The state unconscious

K24 November–December 2025

Horizons of the Turkish novel; dissident disappointments; communists real and false; the feminine street.

The anti-EU sentiment emerging from Central Europe today suggests that little remains of the ‘arch-Europeanism’ Milan Kundera once ascribed to the region. But was there something inherent to Kundera’s concept of Central Europe that explains the logic of contemporary Polish, Hungarian, Czech and Slovak nationalism?

In November 1983, the French magazine Le Débat published an essay by the Czech writer Milan Kundera entitled ‘A kidnapped West: The tragedy of Central Europe’.1 An English translation appeared in The New York Review of Books in April 1984, sparking a debate on both sides of the Atlantic. The Polish version, published in the May edition of Zeszyty Literackie,2 was accompanied by criticisms of Kundera’s argument, translated from Hungarian, French and English. The impact of ‘A Kidnapped West’ on debates on Central Europe in the following years was comparable to that of Francis Fukuyama’s essay ‘The End of History?’ on debates on global politics.3

Kundera outlined the desperate dilemma faced by Poles, Hungarians and Czechs (there was no mention of Slovaks) following the resolutions passed at the 1945 Yalta Conference, which had left their countries under Soviet domination. The populations of all three countries rebelled repeatedly against the communist regimes. There were uprisings in Hungary and Poland in 1956, in Czechoslovakia and Poland in 1968, and in Poland in 1970, 1976 and 1980. These insurgencies against violent repression took strength from a sense of cultural heritage.

The essay set up a dichotomy between ‘the West’, epitomised by Central Europe, with its array of nationalities, cultures, faiths and languages, and with its principle of conflict resolution without force, and Russia, an ‘anti-West’ whose identity was based on uniformity through force. According to Kundera,

Central Europe longed to be a condensed version of Europe itself in all its cultural variety, a small arch-European Europe, a reduced model of Europe made up of nations conceived according to one rule: the greatest variety within the smallest space. How could Central Europe not be horrified facing a Russia founded on the opposite principle: the smallest variety within the greatest space?4

In prizing apart East and West and exposing a forgotten space between, Kundera achieved something extraordinary. He introduced into European discourse the image of a region in which culture determined identity, an extra-political narrative that explained resistance to the Soviet Union yet transcended national identities. Simultaneously, he provided the basis for Central European claims towards ‘the West’. Soviet Russia had colonized spaces that were culturally alien to it, Kundera argued. At the end of World War II, however, Western Europe had betrayed her ‘younger sister’ to protect its own security and affluence.5

Despite these simplifications (or perhaps because of them), Kundera succeeded in transforming geopolitics into geo-poetics. Throughout the post-war era, Europe had been paralysed by ideology. Just as each side recognized the territorial integrity of the other ideological bloc, so it recognized the integrity of the other’s narratives. Kundera provocatively suggested that the European map had emerged from discourse as much as politics.

Kundera’s essay found numerous critics.6 Some, like Adam Zagajewski, questioned the image of a homogenous Russia and Russian culture; others disputed Kundera’s suggestion that Central Europe had previously been free from oppression.7 Czesław Miłosz suggested that the region should incorporate the Baltic states.8 But despite disagreements about Central Europe’s scope and identity, by the late 1980s Kundera’s concept of ‘Central Europe’ had become a source of inspiration.9 The facticity of his narrative was not disputed, nor was its usefulness in building the future Europe.10 Kundera’s aim was widely shared: the identification of the Centre with the West in the cultural and geographical map of Europe. Once this had been achieved, history would reach its conclusion.

After the states of Central Europe had regained their independence, events unfolded according to Kundera’s script. In 1991, four Central European countries – Poland, Hungary and Czechoslovakia (dissolved into Czechia and Slovakia in 1993) – formed the Visegrád Group. Their alliance was based on the notion of a shared cultural tradition. In 1992, they signed a trade pact known as the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA). This was the first international accord ever to include the term ‘Central European’ as a political category. In 1994, the states of Central Europe applied for membership of the European Union; in 2003, they signed the EU Accession Treaty; and, in 2004, they were officially received into the EU.

