Unheimlich: the word has a sinister ring – not least because of Freud’s famous essay of 1919, “The Uncanny” – an undertone that I always thought everyone could pick up, perhaps even without any grasp of German. Straightaway, it seems to create associations with occult phenomena, ghosts, spirit doubles (Doppelgänger, from the German), elementals and other apparitions from folklore. In my own case, the word instantly makes me think of, for instance, the encounter between Dante and Virgil in the first Canto of the Inferno, the scenes featuring the apparition in Hamlet (oddly enough, Freud didn’t rate these as unheimlich), Goethe’s “Erlkönig”, Victor Hugo’s “La chanson du spectre” and Jonas Lie’s “Kvernkallen” (a short story that the Norwegian author published in the early 1890s):

Mentre ch’i’ ruvinava in basso loco.

dinanzi alli occhi mi si fu offerto

chi per lungo silenzio parea fioco.

[While I tumbled into the depths/ there appeared before my eyes someone/ almost voiceless as though from a long silence]

What, has this thing appear’d again tonight? […]

In the same figure, like the King that’s dead.

Mein Sohn, was birgst du so bang dein Gesicht? –

Siehst, Vater, du den Erlkönig nicht?

Je suis la morte, dit-elle.

Cuiellez la branche de houx.

[I am she who is dead, she said / Pick me the holly branch.]

Hohoho – huhuhu

kvernen venter,

kvernen venter,

kvernen venter –

[Woo …woo …wooo / the mill awaits / the mill awaits / the mill awaits –]

In “The Uncanny”, Freud writes as if one of his tasks were to act as a kind of occult philologist. He allows a great deal of space to his reading of E.T.A. Hoffmann’s masterly, dark story Der Sandmann, and this alone suffices to make the text of critical interest. The essay has a boundless power to fascinate, which is due in the first instance to the special, focused gravitational force that it emits: “The Uncanny” pulls the reader into an animistic world populated by ghosts, phantoms and spirit doubles, where objects can come to life at any moment and people are subjected to portents of the most wondrous and terrifying kind. In the first place, Freud’s “natural explanations” are, as ever, utterly hair-raising and, anyway, the theme contributes to making the reader feel that the entire essay is best told on a dark evening by the fireplace: “The Uncanny” could be categorized as a ghost story lightly camouflaged as rational discourse, or perhaps a spiritualist séance conducted in the name of science: Freud’s role is primarily that of a shaman, discreetly seated at the head-end of the psychoanalytical couch, but actually not quite admitting that he believes in what he elicits.

The closest rendering of the essay’s key concept in Norwegian is uhyggelig (cf. Sverre Dahl’s translation) – in English, “sinister; uncanny” – but the German word is something of a translator’s conundrum. Freud is clearly very much aware of this because, quite early in the essay, he examines several European languages to find possible, if often inadequate, words that are supposedly equivalent to unheimlich, before scrutinizing his native language for shades of meaning, drawing on the German dictionaries by Daniel Sanders and the Brothers Grimm. With regard to the latter in particular, he is at least as preoccupied by what is written in the context of heimlich (homely), that is, the word meant to be opposite in meaning to unheimlich in view of its negating or revoking prefix. These lexicographic observations have consequences well beyond linguistics.

Heimlich is derived from heim/Heim [at home/ (a) home], and has an intriguing similarity, both phonetically and in its written form, to the Greek term for destiny heimarmene or Heimarmene, as it is often a personification of fate; it has important functions in stoicism and Gnosticism. Heimlich (also heimelich, heimelig), originally denoted what pertained to the home – Heim – and can, in that sense, be translated as “homely”. A variant of the word with a transferred meaning was also listed: vertraut, freundlich, zutraulich (Grimm), i.e. “confiding, friendly, trusting”; other perfectly possible versions include “comfortable” and “cosy”. In modern German, however, the sense of “homey cosiness” is contained within the words heimisch and heimatlich (also heimelig), while heimlich as of today is best translated according to what was originally its secondary meaning: “secret”, “concealed” (cf. the Grimms’ dictionary where a parallel is drawn between Geheimnis and the Latin occultus). This sense of the word implies – then, as well as now – that it is now much more difficult, or just about impossible, to make a distinction between it and its apparently negative counterpart, unheimlich; the prefix has lost the defining function and serves instead as a reinforcement. So, unheimlich can be understood as something especially heimlich. Freud’s definition of the uncanny starts at this point and his interpretation is illustrated by a quotation from Sanders’s dictionary that strongly appealed to him, and which Sander in turn quoted from the nineteenth-century writer Karl Friedrich Gutzkow’s novel Die Ritter vom Geiste (it is 3,600 pages long and I’d happily stand whoever claims to have read it all several pints of beer): “We speak of it as heimlich […]. They call it unheimlich.” In addition, Freud has noted one of Schelling’s pronouncements in Philosophie der Mythologie, which was cited by Sanders to provide another example of current usage: “Unheimlich is what one calls everything that should have remained secret, or concealed, but which has emerged into the open.” Indeed, to quote Freud’s own take on the word: “Generally, we are reminded that the word heimlich is not unequivocal but belongs to two sets of concepts which, although not each other’s opposites, are completely foreign to each other: the familiar and pleasing, and the hidden and secretive. Unheimlich can be used only as the opposite [of heimlich] in its former sense and not in the latter.”

