In January 2018 LinkedIn published its first ever Economic Graph report. These reports provide a picture of the job market and thus identify the different labour needs to be met in various regions of Europe. Following this particular report’s publication, LinkedIn and the European Commission (EC) held a meeting at the European Parliament on 22 May 2018. Bringing together European and national parliamentarians, as well as a number of stakeholders, the meeting set out to reflect on how to improve cooperation between the public and private sectors so as to reduce the widening gap between the supply of available training and the demands of the labour market.

Two issues firmly on the table in this discussion were the implementation of public policies that would promote better dialogue between education systems and employers, and the training of tomorrow’s ‘new talent’ to meet the changing needs of the labour market. The consensus at the end of the meeting could be summed up as follows: in a world where innovation and technological progress, particularly in terms of digitization, are constantly transforming what constitutes ‘human capital’, the education and training of ‘talent’ must go beyond the rigidity of the education provided by an undergraduate degree, and as such must promote the acquisition of skills that will enable students to adapt to the needs of the labour market. Despite differences between the language used by the EC and that used by LinkedIn, both sides shared a perspective grounded in two axioms: first, that there is a gap to be bridged between the supply of available training and the demands of the labour market; and, second, that we need public policies that encourage education systems to provide future workers with the skills that will enable them to adapt to continual changes in the market.

This LinkedIn and EC meeting coincided with publication by the Council of the European Union of a ‘Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning’. In it, the Council updated the list of competences it had detailed in its 2006 recommendation, and emphasized the importance of acquiring competences in the field of ‘science, technology, engineering, and mathematics’, as well as those related to digital technologies at ‘all stages of education and training’.

Taking as its starting point this latest Council of the European Union document, which lists the key skills required for employability, this article draws also on ongoing work in the sociology of education, to examine the ideological roots of the EC’s concern over the gap between available higher-education-level training and labour market needs in the European context. In doing so, it analyses the EC’s discourse on lifelong learning and looks back on milestones in the emergence of mechanisms for tailoring education systems to suit the labour market. More broadly, this analysis will reflect on the paradoxical nature of those neoliberal policies that aim to bridge the gap between university education and the economic sphere.

The Lisbon Strategy

Tailoring the training provided by higher education institutions to suit the needs of the labour market is in no way a new preoccupation. As early as the Middle Ages, universities were torn between the mission of providing students with a professional education in law and medicine, and that of imparting knowledge of a more general nature, divided between the trivium (grammar, rhetoric and logic) and the quadrivium (music, arithmetic, geometry and astronomy).

Although this tension between educating and training a qualified workforce and imparting reflective knowledge is inherent to university institutions, neoliberal policies on higher education have since the 1980s favoured the first of these endeavours, leaving the second by the wayside. What’s more, as numerous sociological works have shown, the wave of neoliberal policies that gained momentum in the 1990s all involved reducing public subsidies and, in several industrialized countries, resulted in the privatization of institutions and increased tuition fees. As I will go on to explain, these developments have only exacerbated the problem.

At the European level, the neoliberal university reform movement has been in action since 1999, when the Bologna Declaration was signed by twenty-nine countries. The resulting Bologna Process, to which the signatories committed, refers to a harmonizing of the European higher education system and the establishment of a European Higher Education Area (EHEA). As an emerging ‘knowledge economy’ began to shape the nature of global competition, the Bologna Process aimed first and foremost to strengthen European higher education systems by promoting a specifically culture-based ‘European university model’. The EHEA project took on a new dimension when it was integrated into the Lisbon Strategy in March 2000, the goal of which was to make Europe ‘the most competitive and dynamic knowledge-based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion’.

The adoption of the Lisbon Strategy saw the EC take over the steering of the Bologna Process, using the Open Method of Coordination (OMC). The EC continues to organize regular conferences, during which the ministers of education in signatory countries agree on a series of tools to be put in place to achieve the process’s objectives.

