If Jesus is portrayed as fully human, can his divinity be rescued from the manifestation of what is visibly ‘all-too-human’? Christ’s depiction in Dostoevsky’s novel ‘The Idiot’ creates layered religious, historiographical and artistic readings.

Much of The Idiot was written while Dostoevsky and his wife were living in Florence, just a stone’s throw away from the Pitti Palace, where the writer often went to see and to admire the paintings that adorned its walls, singling out Raphael’s Madonna della Seggiola for special mention.1 It is very probably no coincidence that visual images play a prominent role in The Idiot.2 Early on in the narrative, Prince Myshkin, the eponymous ‘idiot’, sees a photograph of the beautiful Anastasia Phillipovna that makes an extraordinary impression on him and generates a fascination that will end with her death and his madness.3 But insofar as Anastasia Phillipovna is the epitome of human beauty in the world of the novel, this photograph can also serve as a visual aide to the saying attributed to the Prince, that ‘beauty will save the world’.4 Later, he is confronted with an image of a very different kind — Hans Holbein’s 1520-22 painting of the dead Christ, shown with unflinching realism and reportedly using the body of a suicide as model. It is a Christ stripped of the beauty that bourgeois taste regarded as an essential attribute of his humanity and, in its unambiguous, mortality, devoid also of divinity. On first seeing it, Myshkin comments that a man could lose his faith looking at such a picture5 and, later, the despairing young nihilist, Hippolit, declares that just this picture reveals Christ’s powerlessness in face of the impersonal forces of nature and the necessity of death that awaits every living being. It is, Hippolit suggests, an image that renders faith in resurrection impossible.6

Le Christ mort au tombeau by Hans Holbein (in Kunstmuseum, Bâle) Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Flickr

These two images can be seen as establishing the visual parameters for a complex interplay of the themes of beauty, death, and divinity that run through the novel as a whole and that go a long way to structuring the conceptual — and religious — drama at its heart. This drama is also, crucially, at the centre of then contemporary European debate about Christ and about the representation of Christ. But these are not the only images that contribute to Dostoevsky’s take on that debate. It has been suggested that the opening description of Myshkin is modelled on the canonical icon of Christ in Orthodox tradition and much of the novel’s theological force has to do with the eclipse of Myshkin’s icon-like identity in the encounter with a modern Russia in the grip of a capitalist revolution.7 On his arrival in St Petersburg from the West, Myshkin goes to call on his distant relative, Mme Epanchina ( it is in her husband’s office that he sees the photograph of Anastasia Phillipovna). Mme Epanchina’s oldest daughter Adelaida is a keen amateur landscape painter and over breakfast Myshkin rather inappropriately suggests that the face of a man in the moment of being guillotined might make a suitable subject for her painting.8 And, finally, there is an imaginary painting of Christ that Anastasia Phillipovna ‘paints’ in one of her letters to Aglaia Epanchina to whom, by this point, Myshkin has become engaged. It is this ‘painting’ that is the main focus of this paper, in part because it has been under-discussed in secondary literature in comparison with Anastasia’s photograph and Holbein’s dead Christ but also because it makes an important contribution to the debate about Christ and about how to represent Christ that, as we have seen, is central to the religious questions at issue in the novel.9

This picture is, of course, painted in words and not an actual painting, but Anastasia Phillipovna describes it as if it were a painting and she clearly wants Aglaia too to see it that way. Dostoevsky thus invites readers too to imagine it as a picture they might see in a gallery. Anastasia Phillipovna depicts Christ as sitting, alone, accompanied only by a child, on whose head he ‘unconsciously’ rests his hand, while ‘looking into the distance at the horizon; thought, great as the world, dwells in His eyes. His face is sorrowful’. The child looks up at him, the sun is setting.10

On first reading, the portrait might not seem very unusual. It is the kind of portrait that we have become rather used to. Christ sitting with children is a subject familiar from innumerable popular Christian books and devotional pictures. Yet in the 1860s images of Christ sitting and of Christ sitting with children were both equally innovative, having relatively few precedents in earlier iconography.

