Russian refugees influenced Istanbul’s cultural life from the 1920s despite the Turkification policies of the new republic. The Sevastopol-born sculptor Iraida Barry’s life in exile and love for the city is a piece of this history. However, admiring the Russian diaspora shouldn’t have meant demeaning others – as ended up happening in US press. Ayşe Kadıoğlu revisits a life exiled to Istanbul, while longing for the heartbeat city herself.

After the purges by Bolsheviks in Sevastopol that resulted in the killing of her godfather and the man named Pavel Nikolaevich Kondratovich whose romantic interest in her gave her a smile with a racing heart, she moved to Odessa in 1918. Odessa was controlled by the French and Greek troops until April 1919 during the allied intervention in the Russian Civil War on the side of the Whites. Some members of the Russian aristocratic elite began to arrive in Constantinople when the allied forces abandoned Odessa in April 1919 in the face of the impending Red Army as well as pro-Bolshevik paramilitary groups and the rise of the typhus and cholera epidemics.

Iraida arrived in Constantinople in 1919 before the first big wave of refugees from Odessa when it was finally taken by the Bolsheviks in February 1920. The second wave of Russian refugees came right when the White troops led by General Anton Ivanovich Denikin were evacuated from Novorossiysk in March 1920. These troops were mostly manned by Cossacks who were known as the loyal supporters of the Tsar. The evacuation of Novorossiysk was catastrophic. Many officers could not board the ships and committed suicide lest they be captured by the Reds. By April 1920 Baron Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel assumed the command of the remaining White troops in Crimea. Although he launched a new offensive in June, the White troops were defeated by November 1920. This was followed by the third and by far the largest exodus of Russian refugees from Sevastopol to Constantinople in November 1920.

An article by Martyn Housden refers to the Study Conference on the Question of Russian Refugees held by the League of Nations on August 22, 1921, where it was expressed that 130,000 people arrived in Turkey on the shores of Bosphorus and the Gallipoli peninsula. Some were placed in the refugee camp that was established on the island of Lemnos in the northern Aegean while the French tried to settle some of the refugees in Bizerte. An eye witness in Constantinople, cited in Housden’s article recalled ‘watching seventy-five ships carrying Wrangel’s people towards the city.’ In his piece published in The New York Times (December 4, 1921), Elmer Davis described the situation in November 1920 as follows:

‘Men, women and children, soldiers and civilians, swarmed aboard the ships in Sebastopol harbor – French, British, Russian, American ships –, anything that might take them away. Ten thousand of them crowded into a single Russian battleship – most of them carrying with them their jewels, the family silver, miniatures of their ancestors, watches, fans, furs – anything that was of small bulk and considerable value, anything that had a sentimental interest and could be carried away –trinkets and souvenirs of a better time.’

Davis indicates that 80,000 soldiers and 35,000 civilians escaped on 111 ships. Men who were there had the impression that General Wrangel was the last man aboard the last ship. Elmer says although this may not be literally true, it was true in spirit and there was great respect for General Wrangel. The American Red Cross assumed a big responsibility in providing for the civilians.

Iraida and Albert Barry’s marriage ceremony took place when Istanbul was under the occupation of the British, French, and Italian forces and during this intensified exodus of refugees from Russia who were fleeing the Red Army.

I sat down to write this essay in mid-April 2020, during the coronavirus lockdown in New York City. I normally live in Istanbul. I was spending the academic year at Columbia University as a visiting scholar when I first came across the Iraida Viacheslavovna Barry Papers.1 I was immediately drawn to the story of Iraida Barry against the backdrop of a very different Istanbul.

Once, I was asked to describe Istanbul with one word. My immediate answer had even taken me by surprise; it was ‘heartbeat’. Istanbul is a heartbeat city with an intense rhythm and once it gets under your skin, you are forever at its mercy. Hence, as a woman with a deep-seated feminist consciousness, my encounter with the story of this adamant Russian woman, a co-citizen of Istanbul, immediately filled me with the responsibility of telling her story.

This was inevitably the story of another Istanbul. It was a story that was laden with love; both among its characters and for their city, Istanbul. To me, the only conceivable love story that could be narrated during the time of coronavirus inevitably involved the people of a bygone era whose lives remained hidden in archives. Below, I divulge their stories in an endeavour to write about love at the time of coronavirus; an endeavour that also reflects my longing for the heartbeat city.

A shared fascination

After my encounter with the Iraida Barry papers at the Bakhmeteff Archive at Columbia University, I soon discovered that I was not alone in my fascination with her story. There were many others both in Istanbul and at Columbia University who had already researched her life as well as her Istanbul years at that particular juncture in history. Iraida Barry’s photographs archive is in the private collection of Cengiz Kahraman in Istanbul. In an interview with him in 2016, Kahraman talks about how his encounter with an album twenty three years ago prompted his interest in being a collector. He has acquired what he expresses as ‘a corpus…with a growing number of photographs, information, diaries, journals and letters.’

Gül Dirican has published moving essays about Iraida Barry in the late 1990s. Iraida Barry’s family friend Marina Dimitruli Logan of Brookfield, Ohio sent a very informative letter to Gül Dirican (dated June 21, 1999) that can be found in the archives at Columbia University. Some of the research endeavours are still ongoing. A few months ago, Valentina Izmirlieva and Holger Klein, both professors at Columbia University gave a lecture that alluded to Iraida Barry’s life and Istanbul’s Russian moment.

