The official Remain and Leave campaigns both share two false premises:

1. that we in the UK are not European

2. that Britain is politically stable and economically successful

From this dual vantage point – or rather disadvantage point – it apparently makes sense to talk about how we can “get the best of both worlds” from them, how much they are failing to be democratic, unlike monarchical us, how we in the UK can “lead” them (Gordon Brown).

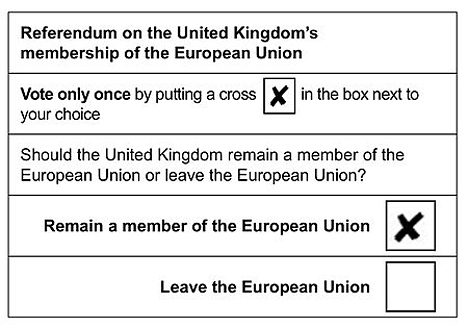

The double-falsehood is no place to start a debate on the future of Britain and Europe. I want to rub this point home. For I am part of the band who does not believe that whether or not we should be in the EU is a matter of calculation, profit or instrumentally computed advantage. The decision to have a plebiscite on whether the UK should Remain or Leave the EU has been called by a prime minister who did not want to have it, does not believe in the process, and will – as I have shown – say anything his spin doctors tell him or his teleprompt puts in front of his eyes. The result of this unprincipled exercise is a debate dominated by arguments over financial gains and losses with both sides greedy for profit at the expense of the EU. Give us our money back, say the outers. Give us “the best of both worlds”, say the inners. What a crapulent, humiliating way of talking about what kind of country Britain is. Nor are Labour’s Remain arguments immune from this approach: when Labour supports remaining in the EU because it has extended workers rights, it too treats the EU as just a means to an end.

There are other universes too: above all, the EU’s own self-regarding one, which is at least as bizarre as Westminster’s. The European Union’s parallel universe is filled with a narcoleptic atmosphere deprived of oxygen – its institutions seem ubiquitous yet tenuous, apparently transparent yet suffocating. Show me the diagrams for the relationship between the Commission, the Parliament, the Council of Ministers, Ecofin, the Eurogroup and Coreper; show me the way to the next whisky bar, oh don’t ask why… Here is the latest introduction to its legal database. Europe does not just issue a torrent of regulations, laws, treaties, judgements and proceedings: there are also scenarios, pamphlets, studies, and theories, realist, neo-functionalist and so on, that are mind-numbing not because they are necessarily badly written but thanks to the airlessness of it all.

An outstanding exception is Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s Brussels, the Gentle Monster (2011). A slim 80 pages by the wonderful German poet and essayist published in 2011, he went to the buildings with a thousand windows to see what went on within. Dry and understated, it is impossible to read without shaking with laughter. On all those words, the poet observes that by 2005 the accumulated laws and regulations of the Union “which no soul has ever read” came to over 85,000 pages weighing “as much as a young rhinoceros”. Five years later and they weighed as much as two young rhinoceros. EUR-lex, the database of all legal orders, records, ran to a grand 1,400,000 documents. This may be unfair as it includes multiple translations. From what I can make out, the EU is generating between 10,000 and 20,000 documents a year since 2010.

Inspired by Enzensberger’s example without hoping to emulate his poetic brevity and touch, I want to try and understand what the European Union is, knowing that it is a changing and growing process. It can’t be reduced to a single, teleological project whose only objective is the creation a super-state. Nor is it just a parliament for our continent. It is not a simple “thing” like a bus or train. So what is it that the British voters must now decide whether to remain in, or to leave? The answer demands a necessarily difficult analysis, not least because British policy has been bound up in the EU’s current development. To try and answer it I’m going to set out some of the stages of my efforts to comprehend the EU on my journey to DiEM25.

The Monnet method, incremental transformation

The European Economic Community or EEC (also known as The Common Market) of the six original countries, France, Germany, Italy, Holland, Belgium and Luxembourg, came into existence with the Treaty of Rome in 1957. It is now the European Union. I will keep to its current name throughout. As with many Brits at that time it was for me a background noise of failed attempts to join it, conducted by humiliatingly incapable governments Conservative and Labour, until Edward Heath became premier in 1970 and negotiated entry in 1972. This was the founding moment of the Brexit debate. Then as now it was fought within and between the Tories, with Enoch Powell combining the figures of Nigel Farage, Michael Gove and Boris Johnson in his singular character. (He aroused a hatred of immigrants that outruns Farage, spoke with the precise intellectualism of Gove, wrote better Latin than Johnson and harboured an ambition that matched them all).

But there were differences. Most important, Heath was wholeheartedly in favour of Europe, making it a clash of principle. Second, there was no referendum. Instead there was a “great debate”, including a six-day one in the Commons (it is very revealing that, as I pointed out in the introduction, the Commons has not debated the deal negotiated by the prime minister at all, merely been allowed to ask him some questions when he presented it to the house).

