For a strong start into the second season, we talk about corruption in the EU. In the basement of the European Parliament we talk Italian mafia, Orbán’s son-in-law, and the misuse of public funding in member states with MEPs.

An art exhibition conjures up the silent spectre of the Holocaust in Hungary to explore apparently incompatible recollections, confront contradictory perspectives and engage with conflicting narratives.

As an emigrant from East Central Europe living in Austria, I have been exposed to a torrent of new experiences and challenged daily by an unfamiliar conceptual framework. Additionally, as an artist with an academic interest in memory studies, I have found myself facing and exploring different, often conflicting perceptions of the past.

In consequence perhaps, my recent art exhibition Chances in Life – Grandpa’s Backpack addresses the life of my paternal grandfather, Gyula Flohr. The project primarily reconstructs, through drawings, the environment in which Gyula’s experience was framed, examining family mementos and artefacts, and presenting interviews with his two children: János, my father, and Marcsi, my aunt.

Chances in Life presents some contradictory narratives recounted by family members on the one hand and the state on the other, pointing to nuances in social and gender relations, as well as the diminished life chances offered by the recurring closure of Eastern European societies. Yet these juxtaposed stories also demonstrate how, when ‘woven’ together, inconsistent and conflicting memories can be transformed, creating something new, complete and fully ‘interwoven’.

Consider, for example, Rivky Weinstock’s recollections of her grandfather (so far removed from mine):

I am sitting on the floor next to my cousins, looking up at my Opa with an expression of avoiding interest displayed on my childish face. It is Pesach night and it is two o’clock in the morning, but family tradition states that after every seder we sit around and Opa tells us yet another story of his experience in the Holocaust. He speaks and his eyes blaze with fire as he allows himself to relive the story. He weaves his words together beautifully, keeping us spellbound. Finally he concludes with a lesson that we as children can learn from that particular story.1