As regards Christ sitting, this is mostly limited to a clearly defined set of images that usually emphasize his power and authority or have a clear liturgical reference, most obviously in the image of the Pancrator, but also, e.g., at the Last Supper or speaking with the Samaritan Woman at the Well. Similarly, pre-modern traditions mostly neglected images of Christ with children, although this begins to change in the Renaissance. Nevertheless, even when the theme of Christ blessing the children (Mt. 19.14) is taken up by the older Masters, these are mostly heavily-populated crowd scenes, in which the interactions amongst Christ and the adults present is the main story. Examples here would include Adam van Noort’s painting of Christ Blessing the Little Children (early 17th century), Van Dyck’s (1618-20) painting Let the Children Come to Me.

Painting by Adam van Noort, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons / Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie

Unsurprisingly, the theme becomes much more common with the rise of romanticism and a new more positive evaluation of childhood and the idea that children had a special affinity with the divine, with notable examples from Benjamin West, William Blake, and Charles Lock Eastlake and, by the mid-Victorian era, it had become a widespread and popular topic .Unlike in earlier representations, Christ is now to be seen alone with varying numbers of children, unaccompanied by a crowd of mothers and disciples. This tendency becomes especially prominent in illustrated Bible stories specifically for children—another phenomenon of the nineteenth century.

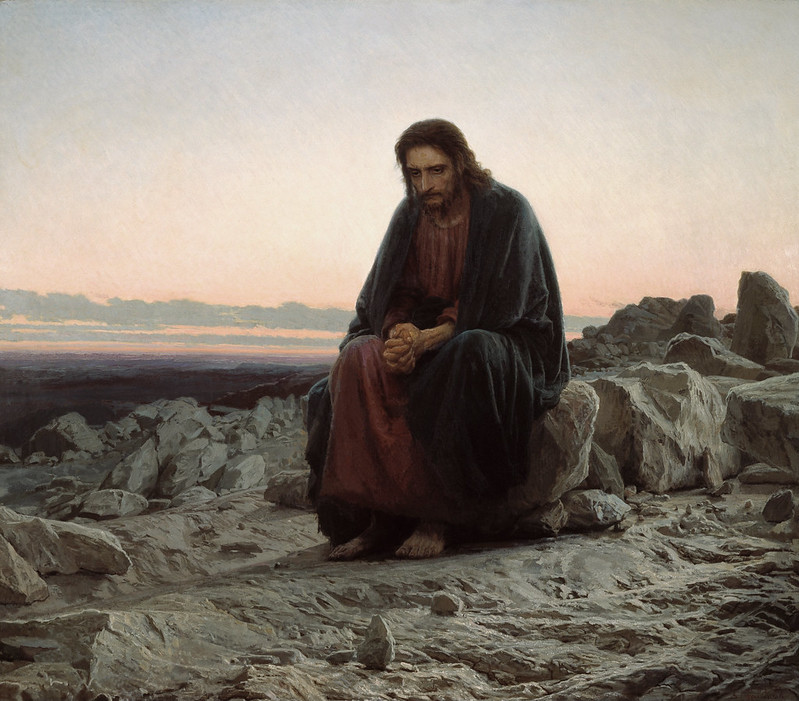

Similarly, Christ now begins to appear sitting, alone, thinking, perhaps even somewhat melancholic, a Man of Sorrows but without the physical marks of the passion. Examples include Dostoevsky’s Russian contemporary Ivan Kramskoy’s Christ in the Desert, a work first exhibited in 1872 (and again in 1873) but which he had been working on through much of the 1860s and therefore contemporary with Dostoevsky’s own work on The Idiot.

In a sense, the reason for the new prominence of these themes is not hard to fathom. It reflects a turn to the human Jesus and a new emphasis on the role of feeling in religious life. The Christ of ecclesiastical tradition was Saviour by virtue of the ontological power of the hypostatic union, uniting divine and human in the very person of his being. It is this identity as both divine-and-human that makes it possible for his innocent suffering on the cross to be salvific rather than merely tragic. In the wake of romanticism, however, his qualification as Saviour has to do with his uniquely intense God-consciousness and his unrestricted empathy with other human beings, an empathy that extends even to their suffering and sin.

At the same time, and for related reasons, the theological approach to Christ became increasingly dominated by historical research, as in the nineteenth century ‘Lives of Jesus’ movement. Here the idea was that the reality of Christ’s life was less to do with his metaphysical qualifications but with the actuality of his life in the world, an actuality that could (many hoped) be retrieved through historical research. In some cases (David Friedrich Strauss was a prime example) this was part of an overtly anti-Christian or at least anti-ecclesiastical and anti-dogmatic tendency; in others (as in Schleiermacher) it was an attempt to demonstrate how Christ’s personality made him a suitable mediator between divine and human. In many cases, the emphasis on Christ’s uniquely universal empathy and historical enquiry could be fused, as in one of the most influential of all the nineteenth century lives of Jesus, that of Ernest Renan.

