Who’s going to vaccinate Roma people?

Scapegoated early on in the pandemic, Roma communities do not get the full support they need to participate in vaccination campaigns. Distrust of inaccessible health care systems, built to exclude minorities living outside the mainstream, is a major obstacle.

According to Jonathan Lee, of the European Roma Rights Centre (ERRC), the vaccination willingness of Romani people is very low throughout Europe and most governments do not seem to care much for them. In Slovakia, mobile units were established to supply isolated communities, but other countries did not pay much attention to Roma. This is despite the European Commission’s vaccination guideline calling on member states to prioritize vulnerable socio-economic groups, a category which includes the Roma population in every European country. Lee says:

Within and without the EU, it is distressing to see how Roma are neglected in the vaccination campaigns, quite like they were neglected during the entire pandemic. European authorities also disregarded Roma when emergency measures were introduced.

Financial measures have been taken to support certain social groups and labour markets, but European Roma and people living in deep poverty have not been targeted with aid or relief. Moreover, there were explicitly discriminatory actions against Romani people in Bulgaria, Slovakia, and Romania, scapegoating them as a risk for public health.

Spraying from helicopters

Bulgarian activists, for example, reported a case to AP where Roma majority villages were sprayed from helicopters and airplanes with thousands of litres of germicide used for plants. Radoslov Stoyanov, the representative of the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee’s human rights team, says these incidents were obviously motivated by racism as only villages with a high Roma population were ‘disinfected’ with such methods.

In May, two UN human rights experts sent an open letter to the Bulgarian government calling on them to cease pandemic-related police operations in Roma villages and settlements and to end the practice of hate speech against them, after the leader of one of the nationalist parties called Roma communities the nests of infection.

Photo by Adam Jones adamjones.freeservers.com, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Bulgaria, however, is not the only country blaming the pandemic on Roma people. A mayor in eastern Moldova also declared that Romani communities spread the virus, whereas a Ukrainian official instructed the police to remove all Roma people from town. Western Europe had its share of racism too: the mayor of a French village asked people to contact the French government if they saw ‘a caravan wandering around’ (referring to Romani people with the phrase).

Last year the autumn report of the European Roma Rights Centre documented 20 cases in 5 countries of disproportionate use of force applied against Roma people for not complying with public health regulations.

The Slovakian exception

Jonathan Lee reminds that accessibility is only one problem area for Roma communities. What matters even more is that Roma people are inherently excluded from social services. They are met with racism in health care institutions; many of them do not even have health insurance; and segregated communities tend to be isolated in remote areas, far from hospitals or even GPs. In certain countries, like Ukraine, North Macedonia, and Moldova, many of them lack documents like identity cards, so their access to public services and health care is limited.

Slovakia is the only country to have designated Roma people as a high priority group in the vaccination campaign, because of the high ratio of underlying conditions among the population, such as cardiovascular diseases, severe disability, respiratory diseases, diabetes, asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, and illnesses related to obesity.

Romani people constitute one of the largest minority in Slovakia – official census data accounts of them as 2 per cent of the population, but due to the high latency of centralized surveys, all expert estimates are much higher. According to the European Commission’s estimate, about half a million people, 9 per cent of Slovakia’s population are Roma.

Although vaccination willingness was also very low in Slovakia – a survey in December indicated that 75% of the population was unwilling to get the vaccine at that time – the Slovakian government made extra efforts to convince the Roma in particular. With the aid of civil activists, mobile units were established to visit Roma settlements.

A useful diversion

Hungary fared relatively well in the first and second waves of the pandemic, but from late January new COVID infections and deaths increased so fast, that by April the Hungarian mortality rate was the highest in the world. The government was reluctant to acknowledge the fast spreading new variants in the neighbouring countries even in February, so no specific measures were taken, not enough tests were conducted. Moreover, the government initiated a ‘national consultation’ about the reopening – another round of Fidesz’s signature propaganda campaign.

Amid growing public concern, schools weren’t closed, shopping centres and casinos were up and running while hundreds of lives were lost daily due to coronavirus. The government introduced restrictions only in March, and this delay of a month and a half resulted peaks of over 11 thousand new infections and 311 victims per day in the third wave. More than 30,000 people have lost their lives so far to the pandemic in Hungary, a country of less than 10 million people.