Indeed, not only Norwegian translators struggle to find the right word to encompass the German concept. When he hit on it, Freud struck philological gold and his discovery is very hard to reproduce elsewhere. A survey of the titles given to his essay as translated into a range of languages offers us an overview of the real pitfalls and problems inherent in the task of the translators: Marie Bonaparte’s French version of das Unheimliche is l’inquiétante étrangeté (“the frightening strangeness”), while Roger Daudon has given the meaning a twist in the opposite direction with l’inquiétante familiarité (“the unsettling familiarity”). Both options are equally defensible although an amalgamation of them would have been closer to the ideal. In Spanish, Freud’s discourse is about lo ominoso (“the fateful” or “the ominous”); in Italian, the most frequent rendering is il perturbante (“the disturbing” or “the distracting”), but other variants have been suggested, such as il sinistro (“the sinister” or “the threatening”) and lo spaesamento (“the alienating”, or “the disorienting”). The Portuguese interpretation is either o estranho (“the alien”) or a inquietante estranheza, which means just about the same as Marie Bonaparte’s take on the Freudian term. The established English translation is “the uncanny”, an expression that always makes me imagine instructions on a label on “how to un-can”.

Hoffmann and the Sandman

In his review of how unheimlich is translated into other languages, Freud himself draws attention to the Greek word xenos. Although he does not analyse it further, it actually has one of the multiple meanings explored in the essay. Xenos means “strange” (and “mercenary”), but also either “host” or “guest”, and it is this final semantic dualism that also emerges in the Latin hospes and its many derivatives in Romance languages (ospite, huésped, hôte). If guest and host merge, if the homely and the alien meet, then the eponymous character in Hoffmann’s story Der unheimliche Gast could just as well be Der unheimliche Wirt, or else the prefix might be omitted to allow both to be just heimlich. Besides, all those who have paid attention to what Hoffmann has written know very well that he had a genius for playing on ambiguities – Freud, who is definitely one of the attentive readers, wrote that Hoffmann is “an author who, better than almost anyone else, succeeds in creating gruesome [unheimliche] effects” (p. 238).

Hoffmann is essential to Freud’s exploration of das Unheimliche: the account and analysis of The Sandman occupy many pages in the essay and are, to quote Harold Bloom, “unquestionably his strongest reading of any literary text”, although, as Bloom goes on to say, Freud’s approach shows a few oddities. In order to deal in more detail with the problematic aspects, I am going to follow Freud’s example and begin by outlining the plot of Hoffmann’s story, which I would obviously urge everyone to read. Freud’s report on the Sandman narrative actually demonstrates his enviable capacity for literary insight.

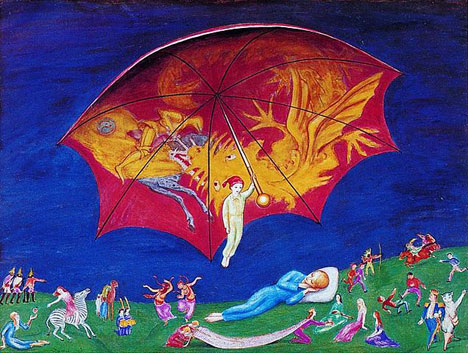

Nils Dardel (1888-1943), John Blund, 1927. Source: Wikimedia

Throughout his childhood, Hoffmann’s protagonist Nathanael was tormented – even traumatized – by his imaginings about the Sandman, the German version of the Norwegian Ole Lukkøye or Jon Blund [Ole or Jon Shut-Eye]. A series of popular comic books by Neil Gaiman is called The Sandman, but the characters and stories have remarkably little to do with the German figure. In Hoffmann’s mind, the essentially kindly spirit takes on positively demonic qualities. He describes how an old nurse convinces Nathanael that, if the Sandman finds a child who won’t go to bed, he will steal the child’s eyes to feed his own offspring (the little Sandmen usually cluster together in a nest on the Half Moon and look like peculiarly nasty birds with hooked beaks; they eat human eyes, as other young birds eat worms or insects). Nathanael gradually comes to identify the unscrupulous lawyer Coppelius with the Sandman. Coppelius often comes to the house to visit Nathanael’s father, and one evening, in a horrible sequence of events, tries to rob the boy of his eyes. His father steps in and prevents the deed but is killed shortly afterwards by an explosion in his study, an “accident” probably engineered by Coppelius. However, the lawyer has disappeared without trace. Many years later, when Nathanael is a student, he comes across a travelling Italian optician called Coppola. We soon realize that he must be the frightening creature who caused the death of Nathanael’s father. Coppola sells spyglasses and spectacles and, as eventually becomes clear, has manufactured the artificial eyes of the automaton Olimpia, a clockwork wooden doll in the shape of a woman, constructed by a professor Spalanzani, and introduced as the professor’s daughter. Nathanael, who believes her to be alive, becomes so besotted by this artificial creation that he forgets all about his own fiancée, Clara (or Klara) and tries by every means to gain the doll’s favour – a satire with touches of absurd black comedy. Then he comes across the lifeless doll with empty eye sockets and it finally dawns on him what has been going on. Spalanzani throws the automaton’s eyes on the floor and declares that Coppola has stolen them from Nathanael (who alternates between seeing them as dead objects, and aglow with “moist moonbeams”). The poor student’s response to this revelation is a complete mental breakdown followed by a long illness, but he eventually comes to his senses and is reunited with Clara. The couple climb the town hall tower in their hometown one day and Nathanael uses one of Coppola’s spyglasses to take a closer look at what Clara has described as a strange-looking “grey bush that truly seems to be advancing towards us” (Hoffmann, p. 47). The young man is gripped by madness and the story ends with his leaping from the top of the tower, an act watched by the lawyer Coppelius – he has mingled with the crowd below. It gives him an evil satisfaction before he vanishes from the scene. The last part of the story reassures readers that Clara is well, married and the mother of two sons.

