The world that I see

lost its creed

sin speaks through the wicked hell

repossessed by those who burn

with the guilt of being born

The Haunted, “Downward Spiral”

On 1 November 1755, a powerful earthquake struck Portugal’s capital Lisbon, causing the death of 30 000 inhabitants and levelling large parts of the city. During its golden age at around the time of the Reformation, Lisbon had counted among Europe’s wealthiest and most distinguished cities. Though its prosperity had already begun to fade by the second half of the sixteenth century, its reputation as a cultural stronghold and significant mercantile centre lived on, along with the memory of grand voyages of discovery, trade with distant lands, and scientific progress. For that reason, the earthquake was an emotional blow to the European soul. The most advanced civilization was jolted from its certainty in continual progress and eternal prosperity.

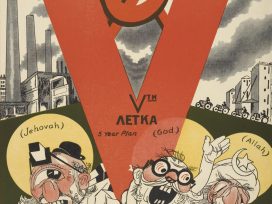

At that time, Europe had already seen many catastrophes which were, in terms of the number of deaths, significantly worse – one need only think of the Black Death. But the event in Lisbon opened up a whole new dimension of thought. Apparently, Europe had not suffered enough during the violent seventeenth century; now, the notion that God punishes sin and immorality began to lose its credibility. Even if such ideas lived on among the masses, it was no longer possible – halfway through the enlightened eighteenth century – to defend oneself entirely from the natural and amoral character of the event. Distressingly, the evolution of science, philosophy, and social theory had demanded that an event that at first glance looked like an evil caused by sin and impenitence instead be considered a product of chance and misfortune within a universe ruled strictly by law. The consequence of this was evil and pain that was objective, real – but also fundamentally manageable.

On 26 December 2004, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, India, Thailand, and Burma were struck by a series of powerful tidal waves caused by a large earthquake at sea, just off the island of Sumatra. Close to 300,000 people died and many cities and villages were destroyed completely. In the province of Aceh alone, on the northern coast of Sumatra, around 230 000 people perished, and the entire region was literally swept from the map. Some of the affected communities belonged to the world’s very poorest areas; it is no exaggeration to speak of completely incalculable consequences for their future development.

By now the world has seen many large-scale natural disasters; the tidal wave in southeast Asia is not entirely unique. Taking the increase of world population into account, for example, the 30 000 dead of Lisbon in 1775 is proportionately on the same order of magnitude as 300 000 dead in 2004. (In the middle of the eighteenth century there were an estimated 0.8 billion people on the planet; today there are more than six billion.) But in our time, natural disasters have yet another dimension. Despite our secular subconscious and our nearly absolutely empirical understanding of the processes – the patterns of shifts in the continental plates and the behaviour of water when those plates collide – it is impossible today to avoid the morally unsettling question of whether a natural disaster with such enormous consequences could also have struck the northern coasts of the Atlantic or Pacific and its wealthy industrial nations.

The answer seems to be “No, it could hardly have happened there.” The developed world in 2004 not only had sufficient knowledge and technology to understand and describe the details of the disaster’s course of events, but also could have reduced the impact of this apparent chance occurrence. What at first glance looked like a purely amoral, random, and natural event was gradually transformed into an occasion for painful insight into the moral depth and intensity of the world’s radical injustices.

The monumental event in Lisbon came as a shock to early Enlightenment rationalism that, despite resistance from the Church, had established a fundamental affinity between its own vision of the progress of reason and the Church’s authoritarian belief in revelation. Even though the Roman Catholic authorities had acted with great resolution against a series of new scientific and philosophical thinkers, there was throughout the seventeenth century and well into the eighteenth an unprecedented proximity between the Christian belief of the Church, and European universalism with its science, philosophy, and colonial politics. The rationalism represented by such prominent philosophers as Leibniz and Wolff was not fundamentally critical of the Church, but followed the Augustinian and Anselmian tradition of credo ut intelligam – an attempt to use reason in order to show that true reason finds expression in true belief.

In their respective territories, the different Christian confessions had issued one and the same guarantee: while it is true that this world is fallen and wretched, it is also bound for eternal salvation – if only the true faith is upheld. In certain regions, the Church held that human beings could themselves contribute to the fulfilment of that salvation, which creates a space for strong tensions between worldly and ecclesiastical claims to power. In other regions, the Church was more concerned that human beings should see themselves as passive recipients of God’s grace, a grace guaranteed by a church that was solely responsible for the legitimation of secular power. At the same time, throughout the Christian world the ideal prevailed that God, through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, had anticipated, in an actual, effective, and sufficient way, the final fulfilment of the real.

