For a strong start into the second season, we talk about corruption in the EU. In the basement of the European Parliament we talk Italian mafia, Orbán’s son-in-law, and the misuse of public funding in member states with MEPs.

It’s 100 years since Mussolini took political control of Italy. Given a period of violent tensions across large parts of Europe after the First World War, what specifically lay behind the rise of fascist totalitarianism? And how does the Duce’s leadership compare to that of other contemporary authoritarianism?

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič interviewed Richard J. B. Bosworth, who has written extensively on Mussolini and fascist Italy, for Slovenian Eurozine partner journal Razpotja.

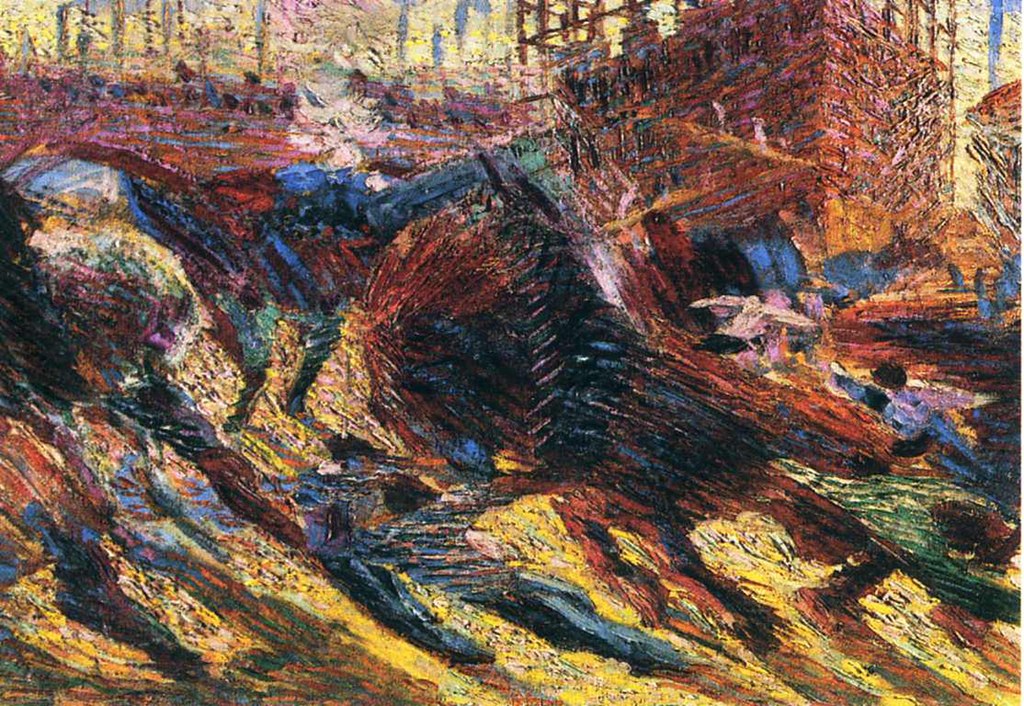

The City Rises 2, Umberto Boccioni, 1910. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: This year, we remember the hundredth anniversary of the March on Rome, which marked the beginning of the first fascist regime in history. In Slovenia, two years ago, we commemorated the hundredth year since the anti-Slovene pogroms in Trieste. There is, therefore, awareness that fascism was a political factor in the ‘eastern borderlands’ of Italy before the Partito Nazionale Fascista (National Fascist Party), formally established in November 1921, came to power a year later in Rome. How important was the mobilization against national and ethnic minorities for the rise and success of Mussolini’s political project?

Richard J. B. Bosworth: You are right to remember the burning of the Narodni Dom (National Hall) on 13 July 1920, justified by Francesco Giunta, the local fascist boss, who described the struggle of the Fasci di Combattimento (the forerunner organization to the PNF) within Italy as a struggle between one Italian and another, while ‘the struggle in Trieste is contested between Italians and foreigners’. Four weeks earlier, Mussolini had stated, ‘we must cleanse Trieste energetically’. The Duce was an able and inventive journalist; he came up with a metaphor of ethnic conflict that was to have, and still has, a terrible history. It wasn’t for nothing that Triestine fascists made up 18% of the party’s national membership early in 1921.

Italy was not the only country confronted with such issues at the end of the First World War, which began as a conflict between empires but concluded, or rather variously continued after 1918, as a conflict of nation states. Wilsonian self-determination may have sounded like an American pledge to freedom. But throughout the inter-war period, every European ‘nation’ was confronted with the problem of ‘foreigners’ (to use Giunta’s word) living within their borders and co-nationals living in other states. Liberal Italy entered the First World War with an ‘irredentist’ aim, in other words, pioneering the idea of a nation state that would rule over all Italians – easy words with difficult and, in fact, murderous results.

