Learning from erasure

Despite the uncertainty of recovery from ongoing war, Ukrainians are confronting Russian destruction and de-construction with daily acts of reconstruction. Marginalized landscapes, histories and stories are being rediscovered through a grassroots resistance founded on loss, where language and naming reclaim cultural foundations.

In July 2022, what started eight years before as the Ukraine Reform Conference reinvented itself as the Ukraine Recovery Conference (URC). Before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, this annual international event, attended by heads of state, a wide range of government officials, members of parliament, representatives of international organisations, civil society, and the private sector, was primarily focused on economic and democratic reforms in Ukraine. By and large, it was conducted within the discourse of international development aid, at a time when Ukraine was seen as just another country undergoing a lengthy transformation to catch up with the political and economic standards of the “developed world” or, at least, the European Union, and in constant need of supervision and various kinds of stimuli.

The focus change from “reform” to “recovery”, inevitably brought by the Russian war on Ukraine and the urgent need to express “support for the only country on the European continent currently affected by armed conflict” (as stated during the first URC in Lugano in 2022), was more than just a change in rhetoric. It was a major discursive transformation from the prescriptive certainty of “reform” to the complete uncertainty of “recovery”, both the meaning and the goals of which would be defined and redefined in the process. Even if not seen or fully comprehended in 2022, one of the biggest challenges for recovery in the Ukrainian case was that it had to be systematically planned and carried out while destruction was ongoing – an exceptional case in European and global history.

Moreover, this war, now in its fourth year, has proven to be a long one. Peace talks do not mean ceasefire, freezing the frontline does not mean an end to the drone and ballistic missile attacks on the cities deep inside the country, and any peace deal cannot secure a sustainable end to war. The most complicated negotiation point remains security guarantees.

Envisioning recovery and re-construction is not possible without constant witnessing and addressing destruction and de-construction on multiple levels. It is impossible to think about the recovery of the economy, critical infrastructure, energy security, transportation networks, or urban structures without acknowledging the destruction of the core connections and relations between people and their homes, communities, natural and cultural landscapes, but also memories, legacies, heritage, and identities. It is on this horizontal level of human, cultural, and environmental entanglement that the war is lived, destruction is experienced, and daily reconstruction and recovery are already happening.

Zemlia

In her recent book, Ecocide in Ukraine: The Environmental Cost of Russia’s War, Ukrainian researcher Darya Tsymbalyuk writes about death as the episteme of war: “It becomes the dominant morbid frame of learning about one’s homeland, when we only find out about the existence of someone or something when they are gone – erased, murdered, or destroyed.”1 The growing number of deaths and the extent of destruction creates a vast network, spreading over the whole society, linking everything and everyone.

In Russia’s war of aggression, landscapes, histories, and stories once destroyed, censored, crippled, or marginalised by the empire – first Russian, then Soviet – are being rediscovered through loss. This gruesome paradox of learning by erasure lies at the core of the recovering and regrowing connections between people, lands, and environment, at the core of the grassroots resistance to war and violence.

Tsymbalyuk puts soil and land (which in the Ukrainian language are embraced in one word, zemlia – a word she consistently uses, along with other Ukrainian terms) at the centre of the war experience. Being contaminated or destroyed, occupied or depopulated through the displacement of people and other species, zemlia stops being “a territory” and becomes a home, a shelter, a history, a living world.

In fact, the notion of “territory” belongs exclusively to the vocabulary of empire, as imperial imaginations erase peoples, homes, histories, and landscapes, reducing them to allegedly empty spaces and resources awaiting extraction. On the ground, the land – zemlia – is always a homeland, which cannot be simply given up, even for promises of ephemeral peace. This Russian war against Ukraine, which started in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and the temporary occupation of parts of the Ukrainian east, tore people away from their lands and homes and, simultaneously, reconnected them. The imminent threat of yet another erasure unearthed – sometimes in a very literal sense – previous losses and erasures, histories, legacies, and memories taken away.

In personal and collective relations, natural environments transcended their imposed agricultural or industrial functionality and imagery of the last centuries, recovering their meaning as cultural landscapes, which connect generations of people and layers of history, weaving links between them. This war also brought back the notion of “frontier”, not as a zone of clashes or conquests but as a space of constant contact, hybridity and complexity of relations, openness and multilayered identities in continuous flux.

Dakh

This year, another Ukrainian word made its way into the global language, trying to get a grip on this war – dakh. Originating in Old High German, it means “roof”. Dakh: vernacular hardcore is the title of the exhibition housed by the Ukrainian pavilion at the 2025 Venice Biennale. Dakh II and Dakh III were presented during the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Rome this year.

The foundation of the project is a 50-year monumental research work entitled “Atlas of Traditional Ukrainian Housing from the Late 19th to the Mid-20th Century”, compiled by three generations of women architects: Tamara, Oksana, and Bogdana Kosmina, the latter of whom co-curates the pavilion. “Dakh spans the trajectory of the Ukrainian home at war: a site of sanctuary, a terrain of destruction, a project of rebuilding – and a cradle of resistance,” writes Michał Murawski, another co-curator of the pavilion.2 Here, the roof is more than just an architectural element. It is a symbol of safety and protection, a basic structure that shields from violence and destruction, which falls daily from the sky. It is also a symbol of fragility; roofs are among the most damaged parts of houses, the crucial ones that volunteers have to rebuild first.