Most of the documents at the Bakhmeteff Archive are in Russian and therefore, I could not read them. They contain manuscripts of Iraida Barry’s father in Russian. It is also possible to see pages long exercises in English vocabulary. Iraida’s father practiced to read and write in English extensively after moving to the United States. Iraida too was mostly writing in Russian. Yet, she was also proficient in French and English. There are letters that she had written and received in these languages in the archives. She also wrote in Turkish, especially when she engaged in official government business such as applying for Turkish citizenship.

Iraida’s story

Iraida Viacheslavovna Kedrina (1899-1980) was the daughter of Elizaveta Vasilievna Muravieff and Viacheslav Nikonorovich Kedrin (1869-1951). Her parents were divorced in 1913. Her mother was remarried to Count Boris Muravieff until 1932. Her father emigrated to the United States in 1918 and her mother, after initially moving to Paris, joined Iraida in Constantinople after 1932. Iraida’s mother was known to the family with the nickname Baboushka (Grandma) Lika. She was described as a lively lady by family friends. Iraida believed her mother descended from the Nelson-Hirst family in England. In fact, she corresponded with the Managing Editor of the genealogical publisher Burke’s Peerage in London, Mr. L. G. Pine in 1953 and 1954 in order to confirm her mother’s lineage. In her letter to Mr. Pine, Iraida wrote: ‘I cannot resist the temptation to send you these photos of Lord Nelson and my deceased mother. For me whose hobby is sculpture, the similarity in the construction of face in both pictures is striking.’

Iraida’s father was a Captain in the Imperial Royal Russian Army. He emigrated to the United States where he got married to Maria Mikhailovna Kedrina, a Russian ballerina who managed a ballet studio in Santa Barbara, California. Iraida corresponded regularly with her father and her stepmother. She also visited them in the late 1940s. I came across a telegram in the archives that was sent to Iraida’s Istanbul address on May 24, 1951. It contained the short but painful words in capitals: ‘PAPA PASSED MAY 24 MORNING LOVE MOORA.’ Moora (or Mura) was the nickname that Maria Mikhailovna Kedrina used in her letters to Iraida.

A year after her father’s passing, Iraida was once again corresponding with the editor of a magazine that was published in Lausanne. The magazine called L’illustré had published a piece on the origins of Russian aviation. Iraida, who was undoubtedly suffering the recent loss of her father, sent a note to the readers’ comments section along with a photo of the students of the first Russian school of aviation. In her comments, she clarified that her father was the chief of this aviation school. The school was originally located on a field close to Sevastopol that was called Koulikavo and was later transferred to Katcha, north of Sevastopol. She described how, as a little girl, she once watched his father’s plane crash land on the field giving him a broken leg and causing a lot of anguish for her. She added: ‘please accept my respectful greetings and the expression of my hope that your newspaper – which to my knowledge is the only one that tries to trace the history of the beginnings of Russian aviation – insert these details’ (my translation from French). The magazine published her comments along with the photo.

I closed my eyes and thought about this woman from Sevastopol sitting at her desk in Mısır apartmanı, a landmark building in Istanbul. There she is… turning the pages of a French magazine and seeing a piece on Russian aviation in the October 16, 1952 issue, less than a year after her father’s passing in Santa Barbara, California. She is noticing that the information about her father’s role in the founding of Russian aviation is missing and she takes it upon herself to set the record straight. This was the moment I understood the dire significance of accurate historical records for those who lost everything that was hidden in their childhood memories.

When Iraida and Albert got married, Albert Barry was a well-known dentist with high profile patients. They lived in Mısır apartmanı on 303 İstiklal Street (formerly Grand Rue de Pera), Istanbul. They were at the heart of Pera with its continuous heartbeat. They spent the summers in Burgazada, one of the Princes’ islands of the Marmara Sea. They also had a place on the hills of Büyükada, the biggest of the Princes’ islands, which they used on weekends. Albert owned a car (a Studebaker) which gave them the freedom to visit distant parts of Istanbul, including the Belgrade forest, Yarımburgaz Cave, Caddebostan Beach, Beylerbeyi, Akıntı Burnu, Bebek, Rumeli Hisarı and Sarıyer. He also had three boats, which the family referred to as ‘the fleet’.

Iraida and Albert’s dinner table at Mısır apartmanı was always receptive to many guests. Those who worked in Albert’s dentist office dined and had high tea in their residence on a daily basis. Albert’s dentist office and their residences were on different floors of Mısır apartmanı.

Their residence was on the top floor with a large terrace. Iraida used parts of the terrace that was enclosed in glass as her sculpture studio. Quite on point, Mısır apartmanı is host to many art galleries today, with art viewers lined up in front of its old elevator on opening days of new exhibitions.

