Eastern European intellectuals, writers and artists certainly contributed to some degree to the collapse of the totalitarian Soviet system. Their ideas circulated in the public space, their courage was a model for many. In general, intellectuals, fickle, often using abstruse language, can easily become the laughing stock of their societies, but the likes of Vaclav Havel or Leszek Kolakowski were certainly not ridiculous. Of course, it was not ideas alone that undid totalitarian oppression, but they were an important ingredient in a vast array of means and modes of action.

It’s a sad paradox that now, while they, intellectuals and writers, face a united Europe, the European Union driven by free market economies and democratic principles – although at this moment undergoing a serious crisis –, the Europe they saw in their dreams, projects and aspirations, and for the members of whose parliament they could freely vote in recent years, they are probably more helpless than before, in the old times. Apparently it was in some respects easier to fight against the Central Committee than against big numb Numbers, the dark sides of capitalism and sombre nationalistic strivings.

In my country – but similar things are happening or may happen, or are about to happen in other European countries – we’re now witnessing a dangerous phenomenon. A nationalistic, xenophobic grouping is claiming the need to defend “traditional values” against the anonymous forces of “modernity”, and a parallel need to defend what’s “local” against what comes from abroad; it is trying to change the current of modern history and in doing so disregards the law, the constitution, the decency of political standards. A profound chasm divides society, which is slowly finding itself a prisoner in the cage of a more and more pervasive police surveillance.

Those who study the history of ideas and history of art know well how ancient is the struggle against “modernity”. Ancient, sometimes fascinating, sometimes noble, often well motivated and well argued. Paradoxically, what we call European Modernism, a powerful artistic movement that has changed the way we look at art and the way we read books and listen to music – simply, the way we think –, was deeply marked by growing unease with the changing face of the visible and invisible world. The pioneers of this movement were for the most part critical of the Europe that had started to emerge from the fumes of the Industrial Revolution (and from the “liberal revolution”). There are dozens of examples. Eugène Delacroix, the painter who opened the way to yet another revolution, this time an aesthetic one, to Impressionism and many other -isms, was deeply nostalgic about the disappearing beauty of the old Europe. In his wonderful Journal, which shows him to be an eminent writer, Delacroix expresses his sadness and indignation at the sight of steamships and railroads (still, he didn’t push his distaste so far as to avoid riding trains – something that is quite typical for critics of modernity). What he admired was the sight of sailing ships that, with their huge white wings, were moving slowly on the green ocean.

John Ruskin saw contemporary civilization in a similar way. Paul Valéry defended the value of the pre-industrial world and work: “Adieu, travaux infiniment lents” said he, admiring the slowness of those who had built the cathedrals, and it sounded like a prayer. And Rainer Maria Rilke hated what he perceived as the ugly modernity of Paris – as opposed to the “old Paris” devastated by baron Haussmann. But not just the ugliness of the buildings (which we now admire), but also the unpoetic quality of urban life itself. T.S. Eliot, in his famous Waste Land, erected an epitaph for modernity – but modernity survived this and many other attempts to bury it alive.

It’s actually easier to mention some of the great writers who welcomed the advent of the new world; they were not that many. Among them Marcel Proust, who admired aeroplanes and was struck by wonder at the sounds in a new sensational invention, the telephone, which allowed him to hear from the distance the voices of those he loved, the voice of his grandmother. James Joyce, too, had no qualms concerning modernity. But Yeats, his great compatriot, did and his qualms are extremely interesting.

I must confess that I understand very well some of the arguments put forward by the defenders of “old Europe” – though certainly not all of them. It’s a highly complex battle of ideas, which cannot be reduced to a simple formula along the lines of “progress versus reaction” or “Enlightenment versus Middle Ages”. It’s a clash of ideas that cannot be ignored, even now, if only because it has inspired several generations of writers and artists, has shaped our sensibilities. I can follow the arguments of those who lament the dwindling of the religious impulse, the diminishing of the imagination, the tendency to see human beings as purely biological entities (body! body! the soul is a fiction!). I wouldn’t approve though a wholesale rejection of the heritage of Enlightenment. It looks as if we, Europeans, are permanently unable to harmonize the two major components of our experience, that of the day and that of the night, that of commonsensical action and that of ecstatic poetry.

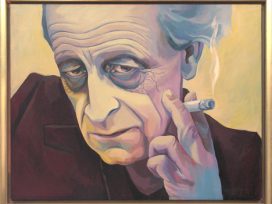

I remember reading years ago an essay by Czeslaw Milosz praising the book The Disinherited Mind by Erich Heller, an emigré German critic who fled the Nazis and taught for years at an American university (the Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois). The Disinherited Mind is of course not the only book to deal with the weakening of the metaphysical impulse in European literature (Heller’s examples were taken mostly from the German tradition), but it is one of the most inspiring to do so. It’s probably difficult to find a serious poet (except maybe the very young ones who simply prefer sheer irony to any other intellectual modality) who wouldn’t be moved by this book or wouldn’t at least become deeply interested in it. Provided that someone is still reading The Disinherited Mind.

