The lives and deaths of Georgi Markov

From being the literary darling of Bulgaria’s communist regime, Georgi Markov became its most vociferous critic. Yet his memory, in so far it exists at all, has been reduced to his spectacular assassination in London. On Markov’s work and the lives of the man behind it.

On 7 September 1978, while crossing Waterloo Bridge in London on his way to work at the BBC, the Bulgarian writer and journalist Georgi Markov was shot in the right leg with a 1.52-millimiter poisonous pellet by an undercover agent of Bulgaria’s intelligence services. He felt a slight sting and didn’t think much of it. But that evening, he began to show symptoms and his condition quickly deteriorated. Four days later, on 11 September, despite the efforts of British doctors, Markov suffered a cardiac arrest. He was forty-nine years old.

The Markov assassination became one of the most notorious of the era, a James Bond-style operation that the press dubbed ‘the umbrella murder’ (it was assumed at the time that the pellet had been shot via a modified umbrella, although this theory has since been doubted). It made headlines all over the world and remained in the news for months afterwards. Investigators and journalists alike began working feverishly to solve the mystery of the crime. Why would anybody kill a relatively unknown émigré in such blatant fashion? What had he been punished for? And who was Georgi Markov, anyway?

Before he left his native country for good in the summer of 1969, Markov had been one of Bulgaria’s most celebrated writers, the darling of readers and even some party officials. His fiction received major literary prizes and was adapted for cinema; his plays were staged in many of the big theatres in the capital, Sofia; and he co-wrote the script of the most popular Bulgarian TV drama series at the time, At Every Kilometer. For all of this, he was handsomely rewarded. Something of a bon vivant, he drove a silver BMW, took part in illegal high-stakes poker games, attended parties and lavish dinners with politicians, and even accompanied the country’s leader and de facto dictator, Todor Zhivkov, on country hikes. Yet he never lost sight of the many compromises he had to make as an officially recognized artist, and the self-censorship he was forced to carry out. ‘That was precisely the purpose behind the sweet life offered us – to stop us writing,’ he wrote.

Markov’s decision to abandon Bulgaria and throw away his entire career – fame, money, and privileges – was a product of his growing disgust with his own participation in the system and his frustration with the increasingly reactionary politics in Bulgaria after the crushing of the Prague Spring in August 1968. But he also had vague hopes of making it as an artist abroad, feeling that the provincial atmosphere in Sofia was too limiting for his talent and abilities.

‘I am indeed happy with the path I have chosen, however costly it may be’, Markov wrote to his Bulgarian ex-wife, Zdravka Lekova, in a letter from London. ‘I have not regretted my actions for a second and I do not miss the pseudo-literary life in Bulgaria, and my false happiness as a literary parvenu. The coming days may be difficult and impoverished, then again I might be lucky, but the most important thing for me is that I will write the works I want to write without taking anyone’s opinion into account.’

Nothing seemed to work at first. When Markov moved to London in the summer of 1970, after a brief stint in Italy, he had no money and no connections. He rented two rooms of a house in a dingy part of southwest London and, with no steady job and no knowledge of English, had to rely on the generosity of a few acquaintances. Unlike literary émigrés from the Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary or Czechoslovakia, who enjoyed at least some public attention and occasionally had access to university positions and translators, Bulgarians had practically no support networks. Of all the Soviet bloc countries, Bulgaria – the closest satellite of the USSR – was the least known and considered the least interesting. Markov stood little chance in his newly adopted country.

Yet he persevered. He quickly learned the language and eventually found a job as newscaster at the BBC’s Bulgarian service. He also began to contribute regular cultural and political pieces on Bulgaria – increasingly critical in tone – for Deutsche Welle, broadcasting on short wavelengths to audiences behind the Iron Curtain. But it was Markov’s series of personal narrative essays for Radio Free Europe, In Absentia Reports About Bulgaria, that put him directly in the line of fire of State Security (the feared intelligence service back home) and turned him into one of the most reviled and dangerous enemies of the regime.

