What's in store for the Siberian movement?

Siberian neo-regionalism has recently gained momentum, writes Stanislav Zakharkin; a development fuelled not least by widespread concern about the uneven distribution of revenues from the region’s oil and mineral resources. But is this diverse grassroots movement capable of effecting real change?

In recent years, the so-called Siberian movement has started to gain in popularity to the east of the Ural Mountains. The movement was born in the late 2000s in the regions, among a predominantly ethnic Russian population, and is becoming more active every year. 4100 people identified themselves as Siberians during the population census in 2010 – a 400 per cent increase on the previous census in 2002.1 It is probable that this increase is related to the information campaign “Siberian is a nationality!”, carried out by activists of a virtual movement called “True Siberians”. In addition, the number of people who did not indicate their nationality in 2010 sharply increased by more than four million people, as compared with 2002 – when 1.46 million people across Russia did not indicate their nationality.2 This, despite the fact that the total population of Russia decreased by 2.31 million people during the same period. Activists in the Siberian movement claim that many of the 5.63 million “people of no nationality” are Siberians, whose existence the federal government chose to ignore.

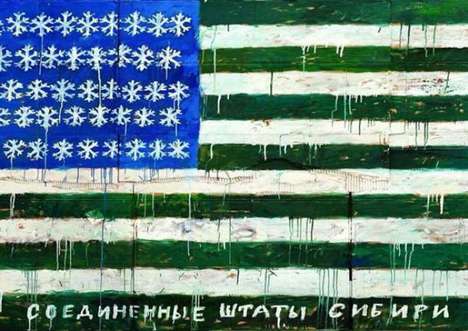

From the exhibition “The United States of Siberia, spring 2013, Novosibirsk.

The historian Marina Zhigunova wrote an article in 2011 entitled “Siberian as a new nationality: Myth or reality?”, where she reports on the positive dynamics of building Siberian regional identity in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Zhigunova found that only 15 per cent of respondents identified themselves as Siberians during the period from 1986 to 1988, when asked “What would you call yourself?” However, in 1994, 19 per cent of respondents identified themselves in this way, 32 per cent in 2000, 52 per cent in 2005 and 75 per cent in 2010.3 The strongest support for the idea of “Siberian identity” was found mainly in the ethnic-Russian regions of Siberia. The residents of the autonomous republics who were interviewed preferred traditional markers of national identity. For example, only 42 people in Buryatia (one of the largest autonomous republics of Siberia) were willing to identify themselves as Siberian.4 So, what is the reason for the growing popularity of the Siberian movement? What is the fundamental difference between “Siberian” and “Russian”? What political consequences might the Siberian movement have for the Russian Federation?

Ideology of a Siberian regionalism

The first attempt to make sense of Siberia as a specific region within the Russian state was made by Siberian intellectuals in the 1850s. At which point, the ideology of Siberian regionalism was born, and continued to develop until 1917. As regionalism evolved, the concept of Siberia’s territorial autonomy emerged, along with the idea of its separation. Regionalism was born in a St. Petersburg circle of Siberian students that included Nikolai Yadrintsev, Grigory Potanin, Nikolay Naumov, Seraphim Shashkoff, Fedor Usov et al. Yadrintsev had described the key features of the relationship between Siberia and the imperial centre in his book “Siberia as a colony” (1892):

1) The imperial centre had a monopoly on the region’s land and natural resources.

2) Up until the early twentieth century, the region was predominately used as a “penal colony”. According to Yadrintsev, among the four million inhabitants living there in the 1870s, 500,000 were convicts.

3) Trade between the Siberian regions and provinces in European Russia was unequal. Up until 1913, a so-called “Chelyabinsk tariff plan” was in force. It had been adopted in order to reduce competition between grain producers based in European Russia and Siberian ones. When crossing the Ural Mountains to sell their grain in Russian or international markets, Siberian producers had to pay a special fee. So in Moscow and St. Petersburg, Siberian grain was 30 per cent more expensive than grain from the Volga delta or from Ukraine.

4) Local authorities were appointed by the imperial centre, had no connection with the interests of the local population, and considered their “service in Siberia” only as one step along the way toward personal enrichment.

5) The imperial centre strongly opposed the furthering of science, education and culture in the region, which stimulated an exodus of young people wishing to take up places in universities in European Russia; this acted as a break on the emergence of local intellectual elites.

