The distinct character of a port city is shaped and re-shaped by flows of people, goods and ideas. Ports are constantly extended, rebuilt, relocated and demolished; new types of vessels and cargoes require changes in the city’s infrastructure, including the docks, railways, bridges, motorways and canals. The needs of the port determine the formation of the entire city.

Gothenburg is no exception. Founded in 1621, its port was first located outside the city. In the late 1800s the port begun to move into the heart of the city and continued to expand up until the 1950s. With the introduction of the container in global shipping in the 1960s and the space demands the new cargo form entailed, it became necessary to move the port back outside the city. This ongoing process of relocation has not only left its mark on the city’s skyline but also, as we shall see, has had the effect of displacing histories.

Temporary conditions

Seamen, dockworkers, migrants, merchants and passengers have all come to Gothenburg throughout its history, some to stay, others to move on: poor and rich, skilled and unskilled, from far away but mostly from nearby. Many people came to the city temporarily, passing through on their way to another destination, or staying for a short time for seasonal work by the water.

For centuries you could always get a job for the day near the waterfront – running errands for a shipmaster or loading and unloading a ship. Some claimed to have chosen a water-related occupation just because it was there: “You could always go to sea”.

When industrialization got underway properly in Gothenburg in the 1850s, hostels or shelters around the city provided temporary lodgings for seamen waiting for work. When strike breakers were borrowed from other cities or countries, they often arrived by boat, which they lived on during their short time in the city.

The flow of arrivals or departures was, then, for a long time one of Gothenburg’s distinct characteristics. The maritime sector, with its merchant fleet, passenger vessels and coastal liners, was central to this. Some flows, however, have shaped the city in more exceptional ways than others.

Migrants create the city

Gothenburg was founded in 1621 for strategic reasons. Sweden wanted to build a city on the west coast to be used as a defence and, above all, as a trading centre with western Europe. Gothenburg originally lay at a sheltered location further up the river Göta, however the deep layers of clay and shallow water areas filled with reeds made the construction of a port difficult. Large sailing ships were obliged to dock outside the city, where cargoes were loaded onto barges for transport to Gothenburg or towns along the river.

Sweden turned to the expertise of the Dutch for the development of Gothenburg’s city plan. The King considered it to be of utmost importance that the city be inhabited by Dutch people to safeguard trade. Some historians would even describe Gothenburg as a Dutch colony at the time. In return, they were offered high-ranking positions, religious and linguistic freedom, tax relief and other privileges.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Gothenburg continued to welcome foreigners, above all craftsmen and merchants. Many came to the city from England and Scotland.

They were often extensively involved in trade; bought land, worked in forestry, campaigned for better waterways, owned warehouses in the city, and had their own quays and ships. Some of these merchants made fortunes from trading in Chinese porcelain and silk and Indian spices, as well as herring from the west coast of Sweden and iron and timber from the woodlands further north.

People on the move

A more central port structure was not developed in Gothenburg until the late nineteenth century, by which time many European ports had already begun to move out of the cities. Rapid industrialization and urbanization was now underway; canals were extended and railways built, with steam power making it possible to control arrival and departure times. All this increased the flow of goods and people, especially from the hinterland nearby.

Rural poverty caused by crop failures, together with rapid population growth, cultural and political suppression and facilitated means of travel created a massive urbanization process. In the 1850s, a vast number of the Swedish population also attempted to emigrate. Over a period of 80 years, beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, 25 per cent of the Swedish population, or 1.3 million people, migrated to other parts of the world, mostly North America.

Gothenburg became the focal point for people dreaming of a better life. This was where the ships were waiting to take emigrants to England, from where they would continue their journey on one of the big British steamers across the Atlantic. During the last wave of migration a direct Swedish-American line was established (the Svenska Amerika Linien in 1915). These flows of people shaped the city; the areas near the dock were filled with emigration agencies, hotels, stores, pubs and brothels open all hours. The emigrants were mainly young people, the largest group among them single women. Many had worked to buy a ticket. Far from everyone hoping to emigrate succeeded: women that remained in Gothenburg often worked as domestic servants, while men took work in industries or at the docks.