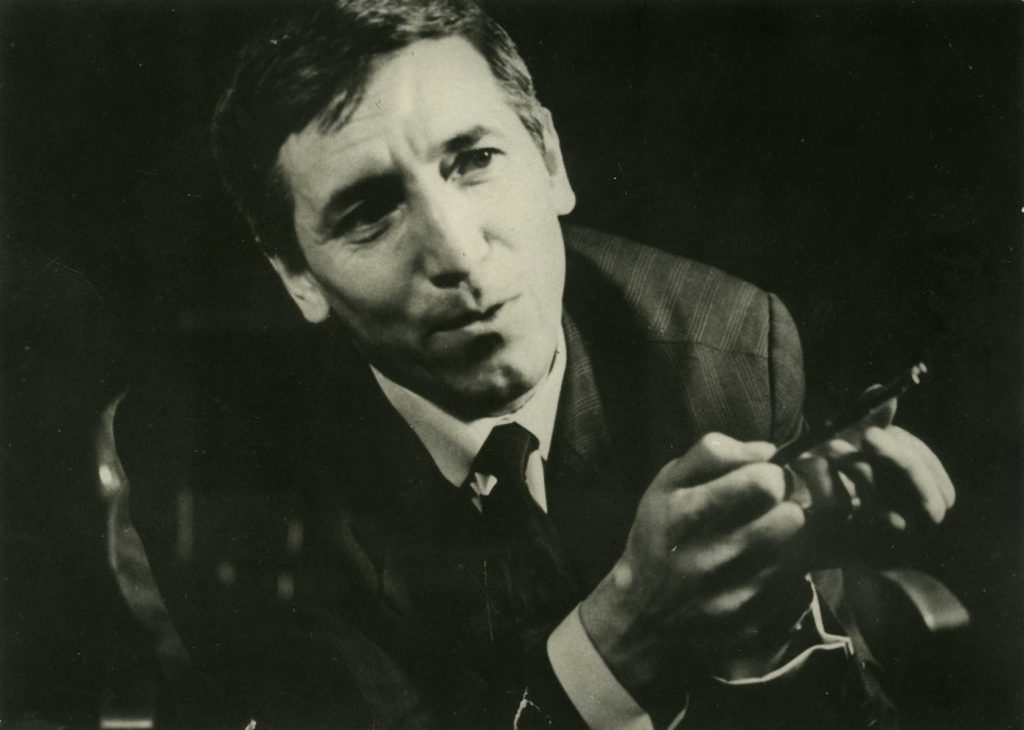

Georgi Markov in Berlin, 1967. Photo courtesy of Annabel Markova (family archive)

Critic of the everyday

Radio Free Europe was the most important US-sponsored broadcaster in Europe during the Cold War. Although it had been initially funded – covertly – by the CIA for propaganda purposes, evidence of the association was made public and the relationship ended in 1972. Through greater transparency in its operations, RFE gradually turned itself into the best alternative source of uncensored news and commentary for those behind the Iron Curtain, broadcasting in several languages, including Bulgarian. Sensing a threat to their monopoly on information, many socialist governments attempted to jam RFE’s frequencies or physically disable radio receivers from operating on short wavelengths. But these efforts proved futile. Millions of people across the Soviet bloc found ingenious ways to tune in to western broadcasts, and RFE was a particular favourite.

Socialist governments viewed all radio broadcasts coming from the West as conduits of ‘ideological sabotage’ – one of the worst possible crimes in their book. Markov’s indefatigable radio work was seen as particularly incendiary. In Absentia ran weekly from November 1975 to June 1978, with a total of 137 instalments, and quickly gained popularity in Bulgaria. Eloquent and engaging, written in the best tradition of narrative journalism, his essays offered an eclectic mix of personal memoir and overheard stories, vivid human portraits and entertaining anecdotes, popular history and philosophical speculation. He openly acknowledged his once privileged role in the system and exposed the secret lives of high officials and party functionaries, intellectuals and artists. However, he never forgot the people from ‘the lower depths’, those on the margins, to whom he devoted some of his most colourful writing: factory workers and university students, prostitutes and tramps. Politics aside, his writing often dealt with the everyday. He tackled such diverse topics as education, illness, sex, tourism, shopping and the fetish for western goods. In effect, Markov produced the most candid, incisive and comprehensive portrait of Bulgaria under communist-party rule, from the end of the Second World War until the late 1960s. ‘Why do the members of the Politburo not go to meetings on Thursdays?’ ran one Bulgarian joke in the late 1970s. ‘Because they listen to Georgi Markov on Radio Free Europe.’

The totalitarian era that Markov chronicled was different from Solzhenitsyn’s. Although Markov dedicated several essays to the ferocious Stalinist period in Bulgaria from 1944 to 1956 (which he’d witnessed as a teenager and student), with its forced collectivization, mass executions, arbitrary violence and attendant fear, his main focus fell on the subsequent period of liberalized politics from 1956 to 1968, when the regime’s power and very existence no longer relied on unrestrained physical terror, but instead functioned much more subtly through a widespread, ubiquitous form of social and material corruption. Bulgaria’s was a humdrum, pedestrian totalitarianism that was never disrupted by great traumatic events or upheavals: there was no social disorder comparable to that in Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968, or Poland in 1968 and 1980. If anything, the absence of organized dissident movements was itself a symptom of the social corrosion.

