‘Culture & Démocratie’ editor Hélène Hiessler talks to journalist Elena Diouf about ‘bitches’, weaponizing abuse and deflecting stereotypes.

Hélène Hiessler: How did you come to be interested in hip-hop generally, and the figure of the ‘bitch’ in particular?

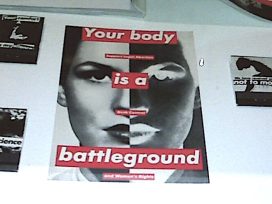

Elena Diouf: As an undergraduate I used the #MeToo movement as a starting point to investigate the media coverage of different kinds of feminism, which I analysed alongside the rollback of women’s rights. The figure of the ‘bitch’ in American rap featured as a minor part of my first dissertation, but I was interested in taking the idea further because it’s not a subject that has received much academic attention.

It was clear to me that hip-hop was a growing genre, particularly in the United States, where it has been reappropriated by African American women rappers including Nicki Minaj, who was one of the pioneers around ten years ago. That caught my attention: I wanted to dig deeper and see if the ‘bitch’ had the potential to become a contemporary feminist figure capable of subverting gender and race norms, or if she was just a marketing phenomenon.

Hélène Hiessler: The researcher Keivan Djavadzadeh , whom you cite in your work, writes that while cultural industries play a large role in the maintenance of cultural hegemony, ‘popular culture is also, simultaneously, a space for contesting hegemony’. Do you think hip-hop is characterized by this ambivalence?

Elena Diouf: I’m not sure if hip-hop is fully part of European hegemonic culture. It is clearly the genre that has had the most success in recent years, especially among teenagers and young adults but, in France for example, it is still not played much on traditional media: radio, television and so on. Rappers rarely appear as guests on shows and they are awarded few prizes, when compared to artists working in other genres.

Hip-hop is primarily broadcast through music and streaming platforms and I wouldn’t say that it has shed its subculture status. In the United States, on the other hand, it seems much more established: there, rap is dominant. I also think that modes of consumption have changed. For example, French rappers have their own marketing techniques, such as posting teasers for several days before a release so that everyone will be on their smartphones at midnight to listen to a new song. That kind of thing reaches beyond the hegemonic media.

Nicki Minaj performing in Oslo 2012. Spektrum Photo: Tom Øverlie, P3.no / NRK P3 from Flickr.

Hélène Hiessler: Who is the ‘bitch’?

Elena Diouf: I use the term ‘bitch’ to mean a woman of colour who embodies independence and power both in her lyrics and in the hip-hop persona she adopts. Her lyrics celebrate sexuality, money, the fuller figure, the beauty of Black women, and the joy of taking back control over life.

The ‘bitch’ exists within three interlocking systems of oppression: gender, class and race. This produces a very specific life experience. The ‘bitch’, as I have described her, is inextricably linked to the intersectional philosophy introduced by Black American feminism – particularly that developed by bell hooks in the 1980s, which looks back to American slavery in the seventeenth century.

Artists like Miley Cyrus or Madonna, who may resemble the ‘bitch’ in terms of their provocativeness, do not share the same lived experience. They cannot be considered ‘bitches’ in the way I use the term because they don’t apply the same codes – which isn’t to suggest that they aren’t feminists.

Hélène Hiessler: Is the ‘bitch’ tied to a particular musical genre?

Elena Diouf: The word ‘bitch’ was used in American jazz back in the 1930s but, sixty years on, it achieved notoriety as a term of abuse in the work of African American rappers like Snoop Dog or Dr Dre. The 1990s saw a turning point thanks to a duo of African American women, who named themselves BWP (Bytches With Problems). They took the insult, reversed it and replaced the ‘i’ with a ‘y’ as a way of reappropriating it. They turned it into a badge of identity.

Now, nearly thirty years later, the word appears in the lyrics of female rappers like Nicki Minaj, Cardi B and Rihanna, either as a statement of identity (referring to themselves as ‘bitch’) or as a sort of second-degree insult. This notion of reappropriating and weaponizing an insult is very important. The connection to rap, initially an overwhelmingly masculine space, is clear.

In pop, it would be different. But, as I mentioned before, the reference to the lived experience of African American women is also key: ‘bitches’ play with stereotypes specifically associated with women of colour.

Hélène Hiessler: What cultural assumptions about Black women does the ‘bitch’ want to deflect?

Elena Diouf: There are several negative stereotypes that date back to slavery. They include the Jezebel, a hypersexualized, bestial woman with loose morals; the Mama, a stay-at-home mother and housewife; and the virile and aggressive woman.

But the most interesting of these stereotypes is the Jezebel, with her highly eroticized body and lack of sexual self-control. In the era of the Atlantic slave trade, the Jezebel trope was used to portray Black women as sexually aggressive in contrast to virtuous white women. Whiteness was the accepted standard of beauty while Blackness was synonymous with ugliness. This is the stereotype that today’s ‘bitches’ are reappropriating, especially in the style and imagery of their videos, which include lots of animal print, erotically suggestive poses, costumes consisting of underwear, fishnet stockings, latex and other hints at the world of striptease or prostitution.