The other face of Italian Fascism, as it rose so rapidly to power, was not ethnic but about class conflict. Across the Po Valley, Tuscany and Umbria, fascists multiplied in 1921-2 to repress newly unionized peasants and destroy the ‘unpatriotic’, ‘Bolshevik’, socialist movement. The PNF was backed, either directly or indirectly, by landowners, industrialists, the Vatican, the army, the monarchy – the rich and powerful of liberal Italy. Some aspects of this class war would prove complex after 1922. But in its early days, fascism was unquestionably an anti-Marxist movement and that purpose outweighed its ethnic aims.

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: We often think of fascism as the movement which introduced violence into politics. But the years following the First World War were characterized by widespread political violence across Europe, from Ireland to Bulgaria, from Barcelona to Helsinki. Can we see fascism as a movement which managed to capitalize on this new reality more successfully than its adversaries?

Richard J. B. Bosworth: Yes. As I mentioned before, armed conflict did continue across central and eastern Europe (and beyond) after Germany and Austria-Hungary admitted defeat in November 1918. For one thing the Romanov Empire had collapsed into multiple civil wars, with intervention from France, the UK and the US, as well as a complex of German forces. But violence was indeed everywhere as the new world of nations came into existence. In the UK, for example, there were vicious conflicts in what was becoming Eire (and Northern Ireland), with a per capita death toll greater than the 3,000+ people who died in the years of fascist violence in Italy between 1919 and 1925. Mussolini’s speech on 3 January 1925, when he announced his dictatorship, openly endorsed whatever violence his followers had engaged in and did indeed, to some extent, separate Italy from other states. But plenty of nations were, or would become, dictatorships of some kind. For example, much history still praises Kemal Atatürk’s rule in Turkey where the death toll of the peoples of his country was vastly higher than in Italy.

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: A chapter of your book on Mussolini’s Italy is entitled ‘Becoming a fascist’. How did one, back then, become a fascist? Who were the early fascists? Which political and social background did they mostly come from? What were the most common dynamics of radicalization?

Richard J. B. Bosworth: Generalization about complex human beings is always a fraught matter, but it can be agreed that all of those who joined the FIC and then the PNF had favoured Italy’s idiosyncratic entry into the First World War. They were therefore likely to agree with the extravagant poet, Gabriele D’Annunzio’s complaint that, in 1919, the nation faced a ‘vittoria mutilata’, a mutilated victory. Most had served in the war and fascist leaders in various localities had usually been of officer rank, generally junior officer rank. Giunta (born in 1887), for example, was an infantry captain, having been a supporter of the Nationalist Association (founded in 1910) before 1914; while the government was contemplating which side to join, and when, between August 1914 and May 1915, he was an interventionist, agitating for Italy’s entry into the war against Austria-Hungary. Mussolini (born in 1883) was only a non-commissioned officer, held back in his military career by his pre-war campaigns as a socialist and unseemly personal life. His younger brother, Arnaldo, a man of business, petty bureaucrat and pious Catholic, automatically became a sub-lieutenant, when he was conscripted late in the war. The youngest fascists were sometimes too young to have fought in battle but were inspired by the nationalist myth of the war and of war-making. Not for nothing would the PNF ‘anthem’ become Giovinezza (Youth).

Fascists were unlikely to be working class or peasants, at least of the poorer and unionized segment, since they had already been politicized into the socialist party/parties: the Partito Socialista Italiano, founded in 1892, split into three separate groups during the fascist rise to power. Most fascists sprang from the middle or lower-middle classes. The movement was much more formidable in northern than southern Italy and fascists found their homes in the numerous, beautiful, yet economically troubled Italian cities. University students, still confined to a social elite, were likely to favour fascism. To a considerable degree, the equation ‘nationalist fathers, fascist sons’ holds true for 1919-1925 Italy.

I’m not sure about the term ‘radicalization’. In 1921-2 Mussolini led his movement and party into quite a few compromises with the liberal establishment. From a republican, he turned monarchist. From an anti-clerical, he sought accommodation with the Church, even having a church wedding with his wife, Rachele, with whom in his socialist days he had lived in comradely disdain of officialdom. From advocating taxing war profiteers, Mussolini preached an economic policy for a time that sounded politely liberal for the rich.

Yet again, I should be clear that these early fascists were very violent. A typical fascist action in 1921, say, was to take a truck, armed with modern accoutrements (provided free by rich local liberals, the police or the army), to a socialist meeting place to devastate it, forcing their enemies to drink castor oil, with the humiliation that would follow. Deaths were always a possible outcome of these raids: sometimes of fascists themselves, but more commonly of those whom they had attacked.