The corruption and nepotism that plagued all spheres of life, the attempt to control intellectuals and the populace through a feudal system of privileges based on ideological subservience or personal connections – one where individual worth and talent had little to do with social advancement – created what was perhaps the regime’s gravest crime: the manufacture of mediocrity. It was a recurring theme of In Absentia Reports: ‘The most distinctive feature of the socialist careerist, no matter whether in industry, culture, or administration, is his mediocrity.’ Elsewhere, Markov talked about Communist Party functionaries as ‘fat men with lumbering brains and bad manners, who live the lives of Gogolian governors in an obscure Russian province.’ Bulgaria’s leader, Todor Zhivkov, was the quintessential functionary: ‘a not too intelligent young dictator … with the aesthetic faculties of a sergeant major.’ Though acerbic at times, Markov’s portrait of Zhivkov is stunningly objective. He recognized Zhivkov’s strong qualities, his ‘undoubted natural intelligence, quick wit and a magnificent memory’, but ultimately saw in him a mediocre person, no different than ‘the local postmaster, or the teacher in the preparatory school, or perhaps one of the council clerks or the local agricultural expert’ who had mistakenly been given the leadership of an entire country.

But mediocrity was a characteristic not just of party bureaucrats. Faced with arbitrary conditions, artificial norms of production demanded by the Soviet-style command economy, comprehensive low pay, and the negative example of an incompetent party elite openly skimming off the state, ordinary Bulgarians were only too quick to learn the lessons. ‘The corruption of labour was a consequence of the moral corruption fostered by the highest leadership,’ Markov concluded. Doing work was generally considered drudgery, a sign of low status, where quality and efficiency had little place. One result was that graft became widespread, as public property was seen as nobody’s property, and nearly everyone – from the highest official to the lowest menial worker – attempted to extract private benefits from their respective stations, often using ideology as a cover. Talk of socialism aside, Bulgaria’s was a profoundly materialistic society, one in which consumption and the cult of the commodity – especially the scarce, western-produced commodity – took precedence over everything else. ‘I don’t know of another society with better pronounced petty-bourgeois character than that of the ruling Communist Party,’ Markov wrote.

In his radio essays on RFE, Markov also dedicated substantial space to Bulgaria’s cultural life, a topic he knew intimately. Writers were ‘the officially sanctioned fabricators of the regime’, who dressed totalitarianism in a cloak of respectability. As a result, art was replaced by pseudo-art, work by pseudo-work, as with every other sphere of human endeavour in Bulgaria. It was a world of appearances, where meaningless, ritualized language overlay the most ordinary phenomena – a lie people often recognized as such, but which they accepted nonetheless. The construction of totalitarian reality was the national stagecraft, a willing suspension of disbelief. In an essay about official parades in Sofia, Markov described how, among the banners and portraits of communist leaders, a group of leather workers shouted the ludicrous slogan ‘More and mo-re skins for the Pa-a-rty!’ Like Vaclav Havel’s famous depiction of a greengrocer who hangs a sign in his shop window proclaiming ‘Workers of the World Unite!’ for no other reason than to demonstrate his outward loyalty to the system, the Bulgarian leather workers – and everyone else, including writers – took care to affirm their Marxist credentials without investing in the underlying ideology. As Havel observed: ‘Individuals need not believe all these mystifications, but they must behave as though they did … They need not accept the lie. It is enough for them to have accepted their life with it and in it. For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system, fulfil the system, make the system, are the system.’

Although Markov had always prided himself on being a critic of the regime, and for a time had naively believed that he could contribute to its reformation, he recognized that ultimately he had to choose between the artist and his evil double, the propagandist. ‘If you ever had an idea about the person you were, if you thought one thing, while you discovered that slowly and inexorably you were turning into something quite different, there probably comes a time, when you wish to break either the mirror or your own head,’ he wrote at the end of In Absentia Reports, describing his reasons for leaving Bulgaria. ‘I cannot claim that mine was a case of political courage or integrity; it was merely a matter of my own sense of the unbearable.’

It may seem a strange today, even unbelievable, that a person could be killed for telling such ordinary stories; that a relatively stable political system would employ its entire repressive apparatus, manpower and financial resources in order to eliminate one voice talking over the radio. Georgi Markov described neither the violence of the concentration camps nor any demonic murderous spree. But by exposing the regime’s ideological fraudulence and moral hypocrisy, by showing its pedestrian, everyday character, the banality of its evil, he undermined the grand project of mythmaking that every political system relies on for its legitimacy and survival.