As Freud points out in a footnote, the image of the father in The Sandman is split into a good being, Nathanael’s natural father, and an evil counterpart, Coppelius – a pattern that is also seen in the pair Spalanzani/Coppola. (pp. 244-5). This reflects the son’s conflicted feelings towards the father figure, an Oedipal ambivalence that can also be clearly seen in Hamlet, although in Shakespeare’s version, the absence of a sharp polarization between good and evil makes the relationship more complex. The supposedly good King Hamlet, whom we encounter only in the shape of an apparition, seems above all to be typically unheimlich (a grim warmonger who doesn’t seem to have been very agreeable in life, either) while the usurper Claudius, like Queen Gertrude, comes across as rather menschlich, allzu menschlich – “human, only too human”. This however does not to imply that Hoffman’s narrative is somehow less subtle; as the antithetical pairs in The Sandman are all father figures, there are certain difficulties about deciding where the boundaries are between them – difficulties that are further complicated by Spalanzani and Coppola jointly creating a daughter, as well as by the fact that Coppelius disappears or, in a sense, dies after the death of Nathanael’s father. The entire narrative is infused with ambivalence and lack of certainty although, at one level, the reader will not feel any doubts – as Freud emphasizes in a polemic aimed at Ernst Jentsch, whose article “Zur Psychologie des Unheimlichen” (“On the psychology of the uncanny, 1906), claims that the sensation of horror has its origin primarily in the “intellectual uncertainty” arising in encounters with something new and unknown that one is unable to get a grip on or explain in any way. The argument is based on the premise that das Unheimliche is conditional on not-knowing – on what Plato called doxa, i.e. “belief not justified by knowledge” – and that the phantoms will vanish in line with the state of not-knowing (this became a widely held view, also defended by Epicurus). In the context of art, Freud disagrees with this line of thought and writes this about the plot development in Hoffmann’s story:

It is no longer valid to speak of “intellectual uncertainty”; we know now we are not to be presented with a madman’s fantastic imaginings, behind which we, full of sober superiority, can recognize a rational reality and our impression of the uncanny [der Eindruck des Unheimlichen] is not diminished in the slightest by the explanation. Thus, intellectual uncertainty does not help us to reach an understanding of the effects of the uncanny.

(pp. 242-3)

Later in the essay, Freud actually writes that das Unheimliche in many contexts reaches its most convincing literary form if the author “for a long time does not allow us to guess the conditions he has chosen for the world he has created” (p. 266) or if, throughout the narrative, it remains unclear whether we are dealing with natural or so-called supernatural events.

He specifically says, however, that there are more opportunities for generating horror in fiction than in reality, and also that his present discussion concerns a variant of Unheimlichkeit that has its roots in rejected or primitive notions. Horror based on repressed “infantile complexes” should, according to Freud, be seen as a somewhat different proposition, a view that undeniably fits in with his idea that das Unheimliche is a result of repressed psychic matter returning. Nonetheless, the primitive mind – arguably, “belief in the supernatural” – has an essential function in Der Sandmann and Freud of course stresses in his analysis of Hoffmann that the reader’s uncertainty gradually disappears: what happens in the story is real within the framework of the fiction, and not the confabulations of a disturbed mind (unless one refuses to budge from the helpfully diffuse term “unreliable narrator”). Overall, it would seem that Freud’s opposition is not only to Jentsch, but also to Tzvetan Todorov and his definition of “fantastic literature”, made more than fifty years later (in 1970). According to Todorov, the fantastic emerges when readers are unable to make up their minds about whether events have natural or supernatural explanations: “the moment one answer is chosen rather than another, the fantastic is abandoned in favour of related genres: the strange [l’étrange] or the miraculous [le merveilleux]. The fantastic lies in the hesitation of an individual who knows nothing other than the laws of nature, but is faced by an apparently supernatural event.” This definition confuses more than it enlightens, among other reasons because several stories by writers with a known predilection for the fantastic, including Hoffmann, Gautier, Sheridan Le Fanu, Violet Paget, Blixen, Borges and Cortázar, regrettably turn out not to be “fantastic” but more suited to being categorized in one of Todorov’s other subgenres. Nor is there much hope for fantasy literature, since it only rarely allows the reader the “hesitation” critical to Todorov’s definition (in the Todorov system, the paradigmatic writer is E.A. Poe). As for Freud, he recognizes directly that das Unheimliche as a literary effect can be born out of what he regards as superstitions or illusions – strictly speaking, though, Freud’s own system is all about our illusions; in the Freudian universe, we are all no more or less than “such stuff as dreams are made on”.

Freud’s analysis of The Sandman is penetrating if at times marked by his fervent drive to make the story agree with his own psychoanalytical theories. We are told that Nathanael’s fear of having his eyes stolen is (rather predictably) rooted in a castration complex and it is admittedly striking how closely his “eye anxiety” (Freud’s concept) is linked to the death of his father, and also how the Sandman acts throughout as “disruptor of love” (p. 244). In support of his interpretation, Freud uses a powerful reference to mythology when he argues that Oedipus blinding himself was “only a moderation [Ermäßigung] of the penalty of castration, to which he would have been subjected according to the rule of punishing like with like [die Regel der Talion]” (p. 243).