Twenty years after the publication of Kundera’s essay, the geographical and cultural programme outlined in it had been implemented. The Soviet Union had lost its imperial dominance over half the continent and Central Europe had joined the West. With the region’s long-sought institutional integration into the European Union, Central Europe had finally returned to its roots.

But it turned out that the ending was also the beginning of an unexpected conflict.

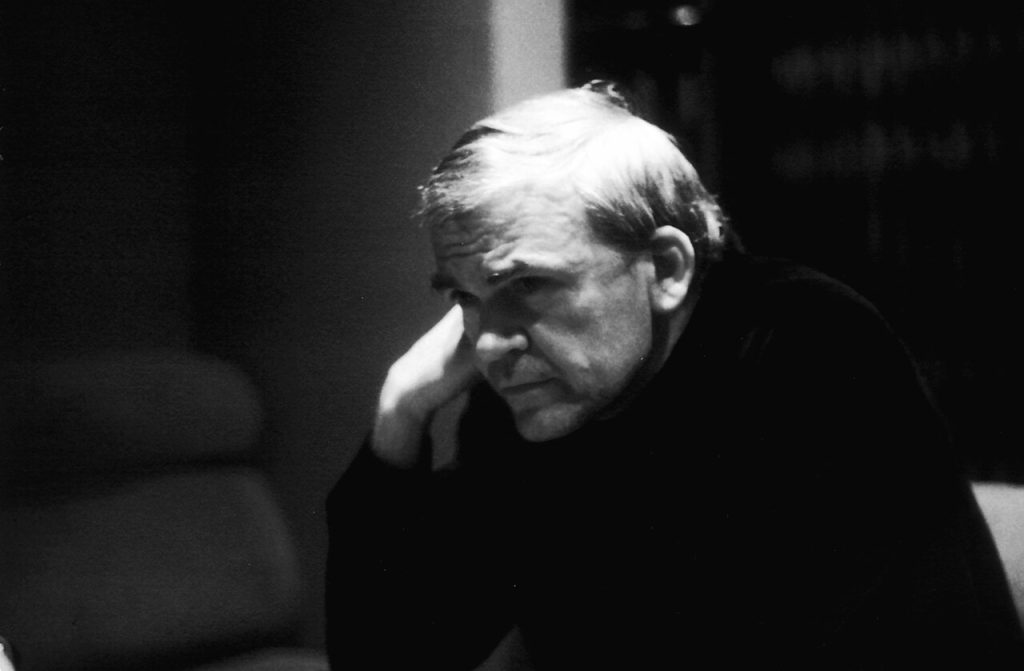

Milan Kundera in 1980. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Two more decades later, the debate around Kundera’s essay needs to be reopened. Without doubt, the essay helps us understand how states that had relatively little in common came to bond so rapidly in an aspiration towards the West. It also explains what the myth of ‘a return to Europe’ offered the states of Central Europe. As they saw it, they were not being ‘accepted’ but were reclaiming their rightful place. This was a narrative that restored to them their dignity.

But if Kundera’s essay is to be anything more than a source of nostalgia, it must be tested against the present. That means we must confront it with subsequent historical developments, especially those of the last decade, and ask a series of questions. Above all, why are the nationalist parties in Poland and Hungary, and increasingly in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, seeking to undermine the EU twenty years after joining it? Why are these countries seen as being particularly intolerant of their minorities? Why have women not been granted reproductive rights in Poland and Hungary? Why are these states sabotaging the EU’s plans for a green transition?

A critical reading of Kundera’s article must begin by asking what the author meant by ‘Central Europe’. He clearly used the term to refer to just three states: Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, which he viewed as a unit rather than as representing all the states lying between East and West. He vaguely associated Central Europe with the Austro-Hungarian empire, as well as with regions occupied by the Soviet Union after World War II. Yet neither of these territorial constructs corresponded exactly with Kundera’s definition of Central Europe. This game with history and geography allowed Kundera considerable freedom, but also involved a certain cartographical laxity.