Renan describes Jesus’s religion as ‘a religion without priests and without external practices, resting entirely on the feelings of the heart, on the imitation of God, on the immediate rapport of [human] consciousness with the heavenly Father’.11 Renan’s characteristically 19th century bourgeois assumptions led him to see women as being especially susceptible to ‘the feelings of the heart’ and it was therefore no surprise that ‘women received him eagerly’.12 ‘[W]omen and children adored him’13 and

… the nascent religion was thus in many respects a movement of women and children … He missed no occasion for repeating that children are sacred beings, that the Kingdom of God belongs to children, that we must become as children in order to enter it, that we must receive it as a child, and that the Father conceals his secrets from the wise and reveals them to the little one. He almost conflates the idea of discipleship with that of being a child … It was in effect childhood, in its divine spontaneity, in its naïve bursts of joy, that would take possession of the earth.14

Renan too describes for us Jesus sitting alone, on the Mount of Olives, looking out over Jerusalem (which, he tells us, Jesus did often), plunged in a ‘profound mood of sadness’.15

Painting by Anthony van Dyck, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

How do these themes resonate with the action and personalities of The Idiot? Clearly, Anastasia Phillipovna’s ‘portrait’ of Christ lives in the atmosphere of Renan’s and similar humanist-sentimental lives of Jesus. But what does this mean for the novel’s possible contribution to the religious understanding of Christ as a whole?

The historical Lives of Jesus movement had its scandals, but the parallel moves in art also provoked bemusement and sometimes hostility, as in the case of other new developments in nineteenth century art. The novelty of this new view of Christ can be seen by reactions to Ivan Kramskoy’s painting of Christ in the wilderness. Tolstoy would later say of it that it was ‘the best Christ I know’, but many of the reactions to it were far more negative. For many this was a Christ devoid of divinity, a manifestation of historicist positivism in art. ‘Whoever he is,’ Ivan Goncharov continues, ‘he is without history, without any gifts to offer, without a gospel … [Christ] in his worldly, wretched aspect, on foot in a corner of the desert, amongst the bare stones of Palestine … where, it seems, even these stones are weeping!’16

What kenotic Christology refers to as Christ’s state of exinanition (i.e., his human state of weakness and vulnerability, emptied of his divine attributes), is thus becoming a theme of contemporary art at the time of Dostoevsky’s composition of The Idiot, paralleling to some extent the development of the historical portrayal of the life of Jesus. Both in historiography and art the same question then arises, namely, how, if Jesus is portrayed as fully human, can his divinity be rescued from the manifestation of what is visibly all-too human?

Extolling Christ’s exceptional sensitivity and empathy seems not to provide a sufficient bulwark against such a collapse. Renan’s sentimentalism, no matter how ‘beautiful’, offers little ultimate protection against nihilism. This is a beauty that can neither save the world nor turn it upside down. The sitting Christ, absorbed in brooding thoughts and given over to melancholy, seems to be a Christ who is in the process of becoming all-too human. In this regard, it is noteworthy that where Renan’s Christ goes alone to look out over Jerusalem at sunrise, Anastasia Phillipovna’s Christ is pictured at sunset. Her portrait reveals the shadow side of Renan’s optimism. For her, the light is fading, as natural light always must.

But what does this tell us about Dostoevsky’s novel? Firstly, it underlines the contemporaneity of Dostoevsky’s visual vocabulary deployed in the novel. Not only is this one of the first novels in which a photograph (the photographic portrait of Anastasia Phillipovna) plays a major role, but the image of the sitting Christ, accompanied only by a child, reflects contemporary developments in religious art that are also further connected with contemporary historiography. Holbein’s dead Christ is, of course, a picture from an earlier age. However, on the one hand, it offers a ne plus ultra of the humanizing approach to Jesus and, on the other (as I have argued elsewhere) it is a theme we also find in Manet’s Dead Christ with Angels, exhibited alongside his better-known Olympia in the same year that The Idiot was published.17 Like Kramskoy’s painting, this was seen by many critics as sacrilegious and an affront to faith by virtue of the elimination of all elements of beauty and conventional sacrality. Visually, as well as in literary terms, Dostoevsky is entirely in synchronization with the decisive movements of the visual culture of his time.

