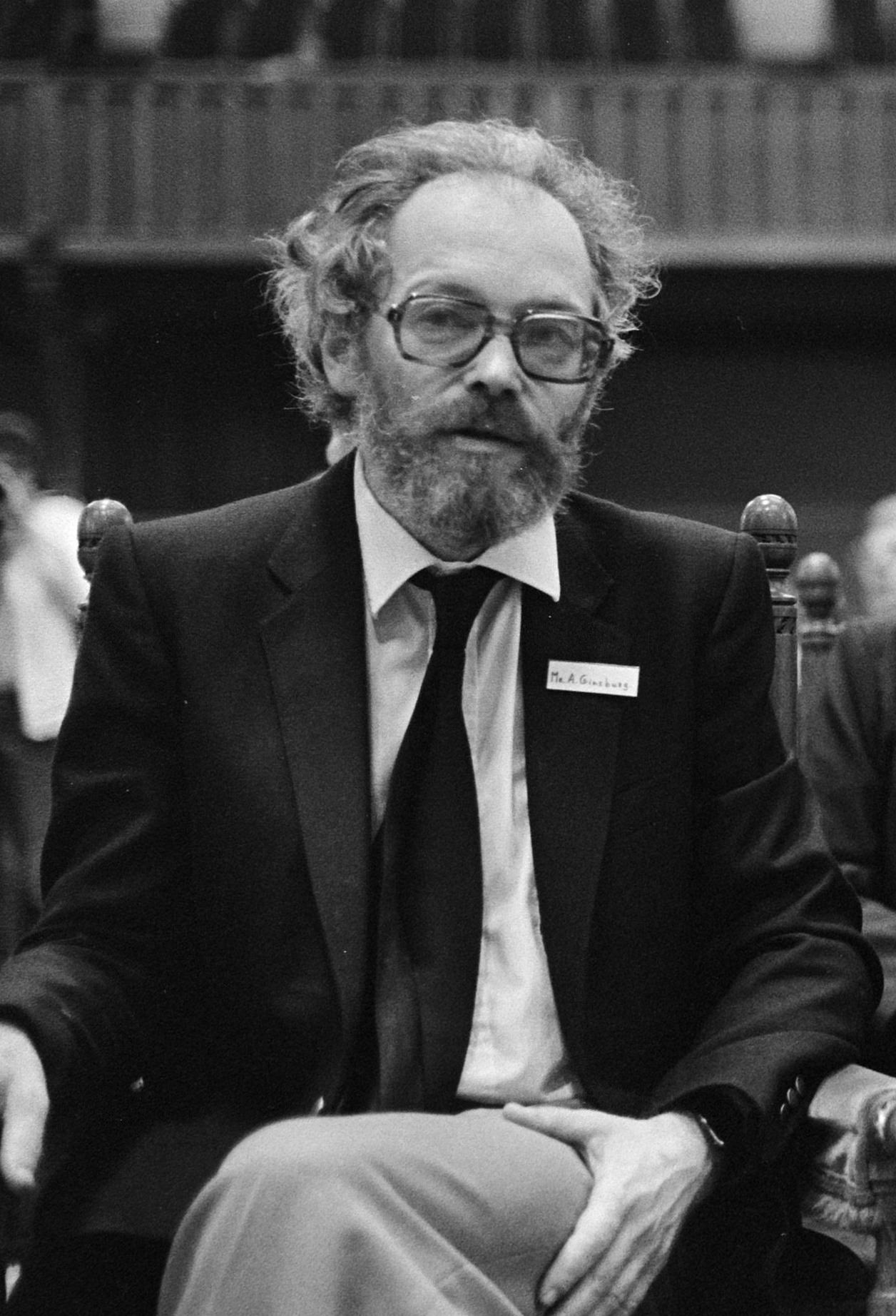

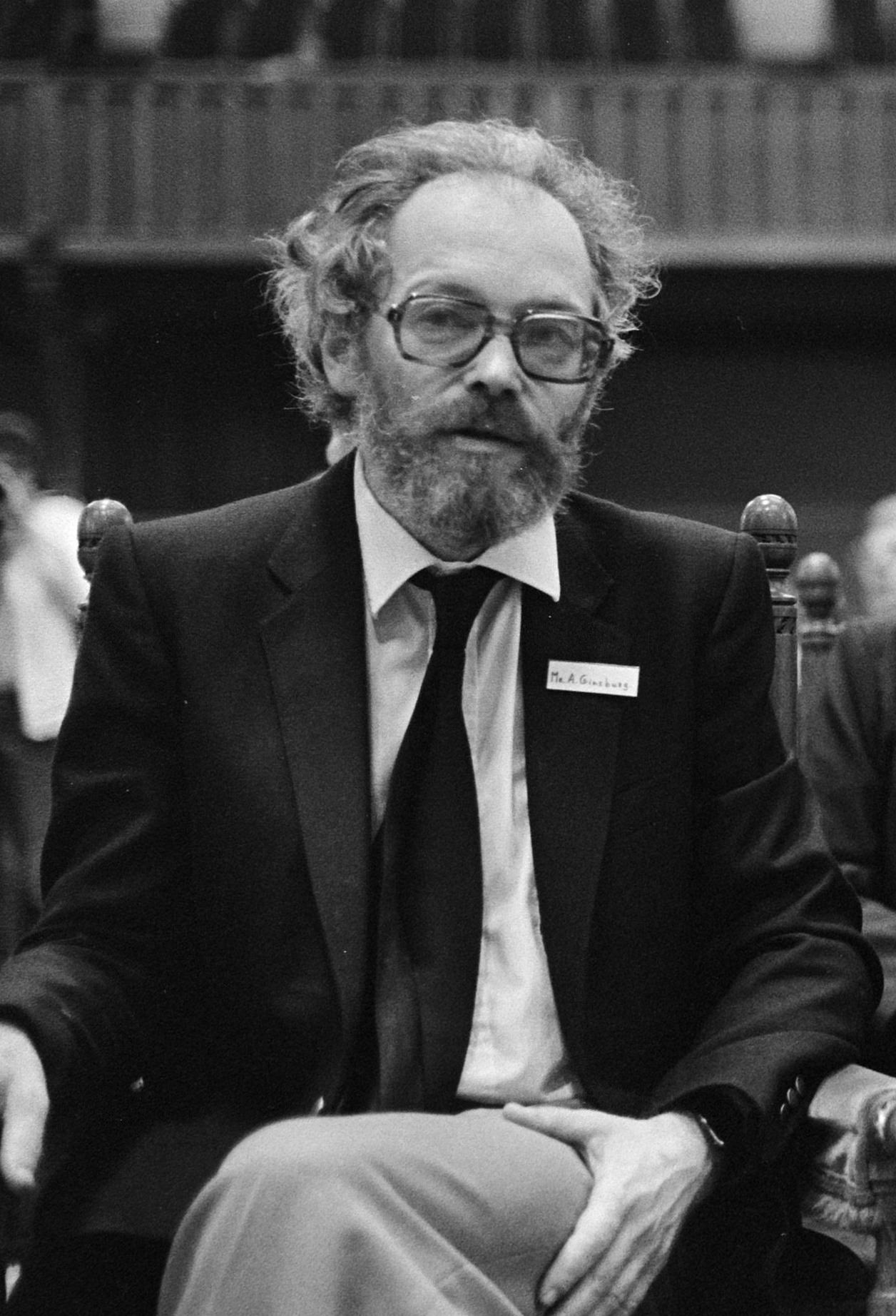

Alexander Ginzburg 1980. Source: Dutch National Archives, The Hague / Wikimedia.

In Moscow, 1968 began with yet another big political court case known as the “Trial of the Four”. Before the court stood on trial the 32-year-old samizdat editor Alexander Ginzburg, who had compiled just a year earlier a documentary book entitled Delo Sinyavskogo i Danielya (The Sinyavsky-Daniel Trial). This book, which came to be known as The White Book, recounted an earlier political trial (1966) of two writers from Moscow who received long prison terms for having secretly published their prose in the West -as it happened, the White Book was also being published outside the Soviet Union. Also on trial were Yuri Galanskov, Aleksei Dobrovolsky and Vera Lashkova, all friends of Ginzburg who had been involved in compiling The White Book and in other samizdat activities. The investigation went on for almost a year, and before the trial began, the liberal-minded Soviet intelligentsia had already received a strong impression that the trial would represent yet another step towards the country’s “re-Stalinisation”. (Discussion of whether this assessment adequately describes the actual intentions of the Soviet leadership under Brezhnev would exceed the scope of this article.) Some three years earlier, such a prospect would have driven the majority of the ‘audience’ into silent panic and caused individuals to retreat back into their protective shells. In early 1968, though, many intellectuals in Moscow and other large Soviet cities felt both the inclination and the strength to offer resistance to such a development. This mindset was, no doubt, fostered to a large extent by the news coming out of Czechoslovakia, where the political rhetoric of the new leadership of the party and the country sounded more and more like the protesting rhetoric of the liberal-minded in Moscow with each passing day. This analogy raised hopes – after all, one of the triggers of the process leading to the downfall of Antonín Novotn and Alexander Dubchek’s rise to power had been the protests of writers and students in 1967.