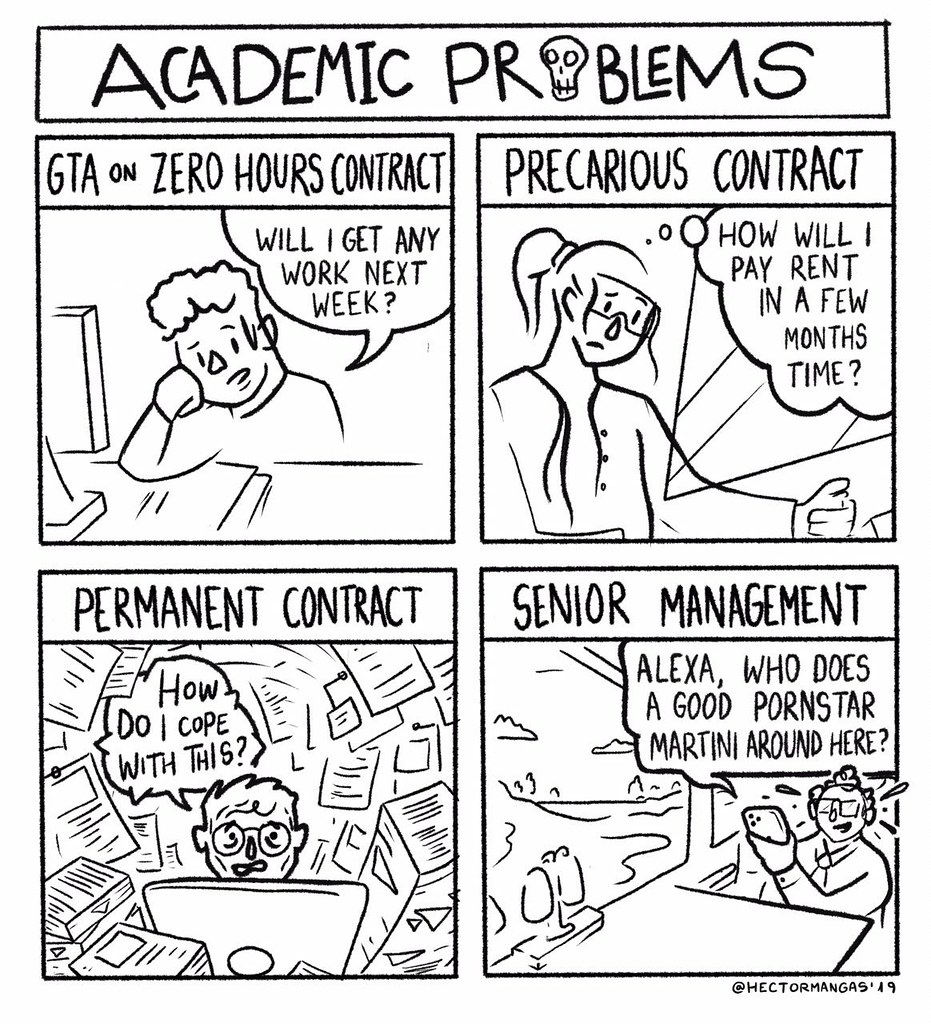

Academic Problems by Héctor Mangas #UCUStrike @hectormangas #PornstarMartini 🍸

Photo by Dunk from Flickr

In the years following the adoption of the Lisbon Strategy, these tools, which helped harmonize education systems, were implemented in national legislation across Europe. In turn, governments aligned their graduation cycles to the bachelor’s-master’s-doctorate model, set up an agency for monitoring European quality standards in higher education, and introduced into their curricula the European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS), which allocates credit according to learning outcomes. With the EC playing a coordinating role, the signatory countries have thus provided the EHEA project with a workable mechanism for achieving the objectives of the Lisbon Strategy, stimulating employment and strengthening the European economy.

