The beginning of last year took many observers of the Czech media scene by surprise, when the owner of the largest agricultural and food processing conglomerate in the country, Andrej Babis (whose wealth is estimated by Forbes magazine at some 1.4 billion dollars), announced a rather ambitious plan to launch the regional news weekly 5+2 Days, which would be distributed freely in over seventy local variations. What stirred debate more than the generous scope of this publishing project, which currently employs around 160 journalists and has a combined circulation of one million copies, is the fact that Babis also heads the newly established political movement “ANO 2011” (Yes 2011), which aims to compete in the 2014 general elections. Although the movement is fueled by a strong anti-corruption rhetoric and a promise to improve political culture, the recent activities of its leader on the news media market – including a plan to buy the Internet news portal Aktualne.cz and to launch his own television channel – have sparked criticism, suggesting there is more to the business tycoon’s motives than pure “business interest,” as he has himself called it. After all, virtually the only advertisers in the new weekly have been his own companies.

Businessmen into media owners

Andrej Babis is not the only entrepreneur in the Visegrad region to have recently developed a taste for media. In fact, the last several years have witnessed a significant increase in this new type of media proprietor, with multiple business interests and profits largely made outside of the news media market.

In the Czech Republic alone, about a dozen news media outlets are currently in the hands of local businessmen. The financial daily Hospodárské noviny and the weeklies Respekt and Ekonom are all in the hands of the “coal baron” Zdenek Bakala. In addition, the owner of the largest media buying agency in the country, Jaromír Soukup, controls a media empire which includes several news and lifestyle magazines as well as the fourth largest television channel, TV Barrandov, recently purchased from another Czech industrial tycoon, Tomás Chrenek. In Slovakia, the investment giant J&T Group, co-founded by two of the richest Slovak financiers, Patrik Tkác and Ivan Jakabovic, controls the second largest commercial network TV JOJ and since 2009 – through one of their clients – allegedly runs the daily Pravda.

The portfolio of Ivan Kmotrík, the owner of the largest printing press and distribution company in Slovakia, includes the influential television news channel TA3. In Hungary, such a list would have to include the owner of the construction company Közgép, Lajos Simicska, who bought the street daily Metropol in 2011 from the Swedish-based Metro International. Another Hungarian business tycoon-become-media-proprietor, Gábor Széles, CEO of the Ikarus business group, owns the daily Magyar Hírlap and the cable television station Echo TV. Apart from the towering figure of Zygmunt Solorz-Zak, the second richest Pole, whose broadcasting and telecommunications empire Cyfrowy Polsat is still at the centre of his multiple business interests, Poland has been relatively immune to this particular type of media ownership, at least at the national level. However, this situation changed somewhat when 51 per cent of shares in Presspublica, the publisher of Rzeczpospolita, one of the leading national dailies, and other titles, were purchased in 2011 from the UK-based investment fund Mecom by Grzegorz Hajdarowicz, an entrepreneur with a history of investments in various branches of industry, including pharmaceuticals and film production.

The impact of the crisis: the departure of foreign investors

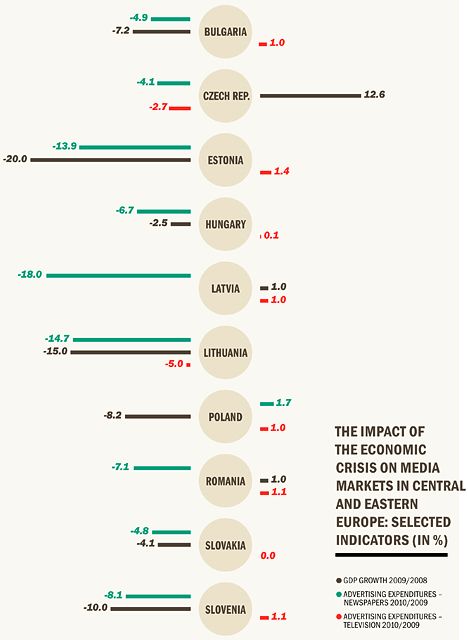

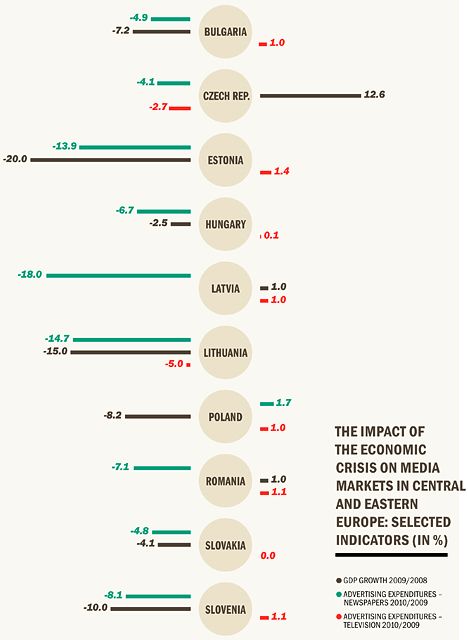

The aforementioned cases of local business elites buying stakes in news media outlets are part of broader changes on the map of media ownership in central and eastern Europe (CEE), which is generally characterized by a gradual exit of a number of western investors from the region. While the first signs of this departure could already be seen in 2006-2007 (especially with the withdrawal of Mecom from Lithuania and the exit of the Verlagsgruppe Handelsblatt from the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Bulgaria), the process has considerably intensified in response to the global economic crisis from 2008 onward. Apart from Poland, the only country in the EU to have avoided recession, all other CEE countries have experienced a considerable growth reversal (8 per cent on average in 2009), which has had a direct impact on the advertising sector, particularly in print media, which was already coping with a long-term decline in circulation. Among the V4 countries, Slovakia was most negatively affected, as the advertising expenditures in newspapers fell by 27 per cent in 2009, twice as much as in the Czech Republic. However, this was still not as dramatic as in the Baltic countries, where advertisers cut their newspaper expenditures by 44 per cent in Estonia and 58 per cent in Latvia.

