Brexit is the price Britain is paying for the failure to hold an honest discussion about immigration, multiculturalism and Empire. But it would be a mistake to think that the UK’s problems are without equivalent elsewhere, writes Gary Younge.

The notion that India has much to offer Europe spiritually but little politically has been prevalent for centuries. However, a history of multiculturalism is incomplete that does not include the Mughal emperor Akbar’s enlightened and inclusive view of society and religion, revived in the Indian constitution of 1950.

In January 1556, the Emperor Humayun tripped over his cloak and tumbled to death down a flight of stairs in Delhi, bequeathing a fragile kingdom to his thirteen-year-old son, Jalaluddin Muhammad Akbar. Against the odds, the Mughal dynasty, founded by Humayun’s father Babur, flourished. Akbar gradually took charge of political affairs, shrugging off the influence of his former regent Bairam Khan and former wet nurse Maham Anga. He conquered Malwa, Rajputana, Gujarat, Bihar and Bengal in the years between 1560 and 1575 and built himself a new capital called Fatehpur Sikri.

In 1585, he moved to Lahore to tackle disturbances along the empire’s western fringe, and stayed to annex Kashmir, Sind and Baluchistan. On his return thirteen years later, he chose the erstwhile capital Agra over the city he had commissioned, which lay a mere 35 kilometres away. Fatehpur Sikri was completely abandoned soon after the emperor’s death in 1605 and became a ghost town, resurrected in the twentieth century as a picturesque tourist attraction.

Buland Darwaza gate to Jami Masjid mosque, Fatehpur Sikri. Photo by Marcin Białek from Wikimedia Commons

The period between 1575 and 1585 was a calm spell in the middle of a reign of five decades otherwise marked by constant battles. Akbar focussed in these years on acquiring a deeper understanding of philosophy, religion and the arts. He surrounded himself with learned courtiers, and in 1575 constructed an Ibadat Khana or house of worship, as a venue for discussion on matters of faith. Every Thursday evening, he would preside over extensive theological debates, during which Sunnis, Shias and Sufis contended to bring the monarch round to their viewpoint.

Disillusioned by inter-denominational bickering that produced more heat than light, Akbar broadened his search by summoning Jains, Hindus, Zoroastrians and Christians to contribute to the discourse. In 1578, he sent letters of invitation to the Portuguese rulers of Goa on India’s west coast. The Europeans suspected a trap, since they were in conflict with the Mughals over control of the Indian Ocean, but the prospect of bringing into the fold of Christendom one of the world’s most powerful rulers was tantalizing. They dispatched to the Mughal court three volunteers, the Italian Rudolf Acquaviva, the Spaniard Antonio Monserrate and the Iranian convert Francis Henriquez, who served as translator.

Acquaviva, a young man from a noble family, was eager for martyrdom. He excoriated Islamic beliefs and the character of the Prophet Muhammad at the Thursday debates, hoping to scandalize those present into condemning him to death. Instead, the Emperor, who had received with reverence ornate copies of the Bible the foreigners had presented on arrival, permitted the attacks and encouraged the missionaries to preach freely in their spare time.

The women of the zenana, fearing they would be thrown out if the ruler converted to a firmly monogamist creed, were horrified by the presence of the Jesuits. Their anxiety peaked when Akbar placed his second son Murad Mirza in the Christians’ care. The Emperor, however, had no intention of rejecting the religion of his birth in favour of Jesus worship. He was in search of ideas that tied faiths together, transcending the divisions apparent in the Ibadat Khana, where erudite scholars frequently descended to name-calling and petty insults. In the words of the orthodox Muslim courtier Abdul Qadir Badauni, who wrote a chronicle of Akbar’s reign:

The Emperor … by a peculiar acquisitiveness and a talent for selection, by no means common, had made his own all that can be seen and read in books … and from the general impression this conviction took form … that there are wise men to be found and ready at hand in all religions … and that the Truth is an inhabitant of every place.