In addition, Siberian people were discriminated against in respect of their civil rights, as compared with people in central Russia. Russian judicial reform in 1864 spread to Siberia only in 1897, while local self-government (created in European Russia in 1864) was denied to Siberians until 1917.5

Nevertheless, in emphasizing the oppression of Siberians, Siberian regionalists also pointed out how much Siberians differed from other Russians. The prominent regionalist Gregory Potanin proposed that Siberians were likely closer to American pioneers and colonizers in terms of their mentality, than to the inhabitants of the rest of Russia. According to him, on the one hand, Siberia like America is largely populated by exiles. On the other hand, Siberian peasants were never afflicted by serfdom, something that also influenced their mentality.6 In 1884, Yadrintsev, under the penname “The colonist”, published an article entitled “Correspondence between the colonies and the mother country” in the magazine “Eastern Review”. In the article, several characteristic features are noted that point to the similarity between Siberia and the agricultural colonies of European states. In Siberia, as in America or Australia, there was no aristocracy and there were no rigidly divided estates. People felt equal to one other. Like Yankees, Siberians were rude and uneducated, but had developed a sense of self-esteem. Siberia awakened the spirit of entrepreneurship in Russian people the way that America did in Europeans. As Russians began mixing with indigenous peoples, interethnic marriages took place, just as they did in the American colonies.7 Yadrintsev noted that, as a result, Siberian peasants had increasingly ceased to resemble their Russian counterparts.

Contemporaries often confirmed regionalists’ descriptions of Siberian identity. The well-known anarchist Pyotr Kropotkin recorded his impressions of Siberians in his diary in 1862, where he attested to “their feeling of superiority over the Russian peasant”.8 Kropotkin explained how Siberians spoke about Russia contemptuously, and how the word rasseysky (a corruption of the word for “Russian”) was even considered offensive. The Russian journalist and writer P. Suvorov, who came to serve in Siberia in the early 1870s, said: “This word ‘Russian’ […] has a deep, even political meaning. It is the idea of Russia as something distant, as having no kin or close relations.”9 More dramatic descriptions can be found in “Notes on Siberia” by the political exile Ivan Pryzhov, who wrote in 1882 that Russian people are absolutely wild in Siberia: “Siberian people are too often stupid and embittered, and take pleasure in bullying a visiting person or, as they called, rasseysky“.10

Anton Chekhov also described the Siberian spirit in great detail: “If you listen carefully for a long time, then, my God, how far removed life here is from Russia! […] While I was sailing down the Amur [River, east of Lake Baikal], I really felt I wasn’t in Russia at all, but somewhere in Patagonia or Texas. Quite apart from the strange, un-Russian scenery, I constantly got the impression that our Russian way of life is completely alien to the old settlers on the Amur. Pushkin and Gogol are hard to understand here, and have therefore never been a necessity, our history is boring and we immigrants from Russia are perceived like foreigners. If you want to bore a Siberian and make him yawn, then talk to him about Russian politics or the Russian government, or Russian art.”11

The central authorities also attended to features of Siberian consciousness. When in 1864 “a conspiracy of Siberian separatists seeking to wrest Siberia from Russia” was revealed, it was the first time in Russian history that the conspirators were not sent to Siberia. For Siberia was the conspirators’ homeland, that is, the homeland of Grigory Potanin, Nikolai Yadrintsev, Afanasy Shchapov, S.S. Shashkov et al. The interior minister wrote in this regard: “The goal of these criminal and senseless conspirators is to separate Siberia from Russia and to form some kind of federal republic, like the […] United States [of America].”12 Anatoly Koulomzin, chairman of the State Council, wrote in his memoirs of how he saw before his mind’s eye, as if in a nightmare, a scenario “in the more or less distant future, where the whole region on the other side of the Yenisei will inevitably become an independent separate state”.13 Irkutsk’s governor Alexander Goremykin excised every instance of the phrase “Siberia and Russia” in newspaper articles, replacing them with the words “Siberia and European Russia”; he also demanded that the phrase “the natives of Siberia” be used instead of “Siberians”.14 Goremykin treated “the natives of Siberia” considered to be separatists worse than any other political exiles. The royal court conservatives Mikhail Katkov and Konstantin Pobedonostsev repeatedly reminded Alexander III about the danger of separatist sentiments in Siberia.