The dominant rationalistic philosophy was far from uncontroversial in ecclesiastical circles, but still I maintain that we can understand Leibniz’s “optimistic” premise – that suffering and evil are the prerequisites for being able to consider this world the best of all possible worlds – as a modern philosophical interpretation of the pre-modern social order, which is based on the assumption that those in power stand in close relation to a strong Christian Church. In a social order of that nature, the evil that befalls us is always ultimately seen as legitimated by God. Every aspect of society and life has to be considered in light of the universal salvation through Christ, which is unique to the Christian message. The church not only had an enormous influence on society; society itself was in certain ways a fully manifested corpus christianorum, a geographically materialized Christianity where everyone, regardless of position or personal preferences, lived within the framework of the eschatological blessing that was not shaken – but rather strengthened and confirmed – by continuous wars, tragedies, and deaths.

The earthquake in Lisbon thus came to symbolize a radical turning point in the history of modernity, not least of all a turning point for modern thought about the individual and society, which in the light of life’s enormous horrors took on a “humanistic” and “secular” gestalt. The image of God formed and distributed from the church’s pulpits gradually collapsed under the pressure of the questions raised by the Lisbon disaster. On the horizon there was even the threat of a collapse of the ecclesiastical system that had been driven to an acute need for a more consistent theological morality for its multifaceted exercise of power.

One could say that Enlightenment thought now entered a new phase, distinctly defined by Voltaire’s sharp attack of the contemporary Church’s perspective on humanity and its exercise of power. Deism, which earlier had usually functioned as an abstract and theoretical position, was now realized and embodied within the framework of an empirically-scientifically oriented perspective on society and humanism. When God was conceived as a distant and inactive God, human beings themselves had to act – for good or evil. For a philosopher like Voltaire, it was therefore not a question of a turn from theism to atheism; instead his conception of reality was based on the insight that the creator did not actively control all events – which in its turn implies that the Church could no longer be said to possess exclusive insight into the human situation.

This insight was coupled with the emerging empiricist thought that humans can only learn to understand and control their environment by confronting it directly and methodically, without reference to some divine inspiration. Religion recedes to make room for a constructivist view of society. In light of these circumstances, it is therefore no paradox when Voltaire’s criticism of the Church’s belief in revelation coincides with a criticism directed against Leibniz’ philosophically enlightened rationalism with its pared-down theology. According to the new and pragmatic Enlightenment, Leibniz’s thought only played yet another trump card for those in power, resulting in a vision of the human potential for action as crippled.

Leibniz’s rationalistic type of modernity – a pluralistic extension of Cartesian dualism – was thus cloaked in shame. Despite the fact that some of his concepts and theories would characterize all German Idealism from Wolff on, his system would be shelved until Hegel recycled it in his rigorous deconstruction of all modern distinctions.

What now began to develop instead with greater and greater strength was the empirical, encyclopaedic, technical, and pragmatic conception of reality in which the question of factual circumstances is placed at the centre. Evil and suffering were confronted – and called by their real names. There was a move away from traditional theology and its concomitant philosophical rationalism toward a modern secular humanism. When disaster strikes we must act in the service of good, not become deluded by a dreamlike and almost fanatic, irrelevant, and impotent brooding about whether evil itself attests to God’s goodness – that seems to have been the argument.

“I, an atheist, return to the church”– this surprising statement was in fact the headline for an appeal by Professor Emeritus Nils Elvander, published in Svenska Dagbladet in January of 2005. The background was the tidal wave disaster in Southeast Asia. Elvander motivates his return in following way:

