Two years ago, my body gave out. ‘Burnout’, said the doctor, as he carefully wrote out a note ordering me to stop all professional activities. His look indicated that I would be needing his signature more often. What followed was an arduous process of recovery in which I restlessly searched for a sense of purpose. I took daily walks, tried dry needling and bought watercolour pencils for therapeutic drawings I would never make.

The dialogue with my body came at least a couple of decades too late. I used to think of it as a fleshy vehicle that got me from A to B. It was only when my body started screaming that I was surprised to learn that it even had a voice. As far back as I can remember, ‘pushing through’ had been the best way to solve problems. ‘You have to teach your body to do things it doesn’t want to do,’ a teacher told me when I had a panic attack during a school trip. Restraining and reprimanding my body turned out to be not only a demonstration of willpower but also part of a cultural coming-of-age.

After enquiring at a few communal allotments and trying to enrol late for a semester of pottery, I finally ended up in the gym. In the pale light and grey-orange interior of a well-known self-improvement multinational, I felt my salvation was at hand. The gains that came from moving metal bars and mounting sweat-soaked saddles gave me a renewed sense of confidence. As complex and frightening as the outside world was, the simple satisfaction of pushing a little harder every day proved unbeatable. Hips don’t lie, and neither do upper leg muscles. But as I trudged along on the treadmill, I began to wonder if I was actually just running in circles. Something about my new routine was beginning to take on revanchist tendencies – as if I was going to teach my body who was really in charge.

The laws of the flesh

I clearly do not have the best relationship with my body. I see it as a business partner that I work with every day but secretly continue to mistrust. Perhaps this is part of the reason for my ambiguous fascination with action films. In action films, physical mastery is transformed into cinematic spectacle. Whether it is Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson bending steel beams or a battered Paul Mescal continuing to fight in Gladiator 2 (2024), bodies in action movies are always tools that the action hero uses skillfully and briskly. Tom Cruise’s compulsion to climb things or hold his breath until records are broken is symptomatic of a genre obsessed with mastering the human body. Just as action heroes do not look back at explosions, they do not care about physical limits. The fact that such acts are presented as heroic speaks both to the fantasies of cinema and to the social fabric in which we are made human.