As a result of the long struggle of Siberian regionalists for the region’s autonomy, the Siberian Republic was born in 1917. A group of Siberians convened an organizational meeting of the Union of Siberian regionalists in Petrograd on 5 March 1917. The then members of the Siberian Union of Independent Socialist-Federalists gathered in Novonikolaevsk (now Novosibirsk) on 11 March 1917. For the first time, the white-green flag of Autonomous Siberia was displayed in Tomsk on 1 May 1917. Later, the provisional Siberian government under the leadership of Peter Vologodsky signed the “Declaration on the state sovereignty of Siberia” in Omsk on 4 July 1918. However, the Siberian Union was dissolved on 3 November 1918 by Alexander Kolchak.

The Siberian movement in and around Novosibirsk, 2010-2014

The revival of ideas that comes close to this historical Siberian regionalism began in the late 2000s. It is important to bear in mind that this development was not rooted in the nomenklatura in any way, but generated by civic activists. Regional political leaders lost their independence after 2004, since which time, federal government began to appoint the heads of Russian regions. Russian governors finally turned into the mouthpieces of federal policy. Nonetheless, contemporary ideas of Siberian identity have been maturing discreetly in the local communities of Siberian cities.

Neo-regionalist tendencies are clearly visible in the example of Novosibirsk’s political landscape, where they increasingly provide a breeding ground for the city’s political forces. The first major rally under the slogan “Stop feeding Moscow!” was held in Novosibirsk in October 2011. The rally was attended by about a thousand people. The prominent Novosibirsk nationalist Rostislav Antonov, one of the rally’s organizers, said at a press conference that Siberia “is the main source of wealth of Russia, and yet it does not have enough money for basic necessities”. The disproportional distribution of resources means that Moscow takes everything from Siberia but gives nothing in return. Antonov said that Siberians do not need other people’s money, they can earn enough for themselves. Instead, he demanded a change in tax allocation mechanisms, so that a regional component would be incorporated into the tax on mineral extraction.15 Curiously, Novosibirsk’s city administration refused to agree to the rally being held and, at the end of the event, the organizers were penalized.

The rally coincided with discussions commencing in Novosibirsk’s blogosphere. After a few months, posters with slogans painted in the colours of the Siberian republic’s flag began to appear on the streets. Their appearance was first registered during the mass rallies “For fair elections” that took place in all Russia’s major cities, including Novosibirsk, between December 2011 and March 2012. The rallies were attended by all the opposition political forces in the city – liberals, nationalists and communists.

The rally “For fair elections”, Novosibirsk, February 2012.

Then, a commercial brand called “I’m Siberian” was developed in May 2012. The self-stated mission of the brand’s owners was to offer products with a “unique Siberian style” and “to promote Siberia around the world in its most up-to-date form”. Already on the first day of sales, hundreds of T-shirts, sweatshirts, passport covers and other products were sold under the brand “I’m Siberian”. The store “I’m Siberian”, which originated online and is headquartered in Novokuznetsk, already has several branches in Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Omsk, Barnaul, Mezhdurechensk, Norilsk and Irkutsk.

In 2012, the popular blogger Dmitry Margolin and the Novosibirsk artist Artyom Loskutov shot a documentary entitled “Oil for nothing”. In a brief description of the film, the creators state: “85 per cent of Russia’s reserves of lead and platinum, 80 per cent of its coal and molybdenum, 71 per cent of its nickel, 69 per cent of its copper, 44 per cent of its silver and 40 per cent of its gold are concentrated in Siberian territory. 50 per cent of the country’s total coal comes from the Kemerovo region. 90 per cent of Russia’s natural gas and 70 per cent of its oil are produced in Siberia. The federal centre gets the lion’s share of Russia’s budget, financed with the wealth and the labour of Siberia.”

At the same time, according to the film’s creators, the federal centre does not invest in Siberia’s development, so that the region retains the status of a colony. Above all, the filmmakers are worried about the lack of transport infrastructure in the region, which stretches over millions of square kilometres. Siberia would have the resources to build its own highways, were it not for the federal centre dispossessing it of these resources through exorbitant taxes. Popular local opinion leaders appear in the film as experts – Anatoly Lokot, mayor of Novosibirsk; Vladimir Suprun, assistant professor of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences; and Alexander Lozhkin, a Novosibirsk architect. They publicly accuse the federal government of pursuing a colonial approach.