The Fidesz government never admitted to a mistake, and decided to divert attention during the third wave with a vaccination frenzy, sometimes disregarding protocols or scientific processes. Instead of waiting for vaccines obtained and approved by the EU, they contracted China for the Sinopharm vaccine and Russia for the Sputnik V vaccine.

Both were launched in Hungary at a time when many other countries found it disquieting that their full documentations weren’t made available. Still, their approval was fast-tracked by the Hungarian authorities. Moreover, many elderly people got the Chinese vaccine, although it was used even in China only for people younger than 65 years.

Initially, Hungarians distrusted the Chinese and Russian vaccines, but the government tried everything in their power to convince people about their safety, even at the cost of damaging the reputation of western vaccines. For example, the government published confusing data about the effectiveness of vaccines, which suggested that the Russian and Chinese vaccines would be more efficient than Pfizer because fewer among their recipients got sick or died after getting the jab. This comparison, however, did not reflect the fact that a lot more people had received the Pfizer shot by that time than any other vaccine, and that Pfizer was the choice for groups most vulnerable to the virus – people working in health care and social services, and the eldest layer of society.

An obvious bottleneck

Although the speed of vaccination was truly higher in Hungary than in most other countries (only Malta did better for a long time), organising the vaccination did not go without problems, since the government burdened GPs with organising the rollout, including the bureaucratic tasks. General practitioners have had to call their patients one by one to let them know that they could get the vaccine, often also trying to convince the patient to accept the available shot.

This process was problematic for Roma communities, as not all of their members have mobile phones on which they could be contacted, let alone well-established relationships with GPs.

By the end of May, more than 5 million people were vaccinated, but vaccination willingness has declined in June. Despite the government’s decision that numerous facilities can only be used by those who have received their vaccination certificate, there is no real hope for getting more than two thirds of the population

Although the speed of vaccination was truly higher in Hungary than in most other countries (only Malta did better for a long time), organising the vaccination did not go without problems, since the government burdened GPs with organising the rollout, including the bureaucratic tasks. General practitioners have had to call their patients one by one to let them know that they could get the vaccine, often also trying to convince the patient to accept the available vaccine.

This process already problematic for Roma communities as not all of their members have mobile phones on which they could be contacted, let alone well established relationships with GPs.

By the end of May, more than 5 million people were vaccinated but vaccination willingness has declined in June. Despite the government’s decision that numerous facilities can only be used by those who have received their vaccination certificate, there is no real hope for vaccinating more than two thirds of the population, roughly 6 million people.

In January, only 9 percent of the Hungarian Roma people wanted to get a corona vaccine, according to a research by the University of Pécs. Ernő Kadét of the Roma Press Centre reminds that virus-scepticism and anti-vaccine sentiment is present among the Romani people as well. Those who live in isolated villages and poorly educated people are far more vulnerable to fake news and conspiracy theories. For uneducated people it is ‘difficult to find their path in the jungle of fake news’, Kadét says.

Roma people also tend to distrust the Hungarian health care system, for example because they have experienced discrimination there. Those who live in isolated or segregated villages hardly ever see general practitioners, as these positions often remain unfilled in such poor districts. It’s not uncommon that a doctor is available only for a few hours a week.

A further problem is distance. Vaccination sites are often 50, 60 or even 100 kilometres away, and people living in extreme poverty cannot afford bus or train tickets.

Ernő Kadét assumes that many Roma might also feel strongly against anti-virus measures and vaccination because the economic effect of pandemic restrictions afflicted them the worst as they lost opportunities of casual employment.

Gábor Tamás Koronczi, a general medical practitioner in Osztopán, sees registration as the greatest obstacle:

There are very few computers, and even those who have one might not be able to create new e-mail accounts for all their family members, but one e-mail address can be used only for the registration of one social security number. Contacting people via phone is also problematic, since even people who have a cell phone cannot necessarily always use them as they often don’t have the money for prepaid cards – but that is rather an issue of organising the vaccination.

