In an era when the sole approved artistic doctrine in the USSR was Socialist Realism, the Moscow collector George Costakis built up a unique body of Russian avant-garde art, alongside numerous early Russian icons, revealing deep-rooted links between the two genres.

The avant-garde was banned in the USSR for over five decades. Between 1932 and the end of the 1980s, Soviet artists were compelled to abandon any creative experimentation. The work they had once done, held in museums throughout the country, was hidden away and sometimes destroyed. Yet at this time, George Costakis (Moscow 1913 – Athens 1990) built up a unique collection of avant-garde art dating from the 1910s and 1920s, which he preserved alongside the antique Russian and post-Byzantine paintings he had also assembled.

Today, it is widely acknowledged that the Russian avant-garde made a substantial contribution to uncovering the aesthetic meaning of early Russian icons. Academic studies analysing the icon as a source for the Russian avant-garde are extensively available. In this context, the historiography of Costakis’s collection is of significant historical and cultural interest.

In the 1960s and 1970s, the collector’s flat in Moscow (which consisted of eleven or twelve rooms) was considered by many as a project for a ‘museum of the Russian avant-garde’. Alongside experimental objects d’art, it displayed traditional Russian icons and a collection of folk toys, while also offering a substantial library and archive. The numerous distinguished cultural and political figures who came to see the exhibits included Edward Kennedy, David Rockefeller, Michelangelo Antonioni, Marc Chagall and Igor Stravinsky. But it was not until 2014 that a sizeable part of the collection was shown to the wider public at an exhibition organized by the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, commemorating the 100th anniversary of Costakis’s birth.1

Symbols and connections

Overall, the collection was by no means exceptional, even for its time. The items on display did not bear comparison with the pre-revolutionary collections of Ilya Ostroukhov and Stepan Ryabushinsky, for example. However, for the first time, Costakis’ collection drew clear links between religious iconography and the paintings of early twentieth-century Russian avant-garde artists. Costakis introduced the Russian avant-garde to the West, while also making an important contribution to the study of connections between the icon and avant-garde art generally. He demonstrated how folk art and iconography could enhance the understanding of specific features of the Russian avant-garde in the context of twentieth-century modernism.

Costakis described the beginnings of his fascination with icons in the following way:

I started by collecting icons alongside avant-garde works. Initially I wasn’t particularly interested in the icons. I didn’t understand them and had no feeling for their qualities as works of art. In general, iconography failed to move me. But avant-garde art opened my eyes to the meaning of icons. I began to see that the two were intimately related and profoundly interconnected. I came to recognize elements of abstract painting and suprematism, and all kinds of universal symbolism, in iconography … Over time, I managed to assemble a large collection of icons – about a hundred and fifty painted panels dating from the fifteenth to the seventeenth centuries.2

It is clear that Costakis saw icons as an integral part of his collection and, as the owner of a substantial library and archive, he must have been familiar with academic ideas about links between the icon and the avant-garde. He had been collecting literature and documents on the subject since the early 1950s. His library included Alexey Grishchenko’s book The Medieval Russian Icon as an Art of Painting (Moscow 1917), which described, in some detail, the Russian avant-garde’s preoccupation with the icon. The archive also included Alexander Shevchenko’s famous manifesto ‘Neo-primitivism: Its Theory, its Possibilities, its Achievements’ (1913), as well as the catalogue for the Exhibition of Icon Painters’ Manuals and Popular Prints, a display organized in Moscow by Mikhail Larionov in 1913.

The sources Costakis trusted most, however, were the surviving representatives of the early Russian avant-garde, who convinced him of the importance of links between their work and iconography. In his memoirs, Costakis devotes special attention to his relationship with Marc Chagall, who had painted works influenced by icons and religious popular prints in the first decade of the twentieth century and, later, completed a series of paintings on Biblical subjects. The two men are very likely to have discussed ‘the icon and the avant-garde’ and corresponded on the subject.

An indirect confirmation of this can be found in Costakis’s account of his relations with the French cultural attaché, Alexandre Kem, who passed on letters from Chagall to him from 1952. ‘We spoke about Chagall’s art,’ Costakis writes, referring to a conversation with Kem. ‘I drew parallels between the icon and his work.’ During his first visit to the West in 1956, Costakis was introduced – through Chagall – to Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, in whose art the icon played a vital role.

He also met Nina Kandinsky, who owned Russian folk icons from the nineteenth century, previously belonging to Wassily Kandinsky and now held by the Kandinsky Fund at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Several icons from this collection were first shown in 2011, at the ‘Chagall and the Russian avant-garde’ exhibition in Paris.

