Cosmic Europe

Merkur 12/2025

Leibniz’s Europe; why majority rule is relative; social chromatics off the scale; travels in post-capitalism.

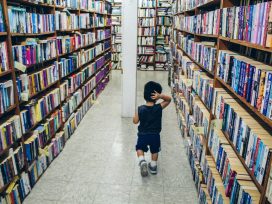

Against a backdrop of crime, corruption, inequality and sexual violence, Mexican novelists are returning to the tradition of the child narrator. Interviews with Fernanda Melchor, Luis Jorge Boone and Emiliano Monge.

Children as the bearers of a ‘question of hope’ appear in numerous works contemporary Mexican literature. They include Valeria Luiselli’s lost children, in the form of colonial history’s forgotten victims of the mass exterminations of Mexico’s various indigenous peoples, as well as the refugee children who, today, risk their lives crossing the border to the United States. They include Guadalupe Nettel’s children, who either never were born as a result of women’s chosen childlessness – which from a certain perspective may appear to be the only reasonable alternative in a futureless society – or who were born despite all and must be loved in all their vulnerability, despite the uncertain prospects. And they include the girls of the rising star on the Mexican literary scene, Dahlia de la Cerda, who find themselves in a constant struggle for survival in deeply patriarchal environments, as the daughters of cartel bosses, poor teenage mothers, victims of abuse, or murderers with no other option but to take the path of violence themselves.

These works build on a longer literary tradition in Mexico, where children seem to rise from the same kind of ashes. Examples include the short stories of Elena Garros or Amparo Dávila, where childhood is depicted as an illusory paradise in an alienating and violent world. Or Sergio Pitol, whose stories are often populated by damaged, often orphaned children (like their author). And not to mention Juan Rulfo’s unforgettable child characters who, cast into the wilderness of existence, seem to bear witness to a slowly collapsing society.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

When I travel to Mexico in 2024 to discuss the child in literature with the authors Fernanda Melchor, Luis Jorge Boone and Emiliano Monge, the presidential election is just around the corner. On Avenida Amsterdam, below the apartment I am renting on the border between the Condesa and Roma neighbourhoods, the trees are in bloom. Mexico City’s inner-city traffic is a constant hum in the background. When we sit and chat on the balcony, all three of my interview partners snort with contempt when the topic of the election comes up. The choice is between the rightwing candidate Xóchitl Gálvez, a businesswoman with roots in the indigenous Mexican Otomi people, and the left-wing Claudia Sheinbaum, a climate scientist, descendant of Lithuanian-Jewish refugees and now, a year later, Mexico’s first female president.

Neither Melchor, Boone, nor Monge seem to view the election as anything other than a sham in a political climate where corruption and a lack of real potential for change are seen as a given. What is the meaning of the child and the question of hope it represents in the context of such a situation? What is the role of literature?

‘Literature always makes a statement,’ says Fernanda Melchor, who has travelled from Puebla, where she has lived for several years. She was born in 1982 in the port city of Veracruz, located in the state of the same name. ‘So, literature is always political in some sense, but as a writer, I cannot think of my writing in that way.’How do you think about it?

As an exploration of the human beyond good and evil. Literature is beyond political solutions, it works with a completely different register. There is ambivalence and contradiction there, and political action cannot allow for that.

I often think about the raped child as a figure and theme in your books. You have many very vulnerable child characters, but you manage to portray a kind of inner child even in characters who are violent criminals and perpetrators themselves, an innocence that has been disfigured by other perpetrators in a perpetual spiral of violence. That inner child is both the site of an injury and of a dream of love and belonging.

When I translated your debut novel Falsa liebre (‘False Hare’, 2013), which was published in Swedish only after your international breakthrough novels Hurricane Season (2020) and Paradais (2022), that dimension of your writing became even more apparent to me. I thought a lot about paedophilic desire, which is a threat that lurks in all your books, but perhaps especially in your debut. Do you agree with that?

