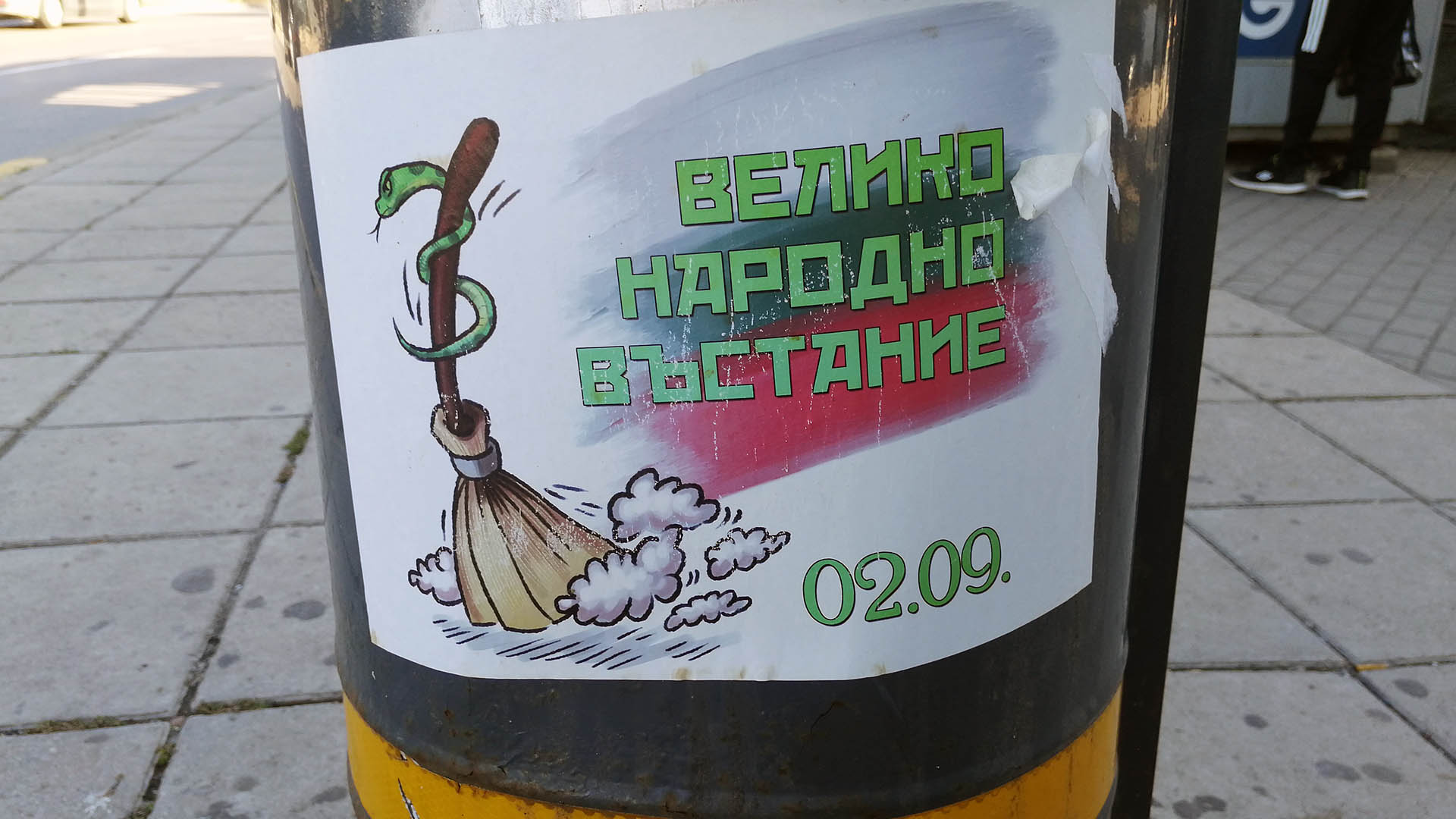

Bulgaria’s revolt against the past

Sparked by raids on the offices of the Bulgarian president Rumen Radev in July, after mounting dissatisfaction with the Borisov government, the ongoing protests in the country express broad resentment towards a powerful clique whose corrupt methods hark back to the criminal 1990s.

Around the fiftieth day of anti-corruption protests in Bulgaria, a friend of mine told me: ‘I went to the square to talk with these young people. I realized what they are after. They’ve studied and worked in Europe, and they say that everything there is neat, clear and easy. They come back here and see that the thugs in government have created chaos. These young people simply want here to be like there, because they know it’s possible.’

My friend had hit upon the essence of the revolt. Over the last decade, Bulgarian society has adopted the mindset of the twenty-first century but continues to be governed by people stuck in the 1990s – the age of the mobster. Today, Bulgarians want to get rid of these people and become, as Bulgaria’s first democratic prime minister, Filip Dimitrov, used to say: ‘a normal western country’.

The next day I saw headlines on European websites reading: ‘Opposition party leader arrested at peaceful protest.’ I thought the reports were about Russia, Belarus, or the likes. But then I looked at the photo. The distressed face I saw in the stranglehold of a large police officer belonged to my friend and associate, Borislav Sandov, a co-chair of the Green Movement.

The European Greens called for Sandov’s immediate release. We are used to seeing such calls in response to events in Russia and Belarus, but not in EU member states. Having put the country back to the 1990s, the people who have captured Bulgaria are now lowering standards of democracy and rule of law to those of post-Soviet autocracies.

Politics is a conversation about our common future. In Bulgaria, the future is rebelling against the past. For the first time in two decades, the liberal urban middle class is backed (rather than mocked) by all other social strata and age groups. The protest is not partisan. It has rallied left and right, liberals, Greens and all sorts of others.