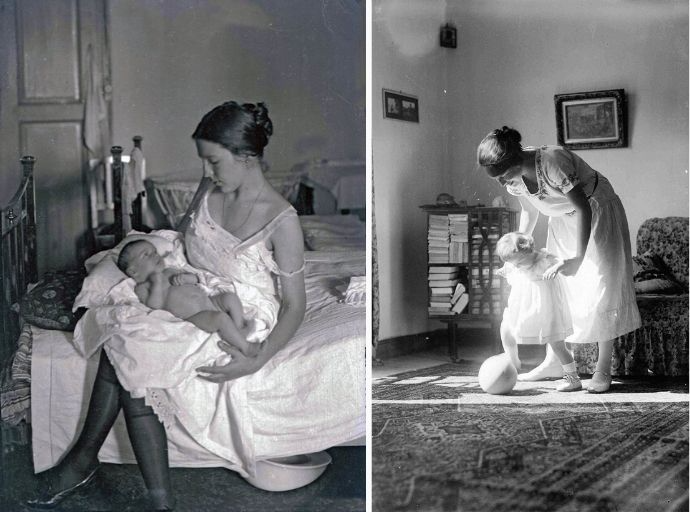

Iraida and Albert’s daughter Elizabeth (nicknamed Boba) was born in 1922. It was a breech birth with complications that resulted in cerebral palsy with a serious visual impairment as well as the paralysis of one arm and leg. Iraida wanted to give birth in a hospital. Albert’s mother insisted that the birth took place at home for no Barry was delivered in a hospital. The birth complications left Albert feeling guilty and had its toll on their relationship. They became more and more distant. In fact, when Iraida wrote her autobiography titled Mirror Shards, she told her story from the angle of all the men she knew in her lifetime. However, she did not devote a section (or a mirror shard) to her husband, Albert.2

Iraida and her daughter Elizabeth, nicknamed Boba. Photos from the Cengiz Kahraman Collection.

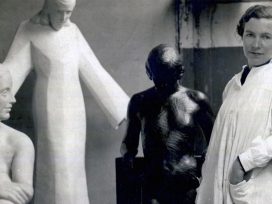

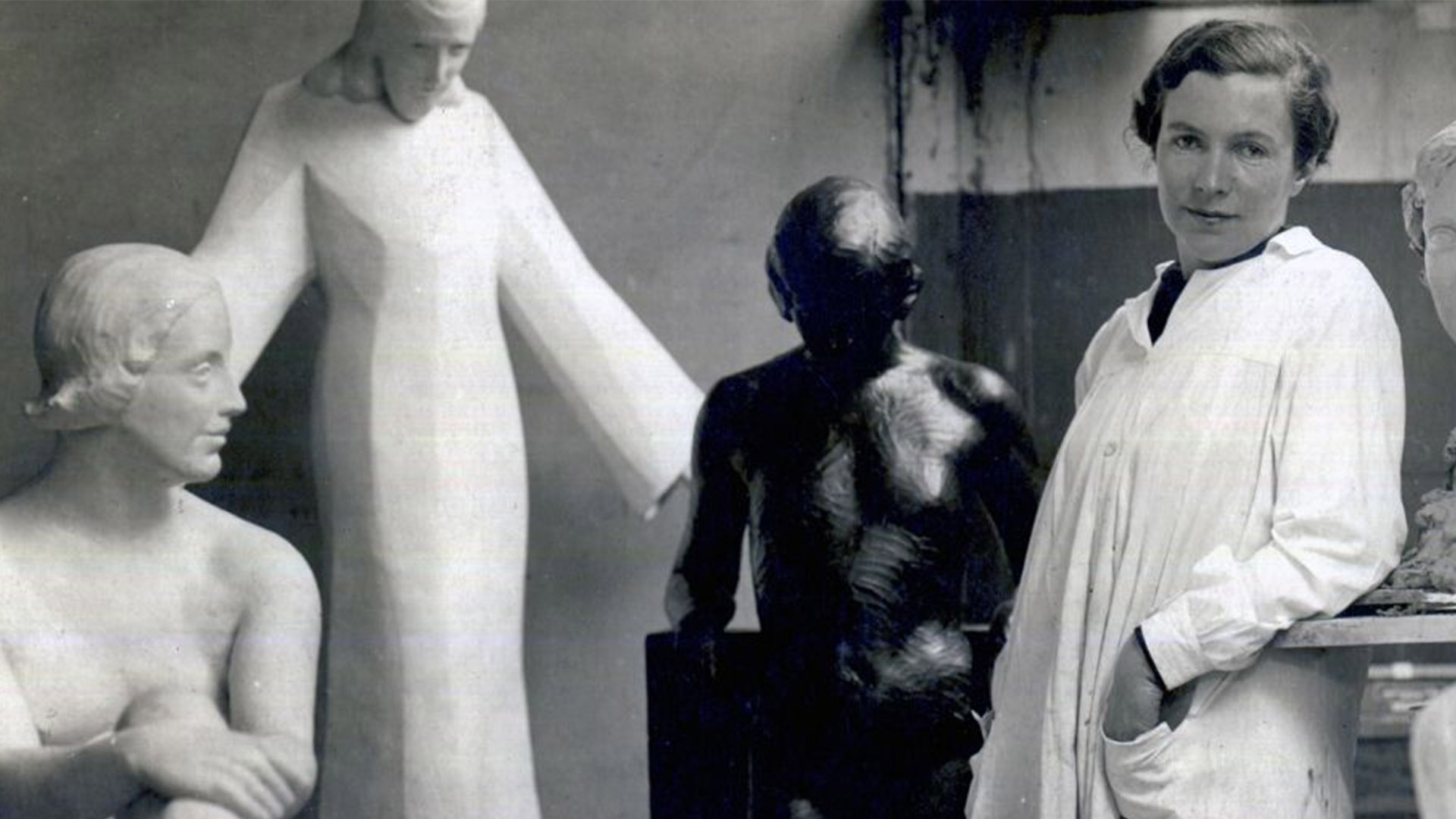

Iraida devoted all her time to Boba’s special needs and home education. Yet, she also went back to pursue her interest in arts, especially sculpture. She became a student at the Istanbul Academy of Fine Arts in 1925 and worked in Ihsan bey’s studio until 1931. In his book on Turkish sculptors (Türk Heykeltraşları), Nurullah Berk maintained that he did not hesitate to include Iraida Barry’s work among those of the Turkish sculptors.

