What Chris Marker wrote in 2006 as a tribute to his faithful travelling companion and sound engineer, Antoine Bonfanti, could equally well be applied to himself: ‘The evolution from this kind of inspired improvisation to absolute mastery is not just a process of professional improvement. It is also a process of political and moral reflection and of reflection about the very nature of sound.’ Marker himself did not feel he should distinguish between politics, morality and art. In his view, expressed in Le Fond de l’air est rouge (A Grin Without a Cat, 1977), people who create cinema are ‘witnesses and militants’. This view is perfectly consistent with someone who committed himself to many different struggles, from the French Resistance to the anti-colonialist movement of the early 60s or, a few years later, to the small groups that carried out ‘agitprop’ using anonymous ‘cinétracts’, or during the war in Yugoslavia, when he used static shots to film a young UN peacekeeper.

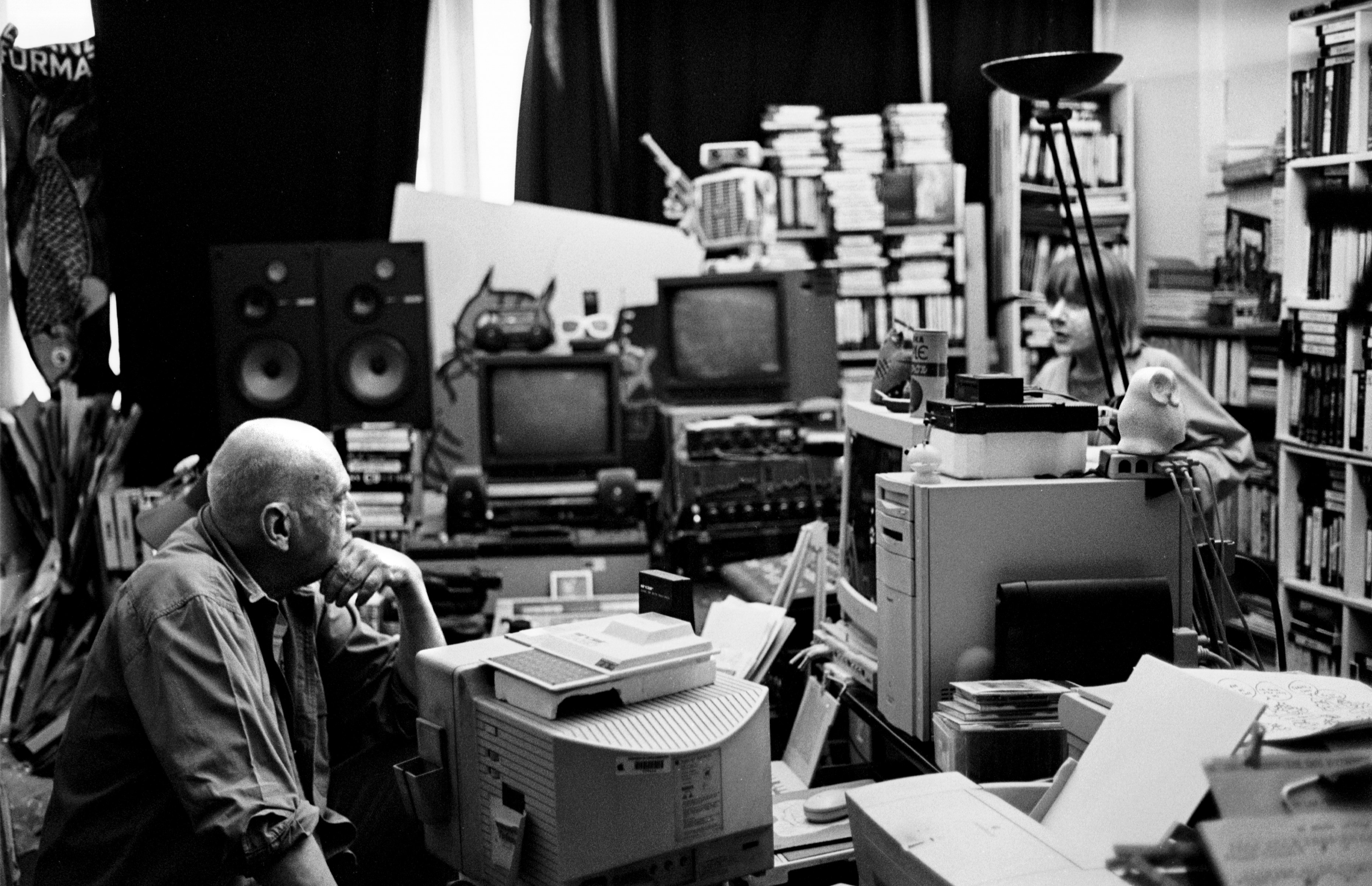

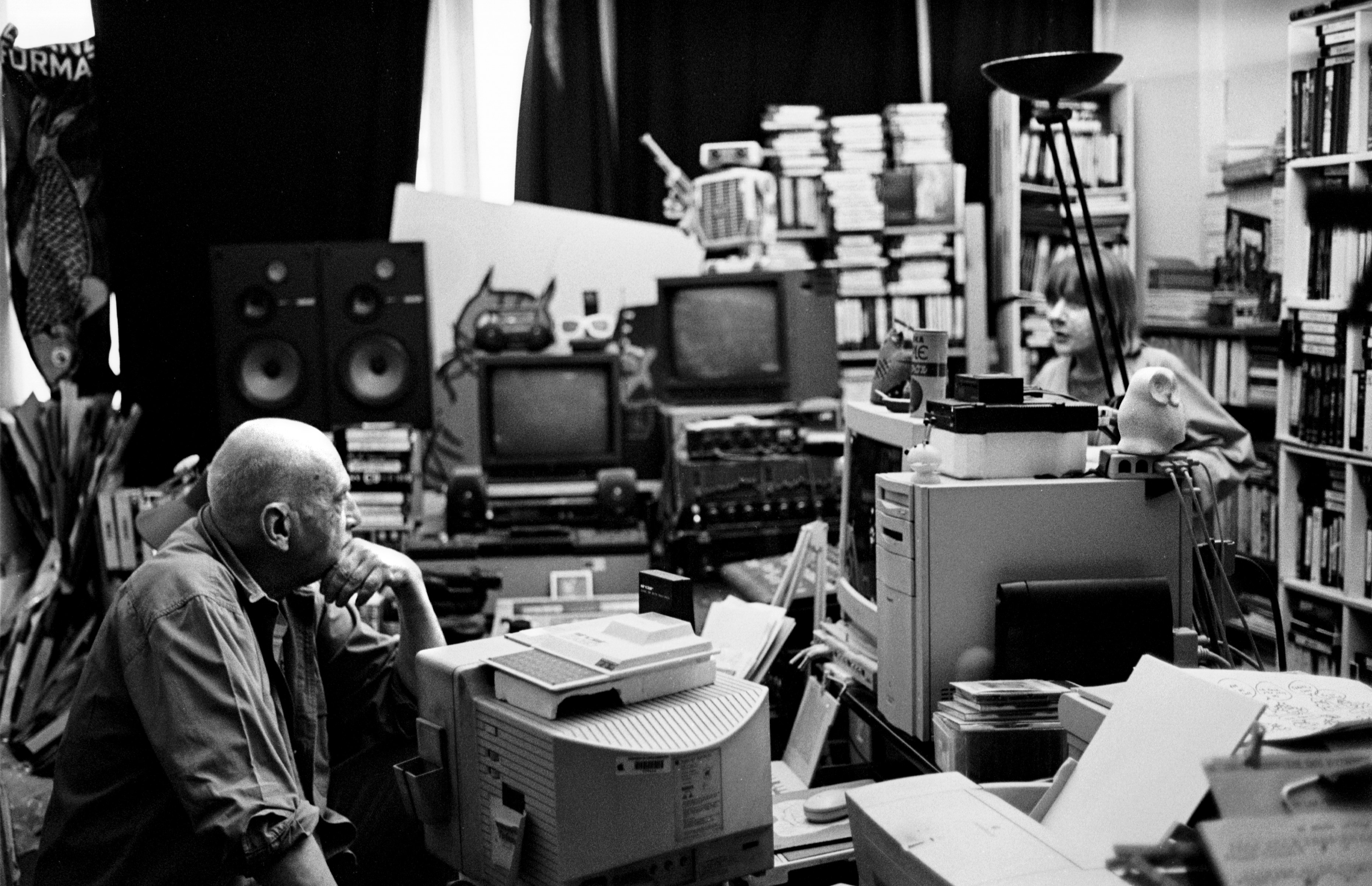

Chris Marker in his studio on rue Courat, Paris, May 2000. Photograph by J.-F. Dars.