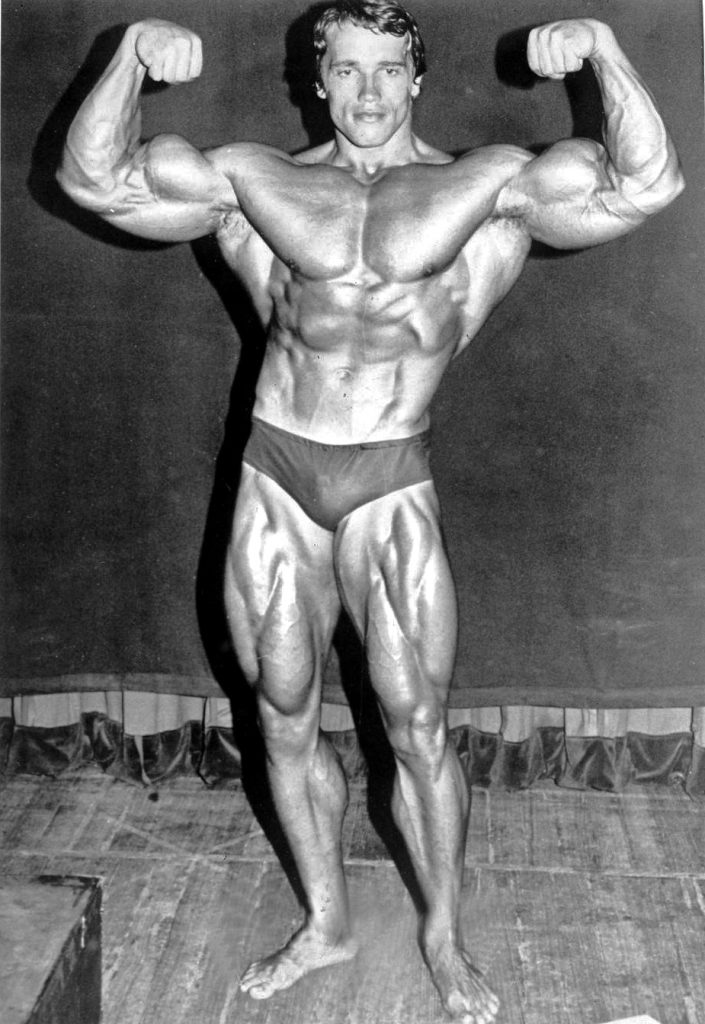

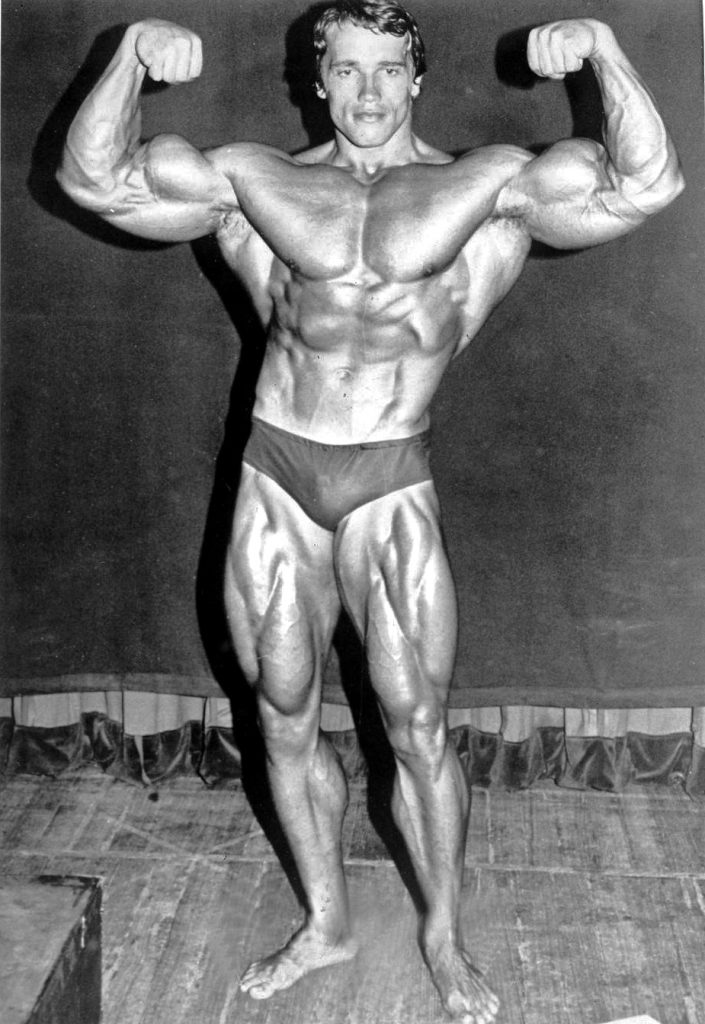

Arnold Schwarzenegger before his fifth Mr. Olympia contest win, 1974. Image source RMY Actions via Wikimedia Commons

It would be all too easy to dismiss the physical prowess of action heroes as merely an expression of crude machismo. When we think of the body politics and aesthetics of the genre, the imposing chest of an Arnold Schwarzenegger may be the first image that comes to mind. Such ideals of primal male power were already exaggerated in the 1980s – Arnie’s breakthrough years – and live on today only in media that both mock and fetishize them. When Hugh Jackman reveals his six-pack (or eight-pack, I forgot to count) in Deadpool & Wolverine (2024), a literal wink to the camera means we are expected to gaze at his body with a mixture of adoration and comic meta-reflection. Like the bulging biceps in the ‘epic handshake’ from Predator (1987), these carnal excesses are more suitable as meme material than human reference points. Contemporary female heroes are embedded in the same visual regimes as their male counterparts. Where women were once relegated to roles as love interests or sensual killing machines, films like Atomic Blonde (2017), Furiosa (2024) and Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022) show the action body as elastic across multiple identities and registers.