In the case of the Soviet intellectuals, neither their sympathy for the “socialism with a human face” heralded in Prague nor their antipathy for Brezhnev’s “developed socialism” implied any significant ideological preferences. Among those following the events in Czechoslovakia with eager attention were few convinced adherents of the communist idea (whereas they were, as it seemed, in the Czechoslovak Central Committee), and there weren’t many convinced anti-communists either. In the ranks of the “opposition-minded” intelligentsia, the whole range of the ideological spectrum was represented, from anarchists to monarchists. Naturally, there were some communists, and socialists as well, and people of generally leftist thinking, but by no means did they outnumber the Western-style liberals or the nationalists/pochvenniks. However the liberals, and the pochvenniks, did not predominate either – many, if not the majority of the intellectuals had no ideological preferences at all. They felt inclined to take an indifferent or even a distrustful view of any ideology. They weren’t interested at all in the first part of the Prague slogan “socialism”, but rather only in the “human face”.

Thus, society (not the entire society, of course, but the part that did care) awaited news from Prague with bated breath. They also looked for news from Kalanchevskaya Street in Moscow, where the “Trial of the Four” was being held at the Moscow City Court.

A sinister picture emerged from the sketchy news leaking out of the courtroom: it appeared that the trial’s organisers had abandoned any pretence of genuine judicial procedure and were steering the trial towards a guilty verdict, not flinching from manipulation or falsification. The trial was conducted in this way, and initiated in the first place, in order to demonstrate the regime’s determination to put an end to the open expression of dissent in the U.S.S.R. Spectators were not allowed into the courtroom – even though the trial had officially been declared public, and supporters of the accused stood for days on the street in front of the Moscow City Court as a kind of counter-demonstration. But that did not seem to be enough: one felt the urge to protest in some non-trivial way, to do something beyond sending the fruitless, somewhat boring petitions addressed to the regime.

On 11 January, the third day of the trial, foreign radio stations broadcasting in the Soviet Union interrupted their programmes to read “an important document just in from Moscow.” The document was the Obrashchenie k mirovoi obshchestvennosti (Petition to the World Public) by Larisa Bogoraz and Pavel Litvinov; both authors were already well-known for their protest activities. Bogoraz and Litvinov listed in great detail all the violations of law and justice that they knew were being committed in the rooms of the Moscow City Court. They also reminded their readers of the catastrophic consequences that the population’s indifference had had for the country during Stalin’s reign of terror. They concluded their petition with a call for the mobilisation of the Soviet and world public in order to fight for the reintroduction of justice.

It does not really matter, though, exactly which historical analogies were used to support that petition or what it was calling for. What was unprecedented and stunning for their compatriots, as well as for all insightful outside observers, was not to be found in the content of the text, but in how it was addressed and to whom: as a direct appeal to world public opinion (i.e. to both the outside world and Soviet institutions!). Today it is difficult to understand, to picture what kind of revolution this represented in the minds of the recipients. Until then, protests – even those intended for publication abroad – had always been formally addressed to Soviet state or party institutions, to the Central Committee of the CPSU, to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, the Supreme Court, the Attorney General’s Office, etc., or in the worst case, to Pravda or Izvestiya. Addressing petitions in this way represented a kind of umbilical cord, connecting the petitioners to “their” Soviet regime, as if to say, “Well, we don’t like certain reversions to Stalinism that we have been seeing in our lives; we consider trials, like those against Brodsky or Sinyavsky and Daniel to be political mistakes, damaging to the political reputation of the Soviet Union, but we are loyal Soviet citizens, and we are expressing our discontent not to just anyone, but to competent Soviet institutions.” The Bogoraz/Litvinov petition retained the legalist approach of earlier petitions with respect to its content, protesting the violation of Soviet legal principles Nevertheless, it struck its readers as unbelievably rebellious: Soviet citizens caught up in a dispute with their regime had addressed their appeal for support directly to the outside world for the first time!