I haven’t thought about it that clearly, but it’s true what you say about the paedophile. You have your obsessions as a writer without knowing about them yourself, and patterns emerge gradually. Not all of my characters are as raped as Andrik in False Hare or Norma in Hurricane Season, but they all have a grain of paedophile victim in them, because they are part of a whole society of raped children. Polo in Paradais has lived a life where he was used early in life, especially by women – his mother and his girl cousin have taken liberties with his body, in different ways. His mother by exercising a matriarchal but authoritarian control over him, and his older cousin by playing sexual games with him against his will.

The great paedophile novel of modern literature, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, is also about exile and nostalgia. Is the nostalgic component also present in your characters?

Yes, perhaps. The desire for a child can be a desire for the past. A past that may not have existed. One case that struck me is Michael Jackson and his Neverland, how he surrounded himself with children to reclaim the childhood that had been taken from him.

There is a human comprehensibility here that does not diminish paedophilic violence. My own paedophiles – like the nameless man holding Andrik captive in False Hare, or Norma’s stepfather in Hurricane Season, who prey on her – are seduced by the young body, but they do not treat the children as children.

The Hungarian psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi, whom I used to read a lot, has the concept of ‘confusion of tongues’, which he believes takes place in relationships where a child is sexually abused by their carer. That interests me a lot, the confusion of language that makes the adult perceive a sexual desire in the child’s love, while really the child only speaks the language of affection. We adults speak of sexuality, our desires already corrupted by the experience, the awareness of death, the entry into an adult identity. But the child still only speaks and understands the language of the child, who seeks closeness without ulterior motives. There is a deeply unequal situation here, where the child is simultaneously treated as an equal, as an equal sexual partner. I think many of us experienced this confusion as children, if not through explicit sexual violence, then through being constructed as adults in relation to parents who were unable to come to terms with their infantile traumas.

For me, it’s been a place to revisit in my writing. I often like to extrapolate fiction into the sexual realm because it says so much about human beings and human behaviour. Because it is the realm of desire and experience. Young people who read my books, millennials, are amazed at how easy it is for my characters to get into various sexual situations – the average, young, middle-class reader of today is so much more protected than we were. They are so innocent! Almost like an asexual generation, sexually afraid. We were no less scared but that was the life we lived.

I often return to that idea of the confusion of language, because it touches me and speaks to me, it carries a truth about this child, as they say in English, being ‘parentified’ in relation to an infantile adult world. Norma’s mother is not the adult, she is a child, who drinks and goes out to chase men, and Norma is left with the responsibility of the siblings. Her stepfather, who becomes her abuser, has the same tendency.

In Mexican society, this infantilisation of the adult world is a social, and therefore political, problem. Mexicans love to submit to authority because we have an innate need to be children. And an adult who needs to be a child is a person who did not have those needs met at the time in life when they should have been met. There is an unrequited longing for tenderness, a longing that has been corrupted by other infantile adults. Populist leaders naturally capitalise on that need. ‘Submit to me and all your problems will disappear.’ For a person who has been hurt for generations, that promise becomes very tempting.

Do you think that this applies equally to men and women?

It depends. There is a strong tendency in Mexican society towards a cult around those in power, but in reality it is a very matriarchal society. In the cosmos of the Mexican child, it is usually the mother who is the authority, since the fathers are so often absent. The father is the dominant authority figure in public, on the street, in politics and so on, but the mother rules in the home. That is why she also becomes the greatest object of the child’s contempt. We despise what is close to us and desire what is far away, and in that order the father can continue to be idealized.

