Marija Gimbutas was the luckiest of scholars. She was the only twentieth-century scholar to have discovered and described an entire, unrecognized civilization.

Vytautas Kavolis

Most important, let us not cut off the bonds with the spiritual past of our nation.

Marija Gimbutas

One of the most renowned US archaeologists, Lithuanian-born Marija Alseikaite-Gimbutas (1921-94), created her own myth of extraordinariness. Like the goddess of light she describes in her work, she is acclaimed, respected, even adored. Having opened the door to the archaeological past of “Old Europe”, she built a unique methodology for which she coined the term archaeomythological. She explored Baltic mythology in depth and, having revealed the merits of the matricentric – what she called “matristic” – culture became an icon of feminist ideology. In 1991, she received the Anisfield-Wolf prize for her book The Civilization of the Goddess: The World of Old Europe published in that year. The prize has been awarded in the United States since 1935 for the most outstanding research in the history of world culture. A professor of Harvard and California Universities, this most famous of Lithuanian scholars addressed many questions that remain important in the twenty-first century, and was a dedicated advocate of the Lithuanian spirit. Her book The Balts, first published in 1963, remains the most popular introduction to the Baltic heritage worldwide.

The US has long been seen as a country of boundless possibilities: a land where dreams come true; a place that makes everyone free to become what he or she wishes. Yet things were not always easy for immigrants and the fate of Marija Gimbutas should be seen as an exception rather than the rule among such people.

She was born on 23 February 1921 in Vilnius and attended the Ausra girls’ gymnasium in Kaunas from 1931 to 1938. In 1942, she graduated from Vilnius University in Lithuanian studies, ethnology and archaeology. Having fled Lithuania with her family in 1944, she continued her studies at the universities of Heidelberg, Munich and Tübingen. In 1946, she presented her doctoral theses on burial customs in Lithuania at Tübingen University. From 1950 to 1960 she worked in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University; in 1955 she became a fellow of the Peabody Museum at Harvard, and from 1963 was a professor at the University of California (Los Angeles) where she taught Baltic languages, culture and mythology. The Pacifica Graduate Institute of the University now houses the Marija Gimbutas Library, along with the library of the world-famous mythologist Joseph Campbell, also a Professor at the University. It is no accident that their libraries share the same space: having rejected the elitism of the academic world, both scholars were dedicated to communicating their message to society at large and to remaining in touch with their public. Regardless of criticism in scholarly circles and the dismissive attitude to much of their work, they were not afraid to propound daring hypotheses and to bring their broad, visionary sweep to bear on building attractive, subjective, mythical visions. Neither was blinded by their great acclaim, whether it was their popularity with students, attention from TV and the press, multiple editions of their books or fame and adulation.

She was born on 23 February 1921 in Vilnius and attended the Ausra girls’ gymnasium in Kaunas from 1931 to 1938. In 1942, she graduated from Vilnius University in Lithuanian studies, ethnology and archaeology. Having fled Lithuania with her family in 1944, she continued her studies at the universities of Heidelberg, Munich and Tübingen. In 1946, she presented her doctoral theses on burial customs in Lithuania at Tübingen University. From 1950 to 1960 she worked in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University; in 1955 she became a fellow of the Peabody Museum at Harvard, and from 1963 was a professor at the University of California (Los Angeles) where she taught Baltic languages, culture and mythology. The Pacifica Graduate Institute of the University now houses the Marija Gimbutas Library, along with the library of the world-famous mythologist Joseph Campbell, also a Professor at the University. It is no accident that their libraries share the same space: having rejected the elitism of the academic world, both scholars were dedicated to communicating their message to society at large and to remaining in touch with their public. Regardless of criticism in scholarly circles and the dismissive attitude to much of their work, they were not afraid to propound daring hypotheses and to bring their broad, visionary sweep to bear on building attractive, subjective, mythical visions. Neither was blinded by their great acclaim, whether it was their popularity with students, attention from TV and the press, multiple editions of their books or fame and adulation.

Marija Gimbutas’ greatest influence was Jonas Basanavichius, who looked for reflections of the Lithuanian way of life and religiosity in folklore, mythology, history, ethnography and archaeology. She was an archaeologist by profession and a mythologist by vocation. In 1990, Antanas and Aleksandra Gustaichiai wrote in a letter to Gimbutas:

Our dear friend Marija, while sending you a photo of the Mother Goddess, which, as you see, has given birth to all of us, I thank you dearly for your letters and apologize for a maybe somewhat dilettantish advertising of your excellent book, which has never been written by any of our forefathers or any man striving for international fame […] True, recently for a couple of nights I’ve been listening to the dialogues on mythological themes by Joseph Campbell on TV, who confirms your line of thought.