Beyond patriarchal tendons, a more deeply rooted relationship to the laws of the flesh reveals itself. What connects action heroes across time and space is their relationship to their own physicality. According to film scholar Lisa Purse, the action hero’s body is always defined by both trauma and triumph. Throughout the rollercoaster rides that these films are, the characters are subjected to a series of misadventures, which ensure that we can savour their ever-expanding running time. After all, says Purse, the core pleasure of the genre lies in the constant tension between losing control and regaining it. Whereas Heracles only had to perform twelve labours, John Wick has to travel the world for four films, shooting to pieces anything that looks even remotely suspicious. The true measure of heroism is the hero’s ability to control his own body and endure the increasingly intense effort.

Hard-bodied heroes

Remarkably, even though action heroes invariably possess superhuman powers, these films are mostly interested in finding their breaking point. As interesting as Spiderman’s talents may be, the stories only reach their emotional crescendo when the protagonist is immersed in a world of pain. Spiderman films reach their dramatic climax when Willem Dafoe smashes our hero through several floors of concrete in Far from Home (2019), or when the superhero is torn apart by two ferry halves in Homecoming (2017). With masochistic fervour, the action film invariably builds up to moments of (auto)mutilation. The fact that Timothée Chalamet voluntarily has a dagger plunged through his hands in the finale of Dune 2 (2023) to defeat his opponent shows that the path to success always crosses the boundaries of one’s own body.

The challenges these bodies face come in many forms. They can be exhaustion, injury, trauma, or other forms of physical or psychosomatic stress. Scenes of hardship are effective – not only because they build tension but more importantly because they encapsulate the essence of heroism. On the anvil of victimhood, the hero is forged into a man. The films show vulnerability only to refute it as a test to be passed. Connoisseurs of the genre have long known that action films are essentially adrenaline-fueled passion plays. Just as Christ faces new humiliations at each station on his Way of the Cross, so the action hero must face setbacks and difficulties again and again. But where the Son of God must humbly endure his earthly suffering, the action hero responds with excessive violence and bloodshed. Enduring pain, fear and hardship gives him a sacred right to retaliate.

This explains the action film’s obsession with torture. Since Rambo II (1985), the tied-up hero has become a standard feature. The hero is beaten, slashed or subjected to other brutalities, all of which serve to demonstrate the victim’s resilience. With the didactic enthusiasm of a cooking show, Rambo II highlights how electric current scorches the nervous system. However, the experience of pain does not prevent the hero from alternating his screams and curses with one-liners that further taunt the villain, masochistically increasing the intensity of the torture. In Gladiator II, we get delicious close-ups of searing pokers on our hero’s skin, or the camera gliding with perverse eagerness over fresh wounds. The slow-motion torture only serves to emphasize how unshakeable the hero is. The body may be bruised and battered, but the man stands firm and seeks revenge.

It should come as no surprise that such false images of masculinity feed national myths. Cultural studies scholar Susan Jeffords draws parallels between the film landscape of the 1980s and the United States of Ronald Reagan. Action films, in particular, presented the kind of unwavering, hard-bodied hero that the political and economic trajectory of the 40th US president demanded. As part of Reagan’s sweeping cuts to the public sector, society was repeatedly asked to step up to the plate. Resentful of soft men in hard times, the country found its mascots in Hollywood stars such as Sylvester Stallone, Chuck Norris and Jean-Claude Van Damme – or at least the chiseled bodies that represented them.

The fact that Reagan ran his re-election campaign on the slogans ‘Prouder, Stronger, Better’ and ‘Morning in America’ is indicative of the neoliberal fixation on self-improvement and perseverance. Action stars of few words and great muscle mass were thus supposed to symbolize simpler times, renouncing once and for all the morally complex 1970s – including the national trauma of Vietnam and the hippie generation. No more discussion: the hero was a man of action. His hard and untouchable body became a metaphor for the heroic recovery of the US. The heroes in films like Firefox (1982) and Missing in Action (1985) overcame their Vietnam-era wounds and used this triumph over their own bodies to fight new enemies.