Iraida Barry visited Paris in the early 1930s. She not only wanted to consult medical doctors about Boba’s condition, but also pursued her own interest in arts. She acknowledged the French sculptors Antoin Bourdelle, Charles Despiau, and Marcel Gimond for encouraging and influencing her works. In Paris, she took part in an exhibit at the Salon d’Automne in 1930 as well as the Salon des Independentes in 1932, 1933, and 1936. In the section about her art in Nurullah Berk’s book, Iraida claimed that it was hard for her to evaluate her own artistic works. They seemed neither beautiful nor modern to her. She underlined her interest in the process of making art rather than the end result when she said: ‘I work with enthusiasm and joy. But my works no longer exist for me after I complete them’ (my translation from Turkish).

Soulmates: Iraida and Darcy

Marcel Carga was a friend of Albert who introduced Iraida to him. Marcel was a Catholic Armenian who worked as a translator during the years of the Turkish War of Independence when he suffered an injury of his leg and an ailment of the lungs. He then began to work in a bank. Noticing Marcel’s fragile health, Albert asked him to work in his office as his dental assistant. Marcel worked with Albert until his death in 1955.

When Iraida was in Paris, she and Marcel corresponded regularly. Marcel addressed Iraida as ‘Dearest Troytchka’, ‘Troych-Q’, ‘Chère cherie’, ‘Ma chere Troytchka’, and ‘Queenie’. They exchanged many long, detailed letters. Marcel always signed them as ‘Darcy’, a nickname he acquired due to Iraida’s daughter Elizabeth’s enunciation of Marcel in the language of a toddler. These letters were written either in English or French with occasional mixing of the two languages. They portray an invaluable friendship between them. Darcy was almost like a bridge between Albert and Iraida. He constantly informed Iraida about Albert’s health, daily activities and even feelings. He told Iraida how jubilant Albert felt after receiving her letter and how the two men joyfully celebrated the good news in her letter. Darcy referred to Iraida as his compass, la boussole. He was overwhelmed with her dignity and strength. In addition to sharing his feelings with her, Darcy’s letters were filled with news about their common friends in Istanbul.

Iraida, Albert and Marcel, photo from the Cengiz Kahraman Collection

In a letter dated October 26, 1926, he wrote about meeting Doris Allen, wife of the American Consul General in Constantinople, Charles Allen who was a friend of Albert Barry. Darcy described Doris as ‘true’ and ‘not at all conventional.’ He wrote:

‘People may call her blunt. I call her sincere… She has personality too but I do not feel in her presence as with you… With her I feel like talking, with you I’d rather remain silent as if words were superfluous. I am doing a bit of thinking for myself now and then, as you see. Don’t make fun of me please. I am trying to tell you what I feel. And it is so complicated. I’d rather kiss your hand.’

In another letter dated October 29, 1926, he wrote:

‘Katevanna had dinner with us yesterday. Niania gave us a very good menu. Roasted turkey, with fryed (sic) potatoes and mashed carrots, cauliflower saute, and tomatoes farcies. Dessert, coffee. We had some vodka and Cieminski gave us a timbleful of his nalifka. We played roulette until nearly 11 o’clock. – Roulette is the fashion now, especially with Cieminski. – I saw Mrs Couteaux home at 11 … I got a letter from Helen the other day … Tell her [Helen] we’re having a Rudolf Valentino week all round: Opera, Melek, Magic. The latest is “Hacienda Rouge.” Lyda saw it. She didn’t like it. I must tell Mother to go … Ismailovitch had an exhibition at Rob. Coll [Robert College] on the 28th and 29th. He asked us to go, but unfortunately we were too busy.’

It is highly likely that the Ismailovich that Marcel Carga mentions in his letter was Dmitry Vasilyevich Izmailovich who studied art in Kiev and emigrated to Constantinople in 1919. He emigrated to Brazil in 1927 where he lived and practiced art until 1976. He was known as a portrait painter. Interestingly, The New York Times3 reporter Elmer Davis mentions the early yet unsuccessful efforts to send the Russian refugees in Constantinople to Brazil ‘where enormous tracts of undeveloped land were waiting for cultivators.’

Darcy feared losing his mental support during Iraida’s absence. As he put it in a letter dated November 27, 1926:

‘…the fact of your being away, or rather of my being left to fall back on my own resources has tested me morally in a very satisfactory way. I had, you see, to take stock of myself and I had nobody to lean on. I can’t honestly say I often thought my own thoughts for the past 3 years. I was unconsciously influenced by your mind, the same as when you held some one’s (sic) hand to help him in his first attempts to writing. You have withdrawn your hand now, and I am looking at my own handwriting. It is uneven very uneven and colorless … Aren’t you just a friend, an advisor, an older sister to me, wise and comprehending and to whom I can confide? I only hope you will not misunderstand me through a faulty expression of my thought. Even then I count on your indulgence.’