As early as 1971, State Security had opened a file on Markov code-named ‘Wanderer’, but as time passed and his writing became more seditious, the regime in Sofia turned more aggressive. Because Markov had often insisted that reformation and the eventual change of the Bulgarian regime could only originate with the ruling elite, State Security was concerned that his broadcasts could lay the critical groundwork for dissidence within the Bulgarian intelligentsia. Critics of the regime gained some protections in 1975 when many Soviet satellites – including Bulgaria – signed the Helsinki Accords, which besides guaranteeing the territorial integrity of states also included safeguards of basic human rights and freedom of thought. The accords were not a treaty and therefore not binding on the signatories, but their language about human rights and freedom of conscience was embraced by East European dissidents fighting their oppressive governments, which reacted with ever more devious ways of crushing resistance.

The Soviet Union had decided to rid itself of recalcitrant writers like Joseph Brodsky and Alexander Solzhenitsyn by expelling them from the country (in 1972 and 1974, respectively). Bulgaria had no such option: Markov was already abroad, out of reach and out of control, and could neither be bought nor imprisoned. For a small state like Bulgaria, he was becoming a huge political liability.

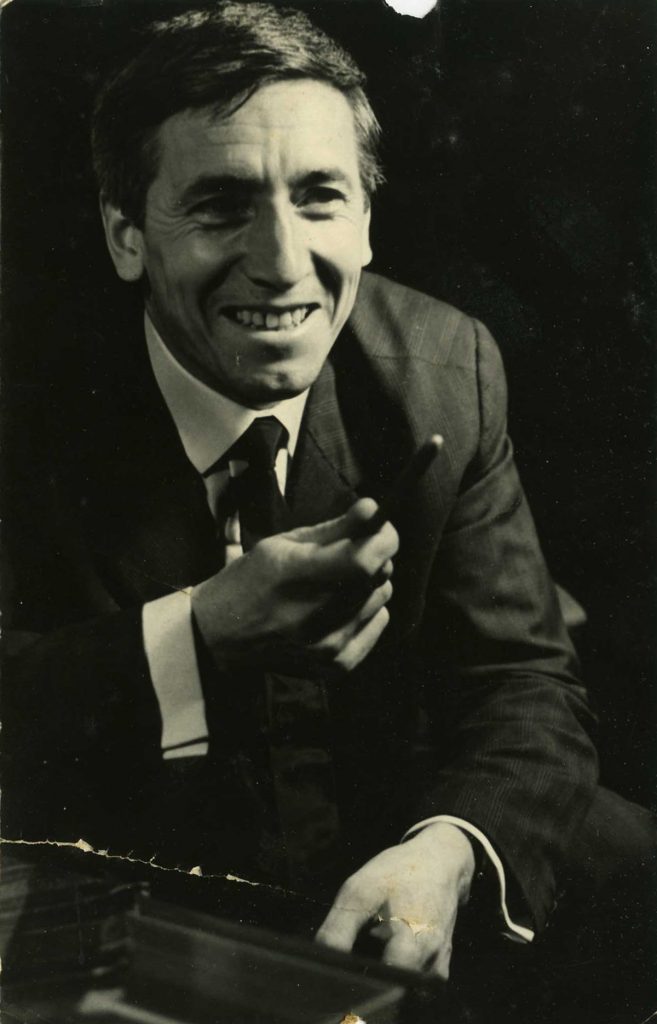

Georgi Markov in Berlin, 1967. Photo: courtesy of Annabel Markova (family archive)

Markov’s second murder

Despite the overwhelming evidence, hard and circumstantial, that has come to light about Markov’s assassination, speculation about his role as a political dissident and artist still proliferate. Opinions are sharply split, and not always along political lines, with one side accusing Markov of being a traitor or a suave servant of the regime, and the other lauding him as a national hero and a defender of the values of truth and freedom. Markov’s two lives – first as a member of the official intelligentsia, and later as its vociferous critic in exile – naturally fuel such divisions, but they also point to the nature of the regime. Markov’s biography stands witness to a system that artfully blurred the lines between ideological demands and individual desire, making self-deception appear as a natural choice. Perhaps Markov’s greatest feat was to expose the difference between the two.

Most importantly, however, the debate surrounding his legacy reveals the ambiguous national attitude toward the historical legacy of Bulgaria’s totalitarian regime as a whole. As Tony Judt wrote in Postwar: ‘the Cold War fault-line fell not so much between East and West as within Eastern and Western Europe alike … Between those for whom Communism brought practical social advantage in one form or another, and those for whom it meant discrimination, disappointment and repression.’ The ultimate insider as well as the ultimate outsider, Markov showed that the division ran right through him.