This is of course a good point, although it is perhaps a bit much to insist that blinding is a more moderate punishment than castration. But, once Freud has launched that bandwagon, he is utterly unstoppable. In The Ego and the Id, he states without batting an eyelid that the fear of death and what he calls fear of conscience can both be “understood as adaptations to the fear of castration” and if he is to be taken literally, this statement insists that life itself is less valuable than the unruly organ Goethe jokingly referred to as “the Master”. While I don’t deny that some men might well have signed up to this, a naive question comes to mind: if one is to follow up this perception – that castration is fundamental to the most ancestral human dread – how come women are affected by fear of death and of conscience, and on what grounds do women fear blinding, since this too is all about castration? On the other hand, is overt fear of castration just what it appears to be or a representation of something else, such as fear of losing one’s sight? Are eyes and cock mutually interchangeable symbolic entities? Etc. A fool may well ask; as always, Freud’s eagerness to generalize is the Achilles heel of his interpretations, with regard both to literature and to dreams, but in the case of The Sandman, his partial sight has also given him an Oedipal clarity of vision. There can be no real doubt about the paralysing effect of Nathanael’s ambivalent bond to a father figure on his later relationships with women, but the most impressive part of Freud’s reading is his consistent emphasis on the way the sinister elements of the story turn out every time to be linked to secrecy and the hollowness of home comforts – to Nathanael’s childhood home, the (at first) comforting character of his father and to the fantasy about a Jon Shut-Eye-like Sandman. This is further accentuated in the sequence when Coppelius tries to secure Nathanael’s eyes and puts the boy into a red-hot stove or Herd (the German word can also be translated as “fireplace” or “hearth”): here, the archetypal centre of the home, the warm place of worship of Hestias or Vestas, has been transformed for the duration into a miniature Hell of blue flames and thick, suffocating smoke. In this cosy atmosphere, Coppelius sets about unscrewing Nathanael’s hands and feet, only to quickly put them back on again: “Soon done, soon done” (Hoffmann, p. 16) – as if the boy was an automaton or any kind of mechanical object; indeed, a possible example of what the eighteenth-century thinker Julien Offray de La Mettrie called “the human machine”. The mechanization of Nathanael alone is terrifying enough but it also provides us with an anticipatory hint of a possible kinship between him and the automaton with whom he will fall madly in love.

The words for “secret”, or “hidden”, and “home” are not only linked but were once the same word in Norwegian, too – hjemlig, and hemmelig. What goes on between the four walls of home must be concealed from outside view: “my home is my castle.” The exposure of Josef Fritzl’s misdeeds led Tor Erling Staff to pen an earnestly conciliatory comment that brought together heimlich and unheimlich with impressively unthinking precision: “They have attempted to make it comfortable and cosy, have a homely atmosphere, so that it shouldn’t feel like a rough prison – this is a home. He [Fritzl] built a fortress but tried to create a familial setting inside. It looks all right, small and low-ceilinged, but with quite some care taken about comfort.” It is pretty sensational that an undoubtedly intelligent man should produce such outrageous nonsense (worse still, such miserably badly formulated nonsense, though stylistic critique is definitely not the point in this case). It is worth reminding the defence lawyer not only that the “familial setting” entailed complete negation of liberty, violence, enforcement, incestuous sexual abuse and psychic terror of the very worst kind but also that the subjects of all that hominess – Fritzl’s daughter and the children he had forced her to bear – led claustrophobic and utterly helpless lives as inmates of a cellar lock-up and instantly fled the moment an opportunity finally came their way. All this should surely be enough to trigger the warning lights, human, ethical and legal, blinking non-stop at Staff, but if nothing else, he had better make it very clear that there are situations in which home comforts are transformed into home horrors (hjemmehygge into hjemmeuhygge). Besides, it is a fact that Norwegian words for “care” – omhu – and the ultra-nice word for “cosy” – hygge – are derived from Old Norse hugr, meaning “thought” and thus the words share their origin with the name Hugin: “In there stepped a stately Raven.” And by then it was high time to think again.

Apparitions and repetitions

Huginn is usually not seen without his companion Muninn (memory) and the two birds provide a helpful indication of how Freud defines das Unheimliche. As an unwanted memory comes along, flapping in the wind – as when something that has been repressed or put away once more manifests itself – the “homely” is given the prefix that darkens it. This is Freud’s overview of the phenomenon he is preoccupied with in the essay, an account that is formulated with crystalline clarity:

Here, it is appropriate to make two comments in which I hope to explain the essential content of this small study. In the first place: if psychoanalytical theory is correct when it states that every affect caused by emotional impulses, regardless of which, become transformed into fear by repression, a category must exist within frightening events, of which it can be shown that it is a case of something once repressed that has returned. Such a fear would be felt as the uncanny [das Unheimliche], no matter whether it was originally a species of fear or driven by another kind of affect. In the second place: if this is truly the secret nature of the uncanny [die geheime Natur des Unheimlichen], we understand that common usage allows the comfortable/homely [das Heimliche] to slip into its opposite sense, the uncanny [das Unheimliche], as this represents nothing new or strange but something that the psyche is familiar with of old but has become estranged from through the act of repression. This connection with repression also clarifies Schelling’s definition of the uncanny as something that ought to have remained hidden and has emerged. (p. 254)

Das Unheimliche is something from the past that manifests itself or haunts us; this leads us well on the way towards seeing it as – above all, perhaps – as something “ghostly”. A ghost is indeed someone who “walks again” and imitates the living in its determined hold on an extinguished existence; had the expression not already been coined, a ghost could be characterized as “the spirit that walks” (German, Wiedergänger). Freud is actually cautious about introducing phantoms into his speculations; in this context, that which arouses terror or abject fear (das Grauenhafte) has, he says, at least as important a role as das Unheimliche. On the other hand, he admits that phantoms are perhaps the most persuasive example of Unheimlichkeit, something he emphasizes indirectly through e.g. linking das Unheimliche to enigmatic repetitions and the notably repetitive (the number that occurs in the passage below is hardly there by chance: Freud was 62 on his next birthday, the year after the essay was written):

Another set of experiences allow us to recognize easily that it is only the unexpected element of repetition that can turn the otherwise harmless into something uncanny and, in situations where we would normally only speak of “a coincidence”, force upon us the idea of the fateful, the inescapable. For instance, it is of no account if, on handing coats in at the cloakroom, you receive a slip of paper with a certain number – 62, say – or if you are allocated a ship’s cabin with that number on the door. But the impression will change if both these in themselves indifferent events take place close together, so that you come to encounter the number 62 several times on the same day, and if you then begin to notice how everything that carries a number – addresses, hotel rooms, railway carriages and so on – always contains, at least as one of its parts, that very number. (p. 250)

