Armenia: Light in the dark?

Since the Russian war on Ukraine, post-revolutionary Armenia has been turning towards the West in search of security. But how is the new situation impacting domestically on the vulnerable South Caucasus nation? Is Armenia’s democratic light in the region as bright as some would believe?

After the Russian invasion of Ukraine, almost all former Soviet states are now faced with an existential challenge. Armenia may be one of the countries most at risk: not only does it face the possibility of Russian neo-imperialist expansion, it is also mired in an ongoing conflict with neighbouring Azerbaijan and Turkey over the unresolved status of the Nagorno-Karabakh region, known to Armenians as the Republic of Artsakh.

With few resources to rely on, Armenia’s status as what the Biden administration refers to as a ‘bright spot’ (defined as ‘a political juncture that opens the clear possibility of near-term substantial improvement in the state of democracy in a country’) is one of the few reliable levers it can pull to attract the attention of the international community.

Even by today’s standards of global turmoil, Armenia’s situation is dramatic. Since 2018, the country has seen two national elections, a constitutional transition, a peaceful revolution, attempts at reform, a pandemic, a full-scale war, an attempted coup and recurring border skirmishes. The war in Ukraine has exacerbated the difficult choices that Armenia is facing. But it is the Armenian population of Nagorno-Karabakh that remains in most danger.

The roots of the dispute over the region go back to the 1920s, when the Soviet Union assigned it to the Azerbaijani SSR, despite it being overwhelmingly inhabited by ethnic Armenians. In 1988 the majority Armenian population of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region demanded that it be transferred to Armenia. Baku obviously did not agree and, after the USSR collapsed in 1991, the conflict escalated into to a full-blown war. This resulted in the self-proclaimed Republic of Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh) gaining de facto independence and taking control of surrounding Azerbaijani territories. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians and Azerbaijanis became refugees and IDPs, including Armenians from Azerbaijan and Azerbaijanis from Armenia, Nagorno-Karabakh and surrounding Azerbaijani territories.

In the war of 2020, Azerbaijan regained possession of the territories around the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region, as well as the city of Shushi and the district of Hadrut inside Nagorno-Karabakh itself. At the time of writing, the Lachin Corridor, the sole remaining access route from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh, is controlled by the Azerbaijani government. It was first blocked on 12 December 2022 by Azerbaijani protesters, who claimed to be environmental activists but appeared to be acting on behalf of Baku. On 22 April, the Azerbaijani military went further and installed a roadblock on the Lachin road near the border with Armenia. The Russian peacekeepers deployed to the region in 2020 to supposedly ensure the functioning of the Lachin road are turning a blind eye.

Many observers, both in Armenia and abroad, warn that the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh are at imminent risk of ethnic cleansing, as Azerbaijan tries to force Armenians out of the region, either by continuing the blockade or through military action. A decision by the International Court of Justice demanding that Baku lift its blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh has failed to produce any results.

However, 2022 also created new opportunities for Armenia. Russia’s failures in Ukraine and the West’s more active involvement in eastern Europe have given the country a chance to overcome its neo-colonial dependence on Russia. In this context, Armenia’s democracy has become a foreign policy asset. However, Russia continues to command the metaphorical heights in Armenia’s security sector and economy, while the Azerbaijani military literally commands the heights inside the territory of Republic of Armenia. Russian president Vladimir Putin and his Azerbaijani counterpart Ilham Aliyev both remain in a position to inflict significant harm on Armenia, endangering its nascent and fragile democracy.