The Dakh structure consists of metal rods that form a load-bearing structure but also signify missiles and shrapnel, metal sheeting used in emergency roof repairs, and a wedge-shaped roof made of reeds. Its shielding capacity is not only spatial but also temporal: elements of traditional architecture come together with both assaultive and protective references to the current war. Vernacular hardcore, used in the title of this project, symbolically merges vernacular architecture – a sustainable way of building that relies on locally available materials, traditional or local architecture, grassroots architecture without architects – and hardcore as a fundamental part of processes, and as a mixture of bricks, rubble, and other hard materials traditionally used to lay foundations of buildings. This project rests against “a vernacular hardcore, rooted in the experience of generations, in the trauma of war, and in the power of resistance,” writes Murawski.3 Dakh envelops the space of simultaneity of destruction and reconstruction.

Together, zemlia and dakh delineate the shape of the renewed, but old, the recovered, but never really lost, the rebuilt, even if destroyed, home – dim. This is where solidarity stretches through generations and connects neighbours; where care embraces humans, non-humans, and wider landscapes; where steppe, rivers, estuaries, and forests are active fighters in the war and crucial participants in cultural history; where recovery and reconstruction, which started 11 years ago and never stopped, involves not only tangible assets – buildings, infrastructure, the physical environment – but also intangible ones such as heritage, memories, and identities.

Dim

“When the trenches were dug, cultural heritage spilled out of them,” states cultural journalist and curator Yuliia Manukian, using a somewhat brutal metaphor to link the changing attitude and understanding of cultural heritage during the war. Once seen as dusty and unimportant, emasculated, erased, or artificially constructed and imposed, cultural heritage has recovered a different meaning and sense of urgency through the episteme of war.

Resistance in this war is, among other forms, also epistemic. It involves careful and scrupulous revision and rethinking of how knowledge has been produced and shared, who has controlled the narratives, and how and why identities have been forged. Here, cultural heritage turns from the inheritance of the past into a living matter being formed in the present, an active liaison between the past and the future. Cultural practices become critical tools of reflection, embracing, acknowledging, and tracking the multiplicity of ways in which society organises, reorganises, and rethinks itself through legacies of the past, experiences of the present, and visions of the future.

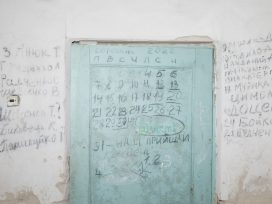

Manukian spoke at the conference entitled “Kherson on the Frontier: Steppe, River, Fortress”. It was the closing event of the exhibition Kherson: The Steppe Holds at the Mystetskyi Arsenal museum complex in Kyiv earlier this year. Both the exhibition and the conference were suggested as a frame to look at the region, which was once seen as inconspicuous and peripheral, brought into existence by the Russian Empire and further resourcified by the Soviet Union, and at the city. Kherson survived the brutalities of the Russian occupation in 2022 and the aftermath of the destruction of Kakhovka dam in 2023; located at the frontline, separated from the Russian-occupied territories only by the Dnipro River, the city was severely damaged, daily assaulted by drones and missiles. Yet it is still very much alive. How and why did people stay or return to the city in the face of permanent danger, looking after each other, temporarily abandoned houses, pets, and plants, and continuing to work on recovery and reconstruction as the daily destruction went on?

Architect and cultural heritage expert Andrii Lutsyk notes that “what is happening in Kherson right now is a cultural heritage of the future. A new or renewed identity is being forged before our very eyes.”

In the exhibition, personal stories, family legends, historical inquiries, local mythology, natural and cultural landscapes, and daily urban and rural rituals from the previous 30 years, times before the full-scale invasion, revealed the vernacular hardcore, a tight interlacing of various simple and often invisible or seemingly unimportant elements that connected people to each other and to their zemlia. This forms the core of identities that enable resistance in the face of death.

This exhibition, like the Dakh project or Darya Tsymbalyuk’s book on ecocide, like an exponentially growing number of other exhibitions, books, artistic and discursive projects and events, is an attempt to make sense of daily life inside the war, to trace the multiplicity of solidarities, local and nationwide caring networks of support and reconstruction – to pay tribute to those people, places, legacies, environments, taken by the war, to preserve their names and identities as a form of much-needed justice. This is culture as resistance, recovery, and security.

“Ukrainian culture in all its forms, with its history of resourceful resistance to imperialism and erasure in the face of Russian efforts to diminish its global reach, is an essential ally of open democratic societies in the fight against totalitarian threats,” writes Ukrainian researcher Sasha Dovzhyk in the editorial of the latest issue of London Ukrainian Review, dedicated to “Culture as Security”.

When spaces for democracies are dangerously shrinking and totalitarian threats are alarmingly growing, radically rethinking the role and place of culture in a new global security architecture and in the ongoing and future recovery of Ukraine is long overdue.

Darya Tsymbalyuk (2025). Ecocide in Ukraine: The Environmental Cost of Russia’s War. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Michał Murawski (ed.) (2025). dakh (дах): vernacular hardcore. Mini-Atlas. [The guide to the Ukrainian Pavilion at the 19th International Architecture]

Ibid.

Published 15 December 2025

Original in English

First published by Green European Journal 30/2025 (1 December 2025)

Contributed by Green European Journal © Kateryna Botanova / Green European Journal / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTNewsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

The sharp drop in support for Ukraine in Italy has less to do with the traditionally Russia-friendly economic policy of the Italian right, and more with the anti-Americanism rooted in the political culture of the Italian left, which now articulates itself as pacifism.

A combination of geopolitics and economic pressure is weakening the political will behind the European Green Deal, with the EPP leading the deregulatory offensive. Forests in particular risk becoming collateral victims of a rightwing U-turn.