In fact, commenting in 1873 on Nicholas Gé’s Mystic Night (which, as we have seen, also attracted Goncharov’s attention), Dostoevsky showed himself to be alert to the risks of a one-sidedly humanizing and sentimental approach to Christ in art. In a review published in The Citizen he writes:

Look attentively: this is an ordinary quarrel among most ordinary men. Here Christ is sitting, but is it really Christ? This may be a very kind young man, quite grieved by the altercation with Judas, who is standing right there and putting on his garb, ready to go and make his denunciation, but it is not the Christ we know. The Master is surrounded by His friends who hasten to comfort Him, but the question is: where are the succeeding eighteen centuries of Christianity, and what have these to do with the matter? How is it conceivable that out of the commonplace dispute of such ordinary men who had come together for supper, as this is portrayed by Mr. Gué [sic], something so colossal could have emerged?18

Photo by Yulia Mi from Flickr Christ in the desert, 187, Oil on canvas, The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moskow (RU)

Secondly, setting Nastasya’s portrait of Christ in an art-historical context may not directly solve the question as to whether Myshkin is to be regarded as some kind of Christ-figure (and, if so, what kind) but it does illuminate how Anastasia Phillipovna sees him. We know that she reads much and is given to speculative ideas, and it is therefore not at all surprising that her vision of Christ and of Myshkin as Christ is a vision taken from contemporary, humanist, Western sources, a sentimental Christ whose power to save is, at best, fragile. In this way, whether or not we are to read Dostoevsky’s portrayal of Myshkin as a Christ-figure, he is a Christ-figure, albeit a very particular kind of Christ-figure, for her. Whether we can go further and say with Evgeny Pavlovitch (a character whose standpoint is that of enlightened common-sense) that Myshkin’s own understanding of the Christian requirement is drawn from those same Western sources and that his love of Russia and Christian charity is an idealism, the product of ‘intellectual convictions’ that he has mistakenly believed were ‘real, innate, intuitive convictions’, is another question.19 To the extent that this is so, however, we can say that Anastasia Phillipovna is not mistaken in seeing in him an instantiation of her own Christ-idea and we might even discern a deep collusion between them in sharing the fantasy of such a sentimental salvation. In any case, to the extent that Anastasia Phillipovna places her own hope of salvation in such a Christ-figure, it is doomed to fail.

There is one further iconographical intertext that is worth exploring in connection with Anastasia Phillipovna’s ‘portrait’, although it is not expressly mentioned. What is mentioned—Evgeny Pavlovitch mentions it—is that Myshkin’s relation to her might be seen as mirroring the gospel story of the woman taken in adultery and protected by Christ from being stoned to death (an association reinforced by the story Myshkin himself tells of the outcast Marie he had rescued from ostracism in the little Swiss village where he had lived before the start of the novel’s action).20 This woman has long been conflated in Christian tradition with Mary Magdalene who, in turn, has been conflated with Mary, the sister of Martha. She, is of course, a woman described in the gospels as sitting at the feet of Jesus, silently listening to his words in one of the few non-hieratic scenes in which we usually see Jesus himself seated. Famously, she is commended as the one who has taken the better part. If such an allusion lies in the background of Anastasia Phillipovna’s portrait, it reinforces, albeit subtly, the associations between Myshkin/Christ and Anastasia Phillipovna/woman-taken-in-adultery, underlining that it is not Aglaia that we are to see in the figure of the silent child, but Anastasia Phillipovna herself. This would imply that her deepest hope is, through Myshkin, to sit at the feet of Christ, listening to his word, taking the better part. But if this is her hope, then it is well-hidden, screened not only by the substitution of Aglaia for herself but also by the sentimental positivism of nineteenth century historicism that comes to expression in her portrait of a melancholy Christ contemplating the light of a setting sun. In this way, it may not only be her psychological injuries that make her incapable of accepting the forgiveness that Myshkin offers, it may also be her—and the age’s—misconception of Christ that gets in the way. This, clearly, makes the issue less individual and less psychological. Arguably, it also makes it more tragic in a classical sense. This is because her fate is that of a whole world of values that, in this historical moment, is descending into the impending darkness. Yet—even if Dostoevsky himself does not say this—there might remain a chance, however slender, that this ‘human all-too human’ Christ retains a memory of another light and, with that memory, the hope that the values of this present age are not the sole values by which we and the world are to be judged.