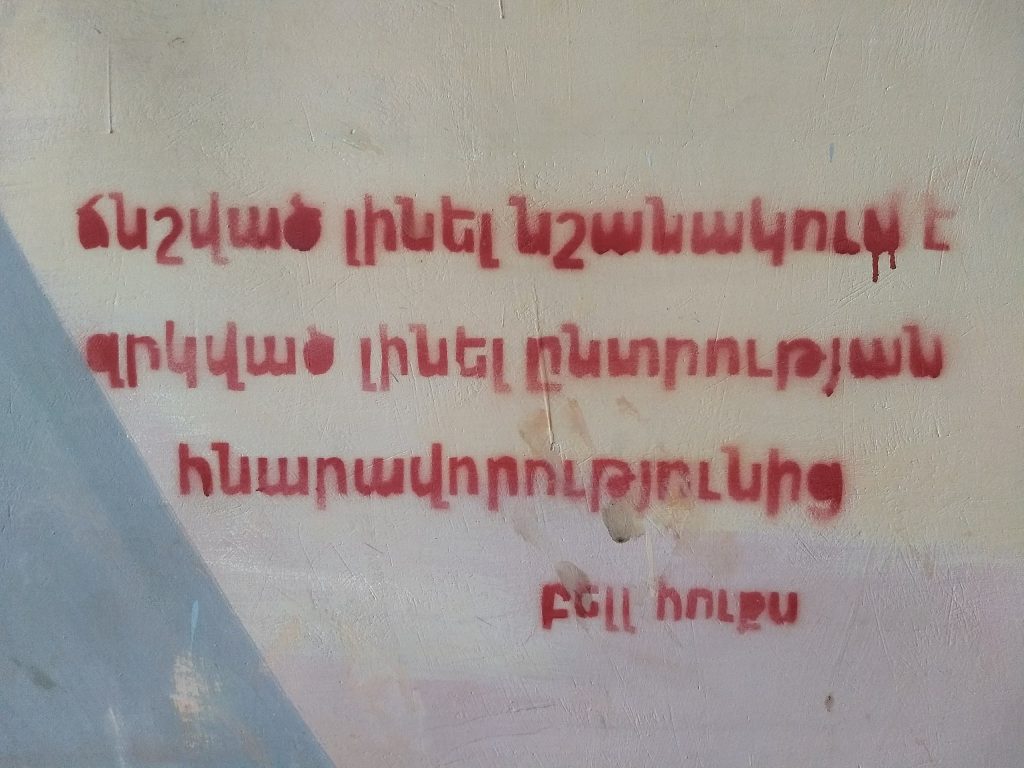

Graffiti on the streets of Yerevan in 2018. ‘To be oppressed means to be deprived of your ability to choose. (bell hooks)’. Image: RaffiKojian Wikimedia Commons

Time of trials

‘The ‘Velvet Revolution’ of 2018, which overthrew Armenia’s corrupt authoritarian elites, was welcomed with euphoria in the country. Armenians pinned their hopes on the new government, led by the former journalist and political prisoner Nikol Pashinyan. But things were about to take a darker turn. First came the global COVID-19 pandemic, which brought deaths, lockdown, logistical difficulties and a collapse in economic activity. However, the horrors of the pandemic faded in comparison with the large-scale war with Azerbaijan that broke out in September 2020 in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The hopes that Armenian society and the country’s elites had pinned on Russia in terms of security guarantees did not materialise. When Baku launched a full-scale attack on Nagorno-Karabakh, with Turkey providing support Russia remained neutral. Armenia had little chance. On 9 November 2020, after 44 days of war in which more than 4,000 Armenian servicemen lost their lives, Pashinyan signed a trilateral treaty with the presidents of Russia and Azerbaijan, ending the war on conditions that were extremely unfavourable for Armenia. Russian peacekeepers were stationed on the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, while the only road linking the region to the outside world, the Lachin Corridor, was placed under Russian control.

Though the 9 November agreement ended full-scale hostilities, it marked the beginning of a new series of trials for Armenia, both internal and external. The country found itself threatened by a new military escalation from Azerbaijan, while domestically the defeat led to a political crisis. Eventually, the impasse was resolved by new elections in 2021. Supporters of the pre-revolutionary government, led by former presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, received about a quarter of the vote and seats in parliament. This would have been unimaginable immediately after the Velvet Revolution. The surge in popularity stemmed from the military defeat in 2020 rather than from any nostalgia for the pre-revolutionary order. However, Pashinyan’s party Civil Contract was still able to secure a parliamentary majority, since above all else most Armenians feared the return of the pre-revolutionary status quo.