In the spring of 2013, a scandalous exhibition entitled “The United States of Siberia” was held in Novosibirsk. The exhibition echoed the regionalist Potanin’s idea about Siberia’s affinity with the American spirit. Its organizers joked that if residents of Russia consider Vladivostok the Far East, then Siberians consider Moscow the Far West.

A little later, the flag of “The United States of Siberia” caused a national scandal. The main reason for this was a critical comment that Ivan Cherniavsky, a Siberian student of Russia’s Higher School of Economics (HSE), made on Twitter to Vladimir Solovyov, a popular Russian TV host. In response to which, Solovyov called Cherniavsky an enemy of Russia and a separatist, and later urged the authorities to conduct a thorough inspection of the Higher School of Economics. Symbols of the Siberian republic are increasingly beginning to appear on Novosibirsk streets, even in the traditionally apolitical Novosibirsk Monstration.16

One of the most vivid recent manifestations of the Siberian movement was “The March for the federalization of Siberia”, which should have taken place in Novosibirsk in August 2014. Novosibirsk members of the National Bolshevik Party organized the march, the name of which clearly resonated with the “federalization of Donbass” that the Russian authorities demanded at the time. However, the city and federal authorities opposed an attempt to hold this event, explaining their decision with reference to their desire “to ensure the inviolability of the constitutional order, territorial integrity and sovereignty of the Russian Federation”. However, the activists did not give up. They tried again to organize the march in favour of “the inviolability of the constitutional system and, in particular, of the state to protect the principle of federalism, enshrined in Articles 1 and 5 of the Constitution of the Russian Federation”. Nevertheless, the march was not permitted by the authorities even in this form.17 In addition, all the communities in social networks involved in organizing and coordinating the march were blocked at the request of Roscomnadzor.18 Roscomnadzor also issued official warnings regarding “appeals to participate in illegal activities” to fourteen mass media companies, for publishing information about the march for the federalization of Siberia. The media companies were forced to remove all information about the upcoming march.19 Among other things, on the day the march should have happened, all the main activists were detained by the police until the evening. As a result, the march created much ado, without ever having taken place.

The main features of contemporary Siberian neo-regionalism

So, what is the role of contemporary Siberian neo-regionalism in the cultural and political life of the region? And what’s in store for the Siberian movement? There are a few points worth considering.

1) The contemporary Siberian movement is a transpolitical movement that embraces Siberians with different political views. In recent years, the entire spectrum of opposition political forces in the region tried to actualize ideas of a Siberian neo-regionalism, from liberals to members of the National Bolshevik Party.

2) The central, underlying concern for contemporary neo-regionalism is Russia’s tax regime, and how this determines relations with the federal centre.

3) According to activists of Siberian neo-regionalism, Siberia supplies the rest of Russia. Siberians are well aware that the share of the federal budget spent on Moscow residents is on average between three and five times greater than that spent on residents of Siberian cities. A report by “Finance” magazine from 2008 received a lot of attention for stating that the government spends an annual average of 133,600 roubles on each Moscow resident, as compared with an annual average of 26,400 roubles on a resident of Novokuznetsk; 26,200 roubles on a resident of Krasnoyarsk; 23,700 roubles on a resident of Kemerovo; 21,700 roubles in Novosibirsk and 20,900 roubles in Irkutsk.20 In Novosibirsk, Siberians grew interested in how the gap between the budgetary provisions for Moscow residents and residents of Siberian cities changed over time. Further, research shows that there is a widespread belief that 60 per cent of the taxes collected in the regions are being sent to Moscow.21

4) Contemporary Siberian neo-regionalism is reviving an interest in the region’s history. Books by Nikolai Yadrintsev and other regionalists are being reprinted in large quantities. Yadrintsev’s foundational work “Siberia as a colony” was republished in 2003, with a print run of 5000. An influential group of scientists, researching regionalism’s heritage, urged the humanities departments of Novosibirsk State University and the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences to lobby for this publication. They continue to lobby for the publication of books by pre-revolutionary regionalists and regularly present research on regionalism in local humanities and scientific journals.