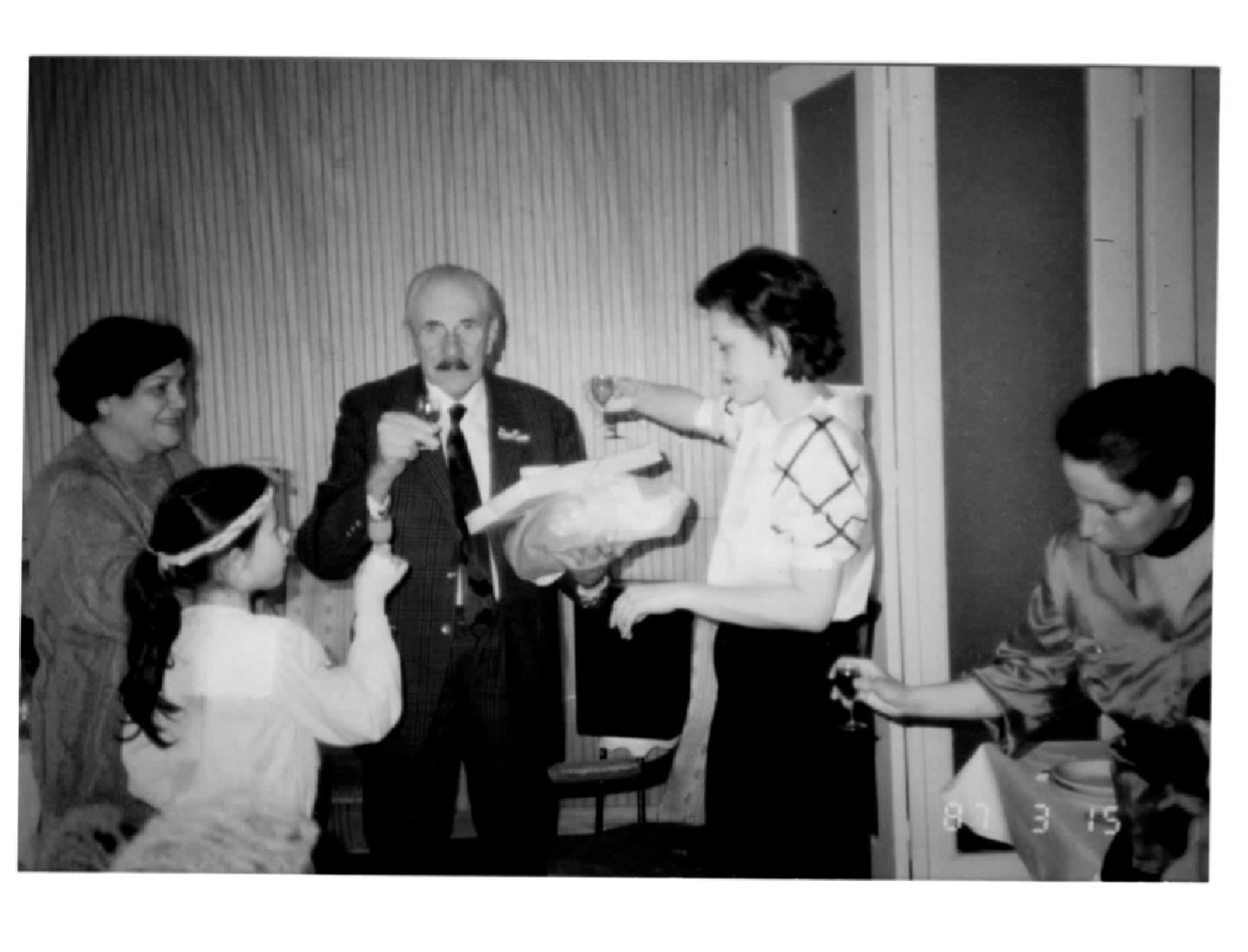

My grandfather on his 75th birthday surrounded by family (left to right; his wife, Magda Sőtér; me in yellow dress; my grandfather, Gyula Flohr; my aunt, Mária Flohr; and my mother, Éva Korodi), Budapest, 1987. Photograph: János Flohr

My own story begins very differently. We never celebrated Passover at home, and certainly not with my grandfather who had no desire to share stories with me or pass on any ultimate wisdom on the nature of life. He never said anything about the Holocaust. Indeed, my grandfather rarely looked at me when we met and, if he did, made it very clear that he was unhappy with the shape of my body. I was thin, my legs were like matchsticks and I was, as the Hungarian expression goes, ‘just a girl’.2

Consequently, I didn’t qualify as a real child. He would gaze at me briefly from a distance, then comment on my gender by way of complaint to my parents, or else remark on it in a worried sort of way to my grandmother. After that, I was expected to go up to him. He would grab me by the arms, with my body clenched in between, raise me, shake me, and put me down again. He would then instruct me to adjust the fringe of the carpet.This ritual represented the sum total of our relationship. My earliest memories of him date back to when I was four or five years old. By the time I was eleven, I had reached the height of one and a half meters, so he gave up shaking me. Shortly afterwards, he died.

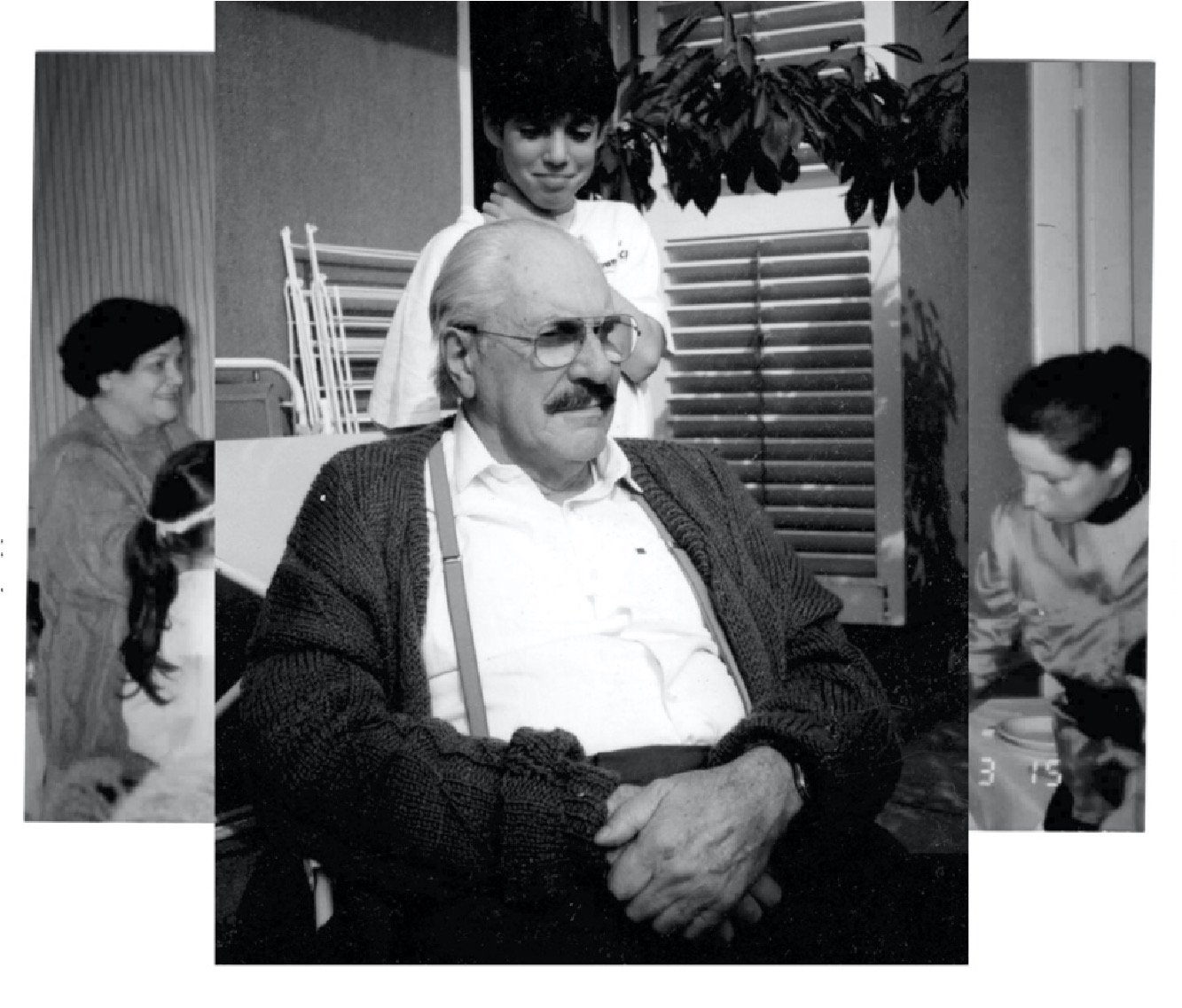

My grandfather and me, Leányfalu, c. 1992. Photograph: one of my parents. Digital collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