Badauni composed his account in secret, as a counter to the official biography of the Emperor written by the freethinking courtier Abul Fazl, and as a warning to future generations of Muslims against what he called, ‘a complete revolution, both in legislation and in manners, greater than any recorded for the past thousand years’. His dim view of Akbar’s radical syncretism was shared by the European guests, who considered Islam an enemy religion and dismissed Hindu belief as base superstition. Within their Indian dominions, they permitted no religious practices aside from Roman Catholic rites, and had instituted the Inquisition in the 1560s to weed out backsliding by converts suspected of worshipping their former gods in secret. Three years after setting out for Fatehpur Sikri, the fathers returned to Goa with little to show for their pains.

Miniature of Emperor Akbar. Image via Los Angeles County Museum of Art from Wikimedia Commons

One consequence of the Fahtehpur Sikri discourses was the development of a faith called the Din-E-Ilahi (the religion of God). It is unlikely that Akbar viewed it as a new universal doctrine, since he made no attempt to proselytize beyond a narrow circle of the nobility. He adapted aspects of each major religion – Hindu sun worship, Parsi fire worship and the Jain respect for animal life – but this assortment did not add up to a coherent belief system. As a route to evolving a super-religion, the deliberations in the Ibadat Khana and his private conversations with sages were deeply unproductive. In statecraft, on the other hand, he put in place profoundly consequential reforms based on his evolving idea of the dignity of all faiths.

In 1579, he pressured leading Muslim clerics and scholars, collectively known as the ulema, to endorse a document that made him the highest interpreter of religious law. Once the ulema had signed the declaration, their role was reduced to scouring Islamic jurisprudence for justifications of royal proclamations. The few religious leaders who refused to submit and instead fomented rebellion were put to death.

The year after he cut the orthodoxy to size, Akbar abolished the jizya, a tax mandated by the Quran and applicable to dhimmis, or protected people. The term originally covered Jews, Christians and Sabeans, but was extended to members of other faiths as Islam spread beyond Arabia. The jizya provided substantial revenues to the Ottoman Empire and was imposed in Moorish Andalusia throughout the period of semi-mythic inter-religious harmony known as La Convivencia. There were scattered instances of kings having eliminated the tax on dhimmis, and Akbar himself had briefly abolished it early in his reign, but the proclamation of 1580 resulted in the most far-reaching and durable abrogation of the discriminatory and burdensome tax in the millennium since the start of the Islamic calendar.

The removal of the jizya was part of a wider political push for parity between religions encapsulated by the phrase sulh-i-kul, or ‘universal peace’. Sufi mystics used that term in a religious context, but Akbar was the first to give it a political turn. His predecessors Humayun and Babur, though nominally Sunni, had welcomed Shia officers at a time when the rising Safavi dynasty was converting Iran and the surrounding regions to the Twelver Shia faith, precipitating a conflict within sixteenth century Islam as fierce as the one the Protestant Reformation had set off at the same time in Europe. Akbar extended the liberalism of his forefathers to all faiths, transforming the Mughal administration into an ecumenical meritocracy.

Freedom of worship was not invented in Mughal times, having been authorised in different eras by Indian, Roman, Chinese and Mongol rulers, among others. What set Akbar apart was his placement of religious equality at the heart of political philosophy, and his conviction that such equality could not be achieved through disinterested tolerance or non-discrimination. Rather than separating governance from religious matters, he promulgated laws and took administrative measures that engaged actively with disparate creeds in order to make citizens feel welcome and cared for.

He gave grants for the building and maintenance of temples, stimulating the extraordinary growth of the cult of Krishna centred in Mathura and Vrindavan, two towns close to Agra and Fathepur Sikri. He prohibited cow slaughter because it offended caste Hindus. The injunction was not enforced uniformly across the domain but scrupulously followed in regions such as the Punjab, where emotions against cow slaughter ran high. In Gujarat, butchery was forbidden during Jain festivals to satisfy a community that placed the highest value on the sanctity of sentient life.