The 1972 debate exposed a paradox. The supposedly internationalist Left, whether Labour, socialist or Marxist, was almost universally opposed to entry whereas the supposedly nationalist Tory party overwhelmingly embraced it. Tom Nairn wrote an extraordinary, sustained essay, “The Left against Europe” exposing the forces at work. It ran to a complete issue of New Left Review. Since I was then junior member of its editorial committee and there was a rota for editing and putting issues “to bed” in the physical process of the time, I found myself in charge of publishing one of the greatest pieces of English polemical writing of the twentieth century. I put this extract on the cover:

To be in favour of Europe […] does not imply surrender to or alliance with the Left’s enemies. It means exactly the opposite. It signifies recognizing and meeting them as enemies, for what they are, upon the terrain of reality and the future.

The experience has stayed with me. We are in a world that is profoundly right-wing, dedicated ideologically to the false idea that wealth is created and spread for the good of all by competition rather than being appropriated by power. Any effort to resist and replace this has to be where it is hardest and most decisive.

I voted “Yes” to Europe in the referendum of 1975.

My next shaping encounter with the EU came a decade later, when I was asked to help draft and then started to run Charter 88. The Charter 88 appeal for human and democratic rights and a written constitution was a conscious attempt to make Britain a contemporary European country. It went out of its way to say:

part of British sovereignty is shared with Europe; and the extension of social rights in a modern economy is a matter of debate everywhere. We cannot foretell the choices a free people may make.

If Charter 88 had a defining cry it was “Citizens not Subjects!” This remains an all too relevant call in the UK. It means that sovereignty should be vested in the people thanks to a democratic constitution we can call our own, not in “the Crown in Parliament”. But modern citizenship itself in a fast changing world of over-lapping sovereignties is a rich area for discussion and education. So I took an intense interest in the issue. (For an up to date engagement see Benjamin Ramm’s “Citizens’ Manifesto“). Keeping the Charter’s campaign relevant to developments in Europe was also part of my job. So in 1992 I fell upon the EU’s new Maastricht Treaty to read it for myself as soon as it was published, doubtless one of the few people in the UK to do so. I was gobsmacked. Without any advanced warning from the media that I was aware of I read that the twelve male heads of state gathered in Holland had

RESOLVED to establish a citizenship common to nationals of their countries

Indeed, they had inserted a new section into the Treaty “Citizenship of the Union” which stated that

Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union

To which I could only say, “Really?”. Followed by, “This is unbelievable”. Followed by something a great deal less polite.

Citizenship is a powerful concept. How can twelve men “Resolve to establish” it for over 370 million others without even letting them know in advance?

Something shady was taking place. Citizenship needs to be fought for, argued over and above all claimed. Now “every person” of the member states was re-branded without a by-your-leave. There can be moments in relationships when the person you love does something and part of you goes “uh oh” and you try not to think about what it foretells. Only afterwards do you look back and realize that a ruinous flaw was revealed. I was campaigning flat out for citizenship in Britain. Suddenly, without any forewarning, my – no, our – European citizenship had been bestowed upon us like a sentence, through a secret process that I could do nothing but abhor. Here was this wonderful, transforming organization that I admired and respected, even if I did not love it. And it had acted with complete distrust of its own people.

When I stopped running Charter 88 in the mid-nineties I tried to think through the implications in terms of the combination of nationalism, democracy, capitalist globalization and constitutional progress that marked the century’s last decade. Two arguments stood out from the dross with respect to the EU. Alan Milward’s great book, The European Rescue of the nation-state (1992 / 2000) showed me how, country by country, the European Union grew out of the need for a profound post-war reconstruction, including full employment, welfare and education, across all the belligerents. The shared framework of the EU did not dissolve their socio-economic development into a single entity but rather provided the pattern for their collaboration as non-belligerent societies. This, then, renewed them as nations and did not dissolve them into a single entity. It gives the EU a quite different feel if you see it as enhancing its member nations as nations, rather than undermining them.

The second was a forensic analysis of the inner capacity of the EU, in generous review of Milward, by Perry Anderson (reprinted in his The New Old World in 2009). He identifies the political process that created the European Union whose chief architect was Jean Monnet. Anderson quotes Monnet as saying, “We are starting a process of continuous reform that can shape tomorrow’s world more lastingly than the principles of revolution” and he describes this as “incremental totalization”. Monnet’s strategy is an alternative to Leninism. It sets itself an unparalleled, ambitious objective “a democratic supra-national federation”. It then goes about achieving this “enterprise of unrivalled scope” through “drab institutional steps” that relied on “narrow social supports”.

In Britain I was being told that it was impossible to achieve anything as modest as a written constitution without a violent revolution or a war. Yet here was a process with far bolder aims achieving them in times of peace. It was surely an example for anyone on the Left: a process that did not bend to the winds of change but stood and generated them. Roberto Unger argues that the Left must stop being conservative and become utopian while having the imagination to invent the small, immediate practical steps that can take us on the way to a goal that makes us all fully human. Monnet’s method shows how this can be done. Not by the sleight of hand and denial of the Mont Pelerin gang, plotting their triumph of the market, but by an open declaration of a political goal. (That the EU too was captured by Hayekian neoliberalism is not the point: indeed you could argue that its obvious crisis is due to the incompatibility of these two forms of transformation).