We despise our mother, and leave her, when we become old enough to leave or when we are pushed aside by rival siblings. Since the Mexican mother is always having new children, we are constantly competing for the coveted place where we are alone with our mother’s love. How can this continue in a society where women are, after all, largely wage labourers? Well, because the children are left in the care of grandmothers, great-grandmothers, aunts or uncles, and in this way the matriarchal sphere is maintained. Even when families can afford childcare, children mainly encounter female daycare workers and nannies – there are hardly any male nannies in Mexico – which makes it impossible for a younger generation of men to break this pattern. A man who wishes to be a primary school teacher or a nursery worker is seen as either gay or a pederast…

When the Morena party came to power in 2018, an entire system of private day care centres that had been financially supported by the previous government were all closed overnight due to corruption allegations. Now, the president said, the money would go directly to our grandmothers and great-grandmothers, who would once again take care of the children. There you have the enduring Mexican dream of the family as pillar of society – children should be raised by their family and thus be safe. The entire sector can be maintained by a society that imagines itself to be modern but still depends on the exploitation of women without legal rights, either by men or by other, more privileged women. The idea that there are bodies that we have access to, that we own, belongs to a class society with a very patriarchal ethos.

Is the paedophile mother also a child?

Yes, in the sense that when she appears in my novels she is almost always, or has always been, a girl with no way out. She represents a normality, and thus the normalisation of a rather poisoned relationship with children, with a cult around the young body. This is a global problem, of course. We are constantly surrounded by children’s bodies that we mistake for adult bodies, which are falsified as being adults, in fashion, sport, etc. And so we learn to desire these bodies. A normalised fetish. I try not to let my characters judge that social state, but rather to live in it, as we all do as human beings – we live in the societies in which we live, often without real reflection.

And there I try to take the child’s perspective, to be loyal to the child: when I talk about the paedophile, I always put myself in relation to the child. With Norma, whose rapist husband Pepe mistakes her longing for a father for sexual desire. This helps him to imagine that he is only ‘responding’ to her initiative. My task as a writer is to get as close as possible to Norma in this, where she too is part of the ambivalence of language and emotion, beyond right and wrong. When I was young, I loved Dennis Cooper’s and J.T. Leroy’s books for that very reason: the lack of judgement and the closeness to their characters. They are inside them, they are not held accountable or judged by an omniscient author, but are portrayed in their lives, without blinkers. How should one portray the child’s longing for love that we all share, and how is this longing sexualised? That is my great interest.

Andrik, like Leroy’s boy, has a strong, identifying love for his mother, which is partly why he later sells his body. He realises that his only salvation – which is an illusory salvation – is to submit to the desires of adults. It is his only survival, and a learned helplessness. I think many of us can recognise this from childhood, having to submit to the will of others to gain access to care and thus survival. In that way, he resembles Norma. I believe she resorts to violence and sexual exploitation because she knows that is what awaits her as a girl and woman in this world, she is fending off an order that has already defeated her. She orchestrates consent in order to avoid the violence she senses on the other side of a no. And this is also how her desire for her abuser is formed.

I am sometimes accused of writing pornographically, but for me the important thing is what is happening inside the characters. I absolutely believe that there are readers who get excited by the sex scenes, but I also believe that excitement can be necessary to see something, to feel and see a human condition. To see that in Norma, even during a rape, there can be pleasure, which often complicates trauma processing because there is a streak of guilt. But it is actually something deeply human, especially when we are talking about children as victims of rape, since the child has not yet learned to interpret sexuality and see the difference between care and sexuality.

It would be a betrayal of this child not to explore those complex layers of vulnerability. Andrik has to transform the pain when the nameless man rapes him, in order to survive mentally and physically. It is an aspect of the victim position that is impossible to ignore and that makes the violence that much more horrific and complicated. And it’s not just about the actual situations of violence. I think there is something very universal in that experience, in many children. Where does the violence and inequality of childish sexual play begin, where does the desire for discovery turn into something else?’

Luis Jorge Boone is not only a novelist and short story writer but also a poet. This is particularly evident in his second novel Toda la soledad del centro de la Tierra (‘All The Solitude of the Earth’s Centre’, 2019), which clearly deals with the child’s gaze and the question of hope. Boone was born in 1977 in Monclova, Coahuila, a region that often features in his books. Toda la soledad takes the form of a broken-line verse epic about a nine-year-old boy nicknamed Chaparrito, who is abandoned by his parents and brought up by Güela, his abuela – that is, grandmother or great-grandmother, which is not clear from the story and does not matter.