Moreover, this represented a strike against one of the standard elements of Soviet psychology, one which had been cultivated over many decades: the concept of “hostile encirclement”, the complex of the “besieged fortress”. To appeal to world public opinion, to the “enemies” – i.e. airing dirty laundry in public – was equivalent to treason, to betrayal of the homeland.

It is remarkable, how unresistingly these concepts had collapsed in the minds of the Soviet intelligentsia within a few hours of the announcement of the “Petition to the World Public”. There was not so much as a shadow of condemnation for the two who had committed “sacrilege” in liberal circles; on the contrary, there was nothing but excitement about their impudence, even from those who would not have risked following their example. Obviously, the bogeyman of “hostile encirclement” had lost its potency in the 15 years since the death of its creator, remaining in the psyche of the informed public only through a kind of inertia. At any rate, on 11 January, the Iron Curtain definitely revealed a new, substantial breach – though, admittedly, it had not crumbled into a heap of rust.

The regime suffered a clear defeat in the “Trial of the Four”, despite the long prison sentences issued to the two main accused, Ginzburg and Galanskov (the latter would never regain his freedom – he died in 1972 in a camp hospital after an unsuccessful abdominal operation). The “epistolary revolution” had entered a new stage.

In the second phase of the petition campaign, the open letters went beyond merely protesting certain specific cases of unlawful treatment and entered the realm of criticising the system. Discussion turned to the suppression of civic freedom, the persecution of dissidents and the slide towards re-Stalinisation of the regime under Brezhnev. This movement towards re-Stalinisation deserves particular attention. Today’s cultural historians are surprised to conclude that the first two to three years of Brezhnev’s rule, which are associated in the public consciousness with an attempt to steer the country back to Stalin, were actually very liberal and productive years for the literature, the arts, cinematography, theatre and science. To say the least, those years saw distinctly more freedoms than had the final two to three years of the rule of that petty tyrant Khrushchev, the persecutor of abstract art, jazz and genetic science. This discrepancy between the real state of affairs and the public’s perception is fairly easy to explain: the public’s assessments were simply not based on the actual state of affairs but reflected the expectations within the society, which had been growing higher since 1956; in other words, expectations to which the Soviet leadership could not and did not want to respond, and would not have been able to satisfy. “Neo-Stalinism” in the country was measured not by its real level, but by the growing discrepancy between the society’s expectations and reality.

Andrei Sakharov’s work Razmyshleniya o progresse, mirnom sosushchestvovanii i intellektualnoi svobode (Reflections on Progress, Peaceful Coexistence and Intellectual Freedom) became a manifesto for those expectations, one more shaped like a minimal programme of necessary reforms than a criticism of the system. Twenty years would pass before a new generation of Soviet leaders grew to recognise the wisdom of launching such a project to modernise the country. Reading that essay by the Soviet Union’s greatest physicist, who would later become the best-known and most influential member of the human rights movement in the Soviet Union, you will be more than impressed today by the almost word-for-word correlation between the main points of his Razmyshleniya and those of Gorbachev’s reform programme. Moreover, Sakharov’s essay would also provide a conceptual basis for the emerging civic movement by linking the concept of human rights, which was quite present in the public awareness, with the global challenges of the time. Sakharov’s Razmyshleniya lent new meaning to work on behalf of human rights by transferring it out of the realm of the merely empirical into that of ideology. Sakharov recognised the key feature of the civic movement of the 1960s: its significance as society’s reaction to the postponement of modernisation, which had failed to take place in the post-war period, and was then undertaken only in a half-hearted and unbalanced way under Khrushchev.

Once this essay had appeared, the concept of human rights was no longer merely an aide for moral orientation; it had taken on a new character (not only for Russia, but for the whole world), that of political philosophy. Razmyshleniya appeared in April of that year, 1968, undoubtedly influenced by the events unfolding in the country and abroad.