Most importantly, the election was considered free and fair by international and local monitors. Even the losers accepted these results, something that had rarely happened in pre-revolutionary Armenia. Though severely weakened by the defeat of 2020, Pashinyan and his team vowed to push forward with the democratic reform agenda of the Velvet Revolution. When it came to foreign policy and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, they advanced ‘an agenda of peace’, promising to try to find a solution to the conflict and a blueprint for co-existence with their eastern neighbours. The elections of 2021 showed that democratic procedures could restore stability in the beleaguered country and resolve a seemingly intractable internal political crisis. However, the difficulties facing Armenia remained overwhelming.

A beleaguered nation

The situation became worse still when Russia launched its attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022. The most heated topic of debate in Armenia is the question that many post-Soviet countries are now facing in one form or another: how can they ensure their survival as an independent nations? But while most post-Soviet countries are attempting to find a balance between Russia and the West, the situation in Armenia is more complicated. Apart from the threat of Russian neo-imperialism, it also has to deal with aggression from Azerbaijan and its Turkish backer. Finally, to add a further complexity to the situation, Russia remains Armenia’s main trading partner and energy supplier. Indeed, an increase in trade with Russia and the influx of middle-class Russians fleeing the Putin regime mean that Armenia is experiencing an unprecedented economic boom, with the economy growing by a staggering 12.6 % in 2022.

Various political forces have positioned themselves in different ways on these issues. Before the war in Ukraine, the opposition claimed that the solution to Armenia’s conundrum lay in closer cooperation with Russia. They blamed the defeat in 2020 on Pashinyan’s inability to find common ground with Putin. They could, they claimed, rebuild relations with Russia if the Armenian prime minister was removed. This position seemed plausible to many in the immediate aftermath of the 2020 war but has become increasingly less so in the post-February 2022 context. Now that Russia is toxic in the international arena and has failed to achieve its objectives in Ukraine, Moscow’s reliance on Azerbaijan and especially Turkeyis growing. It is becoming clear that closer cooperation with Russia could bring serious risks: Moscow is now even more willing to sacrifice Armenian interests to preserve the loyalty of Aliyev and Erdogan.

Meanwhile, as the West consolidates in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the bloc’s leaders are proclaiming the defence of democracies around the world to be their new agenda. It therefore seems that new opportunities are opening up for Armenia, which is now able to position itself as one of those ‘democratic bright spots’ in an authoritarian neighbourhood. The strengthening of the West’s position in the post-Soviet space has emboldened non-parliamentary parties and civil society groups, which have been suggesting a pro-western shift in Armenia’s foreign policy for years but were never taken seriously. The parliamentary opposition remains decidedly pro-Russian, but even Pashinyan’s critics have had to admit that Moscow’s position in the region has weakened. The government is therefore seeking a balance in its foreign policy that would allow it to reorient the country towards the West without provoking a destructive response from Russia.

Obviously, a lot depends on the outcome of the war in Ukraine: both victory and defeat for Putin could have terrifying consequences for Armenians. Had Putin been able to achieve his initial goal of occupying Ukraine and turning it into a client state, Armenia would have been forced to join the USSR 2.0, whatever the form envisaged by the Kremlin, along with other post-Soviet countries. Weeks before the invasion of Ukraine, the Belarusian leader Alexander Lukashenka had said that a new ‘union of sovereign states’ under Moscow’s leadership would be created, and that Armenia ‘has nowhere else to go’. Given that Lukashenka is Putin’s closest ally and had probably been aware of some of Kremlin’s plans, many in Armenia were alarmed. Today, this scenario seems unlikely.

But a Russian defeat could also spell danger for Armenia, since Yerevan is still heavily dependent on Russia for its defence and Azerbaijan and Turkey could use the resulting security vacuum to attack Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh. Russia’s failure has allowed Azerbaijan to adopt a more hawkish stance on Nagorno-Karabakh and other issues, such as the delineation of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Baku has opted for ‘salami tactics’, applying pressure on Armenia and especially Nagorno-Karabakh, forcing small concessions and, when Armenia has resisted, using military force. The Russian peacekeeping force in Nagorno-Karabakh has failed to prevent these incidents, lest Moscow spoil its relations with Baku.