There is a profound revulsion in the British Conservative party to the EU and its entire works shared by both those wishing to Remain and those for Leave. This is because all Tories desire to minimize change to our political structures – their core project is to conserve. But the whole point of the EU is to move things on, to build new institutions and define anew how power operates and to share sovereignty. This does not necessarily mean the replacement of the nation-state by a euro-super-state but it must mean, indeed it is meant to mean, the practical, moral and psychological ending of Europe’s antagonistic old regimes – of which both Hitler’s empire and Britain’s were examples. All Tories are agreed they cannot participate in this “unBritish” project. Given the EU’s size and influence and role in supporting corporate power, one wing of the Conservative party wishes to exploit it. In Cameron’s language, to retain a “special, best of both worlds” relationship so as to lever the UK’s influence in global affairs. The other wing fears that such blatant corporate sycophancy risks the loss of traditional loyalty and prefers a different wager: to rely on British skills as a global Singapore. Both wings abhor the Monnet project of shared change and want no part in it. One day an English Left will be born that can grasp the opportunity that the European process offers.

But can there be such a thing as a “democratic supra-national federation”? As so many are slagging off the EU at the moment it is important to salute its democratising achievements. These were not just to create a zone of peace after 1945 where there had been war, genocide, firestorm bombing of civilians (especially by the allies) and forced labour on a catastrophic scale. The EU reversed fascism in Spain, Portugal and Greece in the 1970s, supported the democratization of Eastern Europe in the 1990s, and raised human rights standards everywhere. To give an example, rarely acknowledged in self-satisfied world of Westminster and the London media, the Northern Ireland peace settlement is a product of the Europeanization of Ireland as a whole including, however grudgingly, the Catholic and especially the Protestant communities in the North and the UK itself. (This myopia continues in the Brexit debate, with neither the official Leave nor Remain camp being able to acknowledge the intrinsic value of the European Union to British democracy in this part of the United Kingdom).

The EU has always been top down and suffered a democratic dearth. But when its actions removed impediments between member countries and population and abolished restrictions it created openness. This then received popular consent from publics across the EU who appreciated the way it made life better and increased horizons. But when the EU switched from negative actions that took down barriers to positive integration, establishing institutions, legal systems, regulations and indeed “citizens”, then its top down nature caused resentment and began to be experienced as an imposition not emancipation. Maastricht reinforced this. At the very moment that the end of the Cold War finally created an undivided continent ready for democracy, the leaders of Europe began to levitate themselves upwards, beyond the reach of the grubby hands of the demos.

The central issue, which demands a much fuller treatment than I can give it here, is the nature of nationalism in a multi-national and now digital world. Politically, the cardinal issue for the European Union is the relationship between nationalism and democracy. For some in the Brussels elite, the “mere” nationalism of “mere” nation-states is something that their long-term aim is to marginalize, as a feudal hangover. They have set themselves against the democracy of “narrow” nationalism, as they see it, and seek to replace it with public support for a united Europe “fit” for global competition. In effect such members of the euro-elite are wedded to up-scaling an old regime mentality. British Tories should not alone in opposing this, indeed it is essential that such opposition is not confined to right-wing, populist nationalism.

Another, quite different process has also been released by the EU, as in its enhancement of its member nationalities. The EU’s member nations have formally renounced important aspects of their sovereignty in order to enhance their national interest. Such a politics is only sustainable if their voting publics feel their lives and humanity improved by their participation in an EU that makes them feel European as well as and not instead of their national identity. Just as there are different levels of democracy and self-government, so nationalism is being re-imagined into a plural multi-layered form of patriotism. This has to mean, however, revitalising not replacing civic national power alongside European collaboration. Ideally, each European country would seek to protect the national interests of the others. In turn this means our concept of who we are as citizens becomes a plural rather than a singular identity.

If this sounds abstract it’s because it is hard to envisage until experienced. At the end of the nineties I became friends with Reinhard Hesse who lived the spirit of what I am trying to describe. He was a speechwriter and collaborator of Gerhard Schröder, who became Germany’s Social Democrat Chancellor. Reinhard was at home in French, English as well as Arabic. Profoundly a man of the Left, he lived in “the terrain of reality”. We discussed the creation and launch of openDemocracy with the aim of creating a space for a European debate. On 17 May 2001, Reinhard launched the brand new website’s “Europa Debate” with a witty and perceptive “Letter for Europe“. He argued that “something is not happening. We are Europeans on the ground. We are Europeans in our stomachs, as a succession of food crises has shown, but we are not Europeans in our heads”. His last article for openDemocracy, “Crossroads or roundabouts, where now for Europe?“, written in June 2004, just before his fatal illness was diagnosed, wrestles with this theme but under much greater stress, in the shadow of terrorism and the Iraq war. Consistently, he battled and scorned abstract Euroscelorotic language. He welcomed the British government’s recent announcement that it would put any proposed European constitution to a referendum, because for him Europe needed the peoples’ support.