Lifelong Learning

The creation of the EHEA and the incorporation of its tools in national legislation has relied on a legitimating discourse anchored in a concept of ‘lifelong learning’. In October 2000, the EC adopted a Memorandum on Lifelong Learning, in which it clarified the role to be played by education systems in meeting Lisbon Strategy objectives. This document, which is part of the European Employment Strategy, adopted by the European Council as early as 1997, calls on member states to make lifelong learning the pillar of a strategic framework for tailoring their education systems to suit constantly changing socio-economic demands:

Lifelong learning is no longer just one aspect of education and training; it must become the guiding principle for provision and participation across the full continuum of learning contexts. The coming decade must see the implementation [sic] of this vision. All those living in Europe, without exception, should have equal opportunities to adjust to the demands of social and economic change and to participate actively in the shaping of Europe’s future.

The EC has succeeded in forging a consensus around this matter. Hybrid in nature, lifelong learning discourse brings together two seemingly contradictory views on the role that education systems play in society: though it is anchored in European documentation promoting a vision of education geared towards employment, it also conveys the idea that education involves the pursuit of accessible learning goals by people of all ages in all fields. This duality means that lifelong learning can be used to steer actors with divergent interests towards common goals.

In the French Community of Belgium, to take one example, the fusion of these two views was illustrated in the way lifelong learning was discussed by members of parliament during the debate leading up to the adoption of the Bologna decree of 2004: ‘The PS [Socialist Party] has always made clear its desire to prioritize the broadest access to higher education, and its concern both to see to it that our fellow citizens can continue learning throughout their lives and to remain open to languages and education abroad.’

The report cites Michel de Lamotte, who argues, for the first time in human history, ‘most of the skills an individual picks up at the start of their training and education will be obsolete by the end of their career’ (Tolebem 1998, 77). Two points follow from this observation. First, it sets out the limits of excellence. Second, it captures quite nicely the idea that the challenge posed by the drive towards excellence is first and foremost to learn continually. Lifelong learning, then, must contribute to, and keep up the level of, professionalism in order for education and training to be effective.

As Neyrat reminds us in the case of France, lifelong learning represents what is in fact a clean break with the notion of ‘ongoing education’, which, according to Condorcet’s philosophy, should ‘extend to all citizens’ and ‘take in the entire system of human knowledge’. In contrast to the idea that ongoing education should be guaranteed by the state through public funds, the concept of lifelong learning, like that of the socially active state, is based, in essence, on individual responsibility. As the skills that are initially acquired are made obsolete by socio-economic changes, particularly those brought about by technological progress, it falls to individuals to demonstrate their continued relevance and so remain employable. Developed and promoted by the OECD in the early 1990s, lifelong learning incorporates the postulates of the ‘human capital’ theory developed by both Theodore Schultz and Gary Becker in the early 1960s. This theory sees workers as the managers of a skill set, fed by the experiences and learning they acquire throughout their lives, that allows them to increase their value on the labour market.

Although neoliberal ideology conceives of all human activity as a potential investment in human capital, education is still the primary contributor to individuals’ employability. This contribution to the value of future graduates in the labour market is conceptualized as a private return on investment. Within this framework, the private return is considered to be greater than the public – that is, the socio-economic benefits individuals derive from their education are thought to be greater than those the state derives from income taxes or other positive external outcomes of higher education. This notion, coupled with a crisis in public finances, remains the dominant argument used by governments in the last three decades for raising university tuition fees.

Such an argument might be familiar from the work of neoliberal economist Milton Friedman of the Chicago School, who seeks to justify making students pick up the tab for their education. In his 1955 book The Role of Government in Education, Friedman proposes that public funding ought only to cover ‘compulsory education’. Any state funding of institutions, he argued, should furthermore be shared with families, who could receive education vouchers allowing them to choose their preferred school. As far as higher education is concerned, Friedman believes that the role of the state should be limited to granting loans to students, the repayment of which should be taken directly from the income of these future graduates once they enter the labour market.