My grandfather was a tall man, as I remember him, silent and neatly groomed, with skin smelling faintly of soap. I was slightly afraid of him because he regularly shook me, and it hurt a bit. Now I know that it was just a game, a sign of his affection. But despite the tension that surrounds my memories of him, Gyula Flohr currently represents the artistic focus of the Chances in Life – Grandpa’s Backpack project.3 This centres around a number of absent objects which, according to family legend, played a major role in the story of my grandfather’s survival of the Shoah.

It was a story I originally compiled in my early teens from a range of anecdotes and remembered narrative fragments – for I have pondered the life my paternal grandfather led (before, after, and during the war) for many years. Although our relationship was distant, I was very close to his wife, my grandmother. She told me many things about their life, but she was not permitted to share anything about what happened to him during the war. My grandfather had decided not to talk about his experience of forced labour in Bor, or about how his family had perished in different concentration camps.

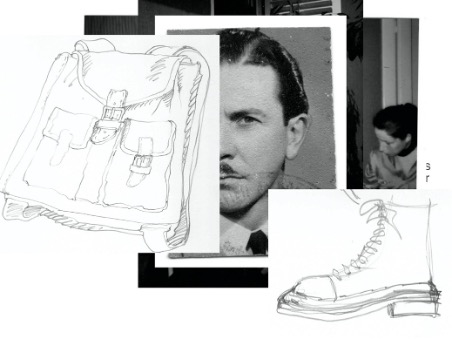

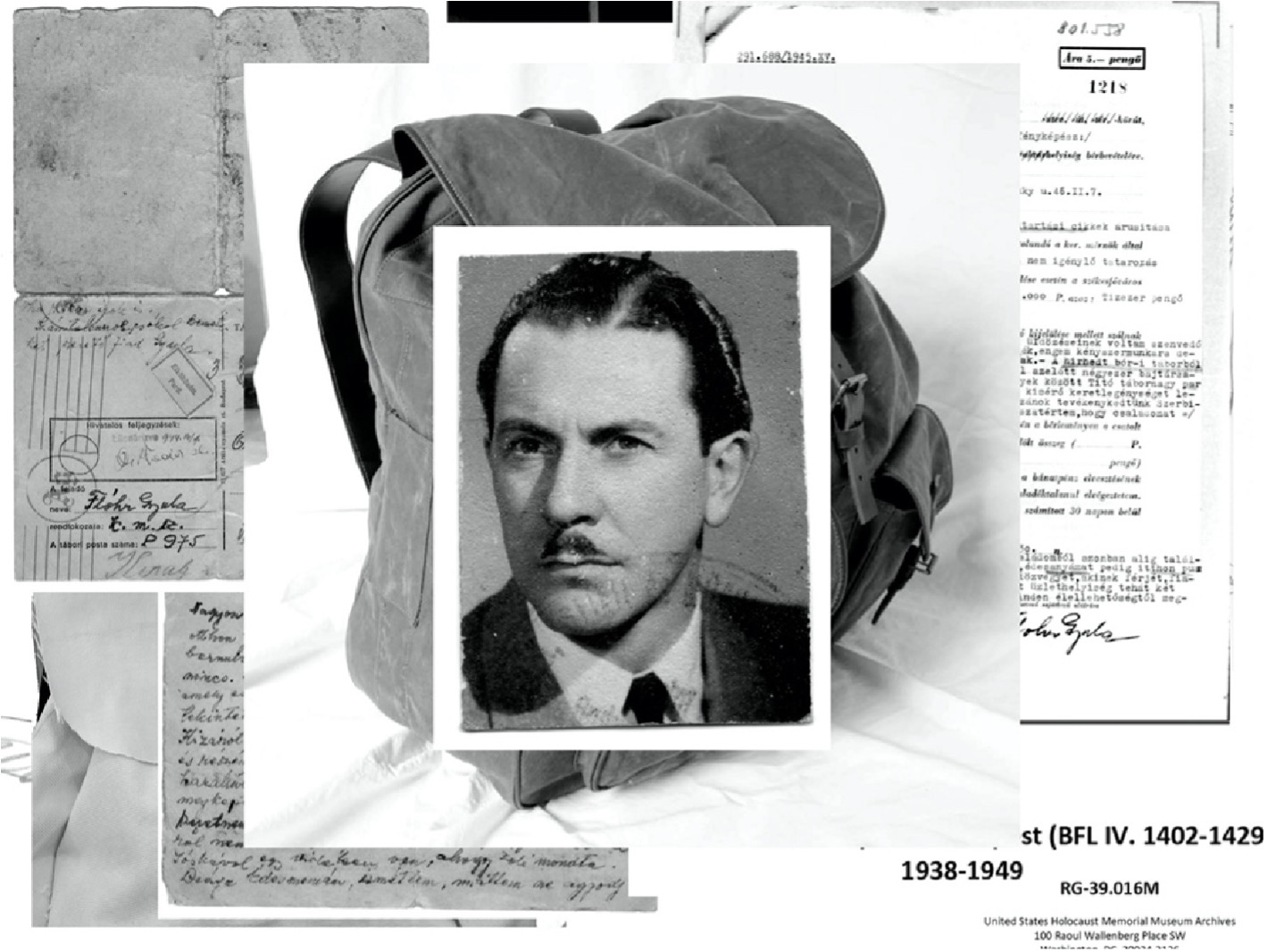

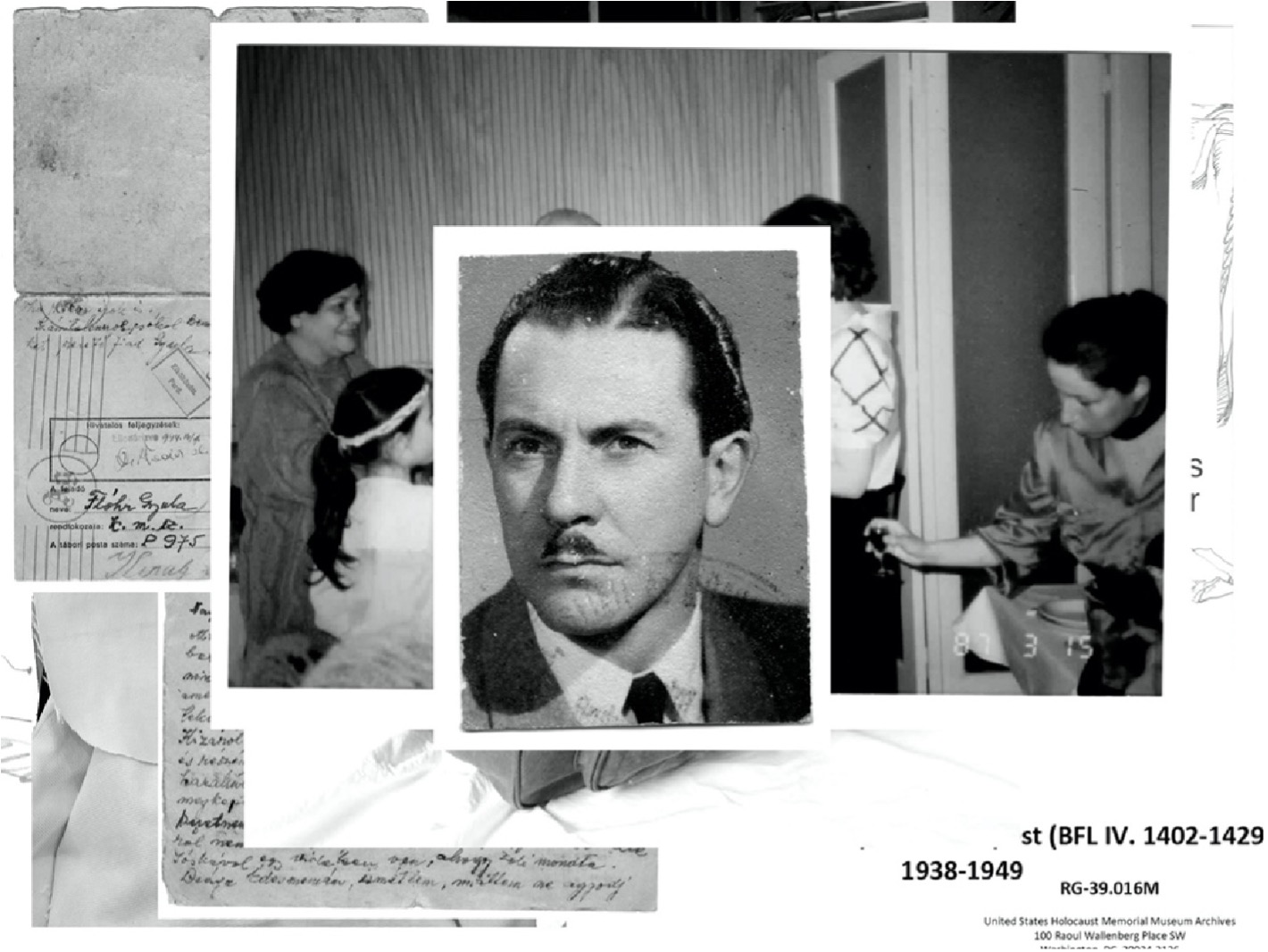

Digital collage with my grandfather’s ID/1. My Grandfather’s ID, c.1945. Digital Collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

All I knew about his life during the Shoah can be summed up in just a few sentences. In 1944, my grandfather was deported from Budapest to Bor, a mining town in Serbia, for forced labour. He had always loved high-quality objects, especially if they were meticulously crafted and, when he realized that deportation was a certainty, he ordered custom-made hiking boots from a shoemaker and a backpack with secret pockets from a tailor. It proved to be an investment that paid off. The hiking boots and backpack served him well during his time in forced labour. They saved his life in Bor and enabled him to survive the journey back to Budapest.