Iraida had given Darcy the book manuscript that she had written, titled Anneau D’argent (Silver Ring). Darcy was grateful that she trusted him enough to let him read her manuscript. He wrote that he had found guidance and consolation in between the lines of her book manuscript during her absence.

Within the endless pages of such letters from Darcy to Iraida, one certainly gets struck by his devotion to Iraida. There’s no doubt they confided in each other. In the absence of a close relationship with Albert, Darcy had become Iraida’s soulmate. Yet, he continued to wish well for their marriage. One particular letter (no date) ends with the note: ‘Good night Troychka, the day has been good. May God protect you, Alberttick (Albert), and Poupoutchik (Boba)’.4 Darcy’s letter dated October 29, 1926 contained greetings not just from himself but from the entire family in Istanbul: ‘Our best regards to the Mouravieff family [Iraida’s mother and step father, living in Paris]. Kiss ‘kriepka kriepka’ Poupoutchik for us.’ In response to Iraida’s referral to him as ‘Chevalier’ in one of her letters, Darcy felt extremely proud and honoured. He wrote back to her saying that he was going to live to deserve that appellation. His letters ended with expressions such as ‘Kisses, thousands of them,’ ‘God bless you Queenie,’ and ‘Je t’aime (I love you).’

It must have been an overwhelming time for Iraida when Darcy got fatally ill in November 1955. In her efforts to save her beloved Darcy Chevalier, she wrote a letter to a doctor in Zurich named Rudolf Nisser on December 2, 1955 which was returned to her with the expression ‘sconosciuto’ (unknown) on the envelope. She received a reply from a clinic in Basel to another letter that she wrote on November 26, 1955. The doctor in that clinic wrote that Mr Carga probably had pneumothroax ‘due to ruptured emphysemateous pulmonary tissue.’ The doctor suggested that it would deteriorate if left untreated whereas it could be cured with a small operation. Unfortunately, it was too late.

Marcel Carga, Iraida’s dearest friend ‘Darcy Chevalier’, died on December 7, 1955. His funeral was held at the chapel of the Feriköy Catholic Cemetery. On his obituary that appeared in Le Journal D’Orient, it was indicated that he was ‘Assistant du Dr A. Barry.’

Undoubtedly, he was first and foremost Darcy Chevalier for Iraida, her confidant and soulmate. Darcy was gone but his words as expressed in those letters were still with her. She must have kept them as a treasure before handing them over to the Columbia University archives.

Mısır apartmanı in Istanbul was the setting for the invaluable companionship between Iraida and Darcy. Iraida, a proud and self-contained woman, found shelter in that friendship after being torn from her life in the Russian Empire. They enjoyed Istanbul together, taking strolls by the Bosphorus, holding Boba’s hand while smiling to the camera. Ironically, it was Albert’s eye behind the camera that immortalized the bond between their souls.

Iraida, Boba and Marcel, photo from the Cengiz Kahraman Collection

The end of an era

Marcel Carga’s death coincided with the end of an era in Istanbul. December 1955 brought about tragedy in the heartbeat city. Three months before Darcy died, non-Muslims and their properties were vandalized viciously in Istanbul on 6-7 September, 1955. Fearing for their safety and their belongings, many left Istanbul in the aftermath of these events.

Policies geared towards the systematic exclusion of non-Muslims and the assimilation of Muslims such as the Kurds accompanied the formation of the Turkish nation-state based on a single religion (Sunni Islam) and language (Turkish). The First World War had accelerated the discriminatory policies towards non-Muslims, culminating in the Armenian Genocide in 1915, the most tragic moment in Ottoman-Turkish history. The exchange of populations between the Anatolian Greeks and the Muslims in Greece became official policy with the Lausanne Accords in 1923, leading to the further erosion of non-Muslim ways of life. The ‘Citizens Speak Turkish’ campaigns outlawed the use of languages other than Turkish in public places such as movie theatres, restaurants, and hotels, and were adopted during the single party years of the early Turkish Republic.

In a meticulous article on policies of Turkification during the early republican era, Ayhan Aktar portrays how by 1926 state employment policies prompted the exclusion of non-Muslims. The general manager of the Istanbul Telephone Company founded from British capital, for instance, complained to the company’s London representative that he had to fire his long-time chauffeur Nicos (probably a local Greek) mainly because he was non-Muslim and hence could not get a work permit. He maintained that: ‘They are driving out all non-Muslims from being waiters, including dozens of Russian refugee girls who, at present, are earning an honest living.’

Aktar also mentions a questionnaire sent by the Statistics Department of the Turkish Ministry of Commerce to the representatives of all insurance companies that contained detailed questions about their employees; asking whether they were ‘Muslim Turk,’ ‘non-Muslim Turk,’ or ‘Foreigner.’ The British Ambassador in Istanbul took note of this document and mentioned it in his report to London on March 3, 1926 in which he said: ‘the document is interesting as a proof of the distinction drawn by the Turkish Government between Moslem and non-Moslem Turkish subjects: a distinction which the Government has always maintained does not exist.’

By June 1934, there was an explosion of anti-Semitic events in Thrace, prompted by racially motivated Turkist ideas. In 1942-43, non-Muslims were burdened with a new levy called the Wealth Tax which was geared towards breaking their backs economically. Those who were unable to pay the liabilities were forced to work in the labour camp in Aşkale.

