Russian society in the light of the Maidan

Poet and essayist Olga Sedakova takes her fellow Russian writers and intellectuals to task for responding with silence to the light emanating from the Maidan: a light of hope, of solidarity and of rehabilitated humanity. A light that Russia would do well to see itself in.

In light of the Maidan, Russian society is a shameful sight to behold. It is a harsh thing to say, but I cannot think of a milder way to put it. This is of course my own opinion, and there are very few people in Russia who will agree with me. Even the words I have chosen as the title of this piece – “the light of the Maidan” – will be regarded as a direct insult by most Russians. And among them are many usually thought of as “intellectuals” and “liberals”. They would probably be happier if I had used phrases like “The bonfires on the Maidan”, “The acrid smell of smoke on the Maidan” or at best “The drama of the Maidan”. What I know about the Maidan I have learned from very dear friends of mine who have spent the last few months camping out on the square, from direct broadcasts from where it has all been happening, from the way in which the composer Valentyn Sylvestrov has responded to events (I place more faith in the way great artists perceive reality than in anything else). All of this leads me to talk about the light of the Maidan. Of course I mean specifically the peaceful Maidan, unyielding in its peacefulness, not the antics of a few fringe elements, which is all the media have been concentrating on.

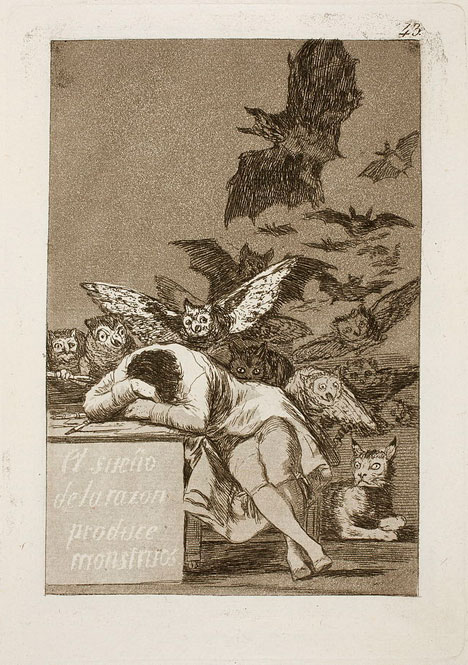

Francisco Goya’s Caprichos no. 43, “El sueño de la razon produce monstruos”, 1797-1799, Museo del Prado. Source: Wikipedia

Above all this is the light emanating from people who have overcome their fear. The victory of the Maidan is a victory over fear, as the philosopher and publisher Konstantin Sigov has called it. While I was reading the never-ending stream of comments from my enlightened compatriots on the events in Ukraine (and I am going to try to address some of them in what follows), I kept calling to mind the words of T.S. Eliot in “East Coker”, one of his Four Quartets:

Do not let me hear

Of the wisdom of old men, but rather of their folly,

Their fear of fear and frenzy, their fear of possession,

Of belonging to another, or to others, or to God.

I’m not saying that our commentators are old men, but rather the only wisdom that they possess is the wisdom bred of fear. The victory over fear – what the Maidan is – is seen through the eyes of people who have not yet emancipated themselves of their fear. They do not see what there actually is; they only see what might come afterwards (and for them, of course, nothing good will come afterwards).

Georges Nivat, French historian of ideas and translator of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, has written about the Maidan as a possible breath of fresh air in a Europe living on compromises and without ideals after the two traumas of the twentieth century – Nazism and communism. He writes that this breath of fresh air is a mere possibility. He is not expecting it to inspire any new resistance to evil. Europe’s reliance on compromise comes from a preference for inner comfort and peace. The fear of being enthusiastic about anything is too firmly fixed in the European mind. In Russia this fear is even firmer.

The light of the Maidan is also the light of hope. Hoping for something that differs from what we already have seems like madness. There are precedents for thinking like this: after the February Revolution of 1917 came October and the Communists (this is the most frequently cited example). Putting it another way: the idealistic stage of the revolution was followed by dictatorship and terror. Then we had civil war and the complete collapse of the country. There is probably no place in the world that is more afraid of revolution than Russia. We have every reason to regard anything at all as better than war and revolution. Such has been the experience of several generations.

Hope for a better life usually lives in spite of past experience – no matter how difficult it has been. In Russia, however, there is no place for such a hope. We feel like we are in some kind of train; it has been set off in a particular direction and it’s rushing along, but no one has asked us where we want to go, and it’s absolutely clear that we aren’t in control of anything. The Russian people lived through the events of the snowy spring of 2011 and now they feel crushed like never before.