In Moscow, Costakis was in touch with many icon collectors, scholars, writers and art historians. He was not alone in seeing the influence of iconography on the Russian avant-garde – the specialists who advised him on assembling his pieces were equally aware of the link. The most important figures included Russian scholars Nikolai Khardzhiev and Dmitry Sarabyanov, as well as the Western art historian Alfred Barr.3 Nonetheless, the connections that had a special significance for Costakis were with artists themselves – especially representatives of the so-called ‘second wave’ of Russian avant-garde art in the 1960s and 1970s.

This group of artists saw icons as ‘pure art’, in exactly the way they had been interpreted by the early Russian avant-garde in the 1910s and 1920s. Small collections of icons, housed in the flats and studios of artists such as Dmitry Krasnopevtsev or Vasily Sitnikov, created the impression of a world apart, a free private space, independent of Soviet life with all its restrictions. While Krushchev or Brezhnev were in power, the beauty and reverse perspective of medieval icons seemed to counter the dogmatism and monotony of the Soviet system in the minds of people associated with unofficial artistic circles. At the time, Costakis was also collecting paintings by artists of the second Russian avant-garde, including Dmitry Plavinsky, Dmitry Krasnopevtsev and Vladimir Nemukhin.

Liturgical art and folk primitivism

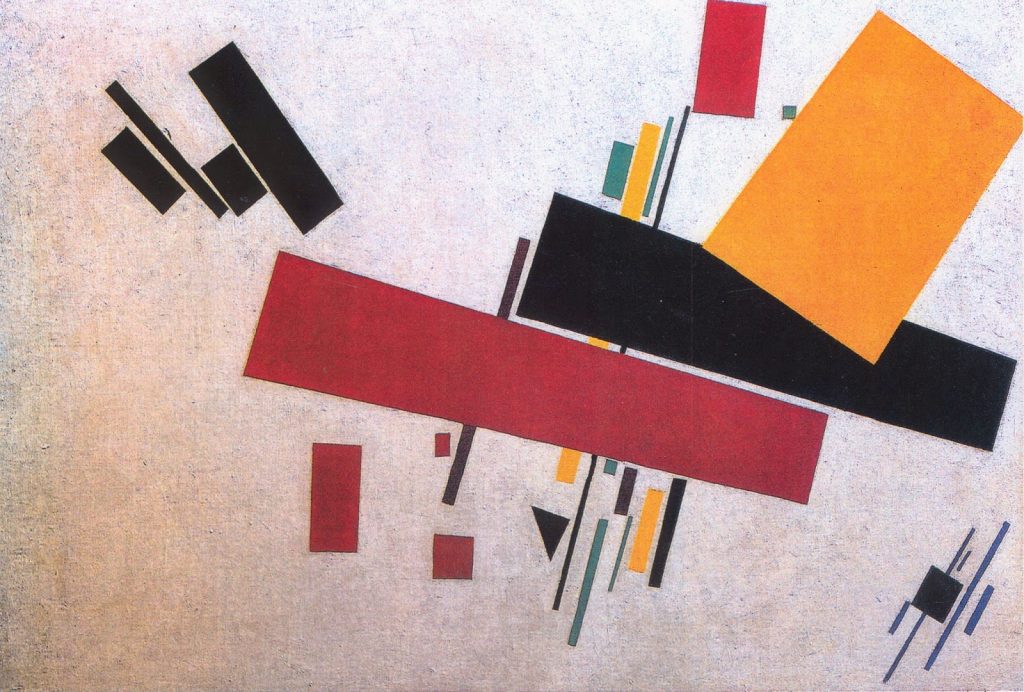

At the end of the 1980s, as perestroika took hold in the USSR, the history of the Russian avant-garde ceased to be a banned topic. This was reflected in a series of exhibitions on Kazimir Malevich, Wassily Kandinsky, Lyubov Popova and Pavel Filonov, as well as in the appearance of new research on the subject. The writing of Nikolai Khardzhiev, the leading specialist on the Russian avant-garde at the time, was particularly influential. In 1976, Khardzhiev had succeeded in publishing a collection of articles and documents entitled Towards a History of the Russian Avant-garde, which appeared in Stockholm. For the first time, his book offered an analysis of Kazimir Malevich’s autobiographical comments on the icon and concluded that: ‘At the end of 1912, Malevich completed a series of works, in which the traditions of early Russian art and folk primitivism intersect with “metallic” forms derived from Cubism’.