The local authority tries to help with registration, but Koronczi says that many people come to his office to register because that seems logical for them. They also prefer getting the vaccine in his office as they are reluctant to travel to vaccination sites. To assist them, the minibus of the local authority is used for transporting elderly or physically disabled people to the doctor’s office or to vaccination sites.

Koronczi notes that most of the elderly people in the local Roma community he is serving have already been convinced and vaccinated, and there are more and more working Roma people registering week by week, thanks to the help provided to them.

Futile billboards

Since December, the Hungarian government has spent almost 80 million euro on ads related to the coronavirus, including a campaign featuring celebrities stating that vaccines save lives. However, Ernő Kadét thinks that such initiatives can’t convince poor people, who tend to suppose that famous people only join the campaign for money.

According to Kadét, online registration makes the access to vaccination very difficult for Roma people; it would be more useful to offer walk-in vaccinations at general practitioners’ without registration. The most recent re-opening rules demand a vaccination certificate to access indoor dining and other public spaces, but this is not the ideal incentive for the Roma: people living in extreme poverty do not have the money to attend public places of entertainment in the first place.

The campaign Oltass, hogy élhess (‘Vax to live’) was launched to alleviate these issues through the cooperation of numerous NGO and civic groups.1 Their volunteers visit Roma settlements, trying to overcome skepticism and helping them with registration. They share memes on social media, featuring Roma celebrities as well as health care professionals involved in their campaign.

Campaign short for Oltass, hogy élhess! (Vax to live!) featuring prominent Roma intellectuals and celebrities, talking about rtheir experiences with COVID-19 or the vaccine, calling on Hungarian Roma to register and take the vaccine.

The first phase of the campaign has just been completed, and Ernő Kadét believes that its effects are significant, but there is still much left to do. He reminds that in communities where the contagion has spread and taken lives, most people are ready to accept the vaccine, whereas it is far more difficult to persuade the residents of settlements where people only heard about COVID in the media.

Eroded trust

The German Open Society Roma Initiatives Office claims that there are 150 thousand Roma people registered in Germany, but a lot more living in the country, invisible for the system. According to Euronews, there are about 50,000 people in Greece who have no access to public health care, and most of them are of Romani descent.

Jonathan Lee confirms that Roma people have good reasons to distrust authorities, who only interact with them in case of alleged crimes:

In Hungary we’ve seen ambulances refuse to enter villages with a Romani majority, and the ERRC also investigated cases in hospitals where the staff verbally abused Roma mothers giving birth. Forced sterilisation still occurred in Hungary as late as 2001 and in the Czech Republic even in 2012. If Roma people’s experience with authorities is restricted to abuse and discrimination, why would they immediately trust the same authorities encouraging them to get vaccinated?

The ECCR concludes that public health information campaigns need to focus on particular target groups, for instance trying to restore the trust of Roma communities. Governments and decision makers should have realized the unique difficulties of these communities and acted to ensure that everyone has equal access to vaccination.

This article is an extended version on the author’s piece in Hungarian for 444.hu, published on 24 May 2021.

Cooperating organisations include: aHang, Dikh TV, RomNet, Roma Press Centre, The System Level – National Community Organizing Workshop, Civil College Foundation, 1 Hungary Initiative, and the National Roma Council.

Published 22 June 2021

Original in Hungarian

Translated by

Katalin Szlukovényi

First published by 444.hu (Hungarian version); Eurozine (English version)

© Kitti Fődi / 444.hu / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

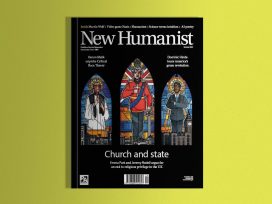

The state of the Church

New Humanist 2/2023

Turing off the tap for the Church of England: why state support for English Anglicanism belongs to the past. Also: Kenan Malik on the flaws of critical race theory.

White supremacist rhetoric can quickly lead to violent acts. At their most extreme, theories about the decline of white dominance, the emasculation of western society, elite betrayal and a calculated ‘great replacement’ incite a perceived right to kill. Defining the psychology behind far-right mass murderers highlights a terrifying mix of fear and racism.