His respect for religion did not, however, extend to condoning every practice associated with faith, no matter how unjust. Sulh-i-kul (harmony and peace to all) was balanced by two other duties of kingship, the rah-i-aql, or path of reason, and rawa-i-rozi, or provision of livelihood. He forbade sati, the immolation of widows, when it involved compulsion. After a Hindu Rajput general named Jai Mal died during a campaign in 1583, the Emperor heard through the women’s quarters that Jai Mal’s widow was reluctant to die by fire but was being forced by her son Udai Singh. He rode out personally to save the woman, afraid that sending junior officials would only cause confusion.

He liberated his slaves, banned the slave trade, prohibited child marriage and encouraged the remarriage of widows, a taboo in certain Hindu communities. He disagreed with Muslim inheritance laws that gave women only half the share due to men, though this provision was at the time superior to what Christian and Hindu women could expect.

His attempts at social reform were not as thorough or impactful as the effort to create a harmonious multi-ethnic and multi-religious society, but the propagation of sulh-i-kul was an astonishing achievement in itself, engendering a legacy that has lasted centuries.

Akbar’s tomb, Agra. Photo by Rajesh Kapoor from Wikimedia Commons

As the seventeenth century progressed, ever more Europeans visited India, and many wrote accounts of their travels. Akbar’s name became well-known in educated circles in the West, but the Mughal empire came to be viewed more as a classic oriental despotism than the site of an original experiment in statecraft. In the eras that followed, Hindu and Buddhist mystical ideas, transmitted to the West through translations commissioned in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, made a substantial impression on western thought. The notion that India had much to offer Europe spiritually, but could contribute little by way of political ideas, took hold and continues to persist.

Akbar’s drive for inter-faith amity enjoyed a revival towards the end of the nineteenth century, by which time important chronicles produced in the emperor’s lifetime had been translated into European languages. Akbar, een Oostersche Roman (‘Akbar, an Eastern Romance’) by Petrus Abraham Samuel van Limburg Brouwer was published in Dutch, at The Hague, in 1872. Prince Frederick of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, an Orientalist who travelled to India three times, wrote a laudatory biography in German titled Kaiser Akbar. Ein Versuch über die Geschichte Indiens im sechszehnten Jahrhundert (‘Emperor Akbar: A Contribution Towards the History of India in the sixteenth Century’) published in Leyden in 1880. Colonel George Bruce Malleson’s Akbar and the Rise of the Mughal Empire, which came out in 1896, portrayed, ‘the promulgator of a system which we English have to a great extent inherited, as a conciliator of differences which had lasted through five hundred years’. Unlike Prince Frederick and van Limburg Brower, who believed Europe could gain from comprehending Akbar’s ideas, Malleson suggested that the emperor’s beneficial principles had already been absorbed by the British colonial administration.

A deeply interesting text that took account of both positions was Alfred Lord Tennyson’s long poem Akbar’s Dream, composed in 1892, the year of the poet’s death. It was published with annotations explaining the historical background of certain references in the verses. At the poem’s opening, we encounter the Emperor meeting Abul Fazl at night in front of his palace at Fatehpur Sikri. On being asked why he looks sombre, Akbar prefaces his answer with a summary of his philosophy:

I let men worship as they will, I reap

no revenue from the field of unbelief.

I cull from every faith and race the best

and bravest soul for counsellor and friend.

I loathe the very name of infidel.

I stagger at the Koran and the sword.

I shudder at the Christian and the stake.

Tennyson appears to be presenting Akbar’s combination of profound spirituality and abhorrence of sectarianism as a model for a Europe riven by doubt and dissension. Near the end of the poem, however, a peculiar transformation occurs. The Emperor narrates his dream, beginning optimistically by describing a shrine he built, which belonged to no single faith and where, ‘Love and Justice came and dwelt’. In the dream, he watches with horror as his companion Abul Fazl is killed at the command of his estranged son Salim and sees his own demise soon after. Akbar’s heirs betray his ideals, the sacred temple is shattered, and from its ruins arise, ‘The shriek and curse of trampled millions’. In the end, harmony is restored by the British, who rebuild Akbar’s inclusive shrine:

From out the sunset poured an alien race,

Who fitted stone to stone again, and Truth,

Peace, Love and Justice came and dwelt therein.