Four months later I had the baleful task of speaking about Reinhard at the memorial meeting for him in Berlin, in front of the Chancellor. Losing, our key European advisor was a great blow to openDemocracy especially as a larger strategic setback was sinking in. At the start of the century when we were planning its launch I assumed that there was nascent European public interest in debating the continent’s democratic future, ready to take advantage of the new medium of the web. Not a “demos” but enough people like Reinhard, democrats committed to the EU and wanting a public forum, to create a self-aware “continental” readership. This was not to be. Even at a relatively elite level of those interested in current affairs the existence of a web platform did not overcome what James Curran calls “nationalist and localist cultures” in his “Why has the Internet changed so little?”

It is well and good to call for the EU to be more democratic. But if hardly anyone wants to be a democratic European it cuts no ice. There is only one alternative to spontaneous, organic demand from below in response to the new situation, namely the conscious creation and orchestration of such demand by dedicated advocates through persuasion and example. This needs funding and support necessarily independent of the EU institutions themselves. Apart from the outstanding efforts of George Soros’s Open Society Institute and Foundation, whose contribution to defending the civilization of the continent is without parallel (and whose Institute and Foundation support the work of openDemocracy), there were few organizations willing to act. There are many wealthy ones committed to worthy public ends, such as those affiliated to the European Foundation Centre with its programme of supporting democracy and debate. But as multilingual European journals and websites designed for the intelligent public and in need of only modest support have closed this century it is clear a significant abstention is at work, which has contributed to the present democratic vacuity of the EU process.

Perhaps the best way to see this is by comparison with the nascent bourgeoisie that initiated movements for national self-determination in nineteenth-century Europe and recruited the public into them, whether through trade unions or churches, or warfare. Today, there is no nascent Eurogeoisie seeking the dangerous support of the unwashed or even unwashed journalists to help further its influence. Early capitalist liberalism was up against absolutist monarchs and had feudal restrictions to overcome. It needed to enlist if not “the masses” certainly the skilled professional classes into becoming a patriotic public. This in turn needed a media. By contrast today’s Eurogeoisie has no need for popular consent, indeed the less of it the better. They are already in charge! Despite their fine sentiments real, actual democracy is seen as a potential “anti-European” enemy, a threat to the larger project, that is to say their own monopoly of it. It was precisely the frankness, the wit, the caustic realism, a writer’s sense of how things looked from below, which Reinhard’s skills exemplified, that they did not want! When it was needed most, the seedbed of European democracy was left to wither.

Lisbon and the end of the EU’s attempt at democracy

The absence of a lively, memorable trans-European debate was particularly egregious because this was the time, 2002-4, that the EU began the process of turning itself into a constitutional entity. A more robust institutional framework was needed for the eurozone (the euro was launched as a currency on 1 January 2002) along with rules for flexibility as ten countries (eight former communist ones plus Malta and Cyprus) were scheduled to join the EU in May 2004.

The Blair government, a keen proponent of anything that would make Europe a base for the projection of power and “world leadership”, backed the creation of a European constitution. To prove the British government’s strong support it sent one of the Labour party’s most pro-European MPs, Gisela Stuart, of German origin and representing Neville Chamberlain’s old constituency, as one of its representatives to the Constitutional Convention on the Future of Europe. Today she is the Chair of Vote Leave. Her exceptionally open and honestly traveled trajectory is prefigured in a report she wrote while the Convention, with its 105 members, was still in process. It is from a Fabian pamphlet and was published in The Guardian in December 2003. It is worth quoting as length because it takes you right into the way the EU was being refashioned:

I entered the process with enthusiasm […] But I confess, after 16 months at the heart of the process, I am concerned about many aspects of the constitution […] The most frequently cited justifications for a written constitution for Europe have been the need to make the treaties more understandable to European voters and the need to streamline the decision-making procedures of the European Union after enlargement. I support both of these aims. But the draft document in four parts and 335 pages in the official version, is hardly the handy accessible document to be carried around in a coat pocket which some had hoped for at the outset. From my experience at the convention it is clear that the real reason for the constitution – and its main impact – is the political deepening of the union. This objective was brought home to me when I was told on numerous occasions: “You and the British may not accept this yet, but you will in a few years’ time.”

The convention [has] brought together a self-selected group of the European political elite, many of whom have their eyes on a career at a European level, which is dependent on more and more integration and who see national governments and national parliaments as an obstacle. Not once in the 16 months I spent on the convention did representatives question whether deeper integration is what the people of Europe want, whether it serves their best interests or whether it provides the best basis for a sustainable structure for an expanding union. The debates focused solely on where we could do more at European Union level. None of the existing policies were questioned […] This Treaty establishing a constitution… will be difficult to amend and will be subject to interpretation by the European court of justice. And if it remains in its current form, the new constitution will be able to create powers for itself. It cannot be viewed piecemeal […] we have to look at the underlying spirit.