Liberal Italy was certainly not what we would understand as a democracy. It did have a parliament. But the legislature was controlled by jostling factions and not by mass parties. Elections did occur and, in 1913, suffrage was extended to most men (women play little part in the fascist story). But results could be manipulated by local prefects on instruction from some powerful man either in Rome or in some provincial town, and those who opposed the existing situation could be beaten or worse. Not for nothing was the Italian South a region where the Mafia, ‘ndrangheta and Camorra were beginning to flourish. The murder rate in Italy was a lot higher than in Britain, France and, I imagine, in Austria-Hungary. Fascism did have original features, and its preaching and practice of violence should never be ignored. Yet, it was and remained, in many senses, ‘Italian-style’ rather than what we conjure into existence today – when an easy, all too easy, use of the word ‘fascism’ is applied to people whom we don’t like.

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: What were the factors that enabled Mussolini to quickly consolidate power, especially compared to other authoritarian attempts in Europe in the 1920s?

Richard J. B. Bosworth: As you mention, there were many authoritarian regimes in Europe at the time: Portugal, Poland, Hungary and Turkey followed different paths, but all of them saw a successful consolidation of power in dictators’ hands. Mussolini had the advantage that he had won over the army, the King, the Vatican, business and much of the once Italian-style ‘liberal’ establishment. He was adroit in playing off factions within the PNF and in rusticating men like the radical Roberto Farinacci and the more elite Italo Balbo, while also keeping a large personal archive of the details of corruption among fascist bosses.

By 1933-5 there were signs that the regime was tiring, but Mussolini found a solution in waging a brutal war on Ethiopia, therefore ‘avenging’ the Italian defeat of 1896. Even Benedetto Croce, in his own mind, the most purist of liberals and ‘anti-fascists’, donated his senator’s gold medal to the national cause. About half of the million victims of fascism were from its empire: Arabs and Berbers in Libya, and the many peoples of Ethiopia who were bombed with poisonous gas and had their villages burned and strafed by an Italian air force that faced virtually no opposition. But Italy almost entirely lost its empire by 1945 and so avoided the problems of decolonization that beset postwar Britain, France, Portugal, Spain and the US. Such a clean cut in national history, which also meant the end of any illusion that Italy could remain even the ‘least of the Great Powers’, helped Italian historians and the public avoid any serious confrontation with the country’s murderous imperial record.

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: You mentioned that Italian Fascism was essentially an anti-Marxist movement; simultaneously though, unlike Horthy’s contemporary counter-revolution in Hungary or Franco’s later anti-democratic military uprising, it relied heavily on some of the most secularized sections of society (including a tiny Jewish minority) and had important support in the artistic avant-garde. Can you say something of this ‘modernizing’ aspect of the fascist movement? The analogy with Atatürk seems interesting in this regard.

Richard J. B. Bosworth: Yes. Mussolini had grown up as a socialist, heavily influenced by his father, Alessandro, who was a socialist activist in the province of Forlì, Emilia-Romagna. It can be argued that Benito was, at least until 1932, psychologically in competition with his father (who had died in 1910), attempting to prove that he was not a mere reactionary like Horthy. He always sought some sort of mass base.

Once he became a dictator, he destroyed all Catholic and Marxist trade unions, banned the expression of anti-fascist ideals in the press, demanded the dissolution of rival parties to the PNF and favoured the work of the secret police. More than 10,000 Italians were confined to Italian islands and the South, and banned from pursuing their previous work. Tens of thousands of others were given official warning that they risked such a fate. Fascist Italy was a police state. We know from Mussolini’s events diaries, recently made available in archives, that Mussolini saw Arturo Bocchini, his chief of police, almost every day as one of his first appointments. From 28 October 1925, Italy was declared a totalitarian state where ‘all is in the state, nothing is outside the state, nothing and no one is against the state’.

The regime was inventive with its propaganda. As I’ve said, Mussolini was a very able journalist, and he and his aides managed to make the Duce what we today call a celebrity. His ‘fame’ didn’t contest the other part of the world where 1920s’ propaganda was triumphing: Madison Avenue, where ‘I shop therefore I am’ was being sold as the key modern development.

Yet again, when it came to tyrannical practice, the police operated ‘Italian style’. Bocchini, who died in 1940, was a career bureaucrat who could scarcely have been more different in personality and attitudes from Heinrich Himmler, Hitler’s ideology-driven policeman. Those confined almost always tried to get their sentences reduced through family or other influence. Italy, in other words, was a police state where many people went on thinking that the law was open to manipulation and preference, to what might almost be called Italian-style ‘corruption’. Such qualification of ‘rigour’ can be found in many aspects of fascist Italian life.