Repetitions generate a variant of the uncanny that has been effectively explored in a sound collage by the Beatles (mainly by John Lennon, Yoko Ono and George Harrison) called Revolution 9, in which the words “number nine” are intoned again and again with a relentlessness that reinforces the insistence that this is the voice of the revolution. When someone speaks in this way, a ghost walks: “Ein Gespenst geht um in Europa – das Gespenst des Kommunismus.” As Jacques Derrida remarks in his book Specters of Marx, repetition is, as it were, part of the spectral brand, and signalled unmistakably by words such as the German Wiedergänger and the French revenant. “A specter”, Derrida tells us, “is always a revenant. One cannot control its comings and goings because it begins by coming back” (p. 32). When the ghost shows itself for the first time, is not, strictly speaking, the first time; one of the most characteristic traits of a ghost is that it has been seen before, either while it was still a living human or after it was transformed into what Samuel Johnson, in conversation with James Boswell, called “something of a shadowy being”. Recognition – also in the Aristotelian sense of anagnorisis, i.e. a combination of recognition, realization and self-awareness – is an important component of very many ghost stories. When Oedipus realizes who his real parents are and that they will show themselves again in his own children, the insight has an undeniably ghostly element, though it would obviously be out of order to categorize Sophocles’ King Oedipus as a ghost story. Freud barely mentions Hamlet in his essay and does not call the scenes with the apparition unheimlich, but the sceptic Horatio does become convinced that a phantom haunts Kronborg Castle precisely because he recognizes the dead king:

Such was the very armour he had on

When he the ambitious Norway combated.

So frown’d he once, when in an angry parle,

He smote the sledded Polacks on the ice.

(I, i: lines 60-63)

This particular phantom is unheimlich, precisely because it is so heimlich: it represents the very concept of the past returning. Just before the quoted lines, Marcellus asks “Is it not like the King?” and Horatio says “As thou art to thyself”, suggesting that everyone is an apparition of themselves, a thought that reinforces the spooky atmosphere; integrated into his remark is the dawning of an insight similar to what Thomas Carlyle, in his novel Sartor Resartus, makes the charmingly named professor Teufelsdröckh exclaim: “O Heaven, it is mysterious, it is awful to consider that we not only carry each a future Ghost within him, but are, in very deed, Ghosts!” Besides, Horatio’s terse reply alludes to the horror inherent in the conceit of the spirit double; to be like one’s self becomes a mixed pleasure if this other “self” is a physical reproduction of one’s own being: “Du Doppelgänger! Du bleicher Geselle!”

In Specters of Marx, Derrida launches – with his usual flair for inventing striking new words – the concept hauntology, which he defines as “the logic of haunting” and claims to be “not merely larger and more powerful than an ontology or a thinking of Being” and which would “harbor within itself […] eschatology and teleology” (p. 31). At a stroke, Derrida manages to include how the past is coincident both with the present and the future, the extent to which it governs us and how it can be tangible and intangible at the same time. In this way, hauntology also becomes the science of das Unheimliche, and Derrida adds a political edge to his speculations about ghosts, an edge that time has not blunted:

It is necessary to speak of the ghost, indeed to the ghost and with it, from the moment that no ethics, no politics, whether revolutionary or not, seems possible and thinkable and just, and that does not recognize, in its principle, the respect for those others who are no longer or for those others who are not yet there, presently living, whether they are already dead or not yet born. No justice – let us not say no law and once again we are not speaking here of what is just – seems possible or thinkable without the principle of some responsibility, beyond all living present, within that which disjoins the living present, before the ghosts of those who are not yet born or who are already dead, be they victims of wars, political or other kinds of violence, nationalist, racist, colonialist, sexist, or other kinds of exterminations, victims of the oppressions of capitalist imperialism or any of the forms of totalitarianism.” (pp. 15–16.)

The complicated relationships between justice, being just, and law (justice, droit and loi) are not something that I feel the need to deal with here, but what is above all relevant in the present context is, every time, Derrida’s ethically biased politicization of the ghostly and the horrible. The ghost is a manifestation of our fundamental lack of temporal freedom, our dependence on the past and our debt to it; Marxist thought, firmly anchored in the past, poses an unheimlich threat to the glorified, ahistorical arrogance of the capitalistic-neoliberal establishment – as exemplified in publications such as Francis Fukuyama’s The End of History and the Last Man (1992), which Derrida attacks in his own book. Capitalism’s ingrained rejection of Marx and Marxism illustrates, with great potency, its fear of castration, built up over time into a state of euphoric hysteria: while capitalism has now entered into its most critical stage, its defenders insist that it is more vital than it has ever been despite having to be kept alive by a weird kind of financial oxygen supply, an intervention based on the usual premise that the poor might just as well become even poorer.

Infernal homeliness

Political issues are given considerable weight in Freud’s essay “Thoughts for the time of war and death” (“Zeitgemäßes über Krieg und Tod”, 1915), but in Das Unheimliche such matters are simply not mentioned – even though one might well assume that contemporary politics would be very relevant to the way Freud shaped the ideas he presents. The essay reached the public in 1919, the year after the end of World War I. During the previous four years, atavistic notions, which had presumably been repressed until then, appeared all over the allegedly enlightened brotherhood of European nations. A not unusual mental trauma in the post-war years was linked to the fantasy that the dead soldiers would come back as ghosts. A film from that period was said to end – I haven’t seen it, only heard of it – with myriads of soldiers rising from the mass graves and marching, shoulder to shoulder, towards towns and cities. It is hard to imagine a more concrete and apocalyptic vision of phantoms returning to haunt us; the repressed has emerged in the form of human beings sacrificed for the greater glory of a barbaric civilization.

On the other hand, brave and unheroic poets such as Wilfred Owen dismiss both repression and the glorification of the realities of war. In the poem Exposure, Owen describes the exhausted soldiers who became ghosts long before anyone had shot at them or bombed them to fragments, and how they would come back home in spirit while still at the front. But even in their imaginations, there are no homes to welcome them; the houses they had lived in have become the abodes of ghosts:

Slowly our ghosts drag home: glimpsing the sunk fires, glozed

With crusted dark-red jewels; crickets jingle there;

For hours, the innocent mice rejoice: the house is theirs;

Shutters and doors, all closed: on us the doors are closed –

We turn back to our dying.