Dynamic Suprematism No 57 by Kazimir Malevich (1916). Photo by Arturo García from Flickr

A significant amount of material in Khardzhiev’s personal archive also confirms the view that Russian Cubo-Futurism was influenced by iconography. Khardzhiev knew many avant-garde artists personally, and at the beginning of the 1930s, while working on his History of Russian Futurism, he asked Malevich to write a memoir for his archive. In his autobiographical notes, Malevich openly acknowledged the influence of the icon on his work: ‘Icons made a strong impression on me, despite my naturalistic training and the way this defined my responses to the natural world. For me, icons seemed to reveal the Russian people as an entity, a whole with an emotional creativity of its own.’4

In 1995, Khardzhiev gave an interview to the Russian journal Zerkalo, in which he emphasized once again the significance of the icon for understanding the language of the Russian avant-garde and its specifically national features:

The art of the avant-garde was international, but there was nevertheless a national emphasis. There was such a thing as Russian primitivism – and this is not widely acknowledged in the West. Take Larionov – his work is primitivist: consider a Russian popular print or an icon … The icon is unbelievably monumental. The Russians followed the Greek tradition, but they created their own iconography … The icon and primitivism transformed western artistic influences, their effects confronted Cubism and, as a result, a new form of Russian art appeared – not imitative, but unique and original.5

Later, in his introductory article to the catalogue of the Malevich exhibition, shown in Leningrad, Moscow, and Amsterdam in 1988-1989, Dmitry Sarabyanov wrote: ‘To a certain extent, the Suprematist canvases Malevich created gravitated toward the icon. They “aspired to be” reflections on the nature of being, thoughts in “form and colour”.’6

The perestroika years also saw the appearance of an early article I wrote on this subject, entitled ‘The Icon in the Russian avant-garde of the 1910s and 1920s’.7 It was a short piece, but the first specialized publication to focus exclusively on the topic of ‘the icon and the avant-garde’. The article was written in response to the interest in primitivist art and Russian popular consciousness prevalent at the time. It offered an analysis of Malevich’s autobiographical notes, and the way in which they revealed elements of iconographic language in paintings by Goncharova, Larionov and other artists.

Artistic devices from another age

Costakis’ interpretation of the effect of the icon on the avant-garde is also likely to have been influenced by the American art historian Alfred Barr, who saw his collection during a visit to Moscow in 1956. Barr was the leading western specialist on the Russian avant-garde at the time and the former first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMa).

After examining the items Costakis had assembled, Barr persuaded him to focus as much as possible on abstract painting. Following the encounter, Costakis jettisoned the figurative works by representatives of the Jack of Diamonds movement, and began to collect abstract pieces by Alexander Rodchenko, Lyubov Popova, Vladimir Tatlin and other hitherto forgotten artists, as well as early works by Malevich, Kandinsky and Chagall.

In the 1950s, abstract art had become increasingly fashionable in Europe and American Abstract Expressionism was coming to dominate the art market. Barr’s favourite Russian painters were Malevich and Rodchenko. He had shown their work in his celebrated exhibition ‘Cubism and Abstract Art’, held at MoMA in 1936. Certainly, Barr appreciated the possibility of links between icons and the avant-garde works in Costakis’ collection, particularly the abstract pieces. Barr had first visited Moscow in 1928 and he had seen Ilya Ostroukhov’s private Museum of Early Russian Painting (in existence from 1911 until 1928). His love and admiration for the Russian icon cannot be in doubt.

On the basis of her detailed study of Barr’s Moscow diaries, the American scholar Sybil Kantor remarks: ‘One of the most important reasons for Barr’s trip to Russia was his desire to study medieval icons for his dissertation … In Barr’s diary, there is almost as much written about icons as there is about contemporary artworks.’

We also learn from Barr’s diary that, in addition to Malevich, Rodchenko and the constructivists, he developed an interest in the paintings of Larionov, Chagall and Goncharova: ‘Barr wanted to establish links between the work of these artists living in Paris at the time, and the tradition of icon-painting.’8 In other words, Barr’s Moscow diary, as well as letters and articles written in this period, indicate that he was the first western researcher to highlight the connection between icons and the avant-garde.