The September 6-7, 1955 events, then, represented another critical moment in the systematic erosion of Istanbul’s non-Muslim population. By 1964, another exodus of the Greeks from Turkey took place, as residence permits of Greeks who were married to Greek-Turkish citizens were abolished. It was through these critical turning points that Istanbul lost its very essence: diversity.

Iraida Barry photo in Cengiz Kahraman Collection

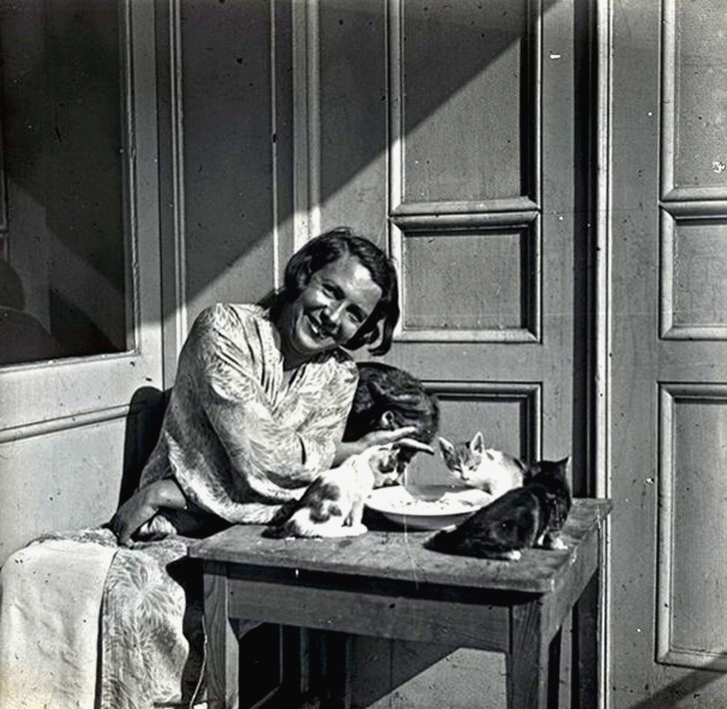

Iraida Barry lived through such hostility towards non-Muslims from the moment of her arrival in Istanbul in 1919. Her anxious presence in Istanbul was akin to a ‘message in a bottle’, floating in uncharted waters. She had an inner world that she kept for herself. She remained guarded and aloof from a society that increasingly discriminated against non-Muslims. Her messages which metaphorically remained in a bottle in Istanbul finally reached shore to be disclosed at the archives at Columbia University. It seemed like she adored and enjoyed Istanbul without interacting much with the Muslim locals. Although she lived in Istanbul from 1919 until her death in 1980, her life remained transient and fragile. As she got older, the people she interacted with on a daily basis, such as the street grocer and her neighbours in Istanbul must have called her ‘Madam’, a common expression used for non-Muslim women that paradoxically combines respect for the elderly and exclusion; an appellation that indicates a lack of belonging. Iraida is buried along with her mother and daughter at the Orthodox Christian cemetery in Şişli, Istanbul. All three were women of Istanbul who led lives gripped with a fear of evanescence. Since Iraida was no longer here to set the record straight, their story had to be told by other women. Gül Dirican was the first who felt this responsibility towards Iraida in the late 1990s when she encountered her photographs in the Cengiz Kahraman archives.

The city and its people

At the end of 1920, a few weeks after Iraida and Albert’s wedding, a steamship was making its way towards Constantinople. On the deck was Eugenia S. Bumgardner, a Red Cross relief worker from Staunton, Virginia, and the author of one of the earliest books on Istanbul’s Russian refugees titled Undaunted Exiles. As the ship approached the shores of Istanbul, Eugenia decided to go up to the deck of the ship since she ‘did not wish to miss one single moment of that fabled entrance to Constantinople.’ As they were transferred to small boats (kayık) and headed towards the Galata bridge, she described how she fell in love with Istanbul:

‘Stamboul, at this hour of dawn, resembled the illusory cities one sees at sunset, when great billows of clouds race across the sky, touched by a thousand fleeting colors, pastel shades of matchless beauty … The sea was running high and as the enormous waves rolled towards us, I marvelled at the skill of our boatman as he turned his little raft and rode them. However, each time that we went down into the great green trough, it seemed to me that death were a small price to pay for having seen Stamboul awaken, cast aside her veil, and reveal her perfect beauty.’

As I read her lines, I could easily imagine the panorama facing her and how breathtaking Istanbul could be. I had often seen its splendid sights myself on boats between Karaköy and Kadıköy, albeit at a different time, in the aftermath of the careless construction of thousands of shoddy buildings heaped on top of one another. Nevertheless, Istanbul is first and foremost a resilient city. Despite all the atrocities inflicted on her, she still upholds that fabled entrance that left Eugenia Bumgardner spellbound back in December 1920.

Eugenia Bumgardner worked closely with the Russian refugees in Constantinople. She was particularly interested in the well-being of Russian women. In a piece she penned for The New York Times (July 9, 1922), she described the Russian dame de service who had become the main point of attraction in Constantinople’s new Russian restaurants. While some Russian women were working as musicians, the dame de service were obliged to greet clients and serve them food. They were tipped to spend time with wealthy clients and were fired if they did not oblige. Bumgardner described them as women who had the chic of a Parisienne coupled with the education of a nobility. She was especially taken by their dignity:

‘Although for two years they have lived in an atmosphere of intrigue and of calculation; although they have been bartered for and certainly traded in, they hold their head high. They look you squarely in the eye: there is nothing either brazen or cringing in their bearing.’

