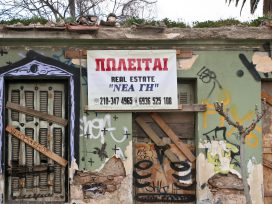

You have probably heard about the Skansen open-air museum in Sweden, but not about Euroskansen – The Museum of the European Way of Life. This is because it is currently under construction. In a few decades, tourists from all over the world, especially from China, will be touring Europe en masse. Their busses will stop in Brussels, Paris, Munich, Prague, Rome, Stockholm etc. Euroskansen will be offering guided tours specializing in every aspect of European life. It will provide the main source of income for the population of the Old Continent. Guides especially educated in Europeanism will tell visitors, often schoolchildren and students, how Europeans lived long ago. In AD 2050, this life will be considered a “paradise lost”. Visitors interested in printing, for example, will be able to inspect bookstores or newspaper kiosks and have the unique experience of holding books and newspapers in their hands. There will be public lectures and seminars organized in the typical manner: for free. Those interested in social services will be able to view hospitals with free medical provision, public schools and low-cost public transport. They will be introduced to the amazing concept of a universal pension system, as well as the fact that, only fifty years ago, Europeans enjoyed an annual paid vacation of up to six weeks long.

Many visitors will shake their heads in disbelief. “But how did Europe become a museum?” someone will inevitably ask. “At the beginning of the twenty-first century,” a guide will say, “the European Union experienced increasing difficulties on the global market. The EU fell behind in competing with the US and especially with the new economic powers such as China, India and Korea. In short, it collapsed economically, politically and socially because of the profit-driven economy, the weak state that could no longer control it and guarantee benefits to its citizens, as well as the expensive EU bureaucracy, which got bogged down in petty squabbles. The refusal to admit and to integrate immigrants, a workforce that because of the ageing population was much needed, was also decisive. Add to this the big picture of financial and ecological crisis and the general insecurity it created.”

“Politics was left to politicians motivated exclusively by private interest,” the guide will continue. “Their success or otherwise entirely depended on how popular they were. Infotainment, consumerism and individual concerns ruled – while common interests got completely lost, as in the rest of the world. Except that Europeans were used to the unique extravaganza of living in a society guided by institutionalized solidarity. This took the form of a set of policies based on the belief that all people should be guaranteed a minimum means in order to protect their human dignity. The state was therefore supposed to provide free education, healthcare, social benefits, pensions and more. In short, people strongly believed that it was possible to live together well as a community.”

“Unfortunately, in pre-Euroskansen times, there were no visions of how to protect these common goods, so people were forced to follow the dominant concept of endless economic growth, as well as deregulation and outsourcing. Not only were there no leaders capable of implementing a different vision – there was also nobody able to think differently. This happened because specialists in thinking, so-called intellectuals, died off as unnecessary at the beginning of the twenty-first century. A few did manage to survive in a remote part of France, a country once distinguished by its combination of social sensitivity and superb hedonism. One of them came up with a brilliant idea for how Europeans could survive, maintaining their way of life and even profiting from it! After visiting Stockholm – Skansen, to be precise – he returned to France and thought: ‘our continent is small and its population is old and shrinking, so why not turn the whole of Europe into Skansen? Then, the whole world would be able to come here and study our extravagant way of life…'”

“The rest is history. The buzz went around. The first reactions were against such a ‘zoo’, but soon the idea caught on with world politicians and business people. After a referendum (then a popular way out for politicians afraid to take unpopular decisions), in which 99.9% voted for the museum, Euroskansen became reality.” And thus the tourist guide will conclude his little lecture in the history of the European welfare state.