I left the State Church for reasons of principle at the beginning of the 1950s. Ever since my youth I have been a convinced atheist, and I have no belief in eternal life. We have only this one life on earth, and it is for that reason that we must make the best we can of it. This also means helping those in need. But the strength of individual will must be multiplied in a constructively organized collaboration. The Swedish Church, with its organizational experience, its powerful contribution to our common cultural heritage, its rich fund of conviction and good will, and its ability to communicate a personal message to people in need, is a necessity now and will be for a long time. Archbishop K.G. Hammar found the right words about the need of those severely stricken to seek and find a glimmer of hope in these days of shock and despair. He did this on 30 December during a televised sermon from a church in southern Sweden, when he spoke in a simple and gentle yet also deep and clearly formulated way about the possibility of finding comfort in the midst of the blackest despair by reaching God in a silent search […] After the Church was separated from the state five years ago its membership has sunk at an increasing rate. If this trend continues, the Church will have severe economic problems: churches will close, congregations will be consolidated but will still dwindle in the long run, and the support of the state can no longer be counted upon. Just when the Church is most needed – it is shrinking. That is, unless those members who hold or held a negative position or those who are indifferent change their minds! We ought to now close ranks around the Church – even those of us who do not believe – and stay in the church or, as in my case, return to it. I hope and believe that many will share my opinion.

An atheist speaks of returning to the bosom of the Church. He is returning apparently despite the fact that for decades he has been convinced of the truth in such typical criticism raised against the Church and Christianity during the 1940s and 1950s by such eminences as Bertrand Russell, Jean-Paul Sartre, and – to stick closer to Elvander’s home of Uppsala – Ingemar Hedenius. And nothing indicates in fact that he has relinquished his fundamental atheism.

Elvander’s return to the church therefore traces an intellectual movement that almost seems a mirror image of Voltaire’s reaction to the earthquake in Lisbon. For the atheist professor Elvander, it becomes meaningful in the light of catastrophe to show his loyalty in the name of humanity to the ecclesiastical structure that the believer Voltaire, in light of a natural disaster, felt forced to leave because of its fundamental inhumanity and hypocrisy. For Elvander, the faith of the Church is an escape from the unbearable, while for Voltaire the Church’s theology becomes a reason to seek a radical humanism that attempts on its own to control and overcome the unbearable.

Perhaps it is simply the case that during the 250 years that have passed since the event in Lisbon, the Church has evolved from an authoritarian and powerful institution into a defender of humanity and good deeds. In that case, Elvander’s initiative would be completely understandable – a pure consequence of enlightened humanism and individualism which he in the end shares with Voltaire.

Taking that argument as a point of departure, one might say that Voltaire turned away from an inhumane institution with an inhumane dogma, from a church that had no power whatsoever to provide intellectual, political, or moral order to the catastrophe, while Elvander turns towards a humane institution, which of its own accord has resigned any claim to be able to explain the disaster dogmatically or morally, but which instead in a very practical way wishes to help people in need.

But doesn’t that argument falter? Why turn to the Church of all places? How can an atheist take such a step today, when faith has been undermined even more than it was during Voltaire’s time? Elvander’s argument is interesting for its complete incomprehensibility; the Church has “experience”, “cultural inheritance”, and therefore a kind of “humane” potential. This no longer comes into conflict with the humanism in Sweden that for at least fifty years has been synonymous with atheism. The real scope of the Church’s ability to act and its power are in fact threatened in our time, among other reasons because of the secularized Swedish unwillingness to acknowledge the potential of the Church for “good”. Elvander seems to be of the opinion that people today, against all reason, choose to leave the Church, thus weakening it when – in the eyes of this atheist – it has finally become meaningful and most needed.

The foundation of this reasoning seems to be a kind of atheist’s self-critique: today one ought, at least for the moment, to forget old theoretical anti-religion grudges and look ahead. Perhaps those atheist “cultural radicals” of the 1950s were a little too heated when they used to describe all theologians as intellectually dishonest? Leaving aside the question of whether this is a relevant backdrop for Elvander’s atheism, this type of perspective can in any case hint at why in this context he does not wish to discuss the Church’s remaining problem: God, and the belief that God interacts with human beings through the resurrected Christ. He does not even touch upon the classical question at the heart of critiques of religion, the question of which theological content, which perspective on humanity, and which claim to universality would be appropriate for the Church he is now returning to. The sharp criticism of Christianity that has been customary among Swedish atheists and humanists has been replaced by an extremely vague reference to Archbishop K.G. Hammar’s personal – and in Sweden often disputed – kind of relationship to Christian belief. This former critic of the State Church can therefore suddenly direct an unreserved criticism against all those who are indifferent to religion, an appeal to the feeling of responsibility that all of us ought to feel toward the Church.

Is it possible that ultimately, anti-religious humanism and contemporary church-based Christianity have to be imagined as two sides of the same coin? In that case, one might have expected Elvander to produce a call for an interpretation of the religious institution that resembled the late nineteenth century’s socially-oriented liberal theology, which in certain cases tended to transpose the Christian message entirely into terms of ethics and politics. But this clearly has not occurred to the professor.