Later, as my father was growing up, these objects became the carriers of my grandfather’s story, which centred particularly around the diet of two sugar cubes and one litre of water per day on which he survived while walking home from Serbia to Hungary. When, a decade after the war, my father discovered the boots and the backpack, my grandfather found himself obliged to explain their unique shape and function. Unfortunately, in time, they were lost and I never set eyes on them.

My father’s drawings. Digital collage including my father’s sketch of my grandfather’s backpack and boots, 2017. Collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

This is as much as I have ever known about my grandfather’s fate during the war. No detailed list of workers enslaved in Bor exists and, thus far, my archival research has yielded almost nothing about his life there.4 My grandfather’s contemporaries, who might have witnessed the events, have passed away and all I know derives from accounts given by my father and my aunt. They remain the sole bearers of his stories. Even the objects that accompanied my grandfather through deportation, forced labour and the long trek back to Budapest have disappeared. Today they exist only in the memories of my father and my aunt.

As I began work on the Chances in Life exhibition, I once again took up my research. I sat down with my father, asked him about the way he remembered my grandfather’s backpack and recorded the conversation. My father recalled that, on one occasion, he wore the backpack while hiking as a child and his shoulder swelled up afterwards. Back home, after the hike, my grandmother asked her husband why the backpack was so heavy, at which point my grandfather realized that the sugar cubes he had sewn into the shoulder straps in 1944 were still there.

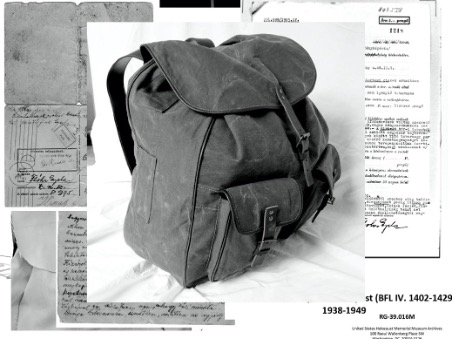

Re-crafting the backpack. Digital collage including my father’s drawing alongside my digital photographs illustrating the process of making the replica of the backpack, 2017. Collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

As we talked, I asked my father to draw the backpack from memory. The process went hand in hand with a series of interviews I conducted with him, and lasted several weeks. My father had inherited a love of well-crafted objects from my grandfather, so I asked him to concentrate on detail as he drew. I then asked a tailor, who still retains the skills to create bespoke items, to make further sketches and a model of the original backpack using simple material, based on my instructions and drawings. Meanwhile, I discovered written evidence that my grandfather had been taken to Bor, but subsequently escaped and joined the partisans.5 My aunt also found two letters in her cupboard, written by my grandfather from Bor, to his mother.

When, at last, the reconstructed backpack was finished, I showed it to my aunt. She was critical. ‘Well, it’s nicely done,’ she said, ‘but it’s nothing like the original.’ At this point it dawned on me that I should also take her perspective and narrative point of view into account, so I initiated the same process of interviews with her.

Backpack No. 1 based on my father’s drawings. Digital collage with photograph of backpack, 2017. Background shows letters from Bor, written by my grandfather. Document of my grandfather’s shop rental request from 1945. The last one is from the Archives of United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, DC. Collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

As I compared the two sets of interviews, I became aware of sharp contradictions in their stories. My father had built up an image of his father as a hero, while my aunt seemed to perceive my grandfather as an anti-hero, who had negatively impacted the family as well as her personally. There were also contradictions in dates and facts, the shape and the size of the backpack, the size of the sugar cubes in it, what my father and aunt knew about Gyula’s life before they were born, how they remembered him as children and, subsequently, how they viewed him as adults.

Chances in Life – Grandpa’s Backpack was sparked by my desire to fill the memory gaps in family history, and to reconstruct my grandfather’s personality. I wanted, retrospectively, to try and get to know him, to uncover the ‘truth’ about him. But I was alone. Neither my father nor my aunt wanted to talk about their father, and agreed to do so only when pressed. They seemed caught between a need to revisit their memories and an urge to keep silent. The process of remaking the backpack had turned a remembered object into a symbol bearing a reconstructed family history. The contradictions and disagreements between my father and aunt point to a highly problematic, though also compelling, aspect of memory studies. In Hungary and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe, memory work by the second generation – the generation of ‘postmemory’ spanning the lives of my father and aunt – is frequently lacking. Clearly, every such story is bound to be embedded in a family history, but it is also important to realize that, for us, my grandfather became the paradigm of a specific time and place. The contradictions and conflicting accounts I heard as I conducted my interviews, prompted me to choose my grandfather’s story to illustrate the ‘interweaving’ of memories: the process of aligning and interlacing fragments of historical research and conflicting narratives, which point to past, present and future, and gradually form a ‘woven memory.’

