Russia is not the sea

Imperial Russia saw the nation as the sea into which all the other Slavic cultures flowed. The idea persists today not only in Russia’s attitude towards its neighbourhood, but also in the way eastern Europe is studied in the West.

‘Will the Slavic streams flow into the Russian sea? Or will it dry out? This is the question,’ wrote Alexander Pushkin in 1831. The line is from ‘To the Slanderers of Russia’, a triumphal ‘ode’ to Russia’s crushing of the Polish uprising of 1830–1831. The poem is a defiant statement of a tenet of Russian geopolitical thinking that continues to dominate the way Russians – both politicians and ordinary people – view their country’s role in the lands that border it to the west: that of natural hegemon whose right to rule is based on the natural ‘fraternity’ of Slavic nations, whose resources (cultural or otherwise) must be channelled towards the imperial centre.

Pushkin refers in the poem to the bloody suppression of the Polish uprising as a ‘family quarrel’. The same ideas underpin Russia’s war against Ukraine. Putin is particularly fond of the ‘brotherly nations’ motif and made a point of underlining it in his recent visit to Alaska to meet Donald Trump. Yet such a view is not the preserve of aggressive militarists like Putin: leading oppositionists such as Aleksei Navalny or, more recently, Vladimir Kara-Murza have also used the ‘brotherly nations’ rhetoric.1

The image at the heart of Pushkin’s poem posits an essential unity of Slavs that centres on Russia. The target of the poem’s polemic was, of course, Poland, which only decades previously had been a formidable force in east-central Europe and a major geopolitical rival of Russia. Poland, in Russian thinking, was a treacherous member of the Slavic family that had sold itself to the Catholic Latin west, but which could be ‘persuaded’ that its natural allegiance should be to Russia.

But Russia’s oceanic capacity goes well beyond Poland. It encompasses the whole Slavic world and more. As Putin likes to say, Russia’s borders have no end. According to this view, the nations to the west of Russia, which mainly speak Slavic languages, are merely ‘streams’ that must ‘flow into’ Russia so that the latter does not ‘dry up’. In other words, imperial dominance over neighbouring lands and peoples is a precondition for Russia’s existence.

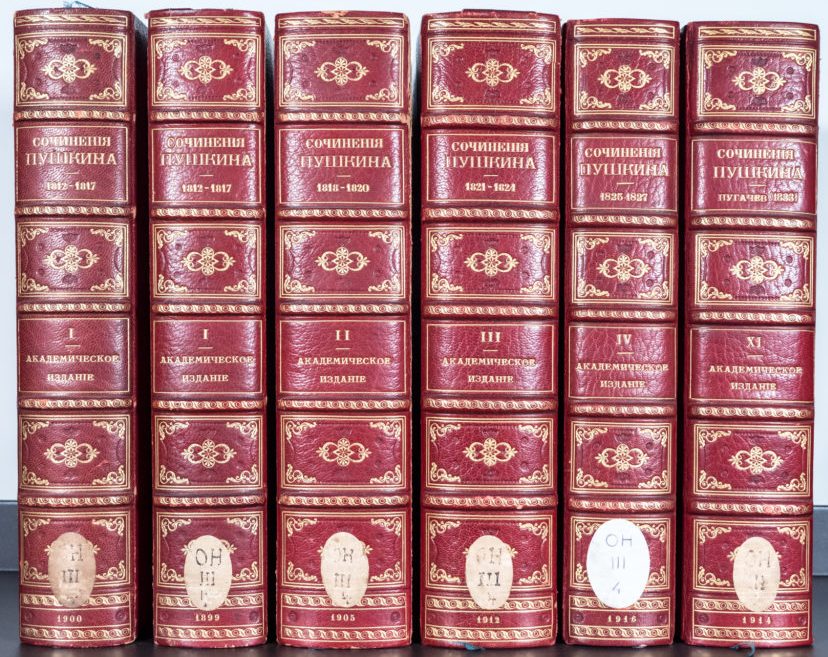

Pushkin’s Complete Works, 1905. Image M. Ruscio / Source: Wikimedia Commons

‘To the Slanderers of Russia’ was one of Pushkin’s most widely read and influential works in its day, and one of which he was immensely proud. Today, too, it is frequently cited in Russian public discourse. Yet it is oddly neglected in western Pushkin studies, due to the discomfort caused by its imperialistic jingoism. Many western students of Russian will never come across this crucial part of the national poet’s oeuvre, nor understand quite how central the ideas it expresses have been to Russian geopolitical thinking for the past two centuries.