The opening up of regional communications is another source of tension. With Moscow’s tacit support, Baku is demanding the creation of a Russian-administered extra-territorial transport corridor that would connect ‘mainland’ Azerbaijan with the exclave of Nakhchivan. Not only would the ‘Zangezur Corridor’ give Azerbaijan access to Nakhchivan via Armenia, removing the need for the detour through Iran that it currently uses, it would also jeopardise Armenia’s link to Iran. For Armenia, ceding control over the road to Iran would be another step towards a loss of sovereignty. Yerevan has therefore mounted resistance, finding unequivocal support from Tehran, whose position on the ‘corridor’ somewhat surprisingly aligns with that of the West.

Moving away from Moscow

Arguably, it was the influence of the West that prevented a new large-scale war in 2022, when on 13 September the Azerbaijani military launched a massive offensive on the Republic of Armenia’s internationally recognized borders. The fighting, which according to official sources claimed the lives of 200 Armenian soldiers and 80 Azerbaijanis, was stopped thanks to decisive diplomatic intervention from the international community, particularly the US and France.

The West condemned the offensive, however Russia and the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) – Armenia’s supposed allies – failed not just to offer military help, but even to state its disapproval of Azerbaijan’s actions. Instead, Russian and CSTO officials reproduced Baku’s narrative that because the borders between Armenia and Azerbaijan remained undefined, it was impossible to say that an attack on Armenian territory had taken place. This ignored that Armenian cities and villages far from the border had been heavily targeted during the fighting, including the tourist city Jermuk, known for its mineral water, and the village Artanish on the shore of lake Sevan.

The Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, visited Armenia in the immediate aftermath. Having visited both Kyiv and Taiwan earlier in the year, Pelosi expressed support for Armenian democracy and referred to closer cooperation between the US and Armenia. In October, in an EU-brokered meeting between Aliyev and Pashinyan, both sides confirmed their mutual recognition of the borders of 1991. This outcome was heavily criticized by Pashinyan’s critics as ‘a sellout’ to Azerbaijan, however the government’s position is that talking about ‘the rights and security’ of Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh rather than independence allows room for diplomatic interpretation. It was decided that an EU monitoring mission would be sent to the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, though Azerbaijan later rejected the presence of the mission on its territory.

The West’s reaction to the September escalation, Pelosi’s visit and the arrival of EU civilian experts on the Armenian side of the border all signal a major geopolitical shift in Armenian foreign policy. Finally, Armenia seems to have an alternative to its alliance with Russia, which has increasingly come to look like a form of neo-colonial dependence. Russia has reacted nervously to these steps, particularly the arrival of the monitoring mission.

Yerevan, however, has continued to distance itself from Moscow. Russian politicians and propagandists, including Margarita Simonyan, the head of Russia’s state-run media agency RT and an ethnic Armenian, were barred from entering the country. On 24 March 2023, a few days after the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, Armenia’s constitutional court finally cleared the way for the ratification of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the ICC. If the Armenian parliament goes ahead with ratification, this will create an even bigger rift with Russia.

A complete and immediate break with Moscow could have dangerous consequences, however. Russia continues to exercise disproportionate influence over Armenia, especially in security and the economy. The severance of all political relations with Russia is therefore unlikely.

The Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, who have been living under an Azerbaijani-imposed blockade since December 2022, are meanwhile hostages to both Russia and Azerbaijan. They believe that the only thing stopping Azerbaijan from implementing a campaign of ethnic cleansing is the presence of the Russian peacekeeping force. More and more Armenians now think that the only way to save their brothers and sisters in Nagorno-Karabakh is the direct involvement of the international community. This would entail replacing the Russian peacekeepers with an international mission that has a powerful mandate, preferably from the UN. Again, however, this is an unlikely prospect. Russia is reluctant to abandon its position in the region and the West does not seem inclined to go beyond statements and resolutions.