Hardship makes the man

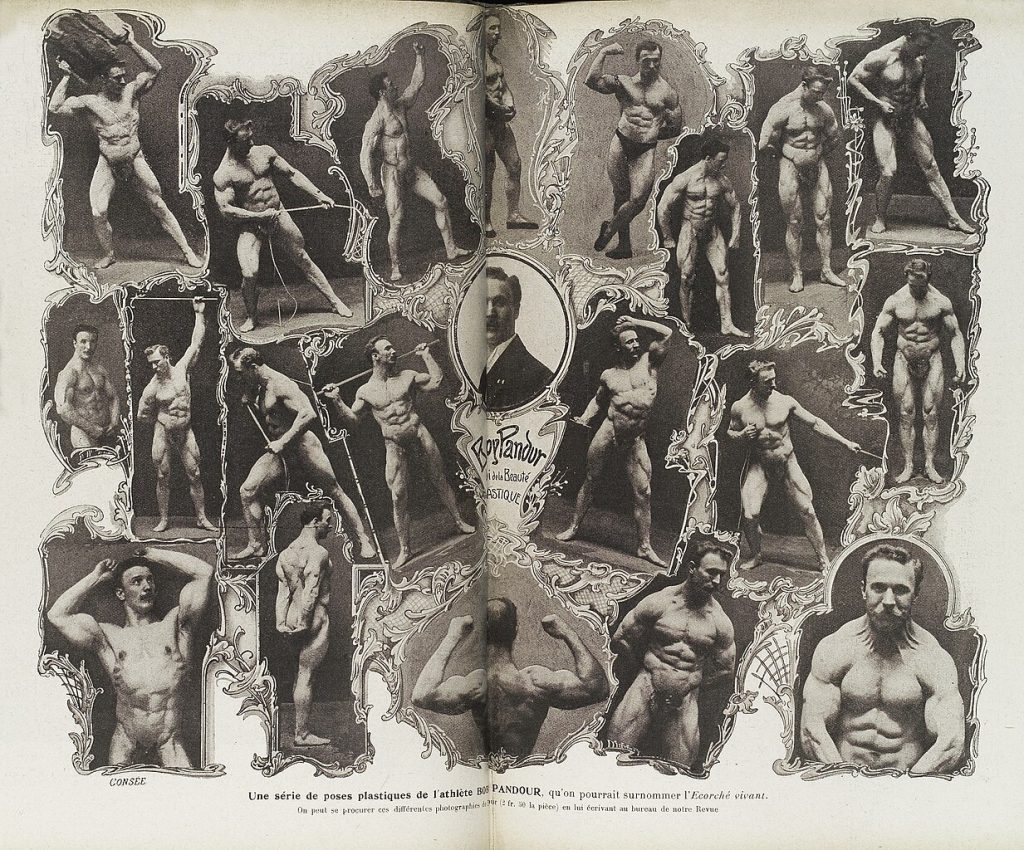

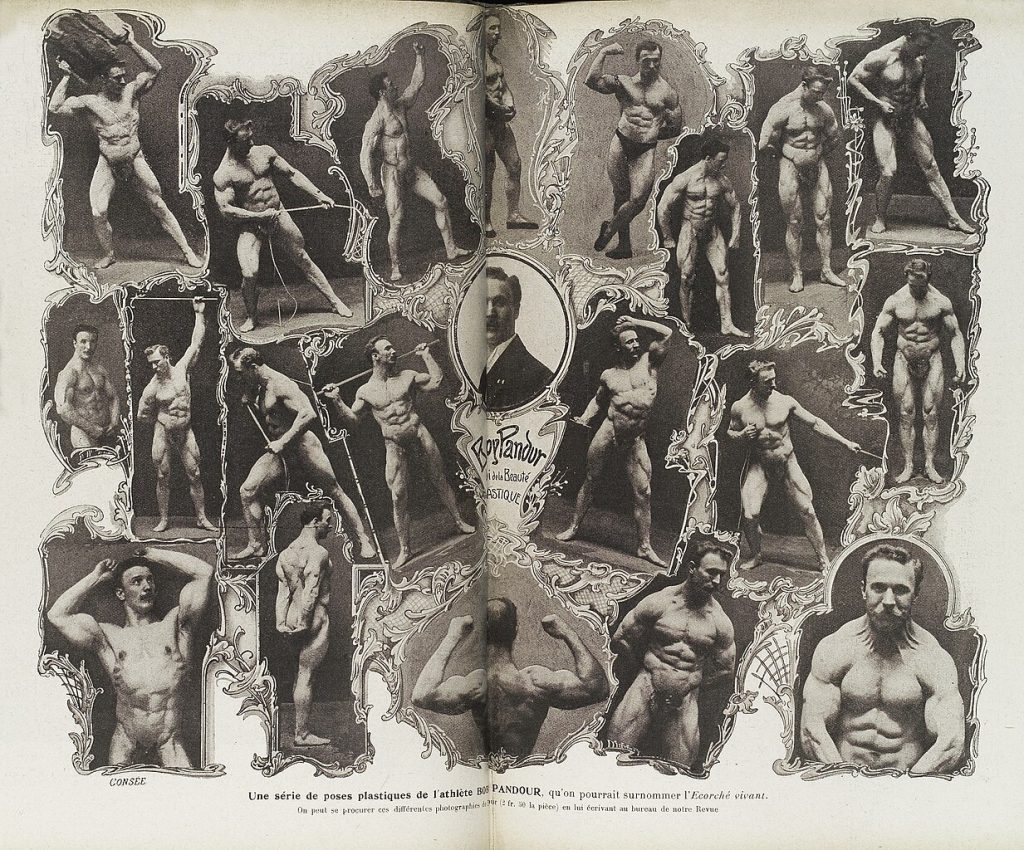

A series of semi-nude poses by body builder Bobby Pandour, c. 1906. Image from the Wellcome Collection, a website operated by Wellcome Trust, a global charitable foundation based in the UK via Wikimedia Commons

The beginnings of the action genre illustrate how bodies are always canvases on which the political power relations of their time are sketched. Notions of male recovery go back much further, however. Feminist film scholar Jonna Eagle uses the term ‘strenuous masculinity’ to refer to the dominant paradigm that links action films to our zeitgeist. She borrows the term from Teddy Roosevelt’s 1899 speech on the ‘strenuous life’. Referring to the American values of freedom and self-development, Roosevelt argued for the nobility of ‘effort’. Comfort was an anti-American quality; only through relentless work could the US achieve its destiny.

Eagle sees parallels between ideals of masculinity and how the modern world has developed since the mid-nineteenth century. As Western industrialization brought greater prosperity to the upper middle classes, the bourgeoisie began to lead more luxurious lives and manual labour was banished from affluent circles. But this increased comfort also marked a moment of crisis for men of higher social standing. How gentle could a gentleman be before he was no longer a man? Inspired by the romantic tradition, he sought out hardship. Camping, hunting, gymnastics and voyages of discovery became part of a performance to regain masculinity in a context where a luxurious bourgeois lifestyle was associated with feminine softness.

Such practices no longer pushed the body to its limits out of economic necessity, but became an identity-building pastime. This contributed to the idea that masculinity, according to western standards, had to be proven primarily by enduring discomfort. In this way, men look to gain control not only over a chaotic outside world but also over an equally unstable self. Like a wild horse, the body (and its associated emotions) must be tamed and forced into obedience. In action films, broken bones are set without too much drama and bullets are pulled out of bodies by hand. The body is a machine and needs to be treated and maintained as such. In characters such as Robocop, Iron Man and Bloodshot, the body is even literally fused with mechanical elements. It has reached its final stage as a metal suit that must obey the whims of its owner with upgrades, bonuses or medication.