The human capital and Chicago School theories converge, then, in making students themselves forge the connection between higher education and the labour market. Under the pressure of debt, students are transformed into rational agents who must evaluate the potential return on their education. To ensure that future graduates are employable, governments will accompany this debt burden with measures that give students more freedom to build a curriculum tailored to labour market needs. Framed sometimes as a matter of student needs, the fostering of success or the promotion of interdisciplinarity, this flexibilization of curricula often results in the division of programmes, or the academic year, into modules based on learning outcomes and ECTS credits. As well as breaking up academic cohorts, this process erodes the coherence of programmes based on a more theoretically oriented teaching of a discipline. Coupled with the obsolescence of prior education, this modularization and breaking of disciplinary traditions results in a fragmentation of academic knowledge.

In their narrow approach to addressing unemployment rates, politicians have forgotten that a gap between higher education and the business world is a condition for maintaining the autonomy that higher education institutions need in order to further the production and transmission of academic knowledge. Autonomous, publicly financed institutions offer university professors and researchers the environment in which to produce and impart critical and synthetic thought. The fall-off in public subsidies to institutions makes them yet more dependent on private funding, which rather than representing any altruistic gesture brings with it a number of strings. Private sector influence is reflected in the rising number of seats given to companies by educational institutions on their boards of directors. In the field of research, dependence on private subsidies not only leads to the prioritization of funding for projects that meet the ‘innovation’ needs of business and industry but also has harmful effects on the conditions governing publication of research results and on public access to them. Meanwhile, this inhibition of academic freedom sacrifices the process of innovation needed if we are to find solutions to such contemporary issues as climate change and growing social inequality.

Photo by UNclimatechange from Flickr

Towards a neoliberal anthropology of the gap

Policies aimed at strengthening the relationship between the world of higher education and the labour market, while having spread and intensified over the past two decades, are part of a more general movement, dating to the 1970s, towards the shaping of a neoliberal society that fundamentally abhors unproductivity. As Pierre Bourdieu wrote, the propagation of neoliberal doxa is the result of a process of domination by economic theories and their infiltration within all areas of social activity. Although this neoliberal doxa did not translate into public policy until the 1980s, it was forged as a societal project in the late 1930s. In 1938, while observing the rise of Communism and Fascism, several internationally renowned economists, such as Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig von Mises and Wilhelm Röpke, met in Paris for the Walter Lippmann Colloquium to renew the foundations of liberalism.

In his lectures at the Collège de France in 1978 and 1979, Michel Foucault noted that neoliberalism breaks with the liberal vision of a market as a natural phenomenon. Despite the ideological differences among participants in the Walter Lippmann Colloquium, a consensus developed around the idea that the state should actively facilitate competition and put in place rules that would improve institutions’ ability to adapt to the needs of the market. Governance, then, was no longer a question of distinguishing legitimate areas in which the state should or should not intervene but rather of regulating policy based on the functioning of the market.

As Foucault put it:

The market economy does not take something away from government. Rather, it indicates, it constitutes the general index in which one must place the rule for defining all governmental action. One must govern for the market, rather than because of the market. To that extent you can see that the relationship defined by eighteenth century liberalism is completely reversed.

In this reversal to which Foucault refers, all social institutions, educational ones included, are called upon to operate in line with the market. Schultz and Becker’s theories of human capital thus lead us to consider each human activity as a potential investment in the growth of individual productivity. This transposition of economic values to all spheres of social activity is the culmination of the construction of the neoliberal subject, homo economicus, in which everyone is their own entrepreneur.

This article was original published in La Revue nouvelle 3/2021.

It is in this context, in which all social activities are included in the calculation of economic profit, that we must understand the aversion shown by neoliberals to the gaps that remain between the labour market and university education. In their view, since social institutions must submit to the dogma of economic performance, every space of activity not occupied by the market represents a loss in the efficiency of public investment in the education system.

This tendency, under neoliberalism, towards an inability to grasp that educational institutions can offer opportunities that do not lead to immediate employment raises questions about the capacity of societies to sustain spaces dedicated to autonomous creative activity. Here we see a paradox for defenders of neoliberalism – a system that is, in theory, founded on the principle of freedom.

Translated and edited by Cadenza Academic Translations