Is democracy here to stay?

The fact that democracy seems to be becoming Armenia’s selling point in international relations raises an important question: how genuine is Armenia’s democratic transformation? After all, the world is full of democratic transitions gone wrong. So, is Armenia’s status as a ‘democratic bright spot’ simply a public relations tool employed by the Armenian government to secure support from the West, or is it a true reflection of reality?

This issue is a matter of heated debate in Armenia. The opinion of the pro-Russian opposition is clear: Pashinyan is a dangerous populist and Armenia is a dictatorship disguised as a democracy. This is proven, they say, by the criminal cases against former presidents Kocharyan and Sargsyan, as well as some of their supporters. Such accusations need to be taken with a grain of salt, to say the least, since both Kocharyan and Sargsyan were the leaders of a corrupt regime and most of their supporters enjoyed positions of power and wealth in that system. On the other end of the scale, civil society and media criticise the Pashinyan government for not doing enough to bring pre-revolutionary officials to justice for the crimes they allegedly committed while in power. A common criticism levelled at the government by civil society, activists and independent media is that it failed to pursue a lustration policy after the revolution, and that consequently many mid-level officials have kept their positions.

It is difficult to deny, however, that systemic corruption has been dealt a serious blow. According to international watchdogs, Armenia has recorded significant progress in fighting corruption since 2018. In 2022, Armenia ranked 63rd out of 180 countries in the Corruption Perception Index (CPI), scoring 46 out of 100. Before 2018 corruption was seen as part of the natural order of things and officials made no attempt to hide their wealth, on the contrary; they were rarely dismissed for corruption-related cases, let alone prosecuted. It was no secret that members of the government had close ties to big business and the criminal underworld, which is still the norm in some post-Soviet countries. Today, accusations of corruption against members of Pashinyan’s team often end in dismissal and criminal investigations, something unimaginable under the previous regime.

Another common criticism of Pashinyan’s government concerns the slow pace of reform in the judiciary. While there have been some changes, Pashinyan’s government did not opt for the radical solutions offered by some activists and CSOs, such as a comprehensive vetting of judges. This has enabled the system to keep going, however it has also led to a situation in which society continues to distrust the courts. The case of judge Mnatsakan Martirosyan illustrates the degree of this problem. The Supreme Judicial Council, a body that oversees the courts, appointed Martirosyan chairman of Yerevan’s Court of General Jurisdiction in January 2023. Before the revolution, the judge was notorious for making politically motivated decisions, including passing a ‘guilty’ verdict on Pashinyan himself for his participation in the protests that ended in clashes with government forces in 2008. That Pashinyan should award an important promotion to a judge who had once made him a political prisoner raised eyebrows in civil society. However Pashinyan’s supporters cite cases like this as a proof that, unlike its predecessors, the current government is genuinely committed to the independence of the judiciary.

The Pashinyan government is also criticised for the slow pace of change in the police and security sector. In December 2022 the police, rescue and immigration various services were brought together under the auspices of the newly established interior ministry. This has been seen as a positive development, since the responsible minister will answer to parliament, unlike the former chief of police, who reported directly to the prime minister. In a reform partially modelled on the example set in Georgia, a police patrol service was introduced in 2021 and set to be completed in 2023. However, watchdog NGOs see the introduction of police patrols as an isolated move rather than a part of a grand reform. Many Armenians still complain of police incompetence, and even cases of police brutality. The latest example of that came when a SWAT team raided the popular dance club in Yerevan in search of drugs, assaulting patrons and club workers, yet failing to produce any significant evidence of dealing.

As for Armenia’s National Security Service (NSS), it remains an all-too powerful body, much like the other heirs to the KGB in the post-Soviet world. In the context of Armenia’s western shift, there has been plenty of debate about the influence allegedly wielded by the Russian secret services over Armenia’s security apparatus. It was probably for this reason that in December 2022 parliament adopted a law on the creation of a Foreign Intelligence Agency separate from the National Security Service (though the new body is yet to be formed).