For if Kundera’s intention had been to refer to the Habsburg state as it existed between 1867 and 1918, he would have had to include not only Poland, Czechia, Slovakia and Hungary, but also Ukraine, Romania, Croatia, Serbia and Slovenia. His phrase ‘maximum diversity within the smallest possible space’ would have had to apply to a constellation of 19 nations and ethnic groups, 52 million people, and 670,000 square kilometres of land. While the vast ethnic, linguistic, religious and cultural diversity of the Habsburg Empire was indeed one of its defining characteristics, the way Kundera carved out three states from the historical map was completely arbitrary. What could his reasons have been?

Kundera could not refer to the Habsburg state as a whole because not all the nationalities represented within it had accepted Austria-Hungary as a political entity. Nor could he ignore the nationalisms of the time, which were precisely what had broken up the unity of Central Europe. And so he invoked the memory of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, while at the same time focusing exclusively on the Poles, Czechs and Hungarians, whose longing to belong to Europe was, unlike the other parts the Empire, greater than their desire for national autonomy. This allowed him to dismiss a vast expanse of Central Europe while identifying his chosen area as the ‘real’ centre.

For Kundera, the common ground uniting the three countries was culture, which he described as an expression of group identity and ‘living value around which all people rally’. His point was that European culture – created by and inherited from the nations of Central Europe – was the foundation for the belonging felt by Poles, Czechs and Hungarians. It was a language through which they could understand their identity and express their resistance to oppression from the East.

Viewed thus, culture was less a canon of works and particular artists, or a store of styles and conventions, than an everyday collective practice. In Central Europe, according to Kundera, culture bound entire societies. It was created as an expression of common aspiration and received as such by everyone. Central European culture was not elitist but a direct expression of the life of society.

But whose culture was it really? Who had real knowledge of it? Who cultivated and created it? Kundera’s examples were taken from the canon of modernist high culture. He referred to Schönberg, Bartók and the Prague Structuralists, to Kafka, Musil, Broch and Hašek, to Gombrowicz, Schulz and Witkiewicz… The readers of the essay – intellectuals, historians, dissidents – would have recognized ‘their own’ artists and acknowledged them as the real representatives of Central Europe. Yet what social group do listeners of twelve-tone music belong? Who knew the work of the Prague Structuralists, or the novels of Musil?

In Central Europe, Kundera wrote, culture and the people were one. Yet in his essay, ‘the people’ were the artistic elites and the urban intelligentsia. In the early twentieth century, this social group had embraced Modernism, introducing it into education and securing its masterpieces a lasting place in the canon. There is no doubt that Kafka, Musil, Gombrowicz and the others all deserved to be there. But Hašek apart, the various canons were short of any representatives of the ‘culture of the people’ to which Kundera referred.

As already mentioned, the essay isolated three successor states of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, attributing to them the capacity to overcome their nationalist inclinations and to integrate into Europe. But though formed in the name of entire nations, Kundera’s concept of Central Europe reflected class boundaries. Much like the aesthetics of Kant, it belonged to the intelligentsia and the bourgeoisie. The concept was conceived on the basis of the culture of this class and addressed to it, as representative of society as a whole.

Kundera’s essay was thus reductive on two levels. First, it suggested that the violent struggle for national and state self-determination was over and that the three states had brought forth an idea that unified Central Europe. Second, it treated the urban intelligentsia as the class that set the mark for citizenship and cultural competency. Kundera disregarded not just the ‘Central European’ states’ aspirations towards national sovereignty, but also the internal social conflicts within them. In these gaps, and in the attempt to obscure them with idealisations, lie the roots of many of the troubles we find in Central Europe today.

The most compelling proof for Kundera that Central European societies had maintained their European identity was their willingness to sacrifice their lives for Europe and European culture. The Hungarians, Poles and Czechoslovaks who had defied Soviet Russia were, he believed, the custodians of the ‘Central European idea’. A place in Central Europe was something that had to be earned.