Little wonder that the official European spirit did not want websites biting at its heels. Gisela Stuart argued that any proposed constitution for Europe be put to a referendum and in April 2004 Tony Blair was persuaded by Jack Straw, then Foreign Secretary, to promise one – otherwise they would be defeated in the House of Lords if not in the coming general election.

The British decision forced the hand of president Chirac in France. Every household in France was sent their own copy of the final constitutional document. Shortly after the UK returned Blair as prime minister in early May 2005 (on a record low of 35 per cent of the vote), the French rejected the proposed EU Constitution by 55 per cent to 45 per cent on a turnout of 69 per cent; three days later, the Dutch were even more decisive and gave the constitution a thumbs down of 61 per cent to 39 per cent. Already alarmed that they would be humiliated in any referendum, a relieved Jack Straw phoned Blair to tell him the early news of the French result: there would be no need for the UK to consult its voters now the French had rendered the proposed constitution otiose.

The French and Dutch votes were the moment of truth for the European project. For the first time a full Treaty that was being proposed was put to people, to its own designated “citizens” indeed, in their respective countries to decide. The Spanish voted enthusiastically in favour. Then the twin rejection followed in two of the original six. Obviously, a profound re-think in Brussels was called for. It had to rise to the challenge to create the public debate essential to winning support for the integration it envisaged.

By luck, in Brussels, I went to see one of the most senior members of the European Council’s General Secretariat in his office shortly after the double referendum outcomes. He was shaken. The French vote against the proposed constitution was due to Chirac playing politics, he said, in effect already persuading himself that France had not really rejected it. But the Dutch! For Holland, the most European country of all European countries, at the centre of its trading networks, cosmopolitan and without great power pretensions of its own, to have turned down the European process so decisively… he shook his head in disbelief.

The result for openDemocracy was the most sophisticated description I have read of the four reasons why the EU is important but is not a super-state. In late June 2005, less than two months after the Franco-Dutch rejection, “What the European Union is” was published under his nom de plume of Simon Berlaymont (the name of the vast building housing the headquarters of the European Commission). Alas, the article’s purpose was to set out why it should not have been called “a constitution” in the first place, thus arousing the public and setting off demand for consultation:

The fact that the treaty was drawn up by a “convention” and that it calls itself (in big print) a “constitution” does not change the reality that it is an intergovernmental document: the title begins with the word “treaty”, in small print, but this is what it is. “Constitution” is a part of the excessive rhetoric of Europe that obscures rather than illuminates, and threatens when what is needed is reassurance.

This was the approach the mandarins of Brussels adopted to persuade themselves and Europe’s leaders that they could recycle the draft Constitution into a “non-constitution’ that could come about without referendums, using inter-governmental treaty change alone. If the peoples of the nations of Europe did not wish to change the way they were governed it was because they were trapped in the past; therefore the government of the continent would best be changed without consulting them. The outcome was the Treaty of Lisbon. Signed at the end of 2007 and coming into force in 2009, the constituent parts of the proposed constitution were spread out as amendments of previous treaties. Repackaged, the main change turned out to be the elimination of the word “constitution’. Giscard d’Estaing, the former French president who had headed the Constitutional Convention, could not resist winding up the English by gloating in The Independent that, “The difference between the original Constitution and the present Lisbon Treaty is one of approach, rather than content […]”

In terms of content, the proposed institutional reforms – the only ones which mattered to the drafting Convention – are all to be found in the Treaty of Lisbon […] There are, however, some differences. Firstly, the noun “constitution” and the adjective “constitutional” have been banished from the text […] all mention of the symbols of the EU have been suppressed, including the flag (which already flies everywhere) […]

“Simon Berlaymont” justified this disgraceful outcome in 2007 in a farewell to “Tony Blair and Europe“:

The virus of referenda is contagious. Blair caught it from a weak and divided Conservative Party that needed to avoid the responsibility for taking decisions itself. Later he found himself too weak to resist when they called for a referendum on the constitutional treaty […] Referenda are more associated with continental countries, and then not always with their most democratic moments. The virus then spread to France and the Netherlands; in France in particular it was always going to be difficult to resist calls for a popular vote on something calling itself a constitution.

There you have it, the judgment of the people is reduced to an infection; referendums are a virus.

Lisbon made the EU an independent legal entity, which it had not been before. It created a diplomatic apparatus in parallel to those of the EU’s nation-states. It charged the European Court in Luxembourg with the power to impose its judgments on all member governments. Whether this is “really” a constitution is sophistry. Whatever it is, it demanded the positive assent of the EU population, based on a coherent understanding of what it proposed. Faced with the Dutch and French rejections the apparatchiks of the EU should have accepted the peoples’ verdict and stood the process down until they had gained such consent. Instead, urged on by Blair, the EU abandoned democracy in favour of a capacity to project its power. Lisbon replaced all previous existing treaties, from Rome to Maastricht. Today, it is now the Treaty of the EU. With the decision to defy the peoples’ verdict built into it, the European Union has become a flagrantly undemocratic oligarchy. There is a direct line of descent from Lisbon to the German finance minister telling his counterparts in the European Union last year, “elections cannot be allowed to change an economic programme of a member state”.