Giacomo Balla, Sculptural Construction of Noise and Speed (1914-1915, reconstructed 1968), at the Hirschhorn Museum. Image via Wikimedia Commons

If we turn to the support that Mussolini received from some avant-garde circles, we must first understand that the majority of Italian intellectuals – Marinetti and the Futurists first and foremost – wanted intervention in the war, and frequently volunteered for service. They had much in common with the fascist movement. Mussolini himself was an aspiring intellectual from the provinces who expected his wife to address him as ‘professore’ (he had teaching qualifications from the University of Bologna and had taught in primary schools).

Many other avant-garde figures found it in their interest to support the Mussolini dictatorship and he loved to be celebrated by them. For example, Ezra Pound remained a fan until 1945. When he met Mussolini (the Duce filled up his days with interviews), he was greeted by a dictator who assured him that he had just read the very difficult Cantos and found them excellent. A book of Pound’s poems lay open on the dictator’s desk. But this was almost certainly mise-en-scene. There is no proof that Mussolini had actually read Pound let alone ‘understood’ him.

After the triumphant Decennale, ten years after the March on Rome, Mussolini was rapidly outpaced in purpose and achievement by Hitler and the Nazis. Some sympathizers were put off by German antisemitism and other fanaticisms, and drifted away from what was being called ‘fascism’. Especially during the Second World War, quite a few young intellectuals threw off their fascist black shirts and became communists, socialists or liberal democrats.

One other aspect of the regime’s supposed mass base was the much propagandized idea that it was a ‘corporate state’. Such a system meant, at least in theory, that economy and society should function with unity between the classes, in the interest of the nation. There was a large fascist union and the big business organization Confindustria had to add fascista to its title. This structured class collaboration today might seem to be followed successfully in a country such as contemporary Germany. The problem with fascist Italy was that words didn’t have certain or full meaning. Most historians today agree that the economy didn’t function how officials said it did, and the fascist welfare state was riddled with corruption and contradiction. Again, the Second World War was a ‘test’, which the regime calamitously failed, despite Mussolini’s speeches and party proclamations that had harped on for a generation about the country’s militancy.

And the parallels with other authoritarian chiefs? In 1932 it was still easy to wonder whether the rulers of Austria or Hungary, or the Baltic states, or Portugal, or Greece, or Turkey were following an Italian fascist course. There were even claims, which continued until 1935, that Franklin D. Roosevelt was just another Mussolinian. The Duce himself feared that FDR had more power than he did. In the 1920s, Mussolini had generally argued that fascism was ‘not for export’. In 1932 he stated instead that it was ‘the doctrine of the twentieth century’. But, once again, that propaganda line faded once Hitler took office a year later.

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: In one of your books, you raise a seemingly paradoxical question: Was Mussolini a strong or weak dictator? The question addresses the issue of personal power vis-à-vis institutional inertia, both at a party and state level. What kind of dictator was Mussolini then? What role did his personality play in the day-to-day administration of his government?

Richard J. B. Bosworth: Mussolini was undoubtedly the dominant figure in his regime, a real dictator. Yet, the aphorism used by Ian Kershaw in his studies of Nazism, whereby Germans ‘worked towards the Führer’, doing Hitler’s bidding without being told, contrasts with Mussolini who, in many senses ‘worked towards the Italians’, pursuing policies and attitudes that would not offend too many of his subjects, as well as changing and changing about.

Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič: This leads us to the notion of ‘totalitarianism’ which has raised a lot of polemics in the last decades. It is often forgotten, however, that the term was first popularized (and maybe even coined) by Mussolini himself. How well does that label fit his regime, though? And do you think this is a useful term of analysis?

Richard J. B. Bosworth: Yes, the regime called itself totalitarian. Yet, it didn’t really abolish class, regional or gender difference, or that between one country and the next. It did very little to infringe the workings of the Italian family, probably the most meaningful institution for many. It did little to check their Catholicism. Despite the regime’s propaganda, fascism didn’t really achieve a cultural or social revolution.

Today’s North Korea is a far stricter totalitarian state and society than fascist Italy ever was. Even where I am in the UK, with endless words now being poured over Queen Elizabeth II’s death that are far from any reality, it would seem that small instances of totalitarian thought can pop up anywhere and at any time.

Published 26 October 2022

Original in English

First published by Razpotja

Contributed by Razpotja © Richard J. B. Bosworth / Luka Lisjak Gabrijelčič / Razpotja / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

For a strong start into the second season, we talk about corruption in the EU. In the basement of the European Parliament we talk Italian mafia, Orbán’s son-in-law, and the misuse of public funding in member states with MEPs.

Eurocommunism at first seemed to offer a strategy for socialist transformation in keeping with the complexities of contemporary western European societies. But by the mid-1980s its momentum had dissipated, leaving communist parties in deep crisis. Despite its political failure, however, Eurocommunism could also claim important achievements.