This notion of Central European exceptionality, introduced by Kundera into public discourse, underpinned the revival of the region in the 1990s. Later, however, it led to an anti-European backlash in all four Central European states. In Poland, the anti-European tendency was checked but by no means eradicated by the election of a liberal-conservative coalition in 2023; under a rightwing government, it could return in a yet more acutely.

Obviously, Kundera cannot be blamed for this. But to cling to the myth he played a major role in creating is bound to intensify any conflict between Central Europe and the European Union. Kundera depicted Central Europe as being more ‘European’ than Europe, as possessing a Europeanness that was more egalitarian and self-sacrificing. According to this bourgeois myth, the three chosen nations – or, more specifically, their leaders – had the privilege of defining their European identity on the basis of on ‘authentic culture’.

Key to this concept of European identity is not the language of law, or respect for democratic process, or an aspiration towards social equality. Instead, it is a cultural mission. This allows the Hungarian prime minister to speak of his country’s ‘moral superiority’ over a ‘decadent West’, and the former Polish president to refer to the European Union as an ‘imagined community without much significance for Poland’. It provides the basis on which to accuse the West of exaggerating the principle of equality before the law, or those who appeal to the European Court of Justice of betraying their country.

On the face of it, such claims would seem to directly contradict Kundera. But the road from Kundera’s arch-Europeanism to the anti-Europeanism widespread throughout Central Europe today runs through the gateway of perceived exceptionality. In Central Europe, Kundera’s essay produced a characteristic mix of feelings of inferiority and superiority. Central Europe had been humiliated by subordination to the USSR, he argued, yet the region’s significance had also been elevated above the West’s, which was no longer the ‘real’ Europe. Today, this kind of thinking leads politicians in Poland, Hungary and Slovakia to think they can invoke the cultural values of Central Europe in order to dictate their terms to Brussels.

Kundera’s idealisation of Central Europe is the antithesis of István Bibó’s 1946 essay ‘The misery of small European states’.11 The texts differ in almost every way: range, coherency and historical detail. Their premises are also fundamentally opposed. For Kundera, Central Europe offered the opportunity for the revival of Europe as a single cultural unit, while according to Bibó, the region had been the world’s greatest ‘hotbed of conflict’ since the 19th century. All that the two authors agreed on was that the formation of Central Europe was determined by a fear that it would vanish from the map.

Each drew different conclusions from this. Bibó wrote that, between the wars, an ‘existential fear for the survival of the community’ had driven the Poles, Hungarians and Czechoslovaks to place the national cause above the law. This had led to violations of rule of law, censorship and constraints on democratic rights:

There appeared different, changeable forms of falsifying and corrupting democracy, ranging from methods that were often unconscious to the crudest possible measures: the exploitation of universal suffrage to impede the development of democracy, an unhealthy system of coalitions and compromises based on unclear criteria … and, finally, coups and temporary dictatorships.12

As a result, Central Europe had produced a succession of ‘false realist’ politicians who provoked in society a ‘hysteria’ marked by lack of ‘balance between things that exist, and things that are possible and desirable’. In other words: a conviction of being right in what one wanted and deserving of what one demanded.

The fear of ‘disappearing from the map’ also appeared in Kundera’s essay. But he gave fear a radically different character. For Bibó, fear was an affect that distorted everything, from democracy and political thought to the psychological state of society. But for Kundera, fear was transformed into the courage that provided Central Europe with its cohesion and bound it to the West. He began his essay by citing the telex message sent around the world by the director of the Hungarian Press Agency during the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, which ended with the words: ‘We are going to die for Hungary and for Europe.’

This notion of the transformation of fear into courage concealed a problem, however. For in Kundera’s scheme, courage did not lead Central Europeans to confront their own history. The events of 1989 provided an opportunity for this kind of self-exploration. But instead of revealing uncomfortable truths about Central Europe’s tolerance, its political systems and its internal inequalities, Kundera’s idealized image of Central Europe was replicated.