The light of the Maidan is also the light of solidarity. There have been many truly outstanding examples of solidarity on the Maidan. This was solidarity without class or national differences. Russia has no experience of solidarity comparable to the Maidan, and there were few instances of it in the past.

The light of the Maidan is also the light of rehabilitated humanity. Russian intellectuals live in an atmosphere of global irony, deep scepticism and cynicism. They place no trust in high ideals, revolutionary romanticism and national pathos. A square packed with inspired people singing the national anthem or saying the Lord’s Prayer together fails to match their understanding of what is “modern” and “contemporary”. Many Russian commentators describe events like these in Ukraine as “archaic” . No wonder. What Russians see as “modern” is all too often nothing more than grotesque buffoonery.

There’s another oft recurring motif in what is said by those who do not like the Maidan – that it’s “all very complicated”. They keep reminding us that nothing is simple, there are no such things as absolute good or absolute evil. The two sides are both right and wrong at the same time. The most we can hope is that they live together in peace. Does that mean we have to live in peace with blatant thieves? Well then, the argument comes , “they” – meaning the opposition – are going to do the same once they’ve seized power. This assertion of complexity that defies comprehension is then bolstered by examples of cruelty on both sides. Facts, however, are offered mainly to confirm the cruelty of “them” – the opposition. Indeed, moral agnosticism is another part of our difficult historical heritage. Should we really be surprised that there is still a refusal to state unequivocally whether Stalinism was “good” or “bad”?

I am here limiting myself to a brief overview of how Russian intellectuals have reacted to the Maidan. I do not wish to talk about those who blather about “eurofascism”, “Banderites” and so on, even if I am very much afraid that they are in the overwhelming majority. Sadly, they are just victims of the “information war” waged by the official propaganda machine. If you listen to the same thing day after day there are bound to be certain consequences.

If I now mention just one of these propaganda motifs, it is simply because it is more complex than the common clichés of “fascism” and “antisemitism”: let me say some words about the Maidan’s supposed “russophobia”.

The people on the Maidan are protesting against the rule of kleptocrats and neo-Stalinists who are not accountable to the people. By this I mean a state in which the power of those in charge is unlimited, they do not have to answer to the people they rule, or inform them of their actions, and all their subjects have to do is offer their rulers their unstinting devotion. Maidan, which opposed this regime, is viewed as anti-Russian – and there are good reasons for this. The regime in Ukraine was supported by Moscow, and Russia itself represents this form of rule in an even more concentrated form. The people on the Maidan are striving to finally leave the Soviet past behind. As recent events demonstrate, such attempts are still punished by Russia where a clear distinction between “Russian” and “Soviet” has yet to be made.

*

In connection with this article, Olga Sedakova published an open letter addressed to “my Ukrainian friends”:

Olga Sedakova: Letter to my Ukrainian friends

All of us in Russia – those of us who are horrified by the prospect of war in Crimea – feel quite helpless at the moment. None of us has the slightest possibility of exerting any influence on decisions taken by our authorities. They broke off any kind of dialogue with their opponents long ago. Appealing to them is useless. The only point of writing appeals is to clear the conscience of those who write them: “I don’t want to be guilty”. Even so, that is not the worst thing. The worst thing is that it is completely impossible to hold a dialogue with the vast majority of our compatriots, who quite sincerely, believing every word, repeat the same loathsome slander that official propaganda feeds them with. This propaganda gives rise to an unprecedented level of aggressiveness. Monsters are born when reason goes to sleep. I beg you not to give up the hope that, even if you cannot forgive the people who have been subjected to these psychological assaults, reason and spiritual health will one day be restored to Russia. Only then will the peace for which we pray to the Lord be possible. No, I do not want to be guilty. I wish you a future that is open and free, a future that evil spirits are now attempting to smother. May God prevent them from succeeding in their intent.

With love and my deepest admiration for your bravery…

Published 15 March 2014

Original in Russian

Translated by

Jim Dingley

First published by Dukh i Litera 4 March 2014 (Russian version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Transit © Olga Sedakova / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

An emotive rift exists between being drafted and signing up for military service. Those who prioritize family responsibilities, education and skills, and non-violence aren’t backing the opposition. Defence comes in many forms. Could lessons from Ukraine’s mobilization inform the recruitment challenges potentially facing the rest of Europe?

Artist Marharyta Polovinko’s creativity persisted in a tormented form through her experiences as a soldier on the Ukrainian frontline. The words of a recently called-up fellow creative and young family man provide a stark reminder that the Ukrainian military is buying Europeans time.