This context helps clarify the remarks in Camilla Gray’s classic book The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863–1922, concerning the influence of Russian folk art and icons on the work of Larionov and Goncharova. Gray had consulted Barr and seen Costakis’ collection. She also had access to the store-rooms at the Tretyakov Gallery and the Russian Museum, where she familiarized herself with medieval Russian painting and works by Russian avant-garde artists, banned from public view at the time. In her book, Gray concludes that a rethinking of Russian icon-painting techniques and elements of folk ornament constituted ‘the major independent contribution’ Goncharova made to Russian avant-garde art.9

Contemporary scholarship has touched on many aspects of this topic, from the poetics of language and formalist art theory to political, ideological, and philosophical analyses of links between the icon and the avant-garde.10 The subject became the theme of a special exhibition held at the Museum of Icons in Frankfurt and at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki in 2004 (in 2017 renamed the Museum of Modern Art-Costakis Collection). The show was entitled ‘When Chagall Learned to Fly: From Icon to Avant-Garde’ and publicized as follows: ‘This large-scale exhibition on Russian avant-garde artists, Russian icons and Lubok is a co-production between the SMCA and the Ikonen-Museum in Frankfurt. It explores the spiritual and primitivist sources of European modernist inspirations, stressing the Byzantine influences on Russian avant-garde art and its relations with popular prints (lubki).’11

Alongside all this analysis and scrutiny, the history of Costakis’ collection of icons and avant-garde paintings still awaits the serious academic attention it deserves.

In 1977 Costakis left the USSR for Greece, after donating the better part of his collection to the State Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow. The remaining items he had assembled came to serve as the initial collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Thessaloniki. See: George Costakis, Departure from the USSR Allowed… [Vyezd iz SSSR razreshit’], State Tretyakov Gallery, 2014.

G. Costakis, Collector [Kollektsioner], Iskusstvo XXI vek, 2015, 197-199. See also: Peter Roberts, George Costakis: A Russian life in art, Carleton University Press, 1994, xi.

Nikolai Khardzhiev (1903-1996); Dmitry Sarabyanov (1923-201); Alfred Barr (1902-1981). Barr was the first director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMa), 1929-1943.

N. Khardzhiev, Towards a History of the Russian Avant-garde [K istorii russkogo avangarda], Hylaea Prints, 1976, 118-119.

Zerkalo, 131/1995.

D.V. Sarabyanov, “Malevich and Art in the First Third of the Twentieth Century” [K.S. Malevich i iskusstvo pervoy treti XX veka] in exhib. cat., Kazimir Malevich 1878-1935, Stedelijk Museum, 1988, 71.

O. Tarasov, “The Icon in the Russian Avant-garde of the 1910s-20s” [Ikona v russkom avangarde 1910-1920-kh godov], Iskusstvo, 1/1992.

Sybil Gordon Kantor, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. and the Intellectual Origins of the Museum of Modern Art, MIT Press, 2002; https://www.labirint.ru/books/705637/

Camilla Gray, The Great Experiment: Russian Art 1863-1922, Harry N. Abrams Inc., 1962, 97, 100.

J. Bowlt, “Orthodoxy and the Avant-garde: Sacred images in the work of Goncharova, Malevich, and their contemporaries” in Milos M. Velimirovic and Willian C. Brumfield (eds.), Christianity and the Arts in Russia, Cambridge University Press, 1991; Oleg Tarasov, Framing Russian Art: From early icons to Malevich, Reaktion Books , 2011; Oleg Tarasov, “Florensky, Malevich and the Semiotics of the Icon” [Florenskij, Malevich e la semiotica dell’icona], La Nuova Europa, 1/2002; Andrew Spira, The Avant-garde Icon: Russian avant-garde art and the icon painting tradition, Lund Humphries, 2008; Louise Hardiman and Nicola Kozicharow (eds.), Modernism and the Spiritual in Russian Art: New perspectives, Open Book Publishers, 2017; Clemena Antonova, “The Icon and the Visual Arts during the Russian Religious Renaissance” in Caryl Emerson, George Pattison, and Randall A. Poole (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Russian Religious Thought, Oxford University Press, 2020.

Published 16 April 2021

Original in Russian

Translated by

Maria Raycheva

First published by Eurozine

© Oleg Tarasov / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

Transborder repression

Index on Censorship 1/2024

Political exiles living in fear: how the Kremlin’s repressive machinery operates far beyond Russia’s borders; why Turkey is no longer a safe haven for foreign dissidents; and the ways new technologies are facilitating transnational repression.

Georgia’s ‘March for Europe’ protests express deep polarization in the country over the current government’s pro-Russian course. The return of Moscow-friendly oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili to official politics signalled the beginning of an election campaign whose outcome will decide Georgia’s democratic future.