These references, in particular, are off-limits as far as white women are concerned. While Cardi B is often called vulgar, even pornographic, artists like Lady Gaga or Katy Perry, who can be equally provocative, are more often discussed in terms of artistry or flamboyance.

This article was first published in French by the Belgian journal Culture & Démocratie. Their 52nd issue of May 2021 deals with popular culture, from historical populisms to hyperindustrialisation to the masquerade.

Hélène Hiessler: Which feminist school of thought does the ‘bitch’ belong to, in your view?

Elena Diouf: The figure of the ‘bitch’ is associated with several long-established feminist schools of thought, but especially with debates that have raged among feminists for decades about the use and hyper-sexualization of women’s bodies. In the United States in the 1980s, these debates crystallized into fierce conflicts often referred to as the Sex Wars, which pitted two different visions of sexuality against each other. One saw sex as an act of oppression, and the other saw it as a space for potential emancipation.

The Sex Wars are exemplified in the perpetual debate around pornography and prostitution, which continue to divide feminists. But the ‘bitch’ is also associated with Black feminism and the concept of intersectionality.

Black feminism emerged in the United States around the 1960s. Although it subsequently took a range of different paths, Black feminism was the first to initiate a proper consideration of race and gender, and the ways in which they interacted. This later helped introduce the concept of intersectionality as an analytical framework in wider feminist thought.

The figure of the ‘bitch’ emerges from long-established schools of thought and philosophies that form part of what we could call ‘pop feminism’. I don’t think this can be defined in a single or precise way, but what we can say is that pop feminism is characterized by a pervasive presence in – or perhaps even dependence on – popular culture: music, film, fashion and social networks.

The fact that the ‘bitch’ exists as a feminist figure at all is precisely because it appears in so many different contexts. This is also true of many other figures in pop feminism: models, Instagrammers, and so on. It is a form of feminism that relies on and generates intense media attention.

Leikeli47 live at the Velvet Underground. Photo by Mac Downey via The Come Up Show from Flickr.

Hélène Hiessler: Some people prefer to talk about post-feminism, as if the developments you describe marked the end of ‘authentic’ feminism.

Elena Diouf: Yes, in contrast to a more ‘traditional’, but also stereotyped, version of feminism: that image of a bitter, man-hating woman with hairy legs. Pop feminism is nothing like this. It can take any number of forms including, most controversially, using one’s body to achieve one’s goals. It also encompasses whatever is ‘outside the norm’, rather than confining itself to the traditional female/male dichotomy. It leaves space for all genders and orientations, the specific experiences of every individual.

But there is still a long way to go. The lived experience of women of colour is still largely invisible within Eurocentric and bourgeois feminisms, so tensions are fully justifiable and bound to arise.

Hélène Hiessler: Critics of pop feminism accuse the ‘bitch’ of encouraging individual success rather than working for collective emancipation. Is that fair? Does this form of feminism challenge social inequalities, for example?

Elena Diouf: The ‘bitch’ is subversive, but she has her limitations. The figure conveys no suggestion of a collective movement led by women of colour. But is that her role? Above all, is that what the figure of the ‘bitch’ aims to do? I don’t think so.

Empowerment, the notion of transforming inequalities, is obviously collective as well as individual. But the collective dimension of the idea is often overlooked, even by some feminists, including ‘bitches’ themselves. I don’t know whether they challenge structural inequalities, but ‘bitches’ do help to raise awareness of inequalities in popular culture by embodying a feminism that goes against the grain of cultural hegemony.

‘Bitches’, and the discourse they introduce, allow women who have been rendered invisible by social and cultural circumstances to recognize themselves in them, and to identify with them. In a sense they are like flagbearers or spokespeople for other women – so there is something more collective going on as well. I don’t think ‘bitches’ aspire to create a new feminist movement, but their position gives them a platform to shake things up and subvert norms of beauty, gender or race, for example.

Hélène Hiessler: Who is the ‘bitch’ talking to? Is she being heard?

Elena Diouf: In my view, she is talking to everyone, but particularly to people who don’t recognize themselves in her discourse. That may be why she causes such controversy and provokes so much debate.

Take Cardi B. Last summer she released a song with Megan Thee Stallion called ‘WAP’ which aroused intense criticism, particularly among conservatives in the US. The video is highly provocative. The lyrics talk crudely about sexual antics, erotic pleasure and so on, everything a patriarchal society seeks to suppress in a woman, especially a woman of colour.

It’s as if they were setting the record straight, as if they were saying: ‘Yes, I’m Black. Yes, I have big buttocks. But I’m rich, I love money and sex, and I do what I want’. In that sense, the ‘bitch’ – as I use the term – is talking to the whole world, and above all to people who do not recognize themselves in her discourse. They are precisely the ones who react most strongly against her.

The ‘bitch’ is talking to the public as a whole, but especially to the structurally racist and patriarchal society of the United States. Clearly, the message must be getting through – why else would she be causing so much controversy?