The imperial reflex

The idea of Russia’s imperial sea might not be central to the western Russian literature syllabus, but it does manifest itself in other ways: it is fundamental to how knowledge about Russia and east-central Europe is structured in academia and beyond.

If one studies eastern European languages such as Polish, Czech or Ukrainian at a western university, one will usually do so as part of a Russian studies programme. These ‘smaller’ languages are generally offered as a supplement to the study of Russian, sometimes in the context of ‘Slavic’ or ‘Slavonic’ studies. These language options will not necessarily be closed off to students of other subjects, but they will be intended mainly for those studying Russia and will be institutionally bound to Russian studies. The fact that they may not be offered to degree level in the same way as Russian reflects this supplementary status.

The pattern is not restricted to language study. It applies across disciplines from literature and history to political science and economics. Political science programmes focused on Russia will often, for example, teach the politics of ‘Eastern Europe’ or ‘Eurasia’ in terms of their relationships with Russia, rather than in their own right. One only need look at the names of programmes to see that these regions are viewed as peripheries from which so many political, cultural, economic streams flow into the understanding of the central object of interest: Russia.

Formulations like ‘Russian and Eastern European’ or ‘Russian and Eurasian’ append individual courses, BA and MA programmes, monographs and textbooks, research centres and whole institutions. ‘Russia’ is placed at the centre, and the ‘tributary’ nations/cultures/languages are grouped together under a regional designation that essentially mirrors the history of those places’ imperial subjugation.

This is not to say that all those who run and teach those programmes (for better or worse, I am one of them) share the view of natural Russian hegemony over this broad river basin. The structures of knowledge production are often of an inadvertent acquiescence to real-world power hierarchies and the result of years of institutional bias and inertia, rather than a direct reflection of worldview. The loud and the powerful attract attention, and money flows to those who purport to understand the world’s important players. The vast swathes of the earth that lie in the flood plain of these unpredictable geopolitical rivers are less worthy of our attention. They often sink unnoticed under the flood.

I studied on an MA in Russian and East European Literature and Culture at University College London’s School of Slavonic and East European Studies. I took only one module on Russia (the others were on Poland and translation studies, and my dissertation was on Ukraine). I could have taken no courses on Russia at all, yet Russia would still be named on my MA certificate. Today, I teach on that same programme; I have registered my dissatisfaction with the situation more than once, and I hope, alongside like-minded colleagues, to change it.2

The structures described above become even more questionable compared with the study of other large European countries. We do not find the formulation ‘German and Central European’ in the name of programmes and centres across the English-speaking world, despite the historically dominant, and often aggressive role of Germany in this region. Admittedly, colonial pasts do, now, often shape the way we study the culture, history, politics of former imperial European powers. Students of French may well learn about Algeria or Senegal, for example, in relation to France; they may study the colonial history and the postcolonial Francophone writing of these places, and so on.

There is a crucial difference, however, between this and the way Russia is taught: students and scholars will encounter the relations between France and its former colonies through a predominantly postcolonial (or decolonial) approach. The idea of applying post- and decolonial thinking to Russia has existed for some time, for sure, but it is nowhere near as central and well-developed as it is in the study of other former European empires. If it were, Russian literature courses would place Pushkin’s ‘Slanderers of Russia’ front and centre, not somewhere hidden away in the footnotes.

Watery geopolitical metaphors were not the preserve of Pushkin. His Ukrainian counterpart, Taras Shevchenko, also used them. In Shevchenko’s poem ‘The Dream,’ the unnamed narrator encounters, by the riverside monument to Peter I in St Petersburg, the ghost of a Cossack, who laments:

But my heart is sad

To hover above Neva!

Ukraina, far away,

Perhaps does not exist…

I would fly and gaze on her,

But God will not permit.