In 1940, when history looked about to repeat itself, the dead from the previous World War also began to walk again. The phantom from 1914 turns up in one of the most quietly frightening stories I have ever read, a novella by Elizabeth Bowen called The Demon Lover, a title that refers to a line in Coleridge’s Kubla Khan – in other words, to a poem written by one of the outstanding masters of horror poetry. Bowen’s theme is a sense of dark, historical guilt but she also shows us what might come about when Freudian repression is not just a mental defence mechanism but also a cover-up for something that will emerge independently of the mind. When the repressed takes on a concrete (though not tangible) shape, it becomes a ghost, an idea that exists in embryonic form in Freud’s own writing.

In Freudian summary, let us say that a ghost is someone who has been presumed dead but “walks again” and is, in some sense or other, still alive; these spectral beings behave in ways that are essentially repetitive at the same time as they represent the familiar transformed into something horrible. With the assistance of Derrida, we are able to add that the ghost is a mixture of existence and non-existence that unsettles our entire grasp of what is life and what is death. The ghost is neither alive nor dead in any recognizable way; the spectral being is there and is not, so that ontological concepts become flawed if one tries to discuss them. In his foreword to the Norwegian edition of Specters of Marx (p. 16.), Atle Kittang touches on how heimlich will become unheimlich when the ghost behaves towards us in a way described in the German and Scandinavian languages with an eloquent verb – heimsuchen, hjemsøke, i.e. “searching the home”. The ghosts come back home, to their homes and ours, such as they also do, etymologically, in the French hanter and the English “haunt”, since both originally mean to “live in”. The verbs are derived from Old Norse heimta and haim, words also found in Middle High German heime suchen – to seek someone out at home, whether with hostile or friendly intentions. Words related to the verbs include the French hameau – a small country village, a built-up area or cluster of houses – and the very well-known English word for the same thing: “hamlet”.

If etymology takes us from the village to Kronborg Castle, it also gives us a hint of the mixture of secretiveness and strangeness that characterizes so many ghost stories. In a Norwegian classic of horror and ghost literature, the P.C. Asbjørnsen story called A Christmas Eve of Old, this theme is established at once:

The wind was whistling in the old maples and lime trees outside my windows,

driving the snow along the street, and the sky was as dark

as a December sky can ever be here in Christiania.

My mood was as dark. This was Christmas Eve and the first

that I would not spend by the hearth at home.

True homeliness is beyond his reach but a heart-warming substitute is on offer from one of the narrator’s women friends, Miss Mette, who invites him to spend the evening with her and her family. He joins them in a room that is the perfect setting for ghost stories; for one thing, it has a hearth – a fireplace – that plays a central role:

A big fire is lit in the fireplace, a big, square box of a tiled stove,

And, as I stepped inside through the wide-open fire door, the flames cast a red, uncertain glow into the room. The room was very spacious and furnished in the old style, with high-backed chairs covered in Russia leather and a chaise longue of the kind made to accommodate whale-boned petticoats and polite poses. The walls were hung with oil paintings, portraits of stiff-backed ladies with powdered hair, of Oldenborger horses and other notables in full armour or red officer’s tunics.

The syntax in the first sentence is odd in that the narrator could be understood to enter the drawing room “through the wide-open fire door”; one association is with the tale of the prophet Daniel and the men in the fiery furnace, which in turn confers to the story a touch of a descent into the flames of Hell, or of a Herd like that described by Hoffmann in The Sandman. Although the infernal is so far only hinted at, and the tiled stove radiates its traditional promise of gentle comforts, the carefully crafted opening gambit confers to the whole quoted passage a sense that this Christmas Eve celebration will be “old-fashioned” in more ways than one, given the atmosphere of powdered hair and Oldenborger steeds – its most striking feature are these constant reminders of the past. A room like this is simply made for the guests to tell scary stories and so they do; the climax is old mother Skaus’s tale about Madam Evensen, who was present when the dead gathered for a church service on Christmas Night. When I was a child, the accompanying illustration was a drawing I hardly dared to glance at and now, as a proper adult, I still have to steel myself a little to look it up: Madam Evensen is hurrying out of the church and behind her, crowded into the doorway, stand the dead, deformed creatures with skull-like faces, dressed in their best clothes and with eighteenth-century-style hairdos and wigs. They are reaching out for the living women with their bony hands since, despite the urge they feel to listen to the words of God even in the grave, these walking dead are merciless. It would have been the end of Madam Evensen, if they had grabbed hold of her, as she was helpfully informed in the church by a departed neighbour. Madam Evensen follows the advice and leaves the diabolic place of worship before the end of the ceremony:

When she got out onto the church steps, she felt them tug at her coat; she let it go, left it in their clutches and hurried home as quickly as she could. She reached the door to her cottage when the clock struck one and staggered inside, so terrified that she was practically half-dead. In the morning, the people arrived at the church where her coat was lying on the steps, ripped into a thousand pieces. My mother, she had seen that coat many a time before and I believe she saw one of these pieces, too; be that as it may, it was short, pale red with hare’s skins on the front and along the hems, as was still customary even in my childhood.

The final sentence enhances the credibility of the story and amounts to a polemic directed against any sceptics. If the coat was known to exist, and if someone had seen “one of the pieces”, then the whole story must be true. The core of the narrative – an old variant or “itinerant tale”, known in many European regions – inevitably triggers a whole stream of questions: what is the meaning of the dead gathering for a church service? What kind of dead people are we talking about: those who get no rest in the grave, that is, who have been excluded from salvation and divine bliss, at least as yet? If so, in what way do these unsaved souls worship God and why be so blood-thirsty in the midst of their strange piety? How do they have access to the church? How does such a congregation of murderous phantoms slip into the house of God on Christmas Night? Surely, it is precisely at the time when we celebrate the birth of the Saviour in a church that we should be safe from such demonic beings?

