Anthropocentrism causes political injustice and ecological destruction. But an inverted anthropocentrism, in which the nonhuman is granted rights, is not the solution. Only by redefining the human can democracy be about the conditions of shared life.

That both the planet and democracy are in peril seems obvious. Indeed, though their crises operate at different scales and tempos, they are nonetheless increasingly linked. As John Keane argues in his essay on how democracies die, the destruction of planetary life is not only the slowest form of democide, but also the most worrying.

Particularly when the effects, say of climate change, are catastrophic, they open doors for normalized emergency rule, unraveled democratic subjects, fearful populations, and persistently unequal distributions of harm.

What was once posited by philosophers like Hannah Arendt as the relatively autonomous space of the political – the space within which democratic actors and institutions appear – has been well and truly breached by the ecological. Less obvious, perhaps, is how each crisis is connected to a deeply rooted, hydra-headed anthropocentrism.

Slash-and-burn forest clearing along the Xingu River, Brazil. Image: Image Science & Analysis Laboratory, NASA Johnson Space Center. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Neither as simple as a presumed human moral superiority above all other living things, nor as straightforward as a master narrative that explains them both, anthropocentric ideas and practices nonetheless matter greatly in both the crisis of democracy and the crisis of the planet.

I believe that the way forward lies not in a democracy in which greater representation and rights are extended to nonhuman nature, even though, as Keane documents in his essay, such experiments are well underway around the world.

Rather, we need to develop a wider conception and practice of politics, as a process engaged with the nonhuman world, which in turn intersects human aspirations to create more just political institutions.

What 20th century democracies pursued as technical and extractive in relation to nature and to humans within nature, needs to be pursued in the 21st century as a properly political relation – that is, as an involved form of interaction over the conditions of shared life.

Forms of anthropocentrism

Anthropocentrism is most commonly employed around arguments about who or what is a morally considerable subject. For environmental ethicists such as Val Plumwood, Eric Katz and Katie McShane, it is a critique of drawing this line at the species boundary of the human, and opens up possibilities for ecocentric, biocentric, or assemblage-driven forms of moral consideration. For others, such as Luc Ferry, it is marshaled as a humanistic defense of that boundary, paradoxically also signaling the incompleteness of humanism as a political project.But more than a question of moral consideration, which in turn might affect democratic decision-making or other related practices, anthropocentrism has constituted the political in at least two further ways, both of which matter for thinking about the future of democracy in a planetary context.

The first is captured in contemporary territorial state sovereignty, a vision that became fully global by the mid-20th century. This presumes nature solely in instrumental terms as a resource for human use, never as an end in itself. This reduction of nature to a ‘standing reserve’ is not just a matter of extractive corporate power overrunning more respectful, sustainable, local relations with nature; it is also enshrined in the international state system. This is often the case even in contemporary international environmental law, such as the Convention on Biological Diversity, which guarantees states the sovereign right to own and use nature on their sovereign territories.

Bound up with distributional justice questions between countries of the global north and south over who gets to benefit from nature’s use in relation to which histories, the Convention itself posits a formal equality between states that belies a deep inequality in informal practice. Nonetheless, it captures an essential anthropocentric quality of state-led extractivism and geopolitics – one shared by democratic, autocratic, socialist, and postcolonial regimes alike over the past two centuries.

This instrumental, practical anthropocentrism has been a condition of growing human freedom and prosperity globally in the 20th century, as Dipesh Chakrabarty has pointed out. Conversely, as Jairus Victor Grove has noted, it was a significant component of a Euro-American global war machine of the past few centuries (and in more recent decades, Asia and other centers of global power), with planetary repercussions.

In a second sense, anthropocentrism has mattered to politics because it has told a story about the human – a story that is putatively universal, but in practice deeply partial, and connected to exclusions along raced, gendered, colonial lines, among others. In this guise, as I’ve argued previously:

what anthropocentrism takes most for granted is not the superiority of the human over the nonhuman, but rather that we know what the ‘anthropo’ is and that ‘human’ is a fixed, unchanging category of reference. For those who are not quite ‘human’ at any given moment – such as animalized prisoners at Guantanamo, those in concentration camps in Auschwitz who were rendered as ‘bare life’ or the state-of-nature natives who appeared in the conquering of the New World – it has been abundantly clear that ‘humanity’ is not simply a biological species reference, but a political category, and one that need not pay heed to species itself.

These two kinds of anthropocentrism have mattered, in variable ways, for what democracy is in its many variations, including in its current state of turbulence around the world.

The dual force of an exclusionary conception of humanism and the human, combined with an arrogant assumption of the human species’ superiority over nature, has been devastating. As a result, Keane is right to point out that not only is the planetary crisis causing problems for democracy, but also that there are important experiments afoot in all sorts of domains, extending democratic formations across the human-nonhuman divide.

Limitations of the ecological demos

Rights for nature are cropping up in New Zealand, Ecuador, India, and elsewhere – though they are perhaps better understood as one half of a political settlement with indigenous collective personhood and/or sacred deities of major religions, and have had mixed effects. Animal rights have been around as a category of protection for decades, and are growing; indigenous guardianship relations as joint sovereignty experiments – enshrined everywhere from UNESCO World Heritage to national law – bring a new politics of place, stewardship, and care into play.