Even though their knowledge about my grandfather was so limited, the lives of both my father and my aunt were indelibly marked by Gyula’s story and his experience. And yet I felt the story was not really theirs, partly because there was so much they did not remember, and partly because they had never pursued what they knew. The responses my aunt and my father gave to the project were neither self-evident nor smooth, for my bluntly masculine grandfather had impacted their lives very deeply. They were not entirely opposed to the interviews, but my aunt in particular found it difficult as we began our dialogue about my grandfather. Nor did she find the conversation any easier when my father later joined us. It gradually became clear to me that the project, and our ensuing intergenerational discussions on the Holocaust and forced labour, had compelled my father and aunt to take possession not just of their father’s story, but of their own personal histories. For the first time in their lives, they exchanged thoughts and information about their father and the times in which he lived. The most interesting outcome of the art project and exhibition proved to be the dialogue between myself, my father and my aunt, displayed alongside drawings depicting the built environment in which my grandfather once lived.

The exhibition’s order was reverse-chronological, starting with my grandfather’s later years and ending with his youth. At each stage an interview between my father and my aunt was shown, exposing contradiction, conflict or agreement. As gaps in the family narrative of the Holocaust emerged, they served to re-position my grandfather’s legacy in both positive and negative ways, revealing that a single coherent narrative might not exist. Reflecting on intergenerational trauma, Melissa Kahane-Nissenbaum argues that ‘the third generation appears to be reconstructing their grandparents’’ history and resurfacing their legacy. In so doing they are coming to understand the strength their grandparents’ generation demonstrated, and the heroic battles that had to be fought to get their descendants where they are today.6

The attempt to reproduce my grandfather’s backpack aimed (ultimately impossibly) to reconstruct his personality and life story, and to humanize him. To me, it felt like weaving different materials in a loom.

Digital collage with my grandfather’s ID/2. Collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

At one point I began to call the process an ‘interweaving’ of recollections, resulting ultimately in the concept of ‘woven memory’. While working on the Chances in Life – Grandpa’s Backpack exhibition, I discovered that my sources were primarily fragmented images and stories, difficult to match and understand. There were many narrative gaps, partly because material has disappeared over time, and partly because there were no longer any family witnesses left. I had to fill in these gaps by relying on written history, the testimonies of other inmates from Bor, films, and archival photographs. As I wove together the strands of family memory and narratives from secondary sources, a few gaping holes remained. I found myself obliged to fill them, and consequently several threads in the narrative derive solely from my imagination. The result is a complex tapestry of ‘woven memory’.

Commenting on writers of the third generation, Megan Reynolds remarks that their literature strives to describe lost worlds while at the same time demonstrating uncertainty about how to portray the Holocaust. Faced with this troubling conflict, and trying to piece together fragments of memory, the third generation have incorporated imagined elements to fill in the gaps.7 My own imagined world is populated by ghosts of past stories, objects that have disappeared, photographs never seen, letters never read, abandoned spaces of intimacy or horror, homes without addresses, missing information, and the shadows of nameless people who were unable to say goodbye. By interlacing reported narrative elements, research findings, and my own imagined impressions, I strive to create a multithreaded portrayal. Some sections form an integral image while other fragments remain solitary and apart. Woven memory is a process. ‘When a traumatic experience is put into classical narrative’, Tatiana Weiser writes, ‘the text itself undergoes the following changes: it rejects linear narration, plot, or conflict; its syntax breaks into segments or becomes deformed’.8 I have woven together different materials, illuminating the gaps and highlighting the pitfalls they present. Non-linear narratives reflect the conflicting stories that arise in the course of remembering. I chose to show these broken stories, images, fragments and layered archival materials, arranged much like the collages that illustrate this article, and in so doing sought to demonstrate that the weaving process itself is punctured and flawed. If it is sometimes successful, parts of the resulting fabric are bound to be woven incorrectly.

Digital collage with my grandfather’s ID/3. Collage by Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

As a Jewish woman in Budapest, I have frequently felt a sense of ‘otherness’ elicited by my name or my appearance. When I moved to Vienna (a far more diverse city than Budapest) in 2014, for the first time ever I experienced myself as ‘white’.9 My looks blended easily with the majority of the population. At the same time, because I didn’t speak German and my English was relatively poor, I often felt socially ostracized and uncomfortable. This curious juxtaposition of apparent acceptance and underlying unease fundamentally shaped my experience and continues to do so today. In Vienna, I underwent a process of learning to understand what it is to be an Eastern European in the West. Moving here meant leaving a world of familial and local memory, and having to transfer or translate all I knew into a different cultural and linguistic framework. In Vienna, I came to think about art as a space for knowledge production, for sharing different narratives and trying to understand diverse histories. As I crossed the border and switched cities, I encountered in Vienna a transnational space where disparate memories of genocides, colonization and slavery could no longer be delimited or separated.10 Shuttling back and forth between a traditionally East-Central European country and a West European one – Hungary and Austria – I experienced different notions of memory and varying strategies of commemoration, alongside shared though also divergent histories.