Yet despite the lack of reforms, it is hard not to notice the change in the behaviour of the Armenian police and the NSS. Cases involving the torture, unlawful detention and other mistreatment of citizens have dropped significantly since the revolution; and when such cases do happen, they usually lead to a public outcry and criminal investigations. This is not so much a result of institutional reforms, as the new social and political atmosphere in the country: state institutions are now under close scrutiny from the media and civil society, and the government is taking care not to damage its democratic credentials. Though the change is obvious, then, it is also easily reversible.

One of the groups most disappointed in the Pashinyan regime is the country’s environmental and urban activists. Before the revolution, protests in support of green and urban conservation issues were very common. However, after 2018, economic development often took precedence over considerations of environmental protection and urban heritage. While the public control over government and business in these spheres has increased, there have been well-publicised cases in which profits have been prioritised (e.g. the controversial funding of the Amulsar gold mine and the destruction of the historical Firdousi neighbourhood in central Yerevan).

Given these controversial trends, it is hard to give a straightforward assessment of Armenia’s post-revolutionary development. On the one hand, there has been clear progress in human rights and democracy. On the other, many of the reforms have been too slow or have stalled completely, leading to disappointment among supporters of the revolution. But although Armenia’s democratic reinvigoration may not have met the expectations of all its citizens, it is impressive compared to the record of other countries in the larger neighbourhood – the post-Soviet space, eastern Europe and the Middle East. Of Armenia’s immediate neighbours, the only democracy is Georgia, and even progress there has stalled, according to independent watchdogs and local civil society groups. Established democracies like Hungary, Poland and Turkey have long been sliding towards authoritarianism, while autocratic regimes such as Russia, Iran and Azerbaijan have consolidated and hardened. So, while Armenia’s democratic achievements may be modest, when seen against the background of darker trends in the region, Armenia is indeed a ‘bright spot’.

A favourable comparison

One of the most obvious testaments to Armenia’s democratic progress is the experience of the vast numbers of Russian migrants who have arrived in the country since February 2020. Many used Armenia as a staging post en route to Georgia or the EU, but about 110,000 are estimated to have stayed. Some of these migrants were motivated by purely economic concerns, such as the decision of their companies to relocate, but many were motivated by the desire to escape the increasingly brutal Russian regime and a war being waged in their name.

Many of these new arrivals have expressed admiration for the atmosphere of freedom in their new home. When anti-government protests were held in central Yerevan in the spring of 2022, many Russian migrants took pictures of the protesters’ tents and posted them on social media, accompanied by with captions like ‘Protests last for days and the police don’t arrest or beat up anybody’. The ‘kind Armenian policeman’ has become a meme among Russian migrants, who are used to the harsh treatment from law enforcement officials in their own country. ‘Once a policeman said something to me. First I was scared, because in Russia you don’t want to mess with the police’, said Olga, a Russian human rights activists who has relocated to Armenia, ‘then I realised he was offering me a biscuit.’

While offering biscuits to unknown women would probably be considered a breach of police ethics in a developed democracy, this story is nonetheless a sign of how different Armenia has become from its authoritarian neighbours. The question is: how far-reaching and sustainable will these changes ultimately be?

Published 2 May 2023

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Mikayel Zolyan / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

- Living dead democracy

- Why Parliaments?

- Spelling out a law for nature

- No more turning a blind eye

- The end of Tunisia’s spring?

- Protecting nature, empowering people

- Albania: Obstructed democracy

- Romania: Propaganda into votes

- The myth of sudden death

- Hungary: From housing justice to municipal opposition

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Europe turns east

Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine

Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine has put eastern Europe firmly at the centre of the EU’s foreign policy agenda and given fresh impetus to reforms by candidates for EU membership. But with rightwing movements gaining ground, support for Ukraine and EU enlargement is under threat.

Flooded earth

Osteuropa 1–2/2023

What the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam means for water supplies, agriculture and industry in south-east Ukraine. Also: Azerbaijan’s ethnic cleansing in Nagorno-Karabakh; and a profile of imprisoned Russian oppositionist Vladimir Kara-Murza.