Finally, another event occurred, almost simultaneously, one that completed the consolidation of aprotest milieu: the first issue of the Khronika tekushchikh sobytii (Chronicle of Current Events), a typewritten bulletin written by human rights advocates and the first and only samizdat newspaper. The date the first Khronika came out, 30 April 1968, can be seen as the day the human rights movement in the U.S.S.R. completed its development. Over a period of 15 years (1968-82), the Khronika was the undisputed backbone of the movement.

The term “backbone” applies to the Khronika in several respects. First, with the launch of the Khronika, the dissidents’ world took on a temporal dimension. Until then, the public consciousness had been unable to reflect upon the preceding period in categories of historical time, because resistance against imminent evil that was motivated by existential fear does not recognise categories of that kind. Many of those who were inclined to describe that evil in political terms – by identifying it, for example, with the Soviet regime, Communism, Stalinism, etc. – understood their resistance as a moral, or even aesthetic issue, one that precluded a historical perspective. If that were so, what kind of ‘chronicle’ could there have been? And what kind of “events”?

What influenced what? Did the name of the bulletin alter the world view of the human rights defenders, or on the contrary, did the name chosen for the bulletin reflect a change in their world view that had already occurred? It is hard to find an answer to that question today. Regardless, the Khronika provided a temporal axis, along which the future events in the world of Soviet dissent could be plotted. It also conferred an additional significance to every individual act of resistance, that of being a moment in the history of the dissidents; it forged the image – probably a mistaken one – of the human rights movement.

Along with the acquisition of a temporal perspective, the human rights movement owed its first progress in building an internal structure to the Khronika. Vladimir Lenin was right once again when he pointed out that an underground paper – admittedly, he was referring to a different one – was “… not only a collective agitator and a collective propagandist, but also a collective organiser”. The bulletin, usually with an initial “circulation run” of 10 to 12 copies (also known as nulevaya zakladka [roughly, “zero generation manuscript”]), spread throughout the country in hundreds of typewritten copies. The traditional samizdat mechanism functioned effectively: the number of issues in circulation increased through the process of distribution. At the same time – and this feature was seen for the first time with that publication – the many lines used to distribute each new issue began to work in the opposite direction as well, functioning as channels for gathering and conveying back information for future issues. This system of reader feedback specific to the Khronika and as far as we know, unique within the Soviet samizdat was laconically described in the Khronika itself in its fifth issue, dated 31 December 1968:

… [A]nyone who is interested in ensuring that the Soviet public is informed about events occurring in the country may easily submit information to the Khronika. Give your information to the person from whom you received the Khronika. That person will pass it on to the person he received the Khronika from, and so on.

The system of multiple, branching lines that had built up around the Khronika, based on personal relationships at first, appears to have been the proto-structure of the dissident community. It was of extreme importance that this system, which was initially restricted to certain large cities (Moscow, Tbilisi, Novosibirsk, Riga, Tallinn, Vilnius, Nizhny Novgorod [formerly Gorky], Odessa), quickly spread to encompass all of the large cities in the Soviet Union. Every new place named on the bulletin’s pages meant a new permanent correspondent, or at least a temporary one.

How many potential protesters were there in the Soviet Union by 1968? What were the resources that a protest movement to come would have at its disposal?

According to data collected by Andrei Amalrik, a total of 738 persons signed the various petitions in support of Ginzburg, Galanskov, Dobrovolsky and Lashkova. Of course, that figure takes into account only those protests that were publicly known. Amalrik conducted a sociological analysis of the composition of the signers: 45 per cent were scientists, 22 per cent people engaged in the arts and 13 per cent engineers or technicians. In view of the country’s enormous size, 738 people was a mere handful. However a significant fraction of that small group, which had begun to perceive itself as a community, came from the intellectual elite. One should not be misled by the fact that at the beginning of the campaign the protesters expressed themselves in highly loyal terms – in the form of petitions addressed to party and government bodies. Most of those who had appended their signatures to open letters in support of the four “heretics” were well-aware that they were committing a disloyal act, impermissible for a Soviet citizen. The repressions that started in the spring of 1968 – people being fired, expelled from the party, etc. – proved that the regime also considered such acts to be disloyal. It didn’t have another choice as the breeze of the Prague Spring was stirring in people’s minds, and if the Kremlin had let the signers go unpunished – or, heaven help them, made concessions to their demands – it would have faced not hundreds, but thousands or tens of thousands of protesters in the next campaign, possibly even on the streets and squares instead of just on paper. In fact, the Moscow “epistolary revolution” of 1968, which, by the way, also affected a number of other cities, constituted an open quarrel between the regime and the liberal-minded intelligentsia. The latter was now fully conscious of what it had earlier only suspected: for one, they, the intelligentsia, disapproved of the political regime in the country, and for another, that regime was, in ideological terms, alien and even hostile to the intelligentsia. Moreover, that hostility was not elicited by one ideological position or another adopted by certain intellectuals; the regime evinced an allergic reaction to all independent types, including Marxist-Leninist, of thinking. This was now understood by those who protested as well as by those who considered protest futile or too dangerous. In any case, it became clear that the protests were eliciting a significant response in society, even though they would bring no practical results, and that the protesters, despite their relatively small numbers, could expect sympathy and the direct or indirect support of social groups of the population that played an important role in the country’s life.