The year after Tennyson’s poem appeared in print, its rosy view of British colonialism was contested by Rabindranath Tagore who, twenty years later, would become Asia’s first Nobel Laureate. In his essay Englishmen and Indians (Ingrej o Bharatbashi), Tagore wrote that the British:

Have sown the seeds of jealousy rather than love between the two major communities of India … Because the English policy lacks that ideal of love by which Akbar tried to unite fragmented India, the habitual dispute between the two peoples, instead of decreasing, is showing every sign of further aggravation. Only laws and disciplinary measures cannot unite people; you need to enter into their hearts, understand their sufferings and have to love them sincerely… Trying to restore peace solely by employing police force and handcuffs might vouch for overwhelming authority but that was not what Akbar’s dream was about.

Officials of the British Empire usually viewed Hinduism and Islam with contempt. They employed the formal distance of the state from religion to intensify feuds rather than soothe them. Where Akbar, in Tennyson’s words, sought to, ‘alchemize old hates into the gold of Love’, the British alchemized them into the gold of power.

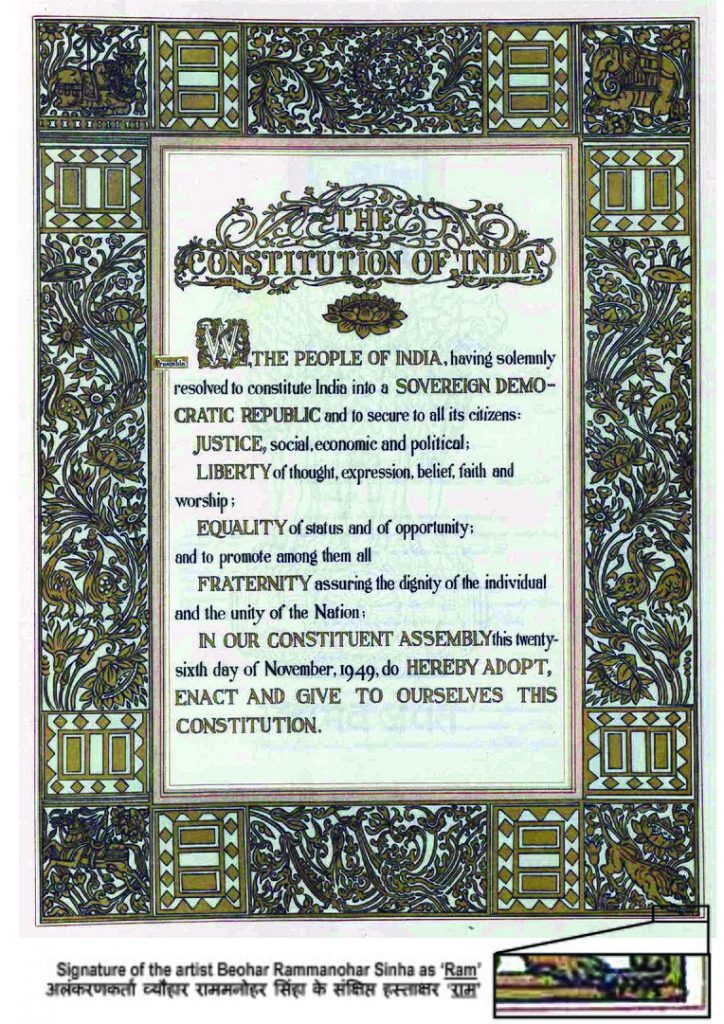

The independent Indian republic that came into existence in January 1950 was a crystallization of Akbar’s progressive ideals in democratic form. The constitution’s three primary aims, the fostering of harmonious relations between communities, the cultivation of a scientific temper and the provision of social justice, corresponded with the principles of sulh-i-kul, rah-i-aql and rawa-i-rozi. The Indian state’s Akbarite orientation is underestimated and misunderstood by contemporary analysts, even those like the Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen who highlight the Mughal king’s historical importance.