The sparsity of resources

Militant cinema functioned without money, so improvisation was more a necessity than an intellectual stance. Even so, Marker used improvisation throughout his film-making career, including in those films that had no specific political commitment. He did not try to make some sort of theory out of this practice; the most he allowed himself were playful comparisons. During an interview for the launch of the film Level Five (1997), he spoke of his ‘imaginary Meccano’: ‘The film is a whole, I proceed on the basis of intuition; the parts fit together like the pieces of an imaginary Meccano set. I never ask myself if, why or how.’ Hence the frequent switches from one technique to another: 3D, software-based animation, collage, drawing, critical writing, fantasy, installation, the internet. In Level Five, for example, Marker mixes 16 mm and video, multiple screens, computers, photography, super 8, super 16, television, video and website. Marker tries everything without any prejudices. In Le Joli Mai (The Lovely Month of May, 1962), he uses a portable tape-recorder that had been used for Rouche and Morin’s Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer). In doing so, Marker finds himself in step with the beginnings of the Nouvelle Vague which, disengaged though it was from political concerns, also took advantage of the lightness of new equipment that enabled filming in the streets. Later, Marker filmed Immemory (1997) with software originally meant to familiarize primary schoolchildren with CD-ROMs. Finally, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, while the rest of the world was turning its nose up at the internet, he invented a virtual life for himself in the 3D-world of the video game Second Life. At the age of almost ninety.

Describing how these short films were ‘manufactured’, Jean-François Dars and Anne Papillault, who crossed paths with Marker in the mid-1960s when working on the ciné-tracts, talk about how he prepared heaps of photos that he made available to everyone, amateur film-makers or well-known directors. All could help themselves in order to make two- or three-minute films, often silent. Sometimes, certain images reappear, to the point where they become emblematic, especially one of a CRS officer wearing a helmet and dark glasses, which turn him into a terrifying Cerberus. These films, intended as agitprop, consisted of a montage of still, black and white photos that were filmed and then separated by intertitles or fades to black. The film camera would sometimes zoom in on the images to draw attention to a detail; work on the images was carefully thought out; the composition of the words, set out almost as a calligram, would transform them into images. One can recognize in this device not only the techniques of militant cinema, but also the mechanism used in La Jetée (1962).

This exploration of various techniques should not be seen as fascination with technology, but as a search for the right medium. How are we to recount a story? How should we present it? Marker’s response to these questions is not based on big budgets; this is just a feature of how his Meccano works. Echoes of this austerity can be seen in the sparseness of the props he uses for the torture scenes in La Jetée, a science fiction film set during the Third World War: just a mask over the eyes, some electric wires and the fiction takes form. Similarly, one is struck by the economy of resources that characterizes his film A.K. (1985) on the making of Kurosawa’s Ran. Using Super 16 and a minimal team, Marker is not trying to compete with the Japanese super-production, but is above all determined to demonstrate the work of Kurosawa, keeping the camera on him for long periods to catch his reactions and to make us understand his working methods. This strategy is all the more fascinating in that the way Kurosawa himself works is precisely the opposite to that of Marker: the Japanese film-maker tries to grasp every minute detail, to bend reality to his fiction in the same way that classic cinema does, be it that of Hollywood or Japan.

Sometimes, Marker will linger over a point that he sees as sensitive. He often co-signed his films with his sound engineer, Antoine Bonfanti, or his chief cameraman, Pierre Lhomme, thereby rejecting the preeminence of the director in the ‘auteur’ cinema of his day. In A.K., he stresses the collective aspect of the filming process. Even though Kurosawa, whom Marker refers to as ‘Sensei’, is the undisputed master, it is evident that Marker takes pleasure in filming the first assistant, the director’s right-hand man, strewing cement on the ground to simulate dust. Is he seeing himself in such images? The humility that he showed on this set is a fundamental feature of his work and may also be seen in the omission of his name from the credits of some of his other films.