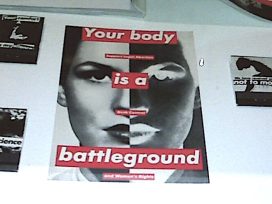

As the founder of the new discipline archaeomythology, which links two academic disciplines and conforms to interdisciplinary canons, Gimbutas still boasts a considerable number of followers; despite the passage of time and the mixed reception with which her work was received, the style and tone of her writing, remains extremely suggestive. The Great Goddess gives meaning to the essence of femininity. It is no accident that Gimbutas’ books are shelved with feminist literature in bookshops around the world.

The appearance of Gimbutas’ key works coincided with the rise of feminism in the US for which she became a distinguished apologist, founder and authoritative figure. Her works outlived the 25-year time span conventionally allotted to research in the humanities. “It would be enough for our short-lived immortality that anyone reads us after 25 years (more are allotted only for rare geniuses in philology),” reflects the prevailing view among scholars who see it as a reasonable measure of the popularity of their works.

How should Gimbutas’ popularity be assessed? Her style of writing and interpretation that rejects scholarly esotericism and is oriented to readers who have no time to analyse the authenticity of research and the depth of meaning, satisfies a demand for self-identification – the need to identify oneself with the past, clearly simply and understandably, without being confronted with scepticism or doubt. A peaceful stance, psychologically suggestive, clear and evocative, prompting matricentric identifications, and a pleasing narrative approach that has simple aims: to generalize, show, convince and encourage.

In 1960, Gimbutas wrote to her Lithuanian colleague Professor Meile Luksiene in response to criticism of her new study on symbolism in Lithuanian folk art:

I planted my seed as well as I could. I don’t have the opportunity to go back to the same topic, though it was once my dream. And probably I would have done something more. But I satisfy myself even with that small contribution, as I was writing with love and verve. And it will remain a memorable detail of my biography. I worked conscientiously, and I don’t really care if the truths that I nurtured and built will be truths for others as well. Such is the nature of scholarly work, the only important thing is that it doesn’t do any damage.

Strange as it may seem in these times of an overall heightened sensitivity to one’s self-image and the loss of self-reflection, Gimbutas considered criticism an important part of the assessment of her work:

I found these critical remarks a great satisfaction. It is seldom that you get a chance to read basic criticism, which you agree with. Yes, instead of two thick volumes a small booklet was written. I reflect on the facts, digest them inwardly, and don’t have time to expound everything that I know. Probably it is contrary to my nature.

Endowed with a bright, constructive mind, she had an exquisite ability to look at everything simply and sincerely, to choose clearly and achieve seemingly impossible things. “Don’t break into an ironic smile, my dear,” she wrote to Lithuanian writer Marius Katiliskis about her life in the US in May 1964, “a great deal is possible in this country, one only has to keep trying; I have the license to say that as I myself have gone through thick and thin.”

Life is like a mythical quest in which we are challenged by seemingly insurmountable trials by fire and ordeal. By overcoming them, one becomes stronger: “The weather was stormy, waves were beating against rocks. And then a massive shower began and we had to run home breathless.” Often lonely and instinctively running away “from thoughts and reality”, Gimbutas fed her insatiable desire for learning by immersing herself in scholarly research.

The fact that she chose mythology seems an excellent though intriguing solution. Despite its outward simplicity, mythology is a fairly complicated structure surviving in the present only in fragments. It is intricate and multi-faceted, dispersed in virtual time, and with a great many deceptive ideological and textual dead-ends. These latter should not be explained as authentic signs of the past or at least are not worthy of it. This is one of the many traps of mythological games.

Referring to the thoughts and research of Algirdas Julius Greimas, Jonas Balys and Jonas Basanavichius, Gimbutas wrote, “Mythology, which can also be called cultural archaeology, reflects the same features of Baltic culture as archaeological monuments.” The search for analogues, parallels and common features requires erudition, intuition and competence. An outstanding and highly skilled expert in archaeology with vast experience of excavations and with an extraordinarily broad ranging vision and intuition for prehistory, she lacked the narrative skills and ability to justify her solutions and images. In any case, it was never her aim.

The main stimulus of her research was a calm, simple and wise realization of what you do and why. Gimbutas’ book The Balts published in English in 1963, Italian (1967), German (1983) and Lithuanian (1985), remains the major publication surveying ancient Lithuanian culture for a global readership; the weight of its authority excludes any rival. In it, she tried to answer the questions that interest Lithuanians living abroad: “What do we have in common with other people in the world, and in what do we differ from them.”

The Lithuanian scholar, who remains the greatest authority in the humanities and who created a unique system of representation and assessment of early culture drawn from her wide range of observations and comparisons of facts and phenomena, did not lay claim to the absolute truth (based on generally recognized and objective criteria).

A vision of the early world, the epoch of the Great Goddess, seems the opposite of the established identification model in the masculine world of today. Gimbutas did not choose to follow Clifford Geertz’s “thick” description – an anthropological term used to describe human behaviour within it’s specific context in a way that makes it intelligible to the outsider or observer – rather, she composed the world lightly and suggestively, avoiding superficial propaganda and clichés. She identified the past by asserting its matricentric origin, hierarchies and reincarnations of gods untrammelled by the limitations imposed by academic requirements or conditions, and resolutely built her own truth.