These debates are quite old, we tend sometimes to regard them as belonging to a bygone era. And yet, an attentive reader, an attentive art lover will agree that there still exists a peculiar tension between what’s new in our civilization, the newness that strengthens the “rational” dimension of life – and can have the most beneficial pragmatic influence on our condition – and the “old beauty”, the Delacroix-like regret, the Rilke-like longing for the archaic, the Valéry-like attachment to some elements of the European tradition.

Here I can easily imagine hearing a possible critical response: what’s the weight of this elitist nostalgia against the rush of innovation, what’s the power of a sentimental epiphany against a new generation of software or stunning medical progress? Not much, indeed, in terms of what can be calculated; but the malaise, a deficit of certain imponderables, can persist for a long time. And, if we change the terms of the conversation, it’s not just the struggle between democracy and a dream of some kind of return to the past. It’s something that runs deeper, that cannot be expressed in numbers, and yet it’s there.

Any actual political or economic threat, and there are so many of them right now, makes us forget these more subtle things. Still, they don’t forget us.

But this is one thing, the debate between minds, between artists and philosophers. This debate, this tension, this fever gave rise to great poems, essays, paintings and symphonies. We still somehow inhabit this old debate – though less and less consciously. A different thing happens when politicians, practitioners, party functionaries and attorneys, and finally even police officers and informers try to enforce an ideological position. The passage between ideas and action in the real world is a most delicate one, here is the old European – and not only European – wound. And also a theme for great writers to reflect upon, to dramatize. Dostoyevsky for instance, who in The Brothers Karamazov showed us at least two levels of human reality and discourse; the intellectual convictions of someone like Ivan Fyodorovich Karamazov, who reads and reasons, affirms and doubts; and then the primitive behaviour of a Pavel Fyodorovitch Smerdyakov, whose comportment is a shadow of Ivan’s ideas.

Recently I’ve been observing with dismay attempts to effectuate this passage from projects and half-baked ideas to political reality in my own country. On the surface it looks like an innocent operation: there are people who say “our tradition is threatened”. By what? By modernity of course. Our “national identity” is threatened (is it?). By what? By modernity, by all kinds of soulless tendencies, by the emancipation of different minorities. By what’s “foreign” – as if almost everything happening these days were not “foreign”. By “the West”. We are, they say, a pious nation and we run the danger of being contaminated by godless countries.

We knew that these tendencies existed and were expressed in some obscure publications. A political party which had suffered defeats in several elections, many priests (not all of them, to be sure), some journalists and maybe three philosophers were attacking the open society that since 1989 had gradually replaced the communist system. But now that these ideologues have become ministers and their private radical right-wing convictions have been raised to the level of raison d’état, the nature of the game has changed completely. Suddenly we can see the unpleasant face of a democracy that has lost its bearings. What do you do when a populist sect wins the general election as a consequence of skilful brainwashing? Skilful and successful because it also alludes to an old, pre-war cleavage between the “socialist” and “nationalistic” halves of society, and feeds on real economic issues. So far, there are still mechanisms that secure our personal freedom, the principle of free speech is still there. But slowly, almost imperceptibly, the nature of the state is undergoing a change.

In place of a modern state that’s flexible and not free from scepticism (a scepticism well motivated by recent history), we now face a state with philosophical and theological ambitions. And this is the worst that can happen. A state cannot and ought not to philosophize. It cannot read Descartes, cannot grasp Kant’s double-edged vision. It would be hilarious and terrifying at the same time to imagine a state living what the German critics call die Kant-Krise, so deeply experienced by Heinrich Kleist for instance (as described by Günter Blamberger in his excellent Kleist book): a moment of nihilistic revolt, of deepest doubt. But the opposite situation would be equally terrifying: a state undergoing a spasmodic mystical revelation, an epiphany that would deliver the answers to all major questions. A state is not a saint Teresa of Avila. States don’t think and don’t weep. They don’t pray. They do not participate in philosophical seminars.

Charles Taylor, a well known Canadian philosopher, remarks in his Sources of the Self that in our time the following distribution of ideas and influences prevails: in our collective life, in the part of our existence which overlaps with the forces and rules of societal or administrative organization, we seem to obey the guidelines of the Enlightenment but in the private sphere, in the after hours so to speak, in our inner monologues and fantasies we rather turn to Romantic models.

This order shouldn’t be reversed.