Industrialization

The increasing population and volume of goods tested the city’s infrastructure to its limits and the central port structure was developed extensively throughout the early twentieth century. Completed only after years of discussion, the new port development was crowned by a new, large and very modern port in 1922 in the very heart of the city. Despite doubts over the wisdom of building at the shores of the narrow river, given the fact that ships were growing bigger and bigger, the symbolic value of a visible port seems to have carried more weight.

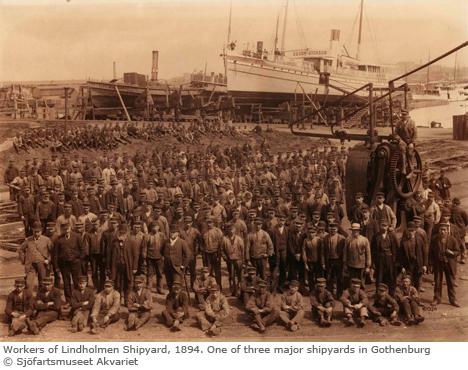

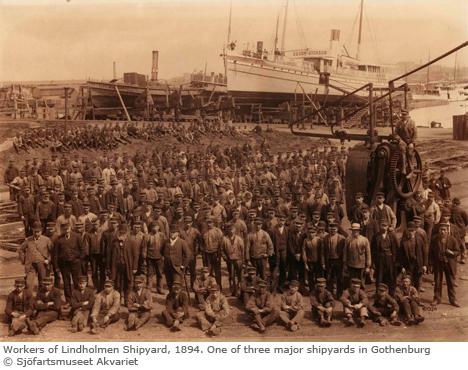

Together with three big shipyards, set up in the late nineteenth century, the new port came to be the strongest visual manifestation of Gothenburg for years to come. Images from the 1940s and 1950s showing the port as a visible, open structure with hundreds of cranes, ships being launched from the shipyards and quays serving as meeting places and esplanades are widely used in representations of Gothenburg as a port city.

Nevertheless, working conditions remained insecure well into the twentieth century, with poverty and overcrowded housing. Seamen, shipyard and dockworkers lived close together in areas by the water, crossing the river to the docks on one of the many ferries going back and forth. The workers were a dominant part of the city’s appearance. Gothenburg had a strong industrial feel, visible to all entering the city.

Gothenburg’s shipyards avoided destruction during WWII, giving them an advantage over their international competitors, and by the mid-twentieth century the city’s shipyards had became world leaders.

The growth of the shipyards and other industries in the city required more manpower than was available. Women were employed in traditional male occupations and immigrant labourers became crucial. In order to entice workers, agreements were made in the 1940s with Hungary and Italy, among others, to allow workers to come to Sweden. In 1952, the Nordic Passport Union made it possible for citizens of the Nordic countries to travel, live and work in the region without a passport or a residence permit. Finns in particular came to Gothenburg to work in the shipping industries. In the 1970s, the shipyards launched recruitment drives within Sweden and abroad, drawing workers from all over Europe, especially from Yugoslavia.

At its peak in the late 1960s, Gothenburg’s shipbuilding industry employed 15,000 people and ensured work for many other businesses that supplied the shipyards with goods and services. The shipyards played a formative role in creating the image of the city, generating income and developing a strong sense of community amongst the many workers.

City disconnected

The Swedish shipbuilding industry was hit by a major crisis in the 1970s and after 1980 almost nothing was left. Gothenburg’s former image as a great industrial city soon became a symbol of something lost. There are many explanations to why the Gothenburg shipyards were closed: the shipping crisis brought on by a combination of rising oil prices and competition from Japanese shipyards were hard blows. Some blamed incompetent management, others the demands of the unions.