5) The “Siberian movement” has some support among officials. For instance, Viktor Tolokonsky, Presidential Representative to the Siberian Federal District, is well-known for his “pro-Siberian” remarks. After the 2010 census, Tolokonsky told reporters that people who chose to call themselves “Siberians”, far from constituting a sign of separatism, are actually demonstrating their sense of patriotism: “People who identify themselves as Siberians are rooted in this region, they see the beauty of Siberia”, he is quoted in the mass media as saying. “A man who sees the beauty of this land will never want to leave it.”22

However, in September 2010, just a few months before the census, Tolokonsky was prematurely removed from his post as governor of the Novosibirsk region, where he had served for ten years (before which, he had been Novosibirsk’s mayor), and immediately appointed to his current post of Presidential Representative to the Siberian Federal District. Formally, this could be considered a promotion but, in fact, the new position deprived him both of any real clout and of financial resources. In addition, the newly appointed governor of the Novosibirsk region Vasily Yurchenko had strained relations with Novosibirsk’s mayor Vladimir Gorodetsky, a close ally of Tolokonsky. Siberian neo-regionalists assumed that Tolokonsky was removed for being too independent, and the new governor was appointed exclusively for promoting federal policies in the region. But Siberian activists sympathized with Victor Tolokonsky.

6) The centres of neo-regionalism are large Siberian cities – Novosibirsk, Tomsk, Omsk, Irkutsk –, where the cultural life of the region is mainly concentrated; these are the places where the majority of Siberian intellectuals live. At the same time, residents of Siberia’s oil extraction and processing centres almost never participate in the promotion of the neo-regionalist agenda. For example, a visiting Moscow blogger Ilya Varlamov, intending to run for mayor of Omsk, immediately sensed the anti-Moscow sentiment and decided to use it. Varlamov called upon his supporters to “stop feeding Moscow and to give some food to Omsk” on his blog and then published a version of the infographic, quite popular by now among Siberians, about the budgetary output per Moscow resident, as compared with people from other parts of Russia, headlined in this instance “Moscow overeats, Omsk starves”.23

Since then, Omsk has repeatedly appeared in reports on neo-regionalism. Leaflets in support of the Novosibirsk march for “federalization” were actively disseminated there.24 In 2004, the political bloc “For my native Angara”25 received about seven per cent of votes and won two seats in the regional Irkutsk parliament. “We Siberians – pensioners and entrepreneurs, teachers and officers – have common enemies. They are the ones who export Siberian wealth abroad. They are the ones who do not pay taxes, who pollute our environment. Our Siberian land is great and plentiful. It is time to return the land to ourselves!” So said the bloc’s official statement.26 However, the most active neo-regionalists are the people of Novosibirsk. Perhaps this is due to the fact that Novosibirsk, as the capital of the Siberian Federal District, may well be the main potential beneficiary of the federalization of Siberia.

Prospects for the Siberian movement

The federal centre’s dominance over the distribution of power and financial flows is strongly resented in the Russian province. Anti-Moscow sentiments in Siberia are expressed in the form of neo-regionalism. Given the uneven and “unfair” distribution of oil revenue, a significant portion of Siberians feel left out. These sentiments are most widely held in the largest Siberian cities – Omsk, Novosibirsk and Irkutsk. A variety of opposition movements (and sometimes not only the opposition), have tried to draw upon such sentiments in order to score political points. For example, liberals, communists, nationalists and members of the National Bolshevik Party have participated in activities associated with the neo-regionalist agenda in Novosibirsk.

However, neo-regionalism can only take hold within the framework of the opposition agenda in the current political climate. Anatoly Lokot, the former State Duma deputy, a leader of the Communist Party and a prominent opposition figure in Novosibirsk, has spoken rather harshly of the federal centre’s policy, including in the commentary he provided for the film “Oil for nothing” in 2012. But when in 2014 Anatoly Lokot won the mayoral election in Novosibirsk, he was forced to rein in the “anti-Moscow” rhetoric. It was necessary to establish a constructive connection to the federal centre. After that, Anatoly Lokot banned the march “For the federalization of Siberia” in the city in August 2014. So the municipal and regional officials who have real power toe the federal line, a prerequisite for working effectively in the current context of the power vertical.

The theory of contemporary neo-regionalism is being developed by a variety of Siberian intellectuals – university intellectuals (Vladimir Shilovsky, Natalia Ablazhey), contemporary artists (Artyom Loskutov, Konstantin Eremenko), bloggers and publicists (Dmitry Margolin, Dmitry Verkhoturov). At the moment, neo-regionalists are not calling for the separation of Siberia from the Russian Federation, but are trying to draw the public’s attention to the uneven distribution of oil revenues.