Le Joli Mai provides us with an opportunity to appreciate the sparsity of the resources and Marker’s aesthetic, moral and political premises. An interviewee is eulogizing about the power of individual will while a spider is running up his jacket. The camera zooms in on the creature. When the man – the inventor of stabilizers for light cars – claims that all inventors are a little crazy, his interviewer reacts to the comic aspect of the situation and says: ‘Oh yes, you mean they have a spider on the ceiling?’ (‘une araignée au plafond’, roughly: ‘bats in the belfry’). When editing the film, Marker chose to keep this incident in. It works as an instance of collective creation, shows his attention to details of the present moment, and introduces an element of distance without harsh criticism of the man’s triumphant liberalism. Obviously, Marker does not share his individualism, but his generosity is apparent in the sequence that follows. The camera team are with the inventor in a Renault Gordini, testing the stabilizers. Even on the bends of the Montlhéry race track, the driver can let go of the steering wheel and the car holds the road. Having paid tribute to the man’s skills, Marker makes a final dig. The inventor is explaining that, behind every great man, there is a woman supporting him, ‘a second wheel’. Within the overall narrative of this great political film, this assertion can stand because it belongs to the person who said it. The two directors, Chris Marker and Pierre Lhomme, can thus debunk an ideology without scorning on the person who upholds it. All this through watching a pretty little spider crawling up a bit of cloth!

Such modesty characterizes those who seek whilst remaining close to what is real. These aesthetic, technical essays, which cannot be separated from his conception of films and his political vision, make it possible to understand Marker’s discreet work on subjective memory. Talking about Level Five, he states: ‘Contrary to what people say, speaking in the first person in films is a sign of humility’, adding that ‘I have nothing but myself to give’. It is on the basis of individual experience that the film-maker can connect with the ‘us’, in a process that combines classical reserve with political engagement. A position between the subjective and the collective.

In Letter from Siberia (1957), the first-person pronoun is an anaphora: the voice-over says at the beginning: ‘I’m writing to you from a distant land’, and then later on: ‘I’m writing you this letter from the land of childhood’, and then finally: ‘I am writing you this letter from a distant land’.[1] This rhetorical figure is an echo of a demonstration, now part of the accepted canon, of the influence of the commentary on the meaning of the image track. Three times, Marker reruns the same image sequence but attaches different commentaries each time. What is striking is that the supposedly ‘objective’ version is no more convincing than the snatch of Soviet ideology. He points this out in a voiceover: ‘But objectivity isn’t the answer either. It may not distort Siberian realities, but it does isolate them long enough to be appraised and consequently distorts them all the same … A walk through the streets of Yakutsk isn’t going to make you understand Siberia. What you need might be an imaginary newsreel shot all over Siberia.’

Inventing a reality that has not yet existed is one of the ways in which Meccano works. At the same time as paying scrupulous attention to the real, Marker does not conceal his interest in the imaginary: ‘For someone like me who has only ever been able to create a cinema-object out of fragments of reality, the autonomy that the imagination has is impressive.’ This attraction dates from before he began to make films. He wrote ‘imaginary news’ for Esprit, which was often both mordant and very funny – for example, in 1947, when he imagined General de Gaulle being received into the Académie Française and taking the seat left vacant by Pétain.

In his works, the real is a prerequisite for creation, something that is common both to the documentary and to fiction – albeit in a different way. Marker is very happy to play on how these two forms interconnect, even though, until the end of the twentieth century, they were seen as being mutually exclusive. In that respect, then, his cinema is truly innovative. Consequently, he confronts the taboo that, in the militant 1970s, required all possible confusion about the origin of the images to be removed, on pain of excommunication from the congregation of political cinephiles. L’Ambassade begins with a warning: ‘A Super 8 film found in an embassy … this is not a film; it is notes made from day to day…’ And the ‘hand-held’ filming, pretending to be the work of an amateur, contributes – fifteen years before Eduardo Sanchez and Daniel Myrick’s Blair Witch Project (1999) – to making you believe that you are seeing a documentary in the strict sense of the term, one that is built on the basis of ‘found footage’. It is only the last shot that brutally tips the ‘documentary’ into the realms of science fiction, when we realize that ‘this city that we had known when it was free’ and which is today beneath the yoke of a dictatorship, is Paris. As always with Marker, the coup de théâtre is deliberately rough and ready: a simple panoramic shot shows the Eiffel Tower in the distance.

Hence a fundamental dynamic: just as Marker never refuses to use any kind of medium or technique, so he also never avoids using any kind of narrative mode, ensuring that the ‘I’ that speaks of the ‘We’ also creates the meaning.

The sense of play

In 1962, Lévi-Strauss published La Pensée Sauvage, the same year as two essential films: La Jetée and Le Joli Mai. Lévi-Strauss also puts forward a certain form of subjectivity when he states that the improviser does not ‘limit himself to accomplishing or carrying out, he “speaks”. Not only with things … but also by means of things: relating, through the choices that he makes between a limited range of things, the character and life of the author, without ever fulfilling his project, the improviser always puts into it something of himself.’ Concluding his reflection, Lévi-Strauss situates the artist midway between scientific knowledge and magical thinking.