His unexpected appeal seems in short not to be concerned with some simple humanism. The underlying incitement seems instead to be an unspoken doubt about the modern non-theological theories about individual freedom, knowledge, and morality. A deeper analysis of the tsunami disaster’s “real” issues is required here, an analysis which, according to this former critic of the church, can no longer be contained within the humanistic disciplines and philosophy, which were once considered capable of solving any problem.

Elvander points out that with his television appearance, the archbishop shows “what significance the Swedish Church can have in an hour of need in these times of dwindling Christianity, shrinking church attendance, and sinking membership after the Church’s separation from the state.” So this is not an argument for the Church to be used for purely social efforts; Elvander is demanding a religious intervention in humanism’s holy of holies, the individual soul: “There will also be a need for ‘caretaking of the soul’ in a broader sense and on a very large scale. Will the Church be able to meet this challenge?” Such a churchly function would scarcely be thinkable, and even less desirable, if one considers the issue from the perspective of modern secular humanism, in which the Church, in the spirit of Voltaire, has been criticized constantly for its tendency to suppress the potential of free humanity through its control of the spirit. But for Elvander, it now seems precisely this function of caring for the soul that once again makes the church an important actor.

How should we interpret this? In the aftermath of the great natural disaster of our time, even the rational and atheistic professor seems to demand that we admit that there are no truly rational answers, either scientific or moral. Now theology itself steps back onto the stage (even if Elvander does not mention theology he is in fact speaking indirectly about seeking God). Rather than exhibiting the traditional humanist spirit and directing his wrath against the God of the church and theology (who precisely through his supposed all-powerful nature reveals his total impotence) Elvander comes along – in his capacity as atheist – if not advocating, at least noting the possibility, of an inner religious healing through a “silent search” for the impotent God who does not bear responsibility for the tidal waves..

To be sure, the circle is not entirely closed. Elvander does not lead us directly back to Leibniz’s rationalism or to the pre-modern church structure with its definitive teachings about God, the world, and humanity. Nevertheless, we can again speak of the intimation of a flight from reality through the contemplation of the ultimate questions about reality, beyond those that are immediately practical and socially relevant. Even if Elvander also points out the Church’s potential as a practical assistance at the time of disaster, it is not this practical dimension of aid and social support that most clearly motivates his return to the Church. Elvander’s experience instead seems to have struck a dissonance with all the pragmatic perspectives that the atheists once defended; he is driven into a dialogue with an institution that wants nothing better than to convince people to consider reality as redeemed, despite all of reality’s incomprehensible fragility. The pragmatic principles of reason are put aside in the hope for a possible belief in the possibility of the impossible.

In line with his peculiar philosophy of nature, Theodor W. Adorno pointed out that the earthquake in Lisbon was enough to cure Voltaire of Leibniz’s theodicy. Yet Adorno believed that the earthquake was almost insignificant in comparison with the upheavals to society, that is, society’s natural disasters, which in some sense culminated in the German concentration camps.

Certainly, an earthquake that takes the lives of 30 000 people seems almost “human” and “neutral” if compared with a thoroughly planned and industrially staged extermination of millions of innocent people, and certainly Adorno is convincing when he suggests that the faith in an educated and socially conscious European humanism died in 1945, with the liberation of Auschwitz.

The problem with Adorno’s perspective is hardly his analysis of the successive failures of reason, the Enlightenment’s inner dialectic. What seems problematic in this context is instead the intellectual prescription he produces in the face of this collapse of humanity: a negative dialectic that “is neither pure method or anything real in a na�ve sense”, but which, in its deeply critical examination of the failure of reason, still refuses to let go of the ideal of reason as a utopian escape.

On the one hand, he therefore remains within the domains of secular humanism, but on the other he urges an absolutely negative escape, which could even be considered as radically theological and in that sense also radically non-humanist.. “He who believes in God can therefore not believe in God. The possibility represented by God’s name is upheld by those who do not believe.”