Bumgardner observed the Russian men in Constantinople as well. They were mostly former soldiers of the Tsar’s army. Some of these noble Russian ex-officers played music in restaurants while watching their wives work as dame de service. Soon, some of these men grew violent toward their wives. The doorman at Albert Barry’s dental office was also a former decorated officer in the Tsar’s army. Bumgardner describes5 how some of these former Cossack officers were now riding horses in order to amuse viewers in Constantinople:

‘Despite their untrained horses, these men rode superbly, cutting branches from limbs with their sabres, cutting apples in two, picking up objects from the ground, vaulting off and on their horses, turning somersaults, riding standing, riding on their heads, their bodies straight in the air, all with the horses going at full speed. Then, as their comrades stood around them, clapping time with their hands, they danced the “lezguinka.”’

Russian refugees lived in tragic conditions. Anne Mitchell, the executive secretary for Admiral Bristol, the American High Commissioner in Constantinople, gave the following account about the living conditions of the Russian refugees in a piece in The New York Times:6

‘Miss B. [this must be Eugenia S. Bumgardner], working with our local Red Cross came to take me out, first to what she called a hospital or invalids’ home… indeed I had never seen its like. It was an enormous loft its obviously leaky roof supported in some rather inapparent way by a light framework, and the big space, as far as one’s eye could reach filled with what seemed a formless mass of suspended rugs and hangings … two or three beds were the only furniture, and I believe not all of them have beds. There was no heating and the best they had for cooking was a primus lamp. All the families in this building have at least some of their members in poor health, 60 per cent below normal; and many tubercular, Miss B. said.’

Iraida Barry’s marriage to Albert rescued her from such a fate. But she was still a refugee. She led a life with immense intensity in her own internal world coupled with anxieties and feelings of exclusion. She spent her years in Istanbul engulfed in an effort to preserve the memories of her life in Sevastopol. Her story was interlaced with the story of Istanbul for she, like Istanbul, preserved her dignified stance irrespective of the tragedies that she faced.

Almost all eyewitnesses underscored the dignified and graceful ways of Istanbul’s Russian refugees. This was partly due to the aristocratic upbringing of many of these refugees. They, like Iraida, could speak multiple languages, were avid readers and had refined tastes in music and gastronomy. Such attributes seemed to have contributed to their resilience. In an essay that appeared in The Atlantic Monthly in March 1922, Vera Tolstoy, one of the grandchildren of Lev Tolstoy and herself a refugee, explained the sources of their strength.

She maintained that most people think to be rich and then to lose one’s entire fortune was worse than being poor all along. On the contrary, Vera Tolstoy argued that the former rich had hope, ‘the hope born of knowledge of better things; the hope belonging to experience, to retrospection: the hope that lies in ourselves, not in indefinite surmises and expectations.’ She maintained that, although one felt the material deprivations, the hunger and cold, the hard make-shift bedding, one would feel like a ‘phantom dreamer passing through a dream’ hoping to be awake and be well: ‘When, at last, the awakening comes, fitfully, gradually, an inner process has been accomplished in us – we have gained our equipoise, we can stand erect.’

Iraida Barry, photo in Cengiz Kahraman Collection

To love a city but not its citizens

In conveying parts of Iraida Barry’s life, I tried to circumvent the trap of an Orientalist discourse that leads to a glorification of her story over the life of the local, Muslim Turks and/or the Armenians and Greeks of Istanbul. My main endeavour was to tell the story of a proud woman whose papers I came across in the archives. Moreover, the background to her story depicted a critical era in the history of Istanbul. Some of the eyewitness accounts used in this essay, however, openly favoured the Russian refugees over the residents of Istanbul and even resorted to discriminatory language. The picture would have been incomplete without mentioning them.

Eugene Bumgardner’s description of the physical attributes of Russian women, for instance, were in stark contrast with their Turkish counterparts.7 Russian women were described as: ‘big, handsome blonds,’ with ‘wonderful hair, lovely clear skins, small well-shaped noses, bright eyes, pretty mouths, good teeth.’ Bumgardner also made note of their small hands and feet, slender ankles, arched insteps, musical voices, as well as quiet and graceful movements; that they smiled more than they laughed. Bumgardner’s observations of the Turkish women, on the other hand, were laden with discriminatory remarks. She referred to them as ‘dull and uninteresting.’ She also described their ankles as thick, and their feet as big and ugly. She also wrote that ‘they walked badly.’ If and when one occasionally saw a ‘lovely face with large, lustrous eyes and beautiful skin,’ Bumgardner was sure that there existed a ‘strain of Circassian blood.’8

Photo from Cengiz Kahraman Collection

Bumgardner’s distasteful observations encompassed not only the Turks but all local residents of Constantinople. In describing the vivid life created by the mushrooming Russian restaurants in Pera, she did not hesitate to mention that they replaced the ‘dull, drab, and unattractive’ ones owned by Greeks and Armenians in which ‘the food was bad and expensive: no one ate in them unless compelled to do so.’ Bumgardner’s adoration of the Russian refugees blinded her to other lives in Istanbul.