In effect, the EU betrayed itself. So profoundly, it cannot survive in its present form. It was one thing, mistaken perhaps but honourable, to foresee the replacement of national nationalisms with a European patriotism, larger, more expansive, implicitly more civilized, in the long-term prospectus of Europe’s “ever closer union”. This vision of a “super-state” foresaw a European democracy, a power that won the active assent of the peoples of the continent, indeed without such energy and loyalty it cannot succeed if the idea is to compete with global powers such as the USA and China. This option has been foreclosed for the existing EU thanks to the way its institutions have been set up by Lisbon. A form of rule created in plain defiance of the popular will is not going to be able to recruit it, at least not without undergoing a deep transformation. If Brussels is a caterpillar intending to turn into a democratic butterfly the process of cocooning itself is going to be very painful indeed.

Some of its recruits can dream about it, though. I experienced one such idealization when, while the process of moving towards Lisbon was underway, Margot Wallström, the EU’s Vice President for Institutional Relations and Communication Strategy, launched Plan D for Democracy, Dialogue and Debate. It was about “Making your voice heard”. For me it came to demonstrate the futility of worthy calls for more democracy. Six “citizen dialogue” projects were created. The King Baudouin Foundation funded a massive exercise in participative democracy. This recruited a random selected, representative sample of Europeans to participate in a reflection on what the European Union should become – making their voices heard. James Fishkin, who had developed the methodology, and whom I knew from my proposal to turn the House of Lords into a chamber selected by lot, was one of those recruited to design the whole exercise. Tony Curzon Price was openDemocracy‘s editor-in-chief and with his generous interest in innovation he oversaw a big effort to cover the whole process, with Jessica Reed, J Clive Matthews and many others.

I went to watch one of the sessions in Brussels. A hall of citizens from across the continent sat in small groups, each around a table, supported by phalanxes of simultaneous translators. For the first time I felt that Europe actually was in Brussels. But what came of it? A massive and doubtless still fascinating “dLiberation Blog” on openDemocracy along with a shorter Citizens consultation blog and thousands more well intentioned words elsewhere. But not a dent on the EU itself, no particular advance towards democracy of any kind thanks to all the effort and expenditure, nor any measurable increase in wider public support. The exercised demonstrated a crucial fact about all attempts to make the EU as it now is more democratic. It is pointless to try and add more democracy to Europe’s lack of democracy. The “idea of Europe” sucked in energy like a black hole with results ordained to be invisible.

Among the reasons for this was the Euro, then in the background, pumping the boom; its undemocratic character waiting beneath its shroud for the crash of 2008 to scythe the young of southern Europe from employment. Wolfgang Streek, in Buying Time, the Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism (2014) captures the cultural implications of a shared currency created without democracy:

The society needed for this must have a high tolerance of economic inequality. Its surplus population must have learned to regard politics as middle-class entertainment from which it has nothing to expect. Its worldviews and identifications it must derive not from politics but from the dream factories of the global cultural industry, whose massive profits must also serve to legitimate the rapidly increasing extraction of surplus value by the stars of other sectors, especially the money industry. (p. 117)

DiEM25

What to do about an EU that has turned from a system of solidarity to one generating division and chauvinism as its dream-factories crumble? In 2012 I was asked by Neil Belton and Fintan O’Toole to contribute a chapter on Europe to the collection Faber were publishing, Up the Republic! I wrestled with the material for two months but could not resolve my own view. I found it intolerable for Europe to continue as it is doing but equally intolerable to be against Europe. I had experienced the fruitlessness of efforts at adding “more democracy’ to it and could not advocate that kind of reform. But a return to nation-states outside its framework was asking for reaction not republican self-government. I abandoned the effort, unable to resolve what a “republican’ approach should be for the EU.

This year a new analysis and call to arms for a democratic Europe has solved the problem, at least of where to start, thanks to Yanis Varoufakis. Far from sitting at a desk scratching his head about a chapter, he was propelled into the lion’s cauldron, the Eurogroup itself. He emerged badly gored but alive and defiant. Varoufakis personifies the rise of Syriza to power in Greece, thanks to its current prime minister Alexis Tsipras, an exceptional “political engineer”; the clarity of Syriza’s objections to the imposition of self-defeating austerity programmes by the Eurogroup; and the popular defiance of the EU’s conditions summed up by “Oxi”, the “No” vote supported by 61 per cent of Greeks in their 2015 referendum. Tsipras then felt obliged to capitulate, Varoufakis did not. Instead, after he resigned, as he explained to Michel Feher, he went round Europe in the wake of the debacle and found people had

a sense of foreboding, and a sense of concern, about what effect the crushing of the Greek government would have on them, their societies […] on the capacities of their communities to make decisions pertinent to their own life. [… S]oon I had this idea and scenario in mind: as Europeans we [must] harness the feeling that truly binds us together and allows us to redefine European identity on the basis of resistance […] We can harness that spirit of concern for locality alongside the concern for the globality of Europe in order to create an alternative. We can stay in Europe in order to challenge head-on the highly anti-democratic processes and institutions of the European Union, and we can salvage Europe and the European Union from it.

