Meat is not a necessity

Does the comfort of the quarantined consumer outweigh the life and safety of the slaughterhouse workers who cannot afford to stay home? The recent coronavirus outbreaks in meat processing plants pose a dreadful question.

The culture war around eating meat the north Atlantic way is a backlash against warnings that mass dairy and meat production contribute hugely to climate change – and many other forms of environmental destruction. The evidence has been around for a long time: CO2 and methane emissions on the one hand, industrial cruelty on the other, have motivated people to reduce their consumption of problem products. And with the few jolly vegans – and yes, sometimes smug vegans – came anger in return.

Adaption of a photo by schaengel from Pixabay

Meat is a symbol of welfare. The more of it one chugs, the higher one’s status. It’s also an important part of our cultural identities – from the thousands of types of cured meats that characterize Europe, to showing off masculinity in steak culture. Vienna, where I’m writing this editorial, is most commonly known for its schnitzels.

In a notorious Hungarian joke, a college student visits their grandparents and tries to come out to them as gay. But, they ask, do you still eat meat? Yes. Alright then.

Confrontation with cultures that don’t eat pork has been a recurring theme in French state schools, who have refused to offer other options to their Muslim pupils. And hoaxes about Islamization have frequently warned that our sausages will soon be taken away. In his latest article, Péter Krekó explains why conspiracy theories such as this soar in the information vacuum, and how they are often exploited to legitimize violence.

Going meatless has long been a delicate subject that even dedicated environmentalists have tried to avoid, or approach with care. But as green politics has grown in importance, along came the growth of the industry of meatless alternatives – met with angry resistance.

Far-right politicians have spoken up against eating insects1 and for many, the glory of a big old chunk of flesh has become a symbol of the conservative lifestyle. But the experience of a rich meal is also a status symbol for working class and lower-income people. Coronavirus is striking down specifically on them, as they are securing easy access to meat.

While some had the luxury to stay at home and slowly lose their minds homeschooling and e-meeting, millions have lost their jobs, or rather their shifts, working outside of regular employment. Others were told to be happy to have work, although without appropriate protection. One big problem area in Europa and in the US has been the meat industry.

Meat processing is likely to be underpaid labour in hard conditions. The food industry is dominated by irregular employment and is often staffed by extremely vulnerable migrant workers. The cold and damp environment, lack of sunlight and thorough ventilation make these places perfect nests for a respiratory infection. The crammed line work and the demand for speed and expediency during long shifts guarantee that an infection like COVID-19 can wash over plants like Tönnies.

The working conditions in these factories were already a problem before corona. Now it’s straight-up dangerous. Right now, in western Europe and in the US, meat factories are the hosts of the biggest outbreaks – beside prisons.

What sets this problem apart from the horror of healthcare being overwhelmed, or grocery workers being exposed, is that meat is not essential. It may be important to us, but it’s very possible to live without it. Unlike water, electricity or waste removal, quarantine would have been bearable even without frankfurters – or, God forbid, wieners.

Which industries get to endanger their workers is a political decision. The outbreaks in the meat industry are a result of disregarding people’s safety unnecessarily.

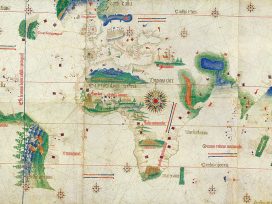

It is the same disregard that informs – or systematically uninforms – the reluctance to address the climate catastrophe. Or as Daniel Pelletier and Maximillian Probst put it: the biggest story ever. Malcom Ferdinand argues that this ignorance for the people who are deemed less important – manifested most obviously in colonialism and slavery – is at the root of the ecological devastation of our age, and have been for over six centuries. In an interview for Revue Projet, Ferdinand points out that environmentalism is often viewed as something championed by white people.

To use this window of opportunity that the forced slowing down that corona has brought, one must include the viewpoints of those who have been – and are still being – used and exploited to sustain a global supply chain. Their needs, demands and knowledge are not obstacles, but the guide to developing a new relationship to the earth that sustains us – and could nurture many more of us well.

Eurozine has launched a new focal point, Overdue: The ecology of humans, to address the cultural and political factors behind this delayed response to the ecological crisis, and to explore potential ways out of it.

This editorial is part of our 12/2020 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 29 June 2020

Original in English

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Trump’s imperial ambitions are forcing the EU to rethink its global position. And European far-right parties, swollen on fears of diminishing world power, are paradoxically flogging the ethnic nation as a place of shelter. But finding unity in scapegoating migrants blatantly fails to recognize the need for a common purpose in times of worldwide uncertainty.

Excitement over ‘rare’ elements

Julie Klinger in conversation with Misha Glenny

The race for green transition supplies is on. But where’s the thrill in metals, discreet and hidden yet widespread? Mining, intensive due to low concentrations, throws up waste elements like arsenic. Space cowboys and deep-sea dredgers contest environmental stability more than China’s monopoly, based on 40-years of involved processing. Health and recycling regulations are a must.