The dwindling revenues have had consequences not just for the operating budgets of news media organizations, resulting in staff redundancies and salary cuts, but often for their ownership structures as well. Seeing their profits fall with little prospect for change, several publishers decided to sell either some or all their assets in the central and eastern European markets, including: Swedish Bonnier (former owner of the Latvian daily Diena, which lost 75 per cent of its advertising revenues in 2009); German WAZ (which pulled out of Romania, Bulgaria, and Serbia); Swiss Ringier (selling its papers in Romania); British Northcliffe International (owner of the Slovak daily Pravda until 2010); and Mecom (which left the Polish national daily market in 2011 with the aforementioned selling of Presspublica, although it continues to publish regional titles in Poland).

Unlike in the past, the buyers in all these cases were not other international companies, they were local businessmen willing to risk investing in a profit-losing market segment. All this means that while international players are still very visible in much of the central and eastern European media landscape, particularly in the Czech Republic, Estonia and Hungary, where they control up to 85 per cent of daily newspaper circulation and the majority of television audience shares, their regional presence has notably diminished over the course of the last four or five years. The outbreak of economic recession seems to have put an end to the long period of media internationalization, which had continued uninterrupted since the privatization of media markets in the early 1990s. We therefore may be observing a new phase in the development of CEE media systems, in which local ownership, particularly by local business elites, plays a much greater role.

Changing business models? From seeking profit to gaining influence

What are the consequences of this new model of proprietor for journalism and its ability to fulfill democratic functions, especially in the context of changing economic conditions? Acknowledging differences between individual media owners, evidence from across the region suggests that news media are often not purchased by local entrepreneurs in order to bring profit, but rather to gain influence and advance business and/or political goals. After numerous examples in Bulgaria, Romania and Latvia, it is regrettably the case that such instrumentalization of media by powerful oligarchs may no longer raise many eyebrows. However, it is perhaps more surprising that similar strategies of promoting and protecting political and business allies, while suppressing opponents or competitors, are used by media owners in central Europe. And this seems particularly true when such cases involve those closely affiliated with political parties or even those personally involved in politics. Shortly before the 2010 general elections in Slovakia, a reporter of the J&T-owned TV JOJ was suspended for preparing a critical report which revealed controversial financing behind the ruling party SMER. The editor of TV JOJ later admitted that he was given a direct order not to air the report by one of the J&T owners. At another private television station in Slovakia, the news channel TA3, belonging to the advertising mogul Ivan Kmotrík, journalists were instructed on which particular people and companies to accommodate or block in the news, depending on their personal and political alignments or whether they were advertising on the channel. The richest central European businessman, Petr Kellner of the Czech Republic, and owner of the investment company PPF, reportedly interfered on several occasions with the editorial policy of the business weekly Euro (before he sold it to his business partner Milan Procházka in 2011), ultimately leading to the departure of the editor-in-chief and a few other journalists, who later established their own online daily. Abrupt shifts in the editorial line are also not an unheard of consequence of newspaper buyouts in the region, as the case of Magyar Hírlap demonstrates, with its transformation from liberal to right-wing newspaper under its owner Gábor Széles, known himself to be a long-time supporter and sponsor of the governing Fidesz party.

An attempt to shift the editorial line – albeit in the opposite direction – has also been attributed to the new owner of Rzeczpospolita, Grzegorz Hajdarowicz. This issue came to particular prominence in his recent conflict with the editorial staff over a report about the alleged presence of TNT on board the presidential plane which crashed in Smolensk in 2010. The publication of this controversial story was followed by the firing of three journalists, including the deputy editor-in-chief.

However, even news media in the hands of businessmen who reportedly show more respect for editorial independence are not completely exempt from the negative effects of such ownership, as they might be prone to self-censorship when facing the challenge of writing about matters concerning their proprietor’s other interests. This problem is exemplified by the Czech weekly Respekt, an otherwise highly regarded investigative journal responsible for revealing many corruption scandals related to high politics and big business, which, according to one of its editors, has nevertheless taken a decision to keep away from the business affairs of its owner, the billionaire Zdenek Bakala. Their decision was made out of fear of not being trusted by their readers on this topic, regardless of the outcome of the investigations.

Searching for autonomy in uncertain times

There is no doubt that news media organizations in central Europe, print media in particular, are currently experiencing difficult times. Coping with the “double crisis” of declining circulation and economic recession, the impact of which still haunts most of the region, they are even less at liberty to choose their owners, and are therefore more likely to succumb to economic and political pressures (the two often going hand-in-hand in this region, especially through the distribution of state advertising). In the struggle for survival, structural autonomy from the domains of big business and politics – traditionally hailed as the normative prerequisites for free and independent journalism – appears to be too luxurious a commodity, and the media are increasingly facing the risk of involvement in the local political-economic networks and power structures to which their owners belong. It goes without saying that under such circumstances, their ability to perform the role of “watchdog” is constrained. In a pluralistic media environment, this might be less of a problem, providing there are still outlets which supply the public with unbiased information and conduct investigations independent from the interests of owners. However, we don’t have to go far to illustrate the consequences of a situation in which a large portion of the media market is concentrated in the hands of a businessman-turned-politician. The shadow of the former Italian prime minister is still very visible even from central Europe, where he is certainly not short of eager apprentices.