Constitution of India. Photo from Wikimedia Commons

In his book The Argumentative Indian, Sen critiques the tendency to interpret cultures, ‘in ways that reinforce the political conviction that western civilization is somehow the main, perhaps the only, source of rationalistic and liberal ideas. This sets up cultural assessments based on distance, where the aspect of culture farthest from the West is seen as most authentic.’ Arguing against the notion of India being primarily a spiritual civilization, he enumerates its accomplishments in fields dominated by reason, from mathematics to linguistics to politics. ‘In Akbar’s pronouncements of four hundred years ago on the need for religious neutrality on the part of the state,’ he writes, ‘we can identify the foundations of a non-denominational, secular state which was yet to be born in India or for that matter anywhere else.’

Yet sulh-i-kul was never a philosophy of religious neutrality or disinterested tolerance. Nor, as it happens, was the political philosophy of Gandhi, another historical figure who features prominently in The Argumentative Indian. Gandhi’s rhetoric was saturated with religious symbolism, a fact that made the progressive Left deeply uneasy. Like Akbar, though employing non-violence rather than authoritarianism, Gandhi sought to inculcate inter-religious harmony through positive engagement. Unlike Akbar, he placed himself within a particular faith, in this case Hinduism, and reached out to Muslims and Christians as a Hindu.

Both Akbar and Gandhi tapped into a long tradition of Indic poetic and philosophical thought and merged this with ideas originating elsewhere in Asia and Europe to frame a relationship of the state to faith better described as multiculturalist than liberal or secular. In keeping with that impulse, India’s constitution and penal code make special allowances for religious customs, and the Indian state provides a wide latitude for public expressions of belief. A few examples will provide a flavour of what this means in daily life, though it is by no means an exhaustive list. Pandals, or temporary pavilions, colonize pavements and roads across India as part of Hindu festivals such as Ganeshotsav and Durga Puja, without much care for the convenience of pedestrians and drivers. During Friday afternoon congregational prayers, Muslims spill out of mosques, blocking streets for the duration of the namaaz (worship).

While criminal laws are common to all citizens, communities are entitled to their own civil laws. Muslims are governed by sharia codes, which permit polygamy and distribute inheritances unequally between male and female heirs. Sikhs are exempted by the Motor Vehicles Act from donning helmets while driving scooters and motorcycles, because the wearing of turbans is considered essential to their faith. A number of Jain and Hindu temple towns forbid the slaughter of animals and the sale or consumption of meat and eggs within municipal limits. Bhang, an extract of cannabis usually imbibed with milk, is freely available near many temples, being associated with the ascetic Lord Shiva, while the sale or consumption of other cannabis products is prohibited. A law against ‘creating enmity between religions’ is meant to curb hate speech, but is often utilized to silence political critique.

These provisions were put in place to assure members of religious groups that the state cared for their beliefs, but that inclination occasionally contradicted the new nation’s equally strong progressive and rational impulse. An example of this was the case of cow slaughter, a cause of conflict for centuries in India.

Responding to Hindu demands for protecting cows, the makers of the Constitution covered up the religious nature of the issue in technical garb, placing a clause in the non-binding Directive Principles of State Policy which reads, ‘The State shall endeavour to organize agriculture and animal husbandry on modern and scientific lines and shall, in particular, take steps for preserving and improving the breeds, and prohibiting the slaughter of cows and calves and other milch and draught cattle.’ The last part of the sentence is a complete non-sequitur, for among nations that successfully organize animal husbandry on scientific lines, none consider it necessary to prohibit cow slaughter. The ambiguity in the legislation has created a slow-burn tension and been the basis for Muslims being lynched in the present day by right-wing Hindus, ostensibly for transporting cattle to be butchered.

Secularism has taken very different forms in other parts of the world. In France, the leading nation in Europe’s march to a secular society, the anti-clericalism of the Revolution informs contemporary laws, which are neutral between faiths but can appear hostile to religious expression. Since native Christians have adapted to the framework of the French republic, it is newer minorities who feel targeted by such regulations, which are couched in the discourse of rights. The 2011 ban on the face veil, based on the contention that it was an affront to women’s equality and liberty, is a case in point.