Kundera’s ode to Central European tolerance was only possible so long as he failed to mention the Holocaust. The Holocaust’s absence from the narrative freed him (and frees us) from any obligation to remember the mass anti-Semitism of the Poles, Czechs, Slovaks and Hungarians.13 Only through this act of collective forgetting could (and can) Central Europe enact its psychodrama of innocence on the international stage. But the performance is driven by fear of the truth. The only way to protect the lie is to resort to force – to create laws that censor the arts and sciences, to invent concepts like pre-emptive antisemitism,14 to cover up all traces of guilt, to invent histories that justify demands for reparations.

Another source of fear lay in the history of democracy in the countries of Central Europe, which according to Kundera were rooted deeply in European traditions of liberty. Yet, in the second decade of the interwar period, Poland and Hungary were authoritarian states moving rapidly towards fascism. They implemented aggressive assimilation policies towards their minorities, while resolving conflicts either by coups or by maximum security prisons.

The erasure of these forgotten ‘traditions’ means that today, the states of Central Europe are returning to their old ways while at same time invoking the exceptionality and uniqueness that Kundera attested to them. In the name of their ‘arch’ Europeanness, they seek a place in the EU that allows them ‘maximum benefit with minimum responsibility’.

But in doing so, they have been committing a form of separatist suicide. For example, in 2021, the EU Commission issued Poland a fine of one million Euros per day for the implementation of a reform passed by the PiS government in 2019 lifting judicial immunity (reduced by half in 2023 following efforts by Donal Tusk’s liberal-conservative alliance to reverse the legislation). And between 2022 and February 2024, both Poland and Hungary were unable to access EU funds distributed to countries within the framework of the National Reconstruction Plan, due to their breaches of EU rule of law conditions.15

The third source of Central European fear lies in its economic history. Why did Kundera make no attempt to align Central Europe with neighbouring regions colonised by the USSR? Why did he not take account of Romania, Albania, East Germany and Bulgaria? And what about the eastern belt of Europe: Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus and Ukraine? Why, despite pointing the finger at Soviet Russia, did he make no reference to these common experiences of communism?

The omission appears to have resulted from Kundera’s understanding of communism, which he regarded as a system of oppression and external domination that, while taking away people’s freedom, did not transform the economy, social structures or cultural practices. This allowed him to invent a story about countries that, after the Second World War, required no radical change. Yet these states had already struggled with serious difficulties between the wars. Both Poland and Hungary (not to mention Romania and Albania) bore strong vestiges of feudal structures. The developmental inequalities between urban areas and the provinces were vast. Most roads were unsurfaced and there were few bridges; industrialisation was limited, unemployment was high, and secondary education was elitist. There was mass illiteracy, policies towards ethnic minorities were harsh, and foreign policy was increasingly irrational. Only by ignoring these problems could Kundera suggest that communism – interpreted as sheer coercion – subjugated Central Europe but failed to penetrate its heart.

Contrary to Kundera’s depiction, the pre-war similarities between Central Europe states lay above all in their poverty and underdevelopment. To acknowledge this would have required him not just to abandon his idealised image of the region, but also to admit that, following the war, reforms were indispensable – albeit not looking down the barrel of a Soviet gun.

After 1989, the influence exerted by Kundera’s essay ensured that ‘the people’ of Central Europe were perceived as internally integrated and unified, bourgeois rather than working class, and urban rather than rural. Communism and poverty were disavowed in equal measure. This implied that, after 1989, the different classes and social groups within Central European society had started out under equal conditions, from positions that were evenly balanced. It was only later that it emerged that this was not the case. The consequences remain with us now in the form of a persistent wealth gap and broken social relations.

The only discourse able to impose a check on neoliberal governments was nationalism with a Catholic hue. The result is that Hungary, Poland and Slovakia today gravitate to various degrees towards fascism, or ‘Christian Nationalism’ as Viktor Orbán puts it.