Maybe Moscow burned her down,

And drained away the Dnipro

Into the blue sea.3

For Shevchenko, the great Ukrainian river draining into the Russian sea is not a matter of natural mutual enrichment, but of man-made extinction. And this is not the only echo of Pushkin in Shevchenko’s work. His ‘The Caucasus’ is a savage satire on Russian imperial hubris in the region that is the setting for Pushkin’s ‘Prisoner of the Caucasus’. Shevchenko’s poem encapsulates Russian ideas of ‘fraternity’: ‘From the Moldovan to the Finn/Silence is kept in every tongue’. There is an echo here of Pushkin’s threat to the West that, if it challenges Russia, then ‘from Perm to Tauris’ fountains/From the hot Colchian steppes to Finland’s icy mountains’ the Russian soldiers will rise.

Pushkin’s 1831 poem was important to his successful rehabilitation with the Tsar after his youthful dalliances with progressive politics. It helped secure him wealth and status and cemented his legacy among patriotic Russians. Shevchenko’s political satires, circulating only in manuscript among trusted friends, were used to sentence him to ten years forced military service thousands of miles away in today’s Russian-Kazakh borderlands, with a prohibition on writing and painting.

These poems’ call to return the voice to the voiceless in the imperial encounter feel far more in tune with the decolonizing spirit of the humanities today. Indeed, the simple act of reading them next to Pushkin’s ‘Slanderers…’ can help break the imperial bind that constricts not only the study of the nations that had the misfortune to exist next to Russia, but also of Russia itself. Yet this is almost never done in our classrooms.

Towards a new ecology of knowledge

How could the structural voicelessness of the cultures subjugated by Russia to be confronted institutionally? Certainly, one important step would be to root out the Pushkinian modes of thinking from how we structure our knowledge of the world. We must stop thinking of Russia as a sea into which the study of ‘peripheral’ cultures and countries should flow. In order to rectify historical imbalances we should exercise ‘positive discrimination’ and give these cultures extra space in our programmes. If we don’t acknowledge the violent inequality of the imperial encounter, or the legacy of invisibility that it brings to the colonized, how can we claim to truly understand it?

Can the structures and institutions of ‘Slavic studies’ or ‘Russian/East European/Eurasian’ area studies rise to this challenge? Here I turn to the central problem with Pushkin’s aquatic metaphor: it ascribes a natural inevitability to a very artificial, engineered situation. The streams of Slavic cultures (or, indeed, non-Slavic – one might find the Hungarian, Romanian or Baltic languages caught up in all this) do not naturally flow into the Russian sea. Rather, they were redirected towards that sea by a brutal process of engineering – the digging of canals, the building of dams, by catastrophic floodings and drainings. We know from Kakhovka that a dam can be built in the service of an empire’s economic development, and then bombed, and an ecocide engineered, in the service of that same empire. None of it, neither the construction nor the destruction, is natural, and none of it can easily be undone. The same goes for the ways in which we have channelled and reservoired knowledge.

A good first step in addressing these problems would be to start globally. Like environmental issues, issues of knowledge production are not isolated and self-contained: what we do in our classrooms spills out into media discourse, policy making and public perceptions. Institutions that are built around the idea of ‘Russia and Eastern Europe’, or even Slavic Studies, are something akin to the fossil fuel industries. If we want to find a sustainable and ethical way forward, they are no longer tenable. They functioned for a long time, and we who made careers in them lived off them; but in truth they were harming us (and people in ‘the region’) all along. So, what would the academic equivalent of a green agenda in relation to the shatter zone of Russia’s various empires?

We need to think in terms of more complex ecologies of knowledge and seek insights and truths in the global ‘peripheries’, just as we might when researching climate change. Societies on the sharp end of the effects of global warming, mostly in the Global South, may through their experience and knowledge teach us something about those effects, as well as how to mitigate them in ways that do not reproduce structures of historical domination.

In the same way, perhaps we could consider global processes – cultural, political, economic – not through the study of the ‘main protagonists’ of history, but rather of those cultures that have had to live in and adapt to the devastating shifts in political climates. Can the geopolitical catastrophes of our day best be understood by only studying, say, the US and Russia? Or do Ukraine, Palestine, Sudan have something to teach us about our world? And what type of understanding results from the choice of the former over the latter?

For an institutional reform

If I imagined my ideal picture of where Ukraine would be in the structures of knowledge production, I imagine it something like this:

Ukrainian culture is studied in a multivectored way alongside the cultures with which it has interacted historically. Its culture is not a footnote to Russian culture, it is not an option you might throw in to a programme on Russia. The relationship with Russian culture must be studied, of course, but so must the relationship with Polish, Turkish, Crimean Tatar and Jewish cultures. At the same time, we must understand Ukraine as part of the European cultural ecosystem, plugged in to developments in Vienna, Berlin and Paris, as well as in Kraków, Budapest and Prague. And then we must understand hidden connections and parallels with more geographically distant contexts – with Mexico, Taiwan, Ireland.