How can one describe the conceptual basis of the opposition in 1968? To reduce it to two phrases, the political concept can be described as “anti-Stalinism” in a broad sense, and the world view was one based on the concept of human rights, freshly rediscovered by the Soviet intelligentsia in the years 1965-67. As a result, a few years later the protest movement that emerged in 1968 came to be called the human rights movement. As to the infrastructure of the emerging movement, the samizdat had successfully taken over that function.

God is not alone in knowing precisely what resources were available for protest: to put it bluntly, when it came to exerting real influence on politics, there were next to none. But as limited as they were, those resources had one very important characteristic: They were renewable. After the initial wave of repressions had swept over the signers, the choice became simpler. Either you refrained completely from any kind of civic activity, or you joined the ranks of the “heretics” (the term “dissident” was not in use yet) and faced all the sad consequences for your career and biography that this choice entailed. Naturally, the majority – not without some moral suffering – chose the first option, but quite a large minority decided to retain a position of resistance. In the years following, the repressions drove those who were most prominent and most active out of the dissident community. More were washed away by the wave of (partly forced) emigration of 1970-72. But nonetheless, right through to the beginning of the 1980s, the circles of dissident activity were constantly replenished by a permanent influx of new volunteers, new enthusiasts.

This did not become obvious until autumn, after the first wave of protests and repressions had passed its peak.

The finale of “Moscow 1968”, the fateful night of 20-21 August that put an end to the Prague Spring, produced a tremendous psychological fissure in the souls of several generations of the Soviet intelligentsia. Many years later a group of young people conducted a kind of sociological survey on the subject “What does 21 August mean to you?”. They received a wide variety of responses, but there was nonetheless one feature common to all: all of respondents were able to remember precisely where and how they spent every minute and hour of that day. This rare phenomenon of collective individual memory occurs only at the turning point of an era. In Russia people remember only three other twentieth-century dates in this way: 22 June 1941 (the beginning of the war); 9 May 1945 (Victory Day) and 5 March 1953 (Stalin’s death). It is interesting that the public did not perceive the much bloodier suppression of the revolution in Budapest in November 1956 with that level of tragic intensity. That event was not perceived as the end of an era. This fact testifies to the remarkable evolution undergone by the civic mentality between 1956 and 1968.

The most dramatic reaction to the events was a demonstration conducted by eight citizens (including the two authors of the Petition to the World Public) at noon on 25 August on Moscow’s Red Square. That desperate act, which was motivated by personal moral considerations that were essentially not political at all, became both the ultimate expression and the conclusion of the entire period of consolidation of the protest movement in the U.S.S.R. It set a pattern for dissident activity that remained in place for years to come and at the same time, put the final stroke on the era of the rise of civic protest. From this moment on it was clear: civic protest as a mass phenomenon did not exist. The numerically small, but highly determined community that continued to exist after August 1968 as the sober remains of the “epistolary revolution”, which was soon to be called the human rights movement, was founded on the idea of civic protest as an existentialist act, one not burdened with any political connotations. This situation continued into the mid-1970s. The human rights movement in those years remained a subject of cultural rather than political history.

The story of the human rights movement does not end in August 1968, but a discussion of its further evolution, the history of its institutions, society’s response to it, etc. is beyond the scope of this article.

First published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation EU Regional Office Brussels, May 2008. Edited by Nora Farik.