Out of this experience came DiEM25, a manifesto for a democratic Europe. I should declare a small interest: I was privileged to make suggestions to an early draft. But the basic argument of the long version had nothing to do with me and I can praise it unconditionally. After saluting the EU as a historic peace project, it nails its dark side:

From an economic viewpoint, the EU began life as a cartel of heavy industry (later co-opting farm owners) determined to fix prices and to re-distribute oligopoly profits through its Brussels bureaucracy. The emergent cartel, and its Brussels-based administrators, feared the demos and despised the idea of government-by-the-people.

Patiently and methodically, a process of de-politicising decision-making was put in place, the result being a draining but relentless drive toward taking-the-demos-out-of-democracy and cloaking all policy-making in a pervasive pseudo-technocratic fatalism. National politicians were rewarded handsomely for their acquiescence to turning the Commission, the Council, the Ecofin, the Eurogroup and the ECB, into politics-free zones. Anyone opposing this process of de-politicization was labelled “un-European’ and treated as a jarring dissonance.

The result “is to prevent Europeans from exercising democratic control over their money, finance, working conditions and environment”. The DiEM Manifesto adds, “the price of this deceit is not merely the end of democracy but also poor economic policies”. It is an increasingly familiar argument, that neo-liberalism or market fundamentalism is stealing the language of democracy to create a disenchantment with politics, as in Wendy Brown’s description of it as a “stealth revolution”. But in the DiEM manifesto this critique has ceased to be an academic analysis. For it emerges from the experience of the cauldron itself. Thanks to Greek defiance we have witnessed the brutal imposition of the “technical’ on the democratic. Behind the stealth we have seen the steel; as the confrontation exposed the policies and interests behind the financial mask of neutrality. Which means in turn that the manifestos call for making the processes democratic is also a call for honesty that could become popular.

The Monnet method of incremental progress towards an extraordinarily ambitious goal of European unification turns out to have been driven by a cartel consciousness. When bringing down barriers it was experienced as opening up Europe despite its closed procedure, as it made everyone more European. When, after Maastricht, it began to erect a machinery of its own centralized government, it began to treat national objections just as a cartel would: as a virus to be patiently but clinically exterminated.

The fundamental difference between the numerous worthy, Plan-D type calls for the EU to have “more democracy”, such as a better parliament, and the approach of DiEM is that DiEM 25 demands that the core institutions of the EU be replaced with a democratic heart transplant. The demand is cultural as well as institutional: the veil of technical neutrality must be pulled aside on economic decision-making to reverse the EU’s depoliticization of democracy.

Thanks to its late-modern construction in the era of market fundamentalism, the EU perhaps more than any other civic entity, seeks to put questions of the economy and therefore of equality “beyond’ politics and democracy. It is this defining process that DiEM 25 defies and aims to dismantle. It is a call to confront the absence of democracy not a plea for democracy to be tacked onto the absence.

My own view is that any such strategy requires the abolition of the monopoly of the euro as a single currency. It can continue to exist and be overseen by the European Central Bank, but on an agreed day all the eurozone countries should issue their own currency to float against the euro and restore flexibility to them. There can’t be an open economic and political process while societies of over 500 million souls, all of which are already proud democracies, have to relinquish all control of their money. It will also mean abandoning the aim of creating a single political-economic power that can exercise hegemony on a world scale as an equal of the USA, and China; the wet dream of Berlaymont towers.

What kind of organization is this DiEM25 with the audacity to harbour such thoughts, even if unofficially for mine have no particular standing? It was launched at the Volksbühne in Berlin on 9 February by Yanis Varoufakis and Srecko Horvat. It is greatly to their credit they propose an experimental process in which others will create it equally. Varoufakis had told Feher it will “evolve organically”:

DiEM is a movement. It is not a party, a trade-union, a think-thank or a conference. It’s a surge: a surge of European democrats who are moving together to seize control, to put the demos back in democracy at the European level, and to infect every nook and cranny of the EU with democracy. It is a totally utopian project, and it’s very likely to fail. But it is the only alternative to the awful dystopia that we are facing if we don’t do anything at all.

The launch saw a day of three intense, crowded sessions of discussion between activists from across Europe (the third of which was chaired by openDemocracy‘s editor-in-chief Mary Fitzgerald). A packed evening rally followed. The discussions mixed concerns and confidence: in many countries, especially Austria and Eastern Europe, it is the right that holds “the streets”; the danger of populism with the likelihood of deflation caused alarm; immigration is generating misanthropy. Well-articulated descriptions of the decomposition of traditional organizations, social democratic and trade union, provided the backdrop. But along with the defeat in Greece there was the success of Barcelona. Its deputy mayor suggested a new International Brigade to assist it and called for more “rebel cities”. This took the argument on to the commons and the potential political economy of a shared, progressive Europe.