At the start, Lévi-Strauss explains improvisation as being based on two absences: that of a plan completely set out in advance and that of a hierarchy in terms of the materials used. He contrasts improvisation with an engineer’s plan and attributes it to ‘savage’, or at least non-western thinking. Leaving this cultural dimension aside, let us concentrate on Lévi-Strauss’s celebration of a practice often denigrated by those for whom only organized, rational procedures are worthy of interest. Improvisation is ‘carried out using “the means at hand”, that is, a necessarily limited and disparate collection of tools and materials, because the composition of the whole is not related to the plan of that particular moment, nor indeed to any particular plan. Rather, it is the contingent result of all the opportunities that have arisen to renew or enrich the stock or to feed it with the residues of things earlier constructed and destroyed’, which Lévi-Strauss later refers to as ‘residues and debris of events’. This brings to mind of the entire work of Marker, beginning with his own rushes, archives, photos or found films. Or his apparently naive attempts with software packages that had only just come onto the market, as in his Théorie des ensembles (1990), a short mathematics teaching film, which resembles a piece of cross-stitch needlework. Whilst the animation technique may seem rudimentary to us today, Marker was here again a precursor.

In his exploration of the concept of improvisation Lévi-Strauss also describes an operation that bears a curious resemblance to editing: ‘the decision (made by the improviser) is dependent on the possibility of switching some other element into the vacant function in such a way that each choice will be the cause of a complete reorganization of the structure, which will never be the same as the one that was vaguely dreamt of nor any other that might have been found preferable to it’. As we know, Marker edited his own films, and this operation remains an essential feature of his art just as important as his camera work: it is in the editing that the conception of the work is crystallized. He sometimes edits in a classic fashion, especially when making an educational or popularizing film, or also when he was co-directing. Such is the case for La Sixième Face du Pentagone (The Sixth Side of the Pentagon), which follows the march of 21 October 1967 on the nerve centre of American military power and mixes fixed images and shots in situ. Immersed among the demonstrators, the camera goes right up to the doors of the Pentagon, a rifle-shot away from the soldiers guarding the entrance. This politically committed film is as wise as it is chronological, something that does no harm whatsoever to the demonstration.

L’Héritage de la chouette (The Owl’s Legacy) is a series of twenty-six minute episodes, whose declared aim is to define the contribution of Greek civilization to the modern world. The series was broadcast on FR3 and on Arte in 1990. In one episode, ‘Nostalgie ou le retour impossible’, Marker has the viewer gently slide from shots extracted from Odysseo, a silent film by De Liguro (1911) to images of modern Greece, interspersed by interviews with Greek and European intellectuals (Vassilis Vassilikos, George Steiner). He gradually negates what, at the beginning of the film had been presented as incontrovertible: the strength of our Ancient Greek heritage. Admittedly, little girls of today can be christened Persephone but, from one sequence to the next, you can see how invasions and wars brought about a hybridization of a culture that had been claimed to be free of external influence. Just to reinforce the message, Chris Marker the editor inserts the beginning of Elia Kazan’s film, America, America (1963), where the narrator speaks in the first person just as in one of Marker’s own films: ‘My name is Elia Kazan. I am Greek by blood, Turkish by birth and American because my uncle went on a voyage.’ The voice of the American film-maker then continues with an interview filmed in 1989. We have moved from the discourse of academic experts to proof provided by a film, confirmed by the words of its creator. While leading us to revise the myth of a great unified Greek civilization, the film at the same time offers a nostalgic version of its inheritance, suggested in the suffering affecting Greeks of the diaspora, forced out of their country by poverty or by the dictatorial regime of the Colonels. It would be difficult to imagine an approach to editing that is more classical and intelligent: once the film ends, the meaning of the title becomes crystal clear.

Even so, like his contemporaries in the world of militant cinematography, Marker has no qualms about using the technique of ‘montage’, inherited from Soviet cinema. Many studies have discussed Marker’s use of montage, which is associated with political cinema, so we will restrict ourselves to a single example. In Le Joli Mai, a beautiful young blonde states: ‘I might turn into a rough sleeper, it’s something that obsesses me quite a lot.’ Marker contents himself with inserting just afterwards a shot, lasting just two seconds, of an old woman whose state of physical decrepitude contrasts sharply with the arrogant beauty of the young middle-class woman.