In one sense, many of these political innovations do involve a procedural turn towards considering a broader range of interests within human democratic deliberative procedures. Robyn Eckersley has called this the ‘all-affected principle’, whereby those affected by a harm should be included in procedures to deal with it, with whatever accommodations are appropriate. Taken at their word, they might represent an important modulation of democratic practice into more ecological modes, via a greened and transnational form of state and geopolitics that remains yoked to, and emphasizes, democratic principles.

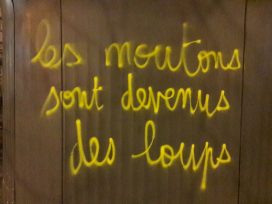

At the same time, this general turn to an ecological demos could well be read as a peculiarly inverted anthropocentrism, which confuses the exclusion of nature from moral and political life with a maneuver to incorporate nonhuman life further into human political circuits.

As the Canadian naturalist John Livingston wrote in the last century about the question of rights for redwood trees in the United States: ‘How bloody patronizing! How patriarchal for that matter. How imperialistic. To extend or bestow or recognize rights to nature would be, in effect, to domesticate all of nature – to subsume it into the human political apparatus.’

This resonates with Miller’s critique that democracy is people-bound and thus should own its anthropocentrism, in whatever ways it evolves to meet planetary politics, rather than trying to elect representatives for nature – even if Miller far too glibly imagines asking people to choose between saving ecosystems or serving human interests. (The point is that those questions are no longer fully separable, at least if earth systems science around planetary boundaries and its relation to human flourishing is any guide.) Still, Miller, like Livingston, is right to point out the poverty of political imagination at work in extending current categories of liberal democratic practice – rights, representation, interests – to nonhuman life.

A new definition of the human

Instead of extending the demos to nonhuman nature, as a presumed solution, the way forward for our planet and democracy is to acknowledge nature’s own, different political modalities, by recognizing interspecies politics.

Some more specificity around the politics of the planetary might help. For example, climate change does not equal the totality of the planetary, by a long shot. It is a peculiar, if not shocking narcissistic effect of anthropocentrism that the planetary issue we seem most focused on (climate change) is the precisely the one that (some) humans directly caused, and (some) can most directly fix. Its nonhuman impacts are vast, and yet little noticed by most.

The solution to this is not necessarily ‘broadened demos’ or ‘expanded listening’ (which ‘smart nature’ devices might even claim to accentuate). These continue to presume a singular plane of politics that is essentially human. Instead, we need to take a different route against anthropocentrism.

First, the anthropos in anthropocentric democracy and politics needs to be rethought and differently institutionalized in democratic life. The ‘human’ must be understood less as a bounded, solely rational liberal subject, and more as an ecologically embedded being, interconnected with nature in ways both helpful and harmful. Recent events have made this case but need to be emphasized: we are entangled with viruses and microplastics, but also with microbial relations and relations with place.

We need a revised conception of ‘the human’, one that is ecologically situated, but also prepared to condone some instrumental uses of nonhuman nature: as the thing that has carried global living standards forward, and that freedom has depended on (as Dipesh Chakrabarty has noted).

But equally, we must be willing to explore how living well with others on earth can become a shared political project that engages both humans and nonhumans. We must recognize and refine the political quality of the relations that democratic states – and other states – can develop with nonhuman life, including its effects on other humans. The anthropocentrism of democracy rests in its blindness to the political qualities of most of the natural world. It is a relation more closely resembling the thin, opaque, unequal and sometimes unshared frameworks of international relations, rather than those of domestic politics.

This is a Third Politics aimed neither at democracy within states, nor at global scales of greening great power struggle or projects for inclusive cosmopolitan tolerance. It is a politics about the conditions of shared life, in which instrumental interactions rest alongside qualified relations. It is a politics devoid neither of force and violence, nor of stable relationships, mutuality and accommodation.

It calls for seeing contemporary projects for human democracy as simultaneously encountering and confronting a world of other political formations. It is new iteration of geo-politics, one taking the ‘geo’ seriously and centrally; and one in which neither the territoriality nor the nature of states can be assumed.

Rethinking nature

Can democracy mutate successfully in this environment?

Central to actually-existing democracies in recent centuries has been an assumption about the existence of a stable territory or ground and a relatively stable or at least slowly moving nature. Both are patently changing. The mobility of nature is a challenge to democratic institutions, though less so to extractivist capital, which is quite used to chasing after the next big thing. It is also a challenge to a humanity that, while mobile in many ways, tends to live life in relatively rooted paths and routes.

It is democracy’s capacity to deal with mobility – human, plant, animal, biological, geological – that is at issue, as much as experiments around the human-nonhuman divide.If democracy is to survive and evolve – and there is no reason to think it cannot – it must be both less anthropocentric, and more open to its ecological embeddedness.

Published 12 April 2023

Original in English

First published by Public Seminar

Contributed by Public Seminar © Rafi Youatt / Public Seminar

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- Living dead democracy

- Why Parliaments?

- Spelling out a law for nature

- No more turning a blind eye

- The end of Tunisia’s spring?

- Protecting nature, empowering people

- Albania: Obstructed democracy

- Romania: Propaganda into votes

- The myth of sudden death

- Hungary: From housing justice to municipal opposition

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Four months into Trump’s second term and the president’s ICE raids on immigrants, triggering protests in Los Angeles now under troop surveillance, prove that ‘democracy is under assault’. Could a historic courtroom reprimand provide the necessary guidance for a moral reset?

Since the collapse of Novi Sad’s train station in November, student-led protests have erupted across Serbia, inspiring a nationwide movement against corruption.