Güela is the head of the family when a family is without a father, a husband, and in this she is one Mexican woman among many. The location is northern Mexico, in an environment ravaged by violence and drug trafficking. Through the boy’s eyes, the story is told of a village demolished in the eternal cycle of the drug war. In the boy’s story, the voices of the disappeared are interwoven, as nameless and collective witnesses to what really happened in Los Arroyos, a small fictional town near the border with the United States. The novel’s plot is inspired by the Allende massacre of 2011, one of the bloodiest massacres carried out by Los Zetas, one of Mexico’s most brutal cartels.

How did the boy’s character in the novel come to you, how did you find his voice?

I came to this boy, who has no name but only a nickname, Chaparrito, when I was trying to find a way to tell the story in a form that could say something new about such a well-trodden phenomenon as cartel violence in Mexico. The boy became the entry point. I had never written from a child’s perspective; there had been young people in my short stories and my previous novel, but not children. It was important, perhaps even necessary, to find a way to approach such a dark and violent universe, so riddled with death, and doing so through the eyes of a child helped me get to a core that felt relevant.

I have always thought that ‘la literatura narco’, the literature that depicts cartel violence, always relies on the same kind of voices: the cynical, the violent, the narco, the avenger, the man who imposes his own law on the world. It is a voice that always contains the trap of idealisation, where criminal acts are portrayed as the only way out. We are given characters who supposedly ‘set the world right’ through counter-violence; it is the depiction of revenge as the path to justice, often accompanied by a semi-pornographic view of this violence. In this way, we get anti-heroes and anti-anti-heroes in an endless chain, voices that to me have ultimately always appeared as the same voice – a male voice, of course.

You said in an interview conducted before the publication of the novel that the people in the fictional village, just like Chaparrito, face their own ‘orphanhood.’ What do you mean by that?

The great lesson for me in writing this novel was to explore how even an adult world can feel the same orphanhood as a child in a world like that depicted in the book. That is, in a broken, corrupt society. The villagers in the novel, and in all the real-life villages that have been subjected to similar things, have lost their footing. They have lost faith and hope in a social structure, in any form of authority. They live in this hopelessness and this fear of unbridled, lawless violence, which is the shadow that constantly haunts them, pulling them down. In the face of violence, they are defenceless.

In Mexico, we have a peculiar dependence on hierarchies and the figures perceived to be at the top of the food chain. They become like symbolic fathers – the priest, the police, the lawyer, the mayor, the state governor, the president, but also the Aztec chief, because history goes back further and deeper than to our contemporary leaders and chiefs. There is a tradition of relying on figures that we imagine will protect us, but which, in a horrifying awakening, we are forced to realise will not do so. And this awakening is what plunges us into a feeling of orphanhood, of the loss of imagined parent.

We all continue to be the children we once were, but our task is to mature into the adult able to take care of that inner child, and thereby nullify this orphanhood, which is not a productive way of life, either on an individual level or a societal level. But our society is populated by adults who would rather fetishise their inner child, which turns into this idealisation of our own submission to incompetent authority figures, who take on the role of the imaginary parent. The need to be a child, to submit to authority, to be told, to obey, is also a way of remaining irresponsible – the responsibility becomes someone else’s. This, I believe, is quintessentially Mexican, a typical result of Mexican history. Through this infantilisation, a society allows violence and injustice to continue.

How did you work with the documentary materials surrounding the Allende massacre in 2011?

The Allende massacre was a series of events that took place in a village not far from where I was born in Monclova. But they also happened throughout the country. I move it to fiction so that the reader can also imagine a Michoacán, a Guerrero, a Tamaulipas, any of these places that have also been scarred by violence. In the same way, the boy is also my own inner boy, although I am approaching a childhood destiny that differs in essential ways from my life and my own childhood. Chaparrito is one of the many children who have had the most difficult childhood in our country’s history.