My migration meant that a new realm of ‘affiliative postmemory’ had opened up for me. As Marianne Hirsch writes:

To delineate the border between these respective structures of transmission – between what I would like to refer to as familial and as ‘affiliative’ postmemory – we would have to account for the difference between an intergenerational vertical identification of child and parent occurring within the family and the intragenerational horizontal identification that makes that child’s position more broadly available to other contemporaries… It is the result of contemporaneity and generational connection with the literal second generation, combined with a set of structures of mediation that would be broadly available, appropriable, and indeed, compelling enough to encompass a larger collective in an organic web of transmission.11

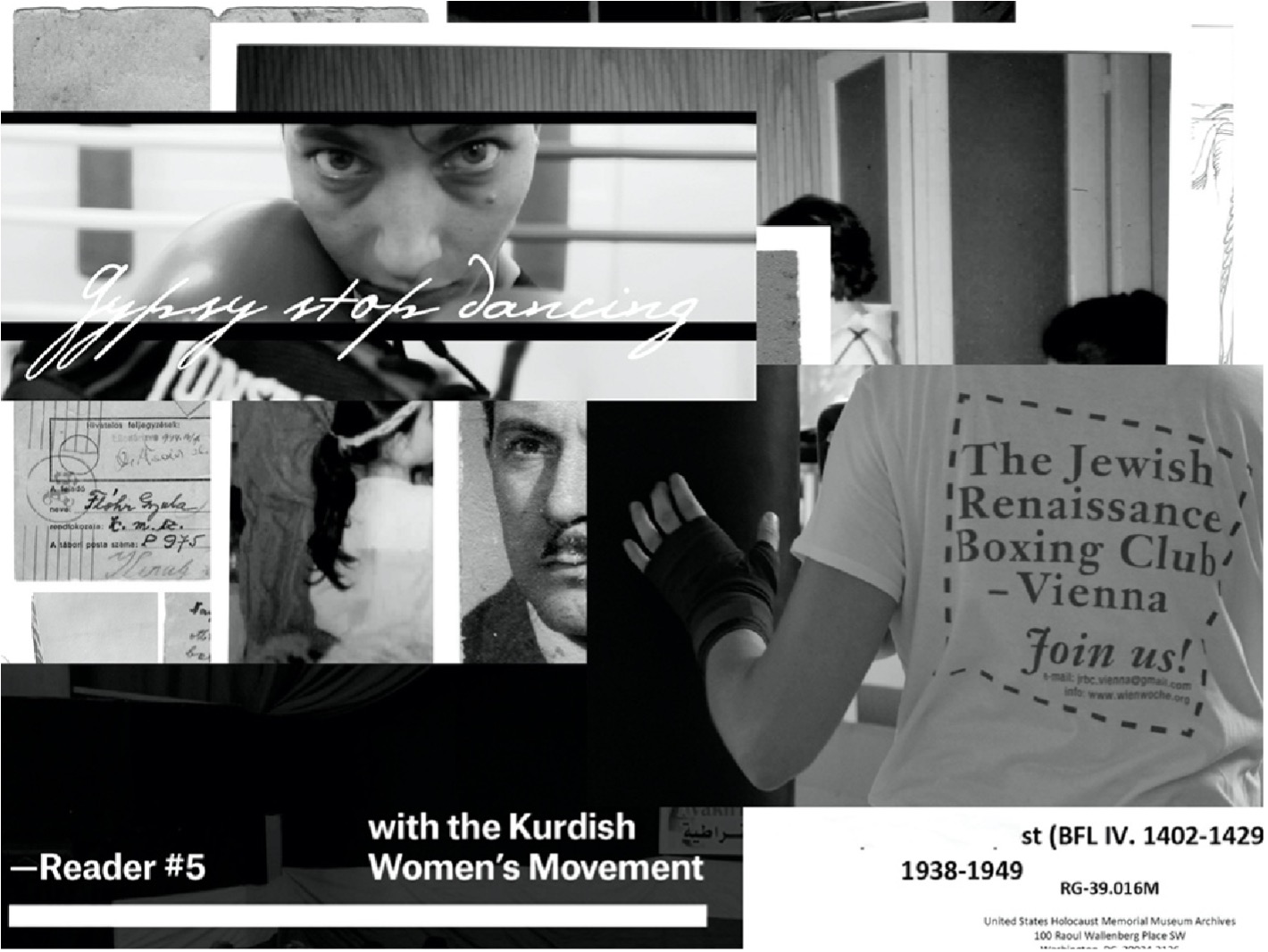

Digital collage bringing together different projects I created, or was inspired by. This includes The Jewish Renaissance Boxing Club (Zsuzsi Flohr, Tatiana Kai-Browne, Veronica Lion and Sarah Mendelsohn, Vienna, 2014), Gipsy Stop Dancing (a project by Romano Svato, 2011), New World Academy Reader #5: Stateless Democracy (design by Remco van Bladel, 2015). Collage: Zsuzsi Flohr, 2018

Stepping out of familial postmemory has meant that I have had to address a number of questions. What does it mean to leave a locality, familial discourse, a native language? How can I, who have left, connect to others’ histories? Who, in turn, can connect to my own story? The borders and constraints of interweaving different memories and histories became a serious challenge for me. I saw that the weaving process often led to splits between groups and had to ask myself: what can I do about these divisions? How are these conflicts to be addressed?