This phenomenon is also reflected in the portrayal of villains. The validist standards of the action genre mean that villains are characterized by non-normative bodies and other traits that are considered repulsive in the action film universe. Moral evil is equated with what the genre understands as ‘physical defect’. Villains are characters ruled by the afflictions of their bodies, while heroes are masters of the flesh. Think of the physical condition of the villains in The Batman (2022), No Time to Die (2021) or Mission: Impossible – Fallout (2018) and you are on the right track. But the terror of the body also takes more subtle forms. Unlike heroes, villains sweat profusely, in keeping with the genre’s phobia of bodily fluids, or have small uncontrollable tics – think of Le Chiffre from Casino Royale (2006) who cries blood. Such images fit into right-wing nationalist gender narratives that depict the heroic male body as armour. Nazi propaganda, for example, contrasted the phantasmal, slimy skin of Russian and American soldiers with the stony exterior of the German ‘race’.

A battle for bodily autonomy is also taking place behind the camera. On the one hand, the contemporary use of VFX makes the relationship between body and mind even more unstable, as actors’ faces are superimposed on digitally fabricated bodies in post-production. On the other hand, the era of post-production CGI stunt work has created a new generation of action actors who use their own bodies as a claim to authenticity: now that action sequences can be easily simulated with computer effects, choosing to do your own stunts is seen as a sign of masculinity. As the stunt-driven promotional campaigns for blockbusters such as John Wick 4 (2023) and Mission: Impossible – Dead Reckoning (2023) show, the making-of is increasingly becoming part of the viewing experience. These films ask us to blur the lines between reality and fiction; we need to be fully aware of how difficult or dangerous a scene was for the actor in question. See how G-force distorts Tom Cruise’s face as he performs real jet manoeuvres in Top Gun 2 (2022)! Feel the suspense as Chris Hemsworth actually hangs out of a moving train in Extraction 2 (2022)! Action heroism is perpetuated by the ability of both the character and the actor’s body to function under extreme conditions.

Malleable bodies

In this sense, the world of action films bears a striking resemblance to French philosopher René Descartes’ dualism. In L’Homme (1662), Descartes’ treatise on humanity (or masculinity, comme vous voulez), the philosopher makes a clear distinction between the immaterial mind and the material body. If cogito, ergo sum (I think therefore I am), my body is put in a dubious position. According to Descartes, mind and body are also in a hierarchical relationship: the body is merely raw material to be subjugated to help us achieve our ambitions. As economist Jason Hickel argues, these dualistic views were at the cradle of capitalism. Just as nature could be plundered for its raw materials, it was only logical that the worker’s body could be efficiently squeezed for profit.

In action cinema, too, bodies are tools rather than living, experiencing entities. This helps to explain why rest, nourishment and affection are not events worthy of a place in action cinema. We never see a body in repose, recovering and waiting. Such views make the action genre a very contemporary one. Just as the action hero never has to refuel or reload his weapon, his body is nothing more than an idea in his mind; its vulnerable reality is never shown. The films present us with a fantasy of eternal growth, mobility and self-optimization. In a twenty-first century setting, we have all become action heroes to some degree, exploiting ourselves for reward and recognition on a personal or professional level. The HR lingo of self-improvement, resilience and perseverance has infiltrated many aspects of our socio-political life. Whether it is government slogans like ‘Flemish Resilience’ or the compulsion to be constantly online, stress is seen as a personal time management problem rather than a symptom of an underlying system. As a result, even in our leisure time, we are actively and incessantly at war with our own bodies.

Ironically, even a health crisis can be recycled within a capitalist framework. Daniel Craig will go down in film history as the burnout Bond whose main enemies were neuroses, alcoholism and post-traumatic stress disorder. In the sub-genre of geriatric action films such as the franchises The Expendables (2010-2023) or Taken (2008-2014) the heroes of yesteryear have found a niche as middle-aged men who can still kick ass despite their physical ailments. These afflictions need not be a problem for strenuous men; in fact, the ability to do what they do despite their ailments makes them even more manly. In other words, the failure of the body is not finite if it can be framed as a triumphant story of recovery or traded in the self-help industry. If it hurts, at least make sure the wound paves the way for new successes. And if not, there is a growing business model offering retreats, men’s camps and military-style fitness regimes offering solace. It shows how deep the neoliberal worldview has burrowed into our bodies, like a parasite that believes itself to be the host.

This article was first published by Eurozine partner journal rekto:verso. Its translation from Flemish Dutch into English was commissioned as part of Come Together, a project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.