It is worth recalling, in this context, that the first European law banning the slaughter of animals without prior stunning was passed in Germany in 1933. Adolf Hitler and many of his Nazi colleagues were committed to animal rights, and also prohibited vivisection and restricted hunting, but it is no coincidence that mandatory stunning rendered kosher slaughter illegal. This extreme example demonstrates that seemingly progressive measures can spring from complex motives, and that legislation claiming to further equality can be rooted in ethnic and religious bias.

The integrationist laïcité of the French state is at one end of a spectrum of responses to the increasingly multi-ethnic and multi-religious nature of European societies. Demographic compulsions guarantee that citizens who are one or two generations removed from Asia and Africa will make up an ever-larger portion of the population of western Europe. Those who believe the increasing diversity of Europe is a strength that ought to be nurtured can be placed in the multiculturalist as opposed to assimilationist camp.

Just as there is an extreme form of assimilationism, there is an extreme form of multiculturalism. It is a type of moral relativism that the philosopher Bernard Williams labelled ‘the anthropologist’s heresy’. In this view, cultures are homogenous and hermetic, while in reality they are porous constructs with their own hierarchies. Vulgar relativists propose that all cultures have their own values, which are internally valid, and no group ought to impose its values on another. However, the argument that ‘no group ought to impose its values’ is dependent upon the very universality it rejects when it insists morality is a matter internal to cultures. If values only exist within specific cultures, one can make no moral judgement at all about how cultures ought to relate to each other, or how modern states ought to relate to cultures.

Between assimilationism and vulgar relativism lies a realm of multiculturalism that throws up difficult questions about the balance between group rights and individual rights, which parallels the balance between sulh-i-kul, the impulse to harmonize cultures, and rah-i-aql, the path of reason, that occasionally compels the rejection of traditions and customs. Sadly, histories of multiculturalism, which have proliferated in recent years, pay little heed to the example of Akbar or the history of the Indian republic, treating multiculturalism as a recent development within affluent societies.

Attending to the longer history of pluralism will not provide ready solutions. India has made a series of choices difficult to justify from a liberal perspective, frequently privileging the beliefs, emotions and rituals of religious communities over the interests of individuals outside those communities or those oppressed within them. This has doubtless contributed to the nation’s survival as an enduring geographical entity for seven decades, something few people believed possible when it gained independence. On the other hand, the strain caused by asymmetrical legislation has been a boon for conservatives, presenting them with a profusion of wedge issues to exploit, and culminating in the country being ruled, for the first time in its democratic history, by a political party that both adheres to a majoritarian ideology and commands a comfortable majority in parliament.

European rightwing parties with an anti-immigrant platform have enjoyed a surge in popularity paralleling that of India’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party. If the successes and failures of the multiculturalist experiment inaugurated in Fatehpur Sikri in 1575 are any indicator, the new fractures within Europe will not be healed quickly or easily. Not only is there no formula for calibrating how far a state should go in accommodating traditional customs, legislation in itself will never suffice in making immigrant populations feel at home. It is not just a matter of minorities’ relationship with the state, but of their interactions with the majority. If anything keeps liberal Indians hopeful about the future of the nation, it is the daily experience of genuine mutual regard between members of different communities. It is the philosophy of Akbar practised unselfconsciously, as a way of life.

Published 27 May 2020

Original in English

First published by Ord&Bild 1–2/2020 (Swedish version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Ord&Bild © Girish Shahane / Ord&Bild / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Brexit is the price Britain is paying for the failure to hold an honest discussion about immigration, multiculturalism and Empire. But it would be a mistake to think that the UK’s problems are without equivalent elsewhere, writes Gary Younge.

For the US today, tariffs serve the same purpose as bombs. But Trump’s revival of 19th century-style economic imperialism may be alienating his international far-right allies – with one exception: Russia.