What seems to return in Adorno’s thought – though in a completely reversed register – is a form of philosophical rationalism. His dialectics contain a remnant of Leibniz’s optimism, according to which reason and belief in revelation worked in tandem with the aim of representing contemporary society as the best of all possible worlds. This remnant of rationalism, however, is expressed in strictly negative terms. In the spirit of Schopenhauer, Adorno conceives of the world and society as the least perfect of all possible worlds. So imperfect and broken is it, that true rationalistic reflection, like the belief in the God who creates every possibility for something better, has to be seen as a pure disciplina arcana, that is to say, a deeply hidden, other-worldly and secret insight. This is administered by those who, like the theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, maintain the strongest possible contempt for the worldly language that continually wants to profane and humanize the true mystery of salvation.

The consciousness of Auschwitz produces in Adorno’s theoretical perspective a radical despair about any concept of humanity as something good in and of itself, which in its turn prevents reason expressing anything positive about itself. Meanwhile, the basis for what is desirable is also denied in Adorno’s argument – that is, that which once formed the very basis of despair, the belief in the inherent value of humanity, every person’s right to life and freedom, along with the possibility of civilization. In and with Auschwitz and the interpretation of Auschwitz, every question of humanity finds concrete form in a banal personal question about the degree of guilt or innocence: “How do I exonerate myself?”

No one wants to take up the larger cultural context or see the total collapse as an anti-event immanent in culture. The Holocaust becomes an isolated, individual event, nothing more. Humanity and inhumanity merge, a petrification that results in a status quo of implacable relations. Europe’s understanding of itself is destroyed and we realize that there never was any real self-understanding. On the question of Germany, Sebastian Haffner comments on this confusion is an almost prophetic way, shortly before the outbreak of World War II, as if the war and the horror that was soon to come were merely a consequence of a natural connection: “[Germany’s] great paradox is that every act in this [its own] self-destruction consists in a victorious war.”

In light of Auschwitz, everything societal seems to have been transformed into a complex and entirely incalculable tangle of relations, which drive culture into its completely natural state, one regulated by its own laws that are completely unknown to humans – society as the opposite of tradition and culture.

The human contempt for – and simultaneous curiosity about – this unknown natural world finds expression in a mysterious theological question about that which is completely other. How can we get at the logic that can make this other, second nature comprehensible? Humanity will once again want to conquer nature, make it comprehensible, in order to be able to use it and exploit it for its own purposes. Perhaps we can achieve this, but in that case, how will we avoid ravaging and destroying nature in the manner of a revisionist historian like Faurisson?

Giorgio Agamben has attempted to define more sharply the question of the meaning of Auschwitz during our time. Can the natural status of the Holocaust – that is, the tendency of Auschwitz to transcend history and locate itself beyond our possible experience – be dissolved and ranged once again within a transvaluated understanding of culture? The horrors of the Holocaust always seem to be “greater than” something else. The truth about Auschwitz always stands out as “much more tragic, much more frightening”. With this in mind, Agamben asks: “more tragic, more frightening than what?”

No one can produce a believable image of Auschwitz, and therefore the ethics and politics of the future cannot be based on the idea that culture, in the name of humanity, has “enlisted” the Holocaust, mastering it, so to speak, for the purpose of prevention. The “other/second “nature’s disasters, to continue using Adorno’s concept, is obviously also more difficult for humans to predict, prevent, and control than the disasters of the “first” nature. It is for precisely this reason that the second nature seems so incalculably raw and untamable in comparison with the culturally defined first nature, which is shot through with the idea of mathematical laws – comprehensible codes that directly offer us the opportunity to incorporate nature with culture.

The impossible task of bearing “true” witness to the horrors of the gas chamber and the deep aporia that lies in the fact that the testimonies of survivors are our only possible points of connection to this incomprehensibility, leads Agamben to the general conclusion that our entire conception of historical knowledge is shaken by the encounter with the incomprehensible and inaccessible Holocaust. Paradoxically enough, it is in this case much more difficult to imagine a genuine cultural incorporation of the event – more difficult than comprehending the wrath of the tidal wave.

“The aporia of Auschwitz is in fact the aporia of historical knowledge: an incongruence between fact and truth, between verification and understanding.” In the Holocaust, nature breaks out in the form of the absolutely other, the non-spiritual, res extensa. History becomes the other, the second nature, and the problem of historical scholarship becomes the vain desire to achieve recourse to that second, absolute condition of nature, while the natural scientist only seeks nature in a relative sense, in the sense of a culturally comprehended nature.

From this, one would of course be able to conclude that the task of history is thoroughly impossible – while natural science achieves its effectiveness only through the power of its cultural conditions. Natural science is to that extent the humanism of our age: theologically disinterested and content with its own formulations. The study of history instead takes the form of a kind of theology, whose only possible credibility lies in its attempt to preserve a hope for something wholly other, something non-human, something that does not at base have a connection to the present human experience of guilt and despair.