The container had been introduced by America during the peak of the shipbuilding industry in the 1960s. Moving container cargo required a port with flat and asphalted areas, connected docks and more powerful cranes. A new port had to be built outside Gothenburg, where there was enough land. The first container port opened in 1966; little by little, the whole structure of Gothenburg’s inner city port moved out of the city. Today, almost all operations are concentrated in the outer docks.

Together with the closure of the shipyards, this caused rapid and extensive changes in the urban landscape. Industrial wastelands opened up, cranes were removed and the city fell silent. Industries dependent on shipbuilding faced recession and tens of thousands of employees lost their jobs. Inner-city, working-class areas close to the water were demolished – ironically, the rubble was used as filling material for the the new outport – and former residents moved to newly built suburbs. Living standards there were higher but communities that had developed over the course of a century were shattered.

In the 1980s, politicians and private industry began drawing up plans to transform the post-industrial city into a “knowledge” or “event” city. The old port and shipyards were marketed as the site of the future city. Companies, as well as Gothenburg University, were encouraged to establish activities in the old industrial buildings; expensive residential areas were constructed. Substantial investment in tourism was also made.

This reconversion of the former port was in line with developments in harbour cities worldwide.

Invisible port, invisible world

Today, goods travel to and from Gothenburg in ever greater quantities. The city’s out-port is the largest in Scandinavia, serving direct lines to the US, India, Central America, Asia and Australia. The activities generated by the port remain central to the city’s growth. Yet the number of people in Gothenburg earning an income from maritime occupations is declining. Ship owners still reside in the city, but in many cases their ships sail under flag of convenience.

Swedish seafarers are rare if they are not captains. This is one result of the global division of labour and economy, where most seafarers come from low-income countries. In Gothenburg, the maritime focus is rather on research on ship design, logistics and shipping finance. Migration to the city is extensive, but people do not arrive by boat, and of course no longer work in any maritime industry.

The port – both the goods and the people passing through or working in it – used to be visible, open and loud. Today, the work has radically changed: the physical port structure is very much off limits. At the same time, local politicians and private businesses have turned to the old, inner-city dock areas in search of a tangible identity, employing what could be described as a distorted understanding of history. The regeneration of the old dock has been promoted as furthering the city’s “harbour identity”. But the identity is presented as clean, silent, and with a view. This romantic view of the old port fails to acknowledge the workers, the conflicts, the dirt and the poverty that used to come with it. A recycled maritime heritage attracts a flow of people and capital to Gothenburg, marketed as a “harbour city”.

This type of development is common to port cities all over Europe. As the artist Allan Sekula writes in his work Fish Story, “Shipyards are converted into movie sets. Harbours are now less havens […] than accelerated turning-basins for supertankers and container ships. The old harbour front, its links to a common culture shattered by unemployment, is now reclaimed for a bourgeois reverie on the mercantilist past […] the backwater, becomes the frontwater. Everyone wants a glimpse of the sea.”

In Gothenburg, few inhabitants at first wanted to move to the old industrial sites. Concerts with the Rolling Stones and Madonna in 1990 were one strategy employed to attract people to the area. Back then, the fact that the sites were situated by the water mattered little to local citizens, with their own experiences of the industries. Today, a view of the water is of utmost importance when putting new apartments on the market.

Why are only certain features of the maritime heritage spoken of and used, and what is suppressed? Who is benefitting from this and whose voice cannot be heard?

Nostalgia is perhaps the main feature in the creation and legitimization of the harbour city narrative. Historical aspects are used only when they improve the image of an attractive city fit for a particular lifestyle. Yet the debate around the regeneration of the old dock areas overshadows more contemporary challenges: segregation, increasing income gaps and gentrification processes.

The use of history and cultural heritage for promoting and rebranding places should always be questioned carefully. Often, it is a superficial attempt to claim quality and to play on emotions and feelings. But history should be regarded as an incomplete process; an ongoing conflict between various alternatives, all of which are need to be depicted.