Such observations about the locals by eyewitnesses of Istanbul’s Russian years were in stark contrast with their admiration for the sights of the city. Istanbul was under occupation by the British, French, and Italian forces between November 1918 and October 1923. Bumgardner’s views were most likely shared by the occupying forces. Bumgardner’s depiction of Constantinople’s breathtaking sights from the deck of her steamer were incompatible with her representations of the city’s natives. She adored the city and its Russian refugees while garnering a hostility towards the locals, both Muslim and non-Muslim.

To love a city but not its citizens… This was indeed an awkward combination. After all, what is a city without its people? When seen from a ship entering the Sea of Marmara from the Bosphorus, Istanbul looks like, in the words of Orhan Pamuk ‘millions of hungry windows opened to peek at that ship and the Bosphorus while obstructing each other’s views and mercilessly hindering one another.’ (my translation from Turkish). The people behind those windows are part of the city’s fabric. The gazes of those behind the windows inevitably meet the eyes of those on the deck of the ship approaching the shores of the city.

A city of refugees

Istanbul has always been a city of refugees. Today, its most visible refugees are from Syria. Turkey hosts about 3,6 million registered refugees from Syria. Thousands of refugees live in camps in the southeast of Turkey. There are about 550,000 Syrian refugees registered in Istanbul. It is estimated that another 300,00 who are registered in other cities also live in Istanbul.

Today, it is not uncommon to observe similar expressions of adoration for the city coupled with a distaste for Syrian refugees among the Turkish citizens. Istanbul’s Syrian refugees often become targets of discrimination and hostility. Ironically, a discourse of discrimination towards the Syrian refugees seems to coexist with a nostalgia for Istanbul’s Russian years, especially among the Turkish elite. How can one explain the coexistence of nostalgia for Istanbul’s Russian refugees and despise for its Syrian refugees – almost a century apart?

It is important to underline that refugees face discrimination irrespective of their origin. Both the Russian and Syrian refugees of Istanbul were pushed to the margins of the society and forced to take up demeaning jobs, albeit Western governments awaited Russian refugees with assistance and open doors. The Russian refugees enhanced the soon-to-fade non-Muslim culture of Istanbul in the 1920s and fostered the city’s heterogeneous features.

The nostalgia for Istanbul’s Russian years didn’t have to be expressed in discriminatory language, referencing the unparalleled beauty of Russian women, coupled with distaste towards the locals. The real beauty is indeed in heterogeneity. And the devil is hidden in the layers of expressions. That is why words are too important to utter carelessly.

Discriminatory expressions are just that: discriminatory. It is then highly important to specify a non-discriminatory reason in longing for Istanbul’s Russian years, a reason other than the slender ankles and clear skin of Russian women. The nostalgia for Istanbul’s Russian moment is actually a yearning for diversity, a longing for many religions and languages living together albeit the ever-existing hierarchies and inequalities among them. Diversity gives a city its colour. A city becomes ‘dull, drab, and unattractive’ (to borrow the expression Bumgardner used for Pera’s Greek and Armenian restaurants) when it loses that colour.

Istanbul’s resilience is not just in physical beauty but also its ever-emerging diversity. It is this heterogeneity that turns Istanbul into a heartbeat city. Mısır apartmanı that once sheltered Iraida and her refugee friends is still a venue for the expression of diversity. Today, one can observe Syrian teenagers singing songs in Arabic while timidly holding hands with the members of their makeshift musical bands in front of this landmark building. They face the ordeals of refugees who were forced to flee their war-torn cities.

Edward Said referred to New York City as the ‘exilic city par excellence.’ Perhaps, it is time to underline that Istanbul leaves one spellbound because of its similarly exilic nature. Diversity and the multiple colours of its people are the sources of Istanbul’s heartbeat. We owe it to its unwavering resilience to express our adoration for her in a language that doesn’t discriminate.

*

I am grateful to Marlow Davis who is conducting doctoral research into life and literary works of Iraida Barry at the Slavic Languages and Literatures at Columbia University for reading the manuscript and generously sharing his knowledge with me. Equipped with command over the Russian language, he is studying to bring together the pieces of the story in the Iraida Barry Papers. This essay is only the tip of the iceberg of the vast papers at the archives. I also thank my friend/colleague Ayhan Aktar for kindly reading the manuscript and sharing his thoughts. Needless to mention, the sole responsibility for the contents of this essay belongs to me.

Iraida Viacheslavovna Barry Papers, 1820s-1970s, Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and Eastern European History and Culture, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries (Bib ID: 4078297)

Albert Barry died on December 28, 1962 due to complications in a minor surgery at Istanbul’s Italian hospital.

The New York Times, December 4, 1921

‘Bonne nuit, Troychka, la journée a été bonne. Que Dieu vous garde, toi, Alberttick, et Popoutchik’

The New York Times, June 25, 1922.

The New York Times, April 23, 1922

The New York Times, July 9, 1922.

The New York Times, June 25, 1922.

Published in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Voicing opinions to explain political tensions from afar is contentious for those treated as mute subjects. Focusing solely on distant, global decision-making disguises local complexity. Acknowledging the perspectives of East Europeans on Russian aggression and NATO membership helps liberate the oppressed and open up the debate.

Georgia’s ‘March for Europe’ protests express deep polarization in the country over the current government’s pro-Russian course. The return of Moscow-friendly oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili to official politics signalled the beginning of an election campaign whose outcome will decide Georgia’s democratic future.