Such truths are usually received with harsh criticism:

Like many here [in Lithuania, RR], I think that a mythological system can be built only by referring to the demands of life that determined the formation of mythology (different in each country) and not by looking for an absolute idea that would link all mythological approaches (suitable for any nation). It is not credible that the primitive human mind should be capable of creating an abstraction that divides the spiritual and supernatural world according to the principles of male dynamism and female vitality […] The established system does not allow us to reveal the historical stratification of religious-mythological views: the Lithuanian Olympus is regarded as being set once and for all. Thus, we have to refer to a very hypothetical existence of the Great Goddess.

Goals, ideas and propositions become important when they correspond to existential views, consumer demands or a search for identity. Then other laws take over: authenticity, validity and completeness are eliminated from the range of problems, and meaningfulness is determined by a sole criterion the urgency of the need. The Great Goddess and her epoch became that lucky coin, the formula of “eternal youth”, which enriched the expression of femininity with special connotations.

There is a tradition of holding readings in memory of Marija Gimbutas and anthologies are published in her name. From Realm to Ancestor: An Anthology in Honour of Marija Gimbutas, compiled by Gimbutas biographer Joanna Marler and with texts by 50 outstanding scholars from 13 countries, was published in 1997 in Manchester, Connecticut. Varia on the Indo-European Past: Papers in Memory of Marija Gimbutas, a collection of essays on the Indo-European past, edited by Miriam Robbins Dexter and Edgar C. Polone, was published in Washington in the same year. The Marija Gimbutas museum or research centre is planned for Vilnius, in the former apartment of her parents Veronika Janulaityte-Alseikiene and Danielius Alseika. On the basis of the archaeomythologist’s works, virtual histories of goddesses are written. Her lectures on the early culture of the goddesses, archaeological tokens and discoveries are published in audio and video formats. In 2004, the filmmaker Donna Read made Signs out of Time, a documentary on Gimbutas’ life and work – her Baltic origins, the mythical spread of the Lithuanian spirit, phenomenalism[…]

An outstanding personality, a thought-provoking scholar and an extraordinary woman who, despite being immersed in the past was ahead of her time, Gimbutas is acclaimed globally; her fame reaches far beyond the conventional human limits of time and space. It confirms her own words that “vital energy cannot perish, it survives[…] Our dead are among us”. As are their ideas, works and ventures, which confirm the bond with the spiritual historical past and create new, significant experiences.

Gimbutas also opened the door to the rich treasury of Baltic mythology in Lithuania and encouraged artists to explore the expression of mythicism. Yet the “conversion” into the faith of the Mother Goddess was as difficult in this country as it was in the US. In their letter to Gimbutas, Antanas and Aleksandra Gustaichiai wrote with regret, “After that I tried to convince even our neighbour, Dr Juozas Girnius, of the feminine gender of our creator, but being a religious conservative, he remained faithful to his male God-Father.”

While receiving the award of the Woman of the Year of Los Angeles Times in 1968, Gimbutas said, “I am grateful to the Goddess of Fate for creating me a woman – a creature equal to a man. However, we women still need the help of wise men.”

Having revealed the basic mysteries of existence, having discovered and described “an entire yet unrecognized civilization”, Gimbutas remained (was able to remain) true to herself not only in Lithuania, but also on the other side of the Atlantic.

She was born on 23 February 1921 in Vilnius and attended the Ausra girls’ gymnasium in Kaunas from 1931 to 1938. In 1942, she graduated from Vilnius University in Lithuanian studies, ethnology and archaeology. Having fled Lithuania with her family in 1944, she continued her studies at the universities of Heidelberg, Munich and Tübingen. In 1946, she presented her doctoral theses on burial customs in Lithuania at Tübingen University. From 1950 to 1960 she worked in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University; in 1955 she became a fellow of the Peabody Museum at Harvard, and from 1963 was a professor at the University of California (Los Angeles) where she taught Baltic languages, culture and mythology. The Pacifica Graduate Institute of the University now houses the Marija Gimbutas Library, along with the library of the world-famous mythologist Joseph Campbell, also a Professor at the University.

She was born on 23 February 1921 in Vilnius and attended the Ausra girls’ gymnasium in Kaunas from 1931 to 1938. In 1942, she graduated from Vilnius University in Lithuanian studies, ethnology and archaeology. Having fled Lithuania with her family in 1944, she continued her studies at the universities of Heidelberg, Munich and Tübingen. In 1946, she presented her doctoral theses on burial customs in Lithuania at Tübingen University. From 1950 to 1960 she worked in the Department of Anthropology at Harvard University; in 1955 she became a fellow of the Peabody Museum at Harvard, and from 1963 was a professor at the University of California (Los Angeles) where she taught Baltic languages, culture and mythology. The Pacifica Graduate Institute of the University now houses the Marija Gimbutas Library, along with the library of the world-famous mythologist Joseph Campbell, also a Professor at the University.