In recent years, while participating in discussions about my art projects in Vienna, I have encountered the limitations of connectedness and been faced with the question of how much interweaving memory can take. When does ‘woven memory’ become an illusion? At times, I have wondered whether the dialogue that is needed is possible at all. In order to connect with different approaches to memory politics, it is important to highlight exiled, unspoken, and hidden narratives. As we emigrate and immigrate, histories migrate with us. In so doing, they may conflict with and challenge one another. Innovative approaches raise new questions and create possibilities for linking differing constructed histories, all of which appear so exceptional and unique.

As I interweave memories, I want to tread this horizontal line further, for it is a conceptual extension of affiliative postmemory. I claim it for the third generation and their contemporaries, for the space where different histories and traumas meet, and where they could potentially keep company. I want to see how lines of affiliation cross, connect or strengthen divides and borders. In the process of interweaving different recollections, I want to emphasize the importance of the ghosts of times past and the spirits of different, hidden narratives. As an artist, my work explores the potential of conjuring spectres from the past in order to engage with them in the present. Where different histories collide, it is hard to avoid clashes of memory. Giving serious attention to the concept of ‘woven memory’ implies thinking about how these ghosts can be permitted to meet and confront one another in a single space, populated by different people with diverse identities and differing histories.

Rivky Weinstock, Twice Buried Still Alive: Yitzchok Donath’s miraculous story of faith and survival as told to his granddaughter, Targum Press, 2006, p. 12.

The Hungarian expression ‘nem gyerek az csak lány’ translates as ‘she’s not a child, merely a girl’.

Életlehetőségek [Chances in Life] an exhibition by Zsuzsi Flohr, 2B Gallery Budapest, 22 November 2018 - 6 January 2019. See: http://www.2b-org.hu/ eletlehetosegek/info_English.pdf interview at the Klubrádió by Réka Kinga Papp; https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvC3u08xOTU review at Artportal by Hedvig Turai https:// artportal.hu/magazin/az-.- eltunt-.-targy-.-nyomaban/

Tamás Csapody has collected almost all the names of labour servicemen of Bor. ‘During World War II about 6000 Hungarian labour servicemen were taken to Bor, Serbia. According to the Hungarian-German agreements, 94% of the two large groups of labour servicemen who were gathered and transported in 1943 comprised labour battalions conscripted from the entire country. The second group of Jewish labour servicemen - who came mainly from Budapest and the younger ones from Jászberény and Vác – were transported to Bor by train after the German occupation of Hungary’ in March 1944 (Tamás Csapody, Bortól Szombathelyig - Tanulmányok a bori munkaszolgálatról és a bori munkaszolgálatosok részleges névlistája [From Bor to Szombathely- Studies on the Forced Labour Service at Bor Camp and the Partial List of the Forced Labourers in Bor], Zrínyi kiadó, 2014). My grandfather was in this second transport.

See: RG-39.016M, Records of the Mayor of Budapest (Budapesti Fővárosi Levéltár IV. 1402-1429), 1938-1945.

Melissa C. Kahane-Nissenbaum, Exploring Intergenerational Transmission of Trauma in Third Generation Holocaust Survivors, University of Pennsylvania, Doctorate in Social Work (DSW), 2011, 16.

Megan Reynolds, “Constructing the Imaginative Bridge: Third Generation Holocaust Narratives,” American Journal of Undergraduate Research, Vol. 14, No. 1, April 2017.

Tatiana Weiser, “What Kind of Narratives can Present the Unpresentable,” Martin Davies and Claus Christian W. Szejnmann (eds.), How the Holocaust Looks Now: International Perspectives, Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, p. 210.

In Vienna, I have been repeatedly exposed to the question: are you white or a PoC? This was one of several contradictory experiences I have had in social situations here, and I have often wondered what prompts people to ask a white person whether s/he is white or PoC. Finally, I learned that some emigrants from former Yugoslavia, or other parts of the erstwhile communist bloc, identify themselves as marginalized and use the concept PoC to describe their perception of their position in Viennese or Austrian society. This is clearly a complex situation that deserves closer examination. It is, however, outside the scope of this article.

As Michael Rothberg has pointed out, we are all the ‘implicated subjects’ of our shared histories. Michael Rothberg, The Implicated Subject: Beyond Victims and Perpetrators, Stanford University Press, 2019.

Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust, Columbia University Press, 2012, p. 36.

Published 7 October 2021

Original in English

First published by Alice Balestrino ed. 'Past (Im)Perfect Continuous. Trans-Cultural Articulations of Postmemory of WWII', 2021 Sapienza University Press

© Zsuzsi Flohr / Sapienza University Press / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

For a strong start into the second season, we talk about corruption in the EU. In the basement of the European Parliament we talk Italian mafia, Orbán’s son-in-law, and the misuse of public funding in member states with MEPs.

Since the war in Ukraine, the Visegrád Four group no longer articulates a common voice in the EU. Even the illiberal alliance between Hungary and Poland has come to an end. Yet in various ways, the region still demonstrates to Europe the consequences of the loss of the political centre.