At the time of the Allende massacre I was living in Monclova, but it was only later that more details were revealed from people who had relatives there or knew people who worked there, or knew police officers involved. There were a lot of rumours and gossip. But the early years were characterised by the fear that there would be repercussions if anyone spoke out about, or even insinuated that the events had taken place. The press didn’t write about it until years later, and journalists started going there to report, to see the destroyed houses, to hear about the disappearances, to hear the stories of how the narcos had taken control of the city, and how it had become like a closed war zone, a bubble where nothing got out.

And then came the Netflix series Somos 2021, two years after your novel was published. But that was ten years after the massacre. Why was it quiet for so long?

The press knew that as long as the same cartel bosses were in power, nothing could be said. Unfortunately, this is very common. I myself knew absolutely nothing. But one day, I was invited, along with some other poets and publishers, to do a tour with readings in several different cities. We sat in a tour bus and travelled around for a whole week. And as we approached the border area, the driver said: Shouldn’t we go past Allende? And then he drove us to Allende and we got off at the village square where we bought soft drinks or something, and I started walking around with my colleague, and we saw such strange things, ruins of houses, empty, abandoned houses where the mud had poured in over the floors through the broken doors.

I went into bars and tried to ask people what had happened there, but no one would answer me. An eerie feeling surrounded the place. We never found out anything. But a few months later, I started reading the few publications that had begun to appear about the event, and only then could I begin to interpret what it was we had seen. It was primarily a major report by a female journalist from the United States, she was able to do it because she came from outside, but also because the bosses who had been in power at the time were either dead or deposed, and new power structures had been formed among the cartels. Which also means that these people will never be held accountable. Their guilt is already erased from history. I felt a kind of strange guilt at not having understood what I really saw there in Allende. It was from that feeling that the writing of the book was born.

The novel does not say where the parents disappeared to, they probably left for a better life somewhere, but they too could have been one of the disappeared after the massacre. Was this a possibility you had in mind when you wrote?

It is possible, as an unspoken reality. But it seems more likely to me that they fled to the United States to earn a living and escape poverty long before the massacre, because the city, which has a different name in the novel, although it becomes the scene of a veritable massacre, was also a bad place before that, a place of poverty and poor living conditions. His father disappeared like so many fathers before him, and his mother probably sought her fortune elsewhere.

Regardless, having a missing or absent parent is a life condition that is so prevalent in our society that it hardly matters. The missing may lie in hidden mass graves or have met their death as prostitutes or criminals in the cities, here or on the other side of the border, whichever. Today, Allende is a place that has lost a lot of people during the massacre – there is talk of three hundred people but there are other figures that indicate five hundred or closer to a thousand, which is an unimaginable figure in such a small community, person after person who is simply gone. Many of them died, but many probably just left without saying goodbye to their loved ones, to live a different life, with a different name, as undocumented immigrants in the United States or elsewhere in Mexico. Because they were threatened and unprotected, because they might have had the same surname as so-and-so, they were terrified and wanted to survive, and so they disappeared into thin air.

This means that those who remained behind do not know whether they ended up in the mass graves or escaped with their lives. I wanted to get closer to that uncertainty. As I said, it took a very long time for the event to be made public, and eventually the memory began to be institutionalised: the mayor who was then installed was related to the previous one, who had been part of the forces that wanted to stay silent about the event, and this new mayor created memorial sites and ways of collecting stories and evidence, under the pretext of remembering, of course, but also as a kind of backdrop or a way of taking control of people’s experiences, taking control of the voices, and thus control over the discourse, which then became the norm. Countries and institutions often create a culture of remembrance, with ostensibly good intentions, that can nevertheless often obscure or fail to encompass the whole story. And it is the individual story that disappears.

I am thinking of those Cubans who have come to the defence of the regime and continue to defend the idea of revolution, who oppose the blockade and take a certain political position – but in this too they are repeating a discourse that is increasingly empty, that does not produce anything original or specific, that repeats a slogan. You can compare it to German memory culture. When I come into contact with these institutionalised memory patterns, I often get the feeling of this repetition of something learned, but which doesn’t really go deep. I always feel distrustful of people who spout slogans, I am no longer talking to a human being but to an ideology.