Anything can be grist to the mill of an improviser, even the chapter structure of a CD-ROM that invites the user to browse and enjoy the delights of serendipity. Except, of course, that the sudden appearance of unexpected images has been carefully engineered by Marker, who is perfectly happy, as he says, to get away from the ‘arrogance of the classical narrative’, especially when it is applied to his favourite theme: ‘Strangely enough, it is not the immediate past that offers us models of what computerized narration on the theme of remembering might be like. It is too dominated by the arrogance of classical narration and the positivism of biology.’

Through his interest in editing, Marker became the heir to the pioneers of cinema, the Lumière brothers. In 1993, in Slon tango, he films an elephant (‘Slon’ in Russian) in Ljubljana Zoo. Like the earliest filmmakers who could only film as long as their magazine would last – less than a minute – he takes a single shot of a dancing elephant, claiming that, as he was filming, he thought about Stravinsky’s Tango and, once he got back to the studio, put it on the sound-track. Whilst that may be so, Marker goes against the Lumière model of the fixed frame: he refocuses on the wounded skin of the animal. The elephant goes back into its box. The tango ends three or four bars later, the time it takes for three intertitles. Marker thus doubles the stakes: not just a single shot but the precise duration of a musical work. By reusing a technique dating from the beginnings of cinema, one that reduces editing to two cuts, one for the start and one for the end in a single shot, this improvising artist – or free artist if you wish – detaches himself from the model to achieve an astonishing result. In less than five minutes, he makes us dream of the grace of an elephant and faces us with the plight of captive wild animals, in a shot that combines political and moral reflexion with reflexion on the nature of cinema itself, to paraphrase his own words that are quoted in the introduction. Marker uses every facet of editing, from the practices of experimental cinema to those of plastic arts, but he cannot be classified into either of these categories, just as he refuses to be content with ‘montage’, linear editing or the virtual aleatory. He seems rather to proceed like those who built cathedrals, prepared to reuse pagan materials to build churches. In this sense he is close to Jean-Luc Godard in Histoires du cinema (1988).

What is more, Marker worked as credited director and as collaborator at the same time. He acted as a cameraman for Haroun Tazieff’s Volcan interdit (1966) and wrote the commentary for Resnais’s Nuit et brouillard (1955). But we must not forget that despite being committed to the collective, Marker the artist did much of his work alone: designing in front of his computer or editing his films. When they speak of him, Jean-François Dars and Anne Papillault emphasize two notions that encompass the concepts of improvisation, commitment, morality and reflexion on cinema. In their view, Chris Marker is a ‘joueur’ (player). Rather than seeking truth, he is interested in the meaning of things. Perhaps the same élan that combines seriousness and spontaneity is what brings the notion of improvisation close to that of play. Indeed, Lévi-Strauss put etymology at the root of the idea: ‘In its older sense, the verb bricoler (improvise) pertained to ball games and billiards, to hunting and horse-riding, but always denoting an unforeseen happening: a ball that bounces back, a dog that goes off the track, a horse that turns aside from the straight path to avoid an obstacle.’ In that sense, you might think of a game as it is played by children: intensely. To recognize in his magnificent works a childlike dimension is to pay homage to a grown man.

Much has been written about Marker, but not much about how interested he was in children, how often he filmed them, photographed them, celebrated them. In a shanty town, adults watch the television, children stare at the camera. In E-clipse (1999), after the eclipse has been shown full shot, the opening of the iris reveals a little girl who is lying stretched out on the statue of a hippopotamus. Throughout this short film, Marker films adults who are looking at the moon. Only the children and the film-maker do not turn towards the event that is meant to be the subject: is their curiosity about the real, about life perhaps the same?

It certainly seems that the treatment that a film-maker gives of a child’s face reveals something about his art. It is only great artists that do not get bogged down in stereotypes when they try to represent children. Marker, however, observes them – and above all sees them – as individuals, not as some idealized, and hence consensual, essence. In Si j’avais quatre dromadaires (‘If I had four dromedaries’, 1966), the commentary voice (Pierre Vaneck) makes it clear: ‘It is no more the case that there is such a thing as a “united childhood” any more than there is such a thing as united nations. Children are, first and foremost, what they eat and what they are taught … Children are not a fatherland. At most, they have a family, the great family of humanity.’