Asbjørnsen’s narrative provides an outline of an alien outpost in the Christian universe, a world of shadows or an Earthly limbo in which life after death is no more than a grotesque extension of life itself, and the living subject to terrible hatred. Besides, when horror becomes manifest and serious, it is as an immediate consequence of the past returning, because Madam Evensen recognizes the minister, the woman who was once her neighbour and many others in the congregation: “all long since dead.” The pious dead are a mystery, a secret most people would rather not know, in the same way that one would prefer not to experience a home-coming of the kind Ray Bradbury tells us about in the deeply terrifying The Third Expedition, included in The Martian Chronicles. Bradbury begins a nice ghost story on an idyllic note but it ends as an intense nightmare. Here, it is worth noting that the first Norwegian edition of The Martian Chronicles (1954) was titivated with the title Kom hjem! Kom hjem! (Come home!). Such stories shockingly emphasize the shifting position of the boundary between the concepts of heimlich and unheimlich – which is why these two words can also be understood in the context of Gaston Bachelard’s writing on the “material imagination”, i.e. an imaginative or creative ability that strives in particular to drill into the fundamental components of existence:

A form of matter that the imagination cannot infuse with double meaning, likewise cannot serve as original matter psychologically. A matter that cannot create a psychological ambivalence also cannot find its poetic counterpart [double] that would allow endless transpositions. Then, double participation is necessary – participation of both desire and fear, of good and evil, a calm mingling of the white and the black – so that the material element will grip all of the soul.

The word “double”, which I might have translated as “copy” can also mean “Doppelgänger”, and implies an ambiguity worth keeping in mind. Here, the main point must always be that Bachelard’s definition allows us a glimpse of both the being who walks again – an immaterial incarnation of ambivalence – and also, implicitly, confers the status of something original on pairs of concepts such as heimlich/unheimlich. In the beginning was the homely horror and it grips your whole soul.

It is high time for me to turn back and go home. I’ll end with accounts of two of my own experiences, which very much influenced my understanding of das Unheimliche.

The essayist and the ghosts

The first story is about something that happened when I was twelve. It was either in May or early in June, a lovely, sunny early summer’s evening, when my brother Espen, some four to five years younger than me, and I went on a visit to a brother and sister who lived not far from our house. Let us call them Tomas and Lena – it makes sense because those are their real names. The children, their mother, stepfather and a well-fed, genial dog called Peik shared a pleasant house with brown-stained, wooden walls. It was on two floors, with a cellar and an attic. Our family, Espen’s and mine, lived in an almost equally upmarket house, which I never understood how we managed to afford. Still, homes were cheaper in those days.

That evening, Tomas and Lena were to be alone at home for a while. The four of us children holed up in the ground floor sitting room and played records; we had a good time and, although I’ve forgotten what we talked about, I’m positive that it wasn’t about ghosts or anything spooky at all. It follows that when we heard someone walk on the floor above us, we took it perfectly calmly, simply assuming that one or other of the grown-ups had come back home without us noticing.

But, as the footsteps continued to pace the floor without apparently going anywhere, we began to think that the person’s behaviour was distinctly odd and not at all like Tomas and Lena’s nice, efficient parents. So, we eventually got up and went upstairs. Not a soul around – that was easy enough to establish. Anyway, by then we could hear footsteps in the room below, where we had just been.

At this point, we got very uneasy. It didn’t seem reassuring in the slightest to see the bright sunshine outside, or the colourful flowers, or Peik asleep in the garden. All the same, we went back downstairs. The place was quite empty, of course – and, instantly, we heard the footsteps start up right above our heads.

I can’t remember how many times we went up and down the stairs, while the walking continued with unerring predictability at the level where we weren’t. Neither can I remember why we didn’t get round to dividing up into two groups so that both floors could be under observation at the same time, but I guess the reason was straightforward enough: none of us cared to lose the security of being in the big group. Besides, we were pretty sure by then that trying to think strategically and outsmarting this presence wouldn’t be of any use – the phantom that paced about in the house had no intention of being caught in the act. It wouldn’t allow itself to be seen until a time that suited itself. I do remember one thing, though: when we got up into the attic to investigate, unusually, the lights wouldn’t come on, for some damned reason or another.

There was one staircase leading from the ground to the first floor, and it curved sharply at one point. If you stood in the hall on the ground floor, anyone coming down the stairs would be visible at the bend. All four of us clustered in the hall, because by then the wanderer above us had become terribly active, as if it was just about to make itself manifest: we listened as the steps arrived at the top of the stairs, then how it, slowly but surely, descended, step by step, advancing towards us.

The children’s stepfather must have been in the Territorials or was likely just a keen shot; for, whatever the reason, an unloaded rifle hung on the wall in the hallway. Tomas grabbed it, aiming at the staircase, as the rest of us crowded around him – I can still hear how his voice shook when he addressed the unknown: “Stay where you are or I’ll shoot.”

The footsteps carried on regardless, reached the bend in the staircase – and ceased. Seemingly, the being faded away into thin air or stepped straight out into nothingness. I even had a sense of the footsteps leaving an echo behind them. Anyway, there was no one or nothing to be seen and the pacing stopped for good; no phantom steps were heard again that evening or at any other time afterwards.

All four of us had the same experience, none of us were in anything like a hyper-sensitive or anxious mood and the gentle summer evening had been in no way conducive to dread. While the noises continued, none of us doubted that we were hearing footsteps, although when I last spoke with Tomas several years ago, he had concluded that the sounds must have come from creaking old floorboards. He had almost certainly given in to a rational version of wishful thinking or remembering; the auditory characteristics of that kind of creaking noises are completely different from the regular paces that rang out quietly in his childhood home. Besides, such “natural” sounds don’t move in an orderly manner between floors or stop moving downstairs when they have reached a certain step. Whatever was going on that summer evening in his and Lena’s home, we mustn’t blame on the wood. I, for one, am quite unable to think of a rational explanation of what happened.