Paradoxically, DiEM could gain more traction thanks to the bleak veracity of its vision than from any idealization of what is possible. In Berlin, Madrid and now across France with the Nuit Debout, it draws on the unruly energy of a precariat and its “digital natives” starting to experience themselves as a trans-European class. If DiEM can find and build an agency, to use a technical term, the as yet unknown form for organizing the surge may be found, drawing perhaps on the experience of the Sanders surge in the United States.

The Volksbühne launch rally in the evening brought together a unique alliance of speakers. Among many were Caroline Lucas, an English Green, Hans-Jurgan Urban, who runs Germany’s IG Metal trade union, with its 2.4 million members side by side with Anna Stiede of the Blockupy movement, a wonderfully incongruous pairing. Predictably it included some leftist ranting of the cock-sure kind I associate with a lost cause. But there was also Brian Eno in conclusion, reminding the hall carefully and emphatically that “democracy is for people who do not know what to think”, keeping the whole process open.

The promise of DiEM25 lies in the puzzle as to its nature, sidestepping usual categories. What makes it potentially influential is that it is a platform rather than a traditional “cause”, a space fit for digital times – a platform with a focus of course, setting out to re-politicize policy-making, especially in their economic and financial spheres, to bring back financial and monetary strategy to the reach of democracy. Such an open cause can become a springboard for projects and experiments that combat the marketization and de-democratization of power while networking across the European zones. Labour’s John McDonnell has made the young generation the centre of his call for Remain, rightly so; the test being if his party can embrace their culture. For we will not achieve the democratization of the EU by traditional “party political” means for its structures are fully prepared to repulse them, as Varoufakis has argued.

The democratization of the EU is an extraordinarily ambitious goal. The only way of achieving it is to turn the “Monnet method” against the monolith that Monnet’s project has become: to hold to the overarching ambition while creating small realities that shape the long-term outcomes that can achieve it, strengthened by the hope of a new generation. Also, we can be emboldened by the weakness of the EU. As long ago as 2012, Martin Wolf writing in the Financial Times concluded, “The principal economic force now keeping the system together is fear of a break-up”. This is far from the strongest of foundations! It exposes both the role of the euro and the way it is run to a potentially successful challenge.

To return to the UK’s referendum from this perspective is to ask what is the next small step to take. If your concern is simply Britain then Boris and his band of Brexiteers have the better argument, indeed the only argument with any patriotic integrity and republican virtue (of course, the UK is likely to be poorer and they should not pretend otherwise). ‘Republican’ in the sense that Walter Bagehot, founder of the Economist and author of The English Constitution, asserted, when he showed that behind the decoration of monarchy the Kingdom is a better-governed republic than the United States. The Brexit camp cares about how we are governed, the nature of our democracy and they scorn the undemocratic nature of the EU. On these issues Cameron, Osborne and their fellow Remainers and collaborators like Andrew Marr are silent. They know they are selling the country to the global corporate forces, which are funding their campaign and coming out openly in support of it; this being no “conspiracy”. It applies to their corporate Labour bed-fellows too, whether Blair with his two-million-pound-a-year-fee from JPMorgan Chase, or Peter Mandelson, friend of Deripaska and company. Their alarm, which is evident in the exaggerated claims of disaster as to what will happen to the UK’s economy if the people vote Leave, is indeed for them a genuine worry about the end of the world – as they know it. Their concern is not so much with what might happen to Britain, the British people, the country’s security or ability to go to war. Instead, just look at the rise of inequality they and their corporate caste have overseen since 1997 and its crippling impacts and you can see the process they are defending. If there is a sense of panic in their warnings it is over losing their place in the cocktail parties of the international power elite – to which they genuinely see “no alternative”.

If, however, you feel in part European, if you regard yourself and your concerns for your country, whether England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland or just plain Britain, as something that also extends to our continental home with France, Italy, Spain and Germany not to speak of Holland, Norway, Poland and Greece to choose just eight examples from 30 plus in and around the EU; and if you hold such feelings as a democrat who wants a more equal, less money obsessed continent, then why would you want Britain to be run by the Brexit crowd and their hedge fund supporters, setting themselves in competition with the EU, under the vile, authoritarian conditions of British winner-takes-all politics? Especially when the failures of the EU mean it will have to change.

The coming fight for Europe is our fight. Lose it and we lose it here across the UK. Whether we Leave or Remain, if the EU turns irrevocably sour, neo-liberal, authoritarian and chauvinistic, so will the British Isles. Across our continent, an EU that regards the judgment of the people as a form of virus has lost its legitimacy. It is ripe for challenge. Think this, and DiEM 25 creates an open platform for creation of a democratic Europe of democratic nations. The EU has already been created through Monnet’s method of incremental yet transformative reform. Now it is the peoples’ turn to apply this peaceful but thoroughgoing approach to take back our European economy from corporate power. Think this, and roll up your sleeves for Remain.

This is an abridged version of Chapter 8 of Anthony Barnett’s ongoing book project. Every week since 22 March 2016, a new chapter of Blimey – it could be BREXIT! has appeared in openDemocracy.