See F. M. Dostoevsky, Pisma, Vol. 20 in Polnoe Sobranie Sochineniī v Tridtsati Tomakh (Leningrad: Nauka, 1985)

However, there are allusions to Raphael’s Sistine Madonna in both The Devils and The Brothers Karamazov. Dostoevsky saw the painting in Dresden and was exceptionally moved by it. Later his wife would arrange for him to be given a large photographic reproduction that he hung in his study.

It is worth adding here that this is one of the first times that a photograph plays an important role in a major work of fiction, a fact that supports the argument made in this paper for the thoroughly contemporary nature of Dostoevsky’s visual aesthetic.

We never hear the Prince say this directly, but it is quoted in his presence by the young nihiist Ippolit. Adelaida Epanchina says it is a beauty that could overturn the world and later it will also be alluded to by Aglaia Epanchina. Ippolit’s statement is at F. M. Dostoevsky, The Idiot, trans C. Garnett (New York: Macmillan, 1951), p. 373/ F. M. Dostoevski, Idiot, vol. 8 in Polnoe Sobranie Sochineniī v Tridtsati Tomakh (Leningrad: Nauka, 1973), pp. 317. Taken at face value, the saying is sometimes used as key to an overall interpretation of Dostoevsky’s theological intentions, as e.g., in Bruno Forte, The Portal of Beauty. Towards a Theology of Aesthetics , trans D. Glenday and P. McPartlan (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), pp. 43-52.

Dostoevsky, The Idiot (1951), p. 211/ Idiot (1973), p. 181.

Dostoevsky, The Idiot (1951), pp. 399-400/ Idiot (1973), pp. 338-9. This image is much commented on in secondary literature.

See, e.g., Irina Kirillova, Obraz Khrista v tvorchestve Dostoevskogo. Razmyshleniia (Mosocw: Tsentr knigi VGBIL im. M. N. Rudomino, 2010), 82-102.

It has been suggested that Hans Fries, The Beheading of John the Baptist, which Dostoevsky is likely to have seen in Basel, is also being alluded to here.

Even though her classical work of Dostoevsky commentary Dostoevsky and the Idiot discusses both Myshkin’s identity as a Christ figure and the correspondence between Nastasia and Aglaia, Robin Feuer Miller does not mention this particular word-portrait. See Robin Feuer Miller Dostoevky and The Idiot (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1981).

See Dostoevsky, The Idiot (1951) p. 446/ Idiot (1973), pp. 379-80.

Ernest Renan, Vie de Jésus (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 1938), p. 58.

Ibid., p. 104.

Ibid., p. 134.

Ibid., pp. 136-7.

Ibid., p 214.

Ibid. In the same essay, Goncharov also commented on Nikolai Ge’s Mystic Night (Тайная вечеря) of 1863, showing the last supper at the moment of Judas’s departure. Again, this is a Christ who seems, humanly, on the point of defeat. See the discussion below of Dostoevsky’s response to this painting.

For discussion see George Pattison, ‘Art, Modernity and the Death of God in idem, Crucifixions and Resurrections of the Image (London: SCM Press, 2009), pp. 21-44, especially 24-36.

F. M. Dostoeivsky, The Diary of a Writer, trans. Boris Brasol (Haslemere: Ianmead, 1984), p. 84/ F. M. Dostoevsky, Dnevnik Pisatelia in Polnoe Sobranie Sochineniī v Tridtsati Tomakh, vol. 21 (Leningrad: Nauka, 1980), pp. 76-7.

F. M. Dostoevsky, The Idiot, p. 569/ Idiot, p. 481.

Ibid./Ibid.

Published 15 December 2021

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by The Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) © George Pattison / The Institute for Human Sciences (IWM) / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTIn collaboration with

In focal points

Newsletter

Subscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Related Articles

From Helsinki to full-scale invasion

Russia, European security and the OSCE

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and its denial of rights at home, are precisely the kind of development that the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe was set up to prevent. So why has the OSCE failed to fulfil its purpose?

Two opposing interpretations of 1945 form the ideological core of today’s confrontation between Russia and the states of central and eastern Europe. Both are reactions to the collapse of the Cold War order.