I am not, however, in a position to make that declaration about my second story. It is about something that happened to me during an episode of sleep paralysis, and I completely accept that it is a condition which scientists insist that they have investigated too thoroughly for any hint of a mystery to remain attached to it. The responsible view is that sleep paralysis occurs when the mind is conscious but the body is still asleep, so that the dreamlike states you enter into are particularly vivid, and the imbalance between mind and body leads to the characteristic sensation of being unable to move even a finger, hence the term sleep paralysis. I don’t doubt for a minute that the explanation deals with the essence of the condition but it does not exactly cover whatever the basis might be for the waking dreams with paranormal or occult content that go with the state. It is not clear, in other words, what predisposes the sleep-paralysed person to being especially prone to dream about ghosts, vampires and assorted unheimlich phantoms.

Leopardi’s moving, beautiful poem Il sogno (The Dream), which begins with an appeal to a ghost, sounds as if it has its origin in sleep paralysis:

Era il mattino, e tra le chiuse imposte

Per lo balcone insinuava il sole

Nella mia cieca stanza il primo albore;

Quando in sul tempo che più leve il sonno

E più soave le pupille adombra,

Stettemi allato e riguardommi in viso

Il simulacro di colei che amore

Prima insegnommi, e poi lasciommi in pianto.

[It was in the morning and, through the closed shutters

along the balcony, the sun brought the dawn

into my blind room at the time when sleep is at its lightest

and most gently covers our pupils:

She stood by my side and looked into my face

the shadow/image of she who first taught me about love,

and then she left me while I wept bitterly.]

Il sogno, a long poem, is for the most part composed as a dialogue in which the “I” comes increasingly to realize that his dead beloved has at least as much cause to feel unhappy as he has himself; the ghost expands the narrator’s grief until it is more empathetic. Leopardi’s narrator can see the phantom while my own experiences during sleep paralysis – episodes for which I don’t claim poetic qualities – usually consist exclusively of auditory sensations; visual ones have never been part of them. An old friend of mine told me that it had been different for him: once, for instance, he confessed to having seen Wagner’s head bumping along on the floor – it is surely not irrelevant that the man is a passionate admirer of Wagner (it’s actually curious that the dancing head wasn’t accompanied by some suitable music but perhaps some higher authority found the prospect a little too extravagant).

Anyway, my second story is about the sound of footsteps and hence I cannot but connect it to the first one:

About thirty years ago, in 1984, I spent a lot of time in a large Oslo flat. I was a kind of associate member of a collective formed by other young people, mostly students. On a mild, snowy January morning, I was still in bed well after the others had left for work or studies. I was on a Magister degree course (as it was known at the time) in comparative literature, but that day there were no lectures or seminars and I had no plans to get up any time soon.

While I was lying there, playing at being a hibernating woodchuck, an attack of sleep paralysis started up. I had already had such episodes and knew that they could be stopped if I could quickly throw myself into another position. This time, I didn’t react fast enough and, for a few seconds, I felt trussed up and suspected that something not very nice would come to pass.

And I wasn’t wrong. While I was in the grip of the would-be paralysis, I heard someone starting to walk in the empty flat. The footsteps, which were quite distinct, continued from the hall and into the sitting room. I knew full well where the steps were heading and couldn’t do anything except lie still and wait for the uninvited guest, who was soon level with the kitchen and then moved on into the short passage leading to my bedroom. The door stood open, the visitor entered and stopped behind the headboard of my bed. Some phantom or other was standing just centimetres away but I was paralysed and couldn’t even turn my head to find out who it was.

An eternity of subjective time passed – a stopwatch or any other watch would have measured out a few seconds – until a quite absurd thought came into my head: “It’s Sigurd!” The paralysis ended at once, which allowed me to make sure that there was no one in my room. The rest of the flat was also empty.

Right enough, one of the men in the collective was called Sigurd. He had taken sciences at school, had a teaching post at the Norwegian Business School and was permanently amused by my complete lack of practical skills and my romantic or humanistic opinions. But he was a kindly soul, enjoyed talking with me on the whole and used to praise the meals I cooked, so I couldn’t understand why I should have conjured him up as a ghost in the bright light of day. I tottered off to the kitchen, drank some coffee, had a sneaky smoke and looked through a few newspapers – rituals intended as a kind of exorcism that wasn’t all that effective. Still, something gradually dawned on me, something I should have grasped much sooner.

My mother’s father was also called Sigurd. He was a truly good man, but it so happened that my first experience of sleep paralysis was in his house. I was staying the night a few days after his death in August 1980 and actually sleeping in his bed. This was enough to produce an unsettling feeling of having broken a taboo, and it was heightened by having an attack of the paralysis that would later become so familiar. During it, the mattress vibrated underneath me and I had a very unpleasant dream about a dead young woman who walked. Could it be Sigurd, my incredibly nice, pipe-smoking granddad, who loved to play with his grandchildren and tell them fairy tales and adventure stories – was it really he who had also come to stand at the head of my bed and, possibly, demanded something from me?

Well, it wasn’t unthinkable but, in retrospect, I have considered a factor that might be especially significant. When “Sigurd” entered my bedroom, I was lying, as we know, on my back in the classical position of the patient on the psychoanalyst’s couch. Instead of standing, the being behind me might have been sitting on an armchair, in the analyst’s traditional place. If so, “Sigurd” would be a case of a Freudian slip: for all I know, my visitor might have been none other than Sigmund.

That would indeed be an unheimlich pointer to his great and lasting influence.