Like Melchor and Boone, Emiliano Monge is a writer who has explored Mexican masculinity, particularly in the novels No contar todo (‘Don’t tell everything’, 2018) and Justo antes del final (‘Just before the end’, 2022), the former of which explores Monge’s paternal heritage and the latter his maternal heritage. Both take the form of autobiography, novel and memoir in one. No contar todo is the story of Monge’s father and grandfather, and at the same time a depiction of Mexico’s local history. The grandfather dramatically escapes his life and his family in the 1950s by staging his own death, only to return a number of years later. He becomes a father figure who abandons his duties and his ‘manly task’, but who is sacrificed and resurrected in a Jesus-like way: a kind of inverted prophet. Escapism and male identity are also the thematic core of the novel: Emiliano’s father, Carlos Monge Sanchéz, will in turn leave his wife and children in the 1960s to join Genaro Vázquez’s Cuban-inspired guerrillas.

Monge’s novels are often polyphonic and structured through several different voices, and the narrator in this supposedly autofictional writing is often made visible through the perspectives of others – the father, the mother, relatives. No contar todo, for example, consists of long passages of fictional conversations in which the father talks about the enigmatic grandfather, but in which the first-person narrator/author/novelist Emiliano has no voice of his own. The form becomes a dialogue flow with one voice removed.

Both books paint a self-portrait of the writer alongside portraits of the mother, father and grandfather – through a prismatic cacophony of narratives in which the hidden body that receives and becomes a receptacle for the others’ stories is ultimately the centre of the narrative. The novel’s Emiliano becomes a sickly and anxious child who escapes into his own imagination; he invents, pretends, confuses wishes with reality, lies – in other words, he is on his way to becoming a writer. He carries with him the fear of adult manhood, of both father and grandfather, of the seemingly inevitable task of becoming a man through equal parts flight, latent violence and callousness.

I think of the conversations with the father in No contar todo as a textual form in which the author is transformed into a kind of black hole, a silence, which nevertheless becomes strongly present precisely through its absence. I have also thought about that voice that remains unheard, as a sign of the impossible voice of the child. How do you think about that absent voice, which is the voice of the son, the voice of the child who speaks or does not speak to his parent?

‘When I wrote the novel, I didn’t think about it being a novel about my father, because I was too self-absorbed. The book was a big blow to my father when it came out.’

He is very harsh on his son…

Yes, but that is very Sinaloense, typical of men from Sinaloa. With the second book, the one about my mother, I thought I was being more careful, but it got even worse. My family ended up in a big conflict, with two sides opposing each other.’

Because of the novel?

They wanted to fight, they always wanted to fight, and the novel became an excuse to do so. I can explain to someone who routinely reads literature that it is not a pure autobiography, but that becomes impossible if that routine is lacking. Perhaps that absent son’s voice is also an expression of the same kind of self-absorption in me, I don’t know. But it is also an image of how we all, always, consist of other people’s stories, the ones we have inherited and often maintain collectively.

My father’s voice is the Mexican male voice that is completely integrated in me, that I cannot escape, that shaped me into who I am. And perhaps the son cannot really talk to his father until the father’s story has been told in its full glory. After the novel was published, I travelled to my father’s home in Valencia, Spain, and read it out loud to him, almost the whole novel, I sometimes read my texts to him. It became very charged.

There is so much pain in the dialogue with the father. But the son’s voice, which is emphasized in different ways by its absence in both novels – in the mother’s book by the narrator consistently addressing him, that is, herself, with a ‘you’ – marks a kind of impossibility of speaking, like an orphaned child speaking to his parents…

‘Yes, exactly! But aren’t all sons in some sense fatherless, because we live in a society that enforces a kind of inevitable absence in men? This is how we are brought up and expected to be. That was strong in my family, and we are certainly not unusual in that. In the world but especially in Mexico. This country is smouldering with male fumes, really… For me, it’s painful and infected because I myself am a man, and at the same time it’s my great interest. No contar todo is about three generations of men and how being a man, the idea of Mexican masculinity, has characterised them all.