Supported by up to 65 percent of the country’s population, according to opinion polls, the protest is also the most popular in Bulgarian history. Unlike on previous occasions, ordinary people have taken to the streets not because of hunger or the prospect of it. The country’s economic environment is comparatively stable and even the COVID recession is (for the time being) moderate. Rather, people are protesting because their dignity has been injured. This is not about a more affluent future, but about being able to live without being insulted or bullied. It is a protest driven by ideas, not material interests.

The power-holders, the people of the ’90s, repeated the crucial mistake of all autocrats who delude themselves that they will be in power forever: succumbing to hubris, which inevitably leads to contempt. As the MP of the parliamentary majority recently said, ‘We’ve had enough of these protests. It’s high time the shepherd grabbed the crook and drove the flock back into the pen.’

The people, however, are not a flock. They are the sovereign and nobody’s property.

Photo by Oleg Morgan / CC BY-SA from Wikimedia Commons

How did we end up here?

Boyko Borisov’s government had already lost popular support before the COVID crisis hit. The constant dismissals of dissenters, the takeovers of private businesses, the persecution of journalists, the threats, the flagrant misappropriation of public funds and public resources – over the years, all of this had affected every family in Bulgaria. By some point in mid-2019, Borisov had lost his electoral base. Ordinary people in small towns and villages no longer identified with him as ‘one of us’. Instead, they had come to regard him as the local bully. This shift in the public mood went unnoticed both by pollsters and by Borisov’s own party. All that was visible on the surface was a gradual decline in overall support.

After COVID struck in March, the government duly declared a state of emergency. Public approval for the powers that be suddenly rose, like in most European countries at that time. There was talk of ‘a new credit of trust’. However, the mobsters played a nasty trick on the population. Instead of appreciating this sudden support and doing their best to increase it, they began muttering about remaining in office for another twenty or thirty years.

What do people do when they assume they will be in power forever? They begin to behave outrageously. They lose all self-restraint. They come to perceive the country and the people as fair game.

Throughout the spring of 2020, Bulgaria’s ruling elite violated the social contract and the laws of the land. One scandal followed another, day after day, all of them involving misappropriation of public resources. Predatory plundering took place in protected areas along the Black Sea, where government cronies destroyed sand dunes, laid concrete foundations and erected hotels. All of this was in brazen violation of conservation laws, but government institutions kept reassuring the public that everything was legit. In one case, they even referred to the construction of a huge hotel as building a ‘landslide control project’.

Meanwhile, every other day the new chief prosecutor announced lists of ‘enemies’ that the state would be going after. All were public figures critical of the government, publishers of independent media, or entrepreneurs who had refused to sign over their businesses.

Every civic reaction was dismissed with haughty disdain or deliberate arrogance. The citizens were called ‘blockheads’, ‘anarcho-liberals’, ‘idlers’, ‘nasties’ and ‘paid saboteurs’. A dozen investigative journalists and presenters were abruptly sacked from the national TV stations. The deputy prime minister explained that the citizens didn’t trust the institutions because they didn’t understand how they functioned and knew nothing about ‘the workings of democracy’. Borisov himself claimed that only smugglers, drug traffickers and criminals could protest against him.

An explosion was inevitable. A national environmental protest was held on 25 June. Unlike the usual couple of thousand ‘Greens’, tens of thousands took to the streets. They demanded not only an end to the destruction of the natural environment, but also the government’s resignation. Hristo Ivanov, a former justice minister who now leads an opposition party, attempted to land a dinghy on a public beach appropriated by a prominent member of the ruling oligarchy. He was intercepted, manhandled and pushed back into the water by a group of bodyguards who turned out to be officers of the National Service for Protection, the agency that provides security to politicians.

All this was filmed and livestreamed. In just 24 hours, the video was watched by more than a million viewers out of a population of seven million. A couple of days later, heavily armed men in uniform, commanded by the chief prosecutor, raided the offices of the President of the Republic, Rumen Radev, who had repeatedly expressed support for environmental causes. The protests erupted on that same day and have been going on ever since.

A number of significant things have happened. The first is that the Bulgarian nation has finally overcome its fascination with both extreme nationalism and authoritarian government. The second is that the quasi-fascist parties ruling in coalition with Borisov’s party, GERB, no longer stand a realistic chance of crossing the four per cent hurdle to parliament. Third, the fact that the people as a whole are protesting against an authoritarian prime minister demonstrates that in Bulgaria, unlike in other eastern European countries, reliance on a ‘strongman’ has passed its peak. The protest is spearheaded by people with liberal democratic demands. In Bulgaria, at least, the tide of authoritarian populism has started to turn.

A European people are insisting on living in the twenty-first century, where things are neat, clear and easy. They are trying to get rid of a regime made up of criminal elements left over from the ’90s. Civilisation versus barbarism, order versus disorder, integrity versus the moral decay known as ‘corruption’ – that is the essence of the Bulgarian protests of 2020.

Published 5 October 2020

Original in Bulgarian

Translated by

Katerina Popova

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by IWM © Evgenii Dainov / IWM / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

After six months of protests, there are grounds for hope that the tide is turning in favour of the Serbian student movement: first, the unification of the opposition around the movement’s demand for new elections; second, the emergence of a strategic alliance between the students and the EU.

The protests over the arrest of Istanbul mayor Ekrem İmamoğlu are the biggest display of anti-government feeling in Turkey since Gezi Park. Again, people are challenging the culture of public silence; and again, they are being punished for doing so.