Certainly, as he so often observed in In Absentia Reports, a substantial stratum of the Bulgarian population received material benefits and social privileges from the communist system, provided they were willing to dispense with their basic rights and abstain from open criticism. For the average citizen of Bulgaria, life was, if not satisfactory, then calm and uneventful, a dutiful trudge along prescribed lines. For many others, though, it was the exact opposite: full of physical and psychological violence, persecution and daily cruelties.

But while a national consensus about the communist past may be difficult to achieve, Bulgaria’s post-communist governments have been guilty of actively suppressing the memory and examination of the crimes of the past. As in many other countries across the former Soviet bloc, the political changes in Bulgaria in 1989 were initiated on the inside, by members of the Communist Party and State Security, who often used their positions to derive the best personal advantage for themselves, their relatives and their friends. Political rule was simply transformed into private economic power, as public property was quickly – and most often criminally – privatized by people who had direct or indirect links to the old communist regime. And controlling the present, as Orwell knew so well, means controlling the past and, more importantly, the future.

‘In Bulgaria, there was no real decommunization, no lustration, and the State Security secret files were opened very late so as to achieve this controlled transition to democracy,’ says Hristo Hristov, a Bulgarian journalist who has written a seminal book about Markov’s case. ‘But in the final run, society is still manipulated by the sa me mechanism, in which former members of the State Security are always present – in politics, in the economy, in the media. It is the reason why we don’t have a memory of Georgi Markov. And the memory of Markov is missing because there is no memory of the victims of communism as a whole.’1

A 2013 a study spearheaded by the Hannah Arendt Center in Sofia examined young Bulgarians’ knowledge of totalitarianism in Europe and at home. The respondents were between the ages of 15 and 35, and the results were striking: 79 percent hadn’t heard of the Gulag; 67 percent hadn’t heard of the Iron Curtain; 51 percent didn’t know the reason for Markov’s death; and 89 percent had no knowledge of the book In Absentia Reports.

But the Bulgarian crisis of historical memory is hardly peculiar to young people, especially when it comes to Markov’s literary works. Most adults are familiar with his name today, but only in the context of his murder. Few have read his essays or novels. The Bulgarian who should have taken the same position in his nation’s literature and political history as Brodsky in Russia, Havel in the Czech Republic and Milosz in Poland has been relegated to the dustbin of memory. After his murder abroad, Markov was killed a second time, in his home country.

Markov’s fate outside Bulgaria has not been much different. Some foreigners still recognize references to ‘the umbrella murder’, but his writing is virtually unknown. A heavily abridged version of In Absentia Reports came out in Britain in 1983 and then a year later in the United States under the title The Truth That Killed, but the book has long been out of print. Reviewing it for the Los Angeles Times, the social historian Arthur Weinberg wrote: ‘What George Orwell imagined in ‘1984’ about a totalitarian society, Markov makes real in his memoirs of life in Bulgaria under Bolshevik rule: terror, tension, oppression.’ The occasional superlative in the press aside, The Columbia Literary History of Eastern Europe Since 1945 does not even mention his name.

‘The umbrella’ seems to have been an effective ruse after all, for it managed to conceal the victim underneath. It has created a cultural cliché, which has overshadowed the complexity and contradictions of both Markov’s character and his times. But it is in the interstices of history, in the messiness of personal emotions and motivations, in the twists and turns of the everyday (which Markov himself was so interested in) where we can discover a deeper kind of truth, more subjective and ambiguous perhaps, but more authentic. In order to understand who Georgi Markov was, and what the Cold War meant, we have to look first into the very warm human heart.

This is an extended version of an article first published in the IWMpost Fall/Winter 2021. Additional sections were first published in The Nation on 18 March 2014.

Interview with the author.

Published 20 December 2021

Original in English

First published by IWMpost / The Nation / Eurozine

Contributed by IWM © Dimiter Kenarov / IWMpost / The Nation / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

In socialist Czechoslovakia, one of the world’s biggest arms exporters, issues of durability and demise were taken into account. Why, then, do Cold War weapons continue to resurface in deadly attacks and armed conflicts across the globe, well beyond their alleged obsolescence?

When Boris Yeltsin told George Bush in 1991 that the USSR couldn’t exist without Ukraine, he wasn’t referring to the economy: culturally, Russia would have been isolated. Today, the same thesis about Slavic identity is being debated with rockets. Serhii Plokhy on Ukraine’s special role in Soviet and post-Soviet history.