But I must also emphasise that I do not see the books as autofiction but as fictional novels. While they are about my own heritage and exploring life stories that relate to a larger Mexican history, I have never interviewed anyone the way the father is interviewed by the author of No contar todo, for example. It is an invented form of telling something about my family, which is not just my family but is made up of people who have lived for a certain time in certain specific circumstances in this part of the world, in generations that meet and move away from each other. In this way, these two novels are about time, but it is a spiralling time, a time that is not chronological but moves in other ways.

Generations leave traces on each other that are not always clearly visible or discernible, or in a way that can be told in a particular pattern. What you draw attention to with your son’s voice is partly about that. The narrator is an adult or almost an adult but has all his ages in him, just as his father does, and his grandfather. Here is a child who never stops moving inside. The absence of the narrator in the conversation with the father in No contar todo perhaps marks the presence of a child who never ceased to be a child because he was also deprived of his childhood. The novel revolves around the question of what can break a genealogy of machismo in a child, since it is the narrator’s male heritage that is at the centre.

When you think of Mexican machismo, you understandably often think of those who have fallen victim to it. But one of its victims is also the men themselves, those who have to maintain it. Boys live in this impossibility that the spheres of action and emotion are completely separated, a boy is not allowed to cry but is expected to act in his life, he is expected to be a man, and in that is deprived of the right to be a child. Hombreciton [the little man] must be made into an hombre at all costs. The inner world and the world where the verb, the action, prevails, becomes a rupture between feeling and language in a child. The narrator in the novel shelters this child, who has fallen victim to that condition, victim of distorted language.

We often talk about the physical violence of machismo, but that violence cannot be thought of disconnected from the inability to give language to experience that lies at its heart. What is not said, the silences, thus become the undercurrent that disfigures life. If there is a place where the narrator hides in No contar todo, it is a place that has nothing to do with this: with the feeling of being in the shadow of one’s own life through the undercurrent of silences. And the silences and avoidances are the very nature of machismo. We can be ironic about the grim silence we attribute to men in a kind of simplistic stereotype, but the stereotype is also accurate. The silence is there, and it is tangible, even controlling how we live our lives and perceive our reality and ourselves. But silence also attracts us, it awakens the desire to know… And to write, of course.

How did you start writing the novel, what made you do it?

I had a lot of doubts about taking on the task. There was a fabric of myth and legend in the family relating to my grandfather and my father, both of whom who left their families in dramatic circumstances. I had always wondered what we, as a family, lived with in relation to our life choices, how we became the visible result of those life choices. I was interested in how a collective is created through myths and legends, and how they are created by what the myths avoid saying, by the silences of the stories, and what lurks in what is not said.

A child who grows up in an environment where there are unspoken traumas becomes a person whose entire existence revolves around eavesdropping on those silences. It happens out of necessity and becomes a guessing game about what is really going on – that is, an eavesdropping that constitutes the perfect breeding ground for a writer. Because such a child is always referred to his imagination, his empathy with the invisible and the hidden. The narrator in No contar todo and in Justo antes del final is this eavesdropping child, in the sense that he is confined to telling other people’s stories. He is this vessel for a larger story that simultaneously concerns himself and does not. Those old stories about how my grandfather faked his death and my father became a guerrilla man have shaped us as a family in a way I don’t think we can comprehend.

But again, this is not a biographical story, but literature, fiction, in every moment. I have to say this because the novels are about so much more than sometimes spectacular, sometimes comical and absurd events in my family history. They are an investigation, of truth and falsehood, through fiction.

Published 21 January 2026

Original in Swedish

Translated by

Diarmuid Kennan, Voxeurop

First published by Ord&Bild 2–3/2025

Contributed by Ord&Bild © Hanna Nordenhök / Ord&Bild / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Leibniz’s Europe; why majority rule is relative; social chromatics off the scale; travels in post-capitalism.

While book publishing is an ailing industry, children’s books are booming. But political attacks and censorship are also threatening this thriving sector.