The study of history – or the humanities in general – which in this situation continues with scholarly activities as if nothing had happened, becomes an involuntary part of a mendacious construction within that which is historically and culturally worthwhile is produced purely according to need. That which precedes and creates norms for historiography is not tradition and the good culture, but the fear of nature’s frightening magnificence. To call this history would be the same as accepting that we ourselves are always capable of reconstructing the unpleasant – an absolute idealism in the form of a cynical and ideological self-delusion.

Agamben realizes this, of course, and seems instead to want to forge a radical non-idealistic route, which in some respects is reminiscent of Adorno’s ambivalent oscillation between humanism and theology. When Agamben, despite all his reservations, still chooses to place the impossible testimonies from Auschwitz at the centre of the historian’s task (the impossibility derives from the idea that the testimonies cannot be fully adequate), he wants to point out the possibility of testifying to the fact that one cannot adequately testify: “The authority of the witness consists in his capacity to speak solely in the name of an incapacity to speak – that is, in his or her being a subject.”

In that way, one could argue, this exhaustion in the face of the task leads to a deeper historical consciousness that is not about remembering something bad as precisely as possible in order to avoid the badness and thus achieve future perfection. Instead it is about taking time for constant reflection so that testimony becomes an historical indication that history is impossible to capture, that tradition is impossible to describe, and that the cultivated life is impossible to live. In that way, perhaps, life could be lived a little more reflectively, without faith in its own inherent completeness.

In the traditional humanist view, all this looks like “obscurantism”. It seems impractical, unnecessary, and meaningless to deal with an idea about the historically true without simultaneously thinking that one has fundamental access to such a truth. It is not seldom that one hears the argument with the point of departure that it is not the study of history that should stand accused, but the metaphysical concepts of truth that place almost superstitious demands on the study of history. In the same spirit, reflection about the aporias of European scientific traditions are seen as a theoretical abstraction, without any concrete value for a science that aims for results. The only essential thing for the enlightened humanist is to moralize from the actual insight one has, as if it were absolutely true. Anything else would to undermine the belief in human possibilities.

The cultural value of avoiding a possible repetition of the Holocaust’s absolutely inhumane reality must, according to current humanism, be prioritized ahead of a deeper understanding of what this inhumane reality is. Using Voltaire’s terms, one can say that the Church’s teaching on original sin has to be abandoned in favour of a concrete human plan of action, according to which one successively excludes and hinders evil and painful consequences of nature’s fickleness – completely leaving aside all possible theological reveries about the metaphysical causes of evil and pain.

The question is whether in our time this self-important form of humanism really has begun to crumble. Can we take on Agamben’s perspective on the unfathomable? Are we really living in a post-humanist age? What would that mean for the humanities, which for such a long time have rested upon the view that cultural reality discloses itself to humanity in a meaningful way. Nils Elvander’s reaction is interesting not least because he, who represents an atheistic and demystified conception of reality, still feels forced to locate the most vital question of meaning in a religious sphere of “silent searching”.

He is driven to this by his reflection on the natural disaster of our age, the tidal waves in Southeast Asia, which then assumes the form of a radical cultural event. The poor countries were stricken terribly hard because their sea, the Indian Ocean, is not equipped with the warning systems that have long existed in the Pacific and Atlantic. After decades of historical attempts to contain and achieve disassociation from all of the perversity and inhumanity represented by Auschwitz, for example, thousands of people die as a direct or indirect consequence of the tourist industry’s exploitation of various coastal areas. But why was Elvander not driven to this silent search much earlier?

Let me make the following concluding sketch of my interpretation: if Lisbon paradoxically enough represents a turn that leads to an even more pragmatic belief in progress than the one contemporary thinkers wanted to repudiate, Auschwitz can be said to represent the absolute but invisible collapse of the belief in progress which despite the horror – or precisely because of its completely unfathomable form – escapes from the entire culture, becomes a parenthesis, stands out as something extraordinary, like a natural phenomenon, beyond the usual. It is only in the light of our age’s natural disaster, when we can once more see culture in all of its irreconcilable gestalt, that it slowly occurs to our time’s humanists and social scientists that humanism is not sufficient. Now they return to the church, while the natural scientists have taken over the academy.