Check, control, cancel or care

Where can we turn if our social networks, structures and governance can’t be trusted? Cancel culture, disinformation and the lack of boundaries define our perception. Geert Lovink, Eliot Higgins and Matilda Amundsen Bergström provide some welcome thoughts on solidarity overcoming abuses of power.

Surely I wasn’t the only one feeling insecure? The coach journey from Slovenia to Italy was on a busy route. And we were all in the same vulnerable position – nobody had been given their IDs back yet. The driver, who was behind schedule, had already pulled back onto the motorway, the border rapidly diminishing in his rearview mirror. I fidgeted in my seat, looking furtively at others. What if someone’s ID had been accidentally left behind? Sitting towards the rear of the coach, I would be one of the last to receive their passes from the steward. But, from there, I could clearly see, when everyone had their rightful documents, that he still had his hands full. Somehow, he had one passport too many.

I felt for the steward whose responsibility had just augmented beyond his basic wage. And, with my own worn UK passport, soon to be devalued in the EU, safely in hand, I felt for the mystery person whose ‘identity’ had disappeared and was now travelling at speed towards Trieste. But what can you do in a captive situation? Nobody else seemed perturbed. The majority were absorbed in their phones. What else but join them and distract myself by telling an ‘amusing’ story?

Minimum Monument art installation by Nele Azevedo. Photo by Aidan McMichael from Flickr.

Users trapped in virtual cages, clueless of how to escape

We already know that social media is an identity crisis minefield. And Geert Lovink’s recent article on cancel culture recognizes the trap that accompanies fickle changes in online public opinion. Every fascination is ‘in’ one minute and ‘out’ the next, only to sometimes come back into favour again. And the range of what and who can be targeted is staggering – Lovink cites the Dalai Lama, Israel and novelty internet rappers as victims of cancel culture, all in rapid succession.

Cancel culture’s paradox, in Lovink’s opinion, is the disjuncture between ‘the old media model’ where the audience ‘outsourced their desires’ to misbehaving celebrity, who ‘both fascinated and disgusted ordinary folk’, and the newer position where ‘we’re all influencers now’. He points to the frustration that arises when well-worn narratives win out over the user’s desire to remove them once and for all.

Lovink’s call to ‘delete your profile, not people’ advocates ‘fighting against abstract violence (code, borders and other forms of structural separation)’ instead, saying: ‘It is our duty as activists and researchers to make power visible.’

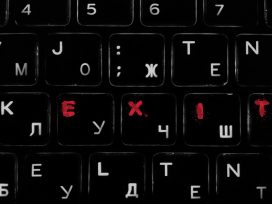

Those who control the narrative and those who keep them in check

Bellingcat founder Eliot Higgins also knows a lot about deleting social media profiles – albeit in a very different context. ‘If we’ve found some Russian officer and he’s got a social media profile, then as soon as we make it public it’s going to be deleted very quickly’, he says in the new episode of Gagarin, the Eurozine podcast, ‘So we’ve been showing that stuff to the joint investigation team and giving them a reasonable amount of time to preserve it.’

Higgins discusses how Bellingcat’s pathbreaking investigations of the shooting down of the MH17 flight and Assad’s use of chemical weapons in Syria have been corroborated by the ongoing Joint Investigation Team trial in Amsterdam and the recent report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.

Bellingcat’s effective trawling of online information gives Higgins valuable insight: ‘You can’t really have a sensible discussion about things like Russian disinformation if you don’t understand that not everyone actually thinks they’re sharing disinformation. They think they’re sharing the truth.’ Although he recognizes that there’s ‘clearly an attempt to control the narrative’, he also warns against disinforming about disinformation: ‘That is one thing I often see with journalists, think-tanks and all kinds of organizations working on disinformation … they then start making conclusions based on their own bubble.’

‘… the choice to not use power’

In his recent Glänta editorial, Göran Dahlberg asks whether ‘old tools can find new uses and new tools can awaken old and forgotten knowledge’ from within or outside the system. The journal’s resultant ‘toolbox’ is a collection of conceptual proposals for how to understand contemporary social structures.

Matilda Amundsen Bergström’s article reclaims temperance as a contemporary virtue. The sixth century ethical cornerstone – long valued alongside prudence, courage and justice, yet dismissed as ‘naïve, if not downright silly’ in postmodern times – is seen as a means to redefine limits in a seemingly boundless world. ‘At its core, temperance means finding, respecting and defending boundaries – especially one’s own.’

Bergström recognizes that our boundaries are out of kilter. Some, she considers, are being eroded by free-flowing ‘capital and information’ or moral dilemmas about ‘love, identities and life itself’. Others, meanwhile, are being reinforced by physical ‘barbed wire fences and brick walls’ or ‘acts of solidarity to protect other people and worlds.’ Between these extremes, it’s no wonder that the self might also be confused between choosing freedom and restraint. Bergström is therefore careful to distinguish temperance from self-denial and abstinence, whether refraining from environmental excesses such as eating meat and flying or bodily indulgences connected to alcohol, food and sex. Rather, she presents it as ‘the choice to not use power’, valuing ‘dispensation’ and ‘being with others’.

In keeping with Lovink and Higgins, and in Bergström’s stand against manipulations, is first and foremost a mark of solidarity. Still on the ride to Trieste, I draw the consequence: if I ever witness a misplaced possession of such value again, I will know to get off my phone, not assume I know what has happened, and act in solidarity too.

And this newly strengthened solidarity has much larger targets too.

What happens in Belarus

Events in Belarus since 9 August have overtaken all expectations; and yet this is only the beginning. Despite the democratic opposition’s incredible success in mobilizing a full-blown national uprising, the Lukashenka regime has not collapsed quite yet. What lies in store for the people of Belarus in the coming days and weeks depends on whether the movement remains strong – and how far the regime is willing to go to preserve the status quo. And, of course, how Russia decides to act.

Our partner Osteuropa has been quick to respond with an ongoing series of penetrating interviews (in German). Two of them – with German Belarus expert Astrid Sahm and Belarusian writer Artur Klinaŭ – are so far available in English in Eurozine, and more will follow. Our partners at the Institute for Human Sciences are also publishing an excellent Belarus blog, which is definitely worth checking out.

This editorial is part of our 15/2020 newsletter. Subscribe to get the weekly updates about our latest publications and reviews of our partner journals.

Published 19 August 2020

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Vienna’s hosting of Ukrainian artists and writers recalls the days of the fin de siècle, when the city was a magnet for intellectuals seeking freedom from Tsarism. But despite strong historical affinities, subtle barriers to solidarity with the Ukrainian exiles remain.

Prisoners of conscience

A conversation with Myroslav Marynovych

Defenders of human rights often face high stakes. When the Ukrainian Helsinki Group openly challenged the Soviet Union in the name of the 1975 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, young dissidents soon became political prisoners. The price for being a non-conformist was steep yet encouraged solidarity, paving the way to Euromaidan.