Today, Siberian neo-regionalism is not a serious threat to the Russian Federation. It is rather a grassroots cultural phenomenon that is gaining popularity against the background of real anti-Moscow sentiment. However, activists have neither the political nor the financial leverage to influence those in power. The effect of their activities can only be measured in terms of media coverage. In some cases, politicians use “anti-Moscow rhetoric” during their political campaigns in the run up to parliamentary or local elections. After that though, their “neo-regionalism” instantly becomes a thing of the past.

See the Russian Statistics Service's data at Tayga.info, tayga.info/news/2011/12/20/~106368

Rossiyskaya Gazeta and Slon.ru on the ethnic composition of the population of Russia; see Demoscope Weekly, www.demoscope.ru/weekly/2011/0491/perep01.php

Zhigunova, M. "Siberian as a new nationality: Myth or reality?", Homeland 11 (2011): 45

"There are less Buryats than Yakuts, but more Buryats than Siberians", New Buryatia, www.newbur.ru/articles/5911

Yadrintsev, Nikolai, "Siberia as a colony in geographical, ethnographical and historical senses"; edition prepared by L. M. Goryushkin, M.V. Shilovsky and S.V. Kamyshan. Novosibirsk: Sib. chronograph, 2003, 110-22

Remnev A., "The western origins of Siberian regionalism", in "Russian emigration until 1917: A laboratory of liberal and revolutionary thought", St. Petersburg, 2006, 22

Ibid., 30

Remnev A., "A colony or part of the periphery? Siberia in the imperial discourse of the nineteenth century", in: "The Russian Empire: Stabilization strategy and the experience modernization", Voronezh, 2004, 16

Ibid., 18

Ibid., 18

Ibid., 21

Ibid., 88

Koulomzin, A., "Experience of a lifetime", Moscow, 2005, 19

Popov, I., "The forgotten pages of Irkutsk: An editor's notes", Irkutsk, 1989, 56

The rally "Stop feeding Moscow" was held in Novosibirsk; see newsland.com/news/detail/id/808392/

The "Monstration" is a mass action in the form of demonstrations with absurd slogans and banners that originally emerged in 2004 in Novosibirsk, and later spread all over the world as a form of contemporary art. From the beginning, Monstration participants were opposed to traditional political activities, saying that the time of politics is long gone. Monstration is held each year on 1 May and is now the most popular event in Novosibirsk. For example, the 2014 Monstration attracted about five thousand participants. The organizer of the event is traditionally the Novosibirsk artist Artyom Loskutov.

"Novosibirsk authorities refuse to permit march for the inviolability of the constitution", Tayga.info, tayga.info/news/2014/08/09/~117484

A federal executive body in Russia responsible for overseeing the media, including electronic media, and mass communications, information technology and telecommunications; and for ensuring compliance with the law protecting the confidentiality of personal data being processed; and for supervising the work of the radio-frequency service.

"BBC Russian Service amends its coverage of march for the federalization of Siberia, at the request of Roscomnadzor"; see www.newsru.com/russia/05aug2014/federalization.html

"The Muscovites' fortune: Twice as much spent per Muscovite than is spent per St. Petersburg resident", www.newsmsk.com/article/25aug2008/rich_moskvici.html

See: sib.fm/interviews/2012/06/26/obshhestvennye-finansy and, in particular, the following infographic: http://sib.fm/content/2012/baranova/g2.jpg

"Siberian nationality -- it's normal!", nsk.kp.ru/online/news/787471

"The organizers of the 'March for the federalization of Siberia' are wanted by police", tvrain.ru/articles/organizatorami_marsha_za_federalizatsiju_sibiri_zainteresovalas_politsija-374117/

A political bloc of people resident on the banks of the Angara River.

"Siberian separatism: Myth or reality?", www.novopol.ru/

Published 11 June 2015

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Transit © Stanislav Zakharkin / IWM / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTPublished in

In collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

For those who suffered the consequences of Yalta’s division of Europe, the Helsinki Final Act brought grounds for optimism. Today, as Russia’s regressive war on Ukraine reopens old conflicts, it stands as a monument to European modernity.

From Helsinki to full-scale invasion

Russia, European security and the OSCE

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and its denial of rights at home, are precisely the kind of development that the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe was set up to prevent. So why has the OSCE failed to fulfil its purpose?