To this end, I think of comparative literature (or comparative approaches to politics, history and economics) as a greener, more eco-friendly place for the study of Ukraine and all those other places we need to pull from the swamp of ‘Russia and Eastern Europe’. I don’t have in mind the sort of denationalised, depoliticised model of comparative literature convincingly refuted by scholars like Pascale Casanova and David Damrosch. What I propose, rather, is comparative studies that recognise the reality and value of the nation, of the distinct culture that must be studied in depth as well as in comparison, alongside the limits, shortcomings and dangers of the national as a paradigm, and the importance of recognising broader connections, parallels and interactions.

I can imagine programmes, publications and institutions that study the world in this way – where being a specialist in Ukraine would be a bonus, a sign that you understand important ideas and concepts from valuable perspectives. It would not be a ticket to academic obscurity, forcing one to sell one’s knowledge for its use in understanding Russia (I speak from experience).

But if we fold the study of Ukraine (or other countries of central, eastern, southeastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia) into bigger departments with broad disciplinary remits (Politics, History, Culture, Comparative Literature, etc.), isn’t this just condemning them to greater obscurity? Would they not become, to use another aquatic metaphor, even smaller fish in an even bigger pond? This is a genuine danger in today’s academic climate, which is so oriented towards simplification, rationalisation and profit maximalization that it is willing to sacrifice not just ‘obscure’ European languages, but modern languages tout court.

Even at the most pragmatic level, this is short-sighted: in a world that is increasingly unstable, isn’t it important to be able to understand the social, political, economic and, yes, cultural dynamics of the world’s hotspots? Shouldn’t politicians, policy makers, NGOs and businesses be interested in how societies at war exist? In how resistance works? In how statelessness and shifting borders shape migration, identity, socioeconomic processes? Isn’t the resourcefulness and ingenuity of the marginalised of value? If you are uninterested in poetry, think about drones…

My own School has a commitment to ‘critical area studies’, which recognises hierarchies and global interconnectedness. It is a great foundation on which to build. But like the vague field of east-central European/Central Asian etc. studies as whole, we are still too separate from other geographical contexts, still too inward looking – and the centre to which we are too often turned is Russia. Bridges are needed to help us cross the rushing streams of geopolitical contingency and speak about the intricate waterways of our respective areas.

Scholars of eastern Europe need to face outwards, away from Russia, and look to other contexts; we need to start seeing ‘our’ periphery as connected in complex ways to other parts of the world. We need more programmes and modules where students are reading Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka and Vasyl Stus next not only to Byron, Virginia Woolf and Sylvia Plath, but also next to Tagore, Derek Walcott, Zora Neale Hurston, Najwan Darwish. And the same goes for history, politics, social sciences and economics. We need to see our areas of study not as confined to some imagined geopolitical river basin, but as perched on the watershed between many such basins.

I know that this type of thing happens, occasionally, here and there. I know colleagues who are doing fabulous work precisely in this spirit. But it is not programmed into our universities, and it is not programmed into Slavic Studies in its various guises, which often seems to resist precisely the approaches I am describing. Here, we continue to be swept along down old waterways, along Pushkin’s forcibly redirected streams, along old canals that were hewn in a different world. For that reason, we are blind to the ways in which water actually wants to flow.

Kara-Murza later clarified his position and rejected accusations of imperialism as a misunderstanding.

I want to emphasise that it is possible to take an MA at UCL SSEES consisting of modules focusing only on the cultures of east-central and southeastern Europe, and in this wide scope my school is quite remarkable.

Transl. Vera Rich.

Published 8 September 2025

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © Uilleam Blacker / Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

House keys recur in the stories of Crimean Tatars and Palestinians displaced from their respective homelands in the 1940s, and Ukrainian citizens fleeing Russian invasion since 2014. Ethnographic research and discourses on art and justice show how objects emblematic of home salvage the history of exiled peoples from oblivion.

As capital consolidates, culture recedes, funding vanishes, access narrows. The question persists: why fund culture at all? Cultural managers from Austria, Hungary and Serbia discuss.