This should give us pause. After 1989, all four countries in Kundera’s Central Europe entered a new phase of their histories under the auspices of democracy, pluralism and human rights. Since then, however, under nationalist governments, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia have slipped into a condition that is semi-democratic at best (with the Czech Republic showing signs of joining them). There is also particularly strong support in all four countries for European groupings that call for the defence ‘real European values’.

Such are the consequences of an uncritically accepted theory of Central European ‘exceptionality’.

Kundera cannot be held responsible for the nationalist backlash, of course. Nonetheless, his essay facilitates the repression of basic truths about our region. For example, the fact that antisemitism has historically served as a social bond; that post-war communism introduced necessary social reforms; that even before communism, authoritarianism had often been the preferred means of government; and that absence of solidarity has frequently been a principle of social policy.

This is why ‘The kidnapped West’ today demands a critical re-reading. Recent decades have shown that the myth of Central European ‘exceptionality’ leads us to forget about our closest neighbours, to violate democracy at home, and to talk about ‘sovereignty’ in order to exempt ourselves from European law. If we are to avoid this trap, we need to deepen our understanding of the dangers involved.

Kundera concluded his essay with the dramatic claim that the real tragedy of Central Europe lay in the West’s loss of ‘its sense of cultural identity’. I do not believe this was true. Nor do I believe that, even if it were true, it would have been a tragedy. The threat that Central Europe presented and continues to present to itself is considerably more serious. One could argue that Kundera was at least right in his highly negative portrayal of Russia. But even condemnation of the indisputable criminality of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine must be tempered with a note of self-criticism.

In 1989, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary presented themselves to Europe as the sole states of Central Europe, precisely as Kundera had envisaged. But if an alliance of Central European post-communist states had been founded instead, Ukraine might have been a member of the EU today and thus better protected from Russia’s aggression. Hence my view that the greatest danger facing Central Europe stems from itself: its lack of solidarity towards the EU and its immediate neighbours, its fear of the truths lodged in its own history, and its indifference to the inequalities that typify its societies.

In addition to this are the multiple crises that afflict the world today. The responses the EU has given – such as assistance in the wake of the pandemic, support for Ukraine, the relocation of refugees, the energy transition – may be incomplete and imperfect, but they have demonstrated greater integrity, solidarity and justice than anything achieved politically by the Central European countries. The real tragedy would be if Central Europe disengaged from this process and sat on the sidelines of history. If that were to happen, the Centre would shift to the periphery.

An earlier version of this article appeared in CzasKultury.pl 21 (2023).

M. Kundera, ‘The Kidnapped West or the Tragedy of Central Europe’ (‘Zachód porwany albo tragedia Europy Środkowej’). Trans. Marek Bieńczyk, WAB, Warszawa, 2023. The volume contains three additional articles: Jacques Rupnik, ‘Preface’ (‘Słowo wstępne’); M. Kundera, ‘The Literature of Small Nations: Speech delivered at the 1967 Czech Writers’ Congress’ (‘Literatura i małe narody. Przemówienie na Zjeździe Pisarzy Czechosłowackich 1967’); Pierre Nora, ‘Introduction’ (‘Słowo wstępne’).

Zeszyty Literackie, 5/1984.

Francis Fukuyama: The End of History? In: The National Interest, Summer 1989, 3–18.

Milan Kundera, ‘The Tragedy of Central Europe’, New York Review of Books, Volume 31, Number 7, April 26, 1984.

The phrase ‘younger sister’ is not used by Kundera but relates to Jerzy Kłoczowski’s monograph The Younger Europe: Central Eastern Europe in the Context of Medieval Christian Civilization (Młodsza Europa. Europa Środkowo-Wschodnia w kręgu cywilizacji chrześcijańskiej średniowiecza), Warszawa, 1998.

See ‘The Debate about Central Europe’ (‘Spór o Europę Środkową’) in The Kidnapped West: Essays and Polemics (Zachód porwany. Eseje i polemiki), Wrocław, 1984.

See A. Zagajewski, ‘A High Wall’ (‘Wysoki mur’) in Solidarity and Loneliness (Solidarność i samotność), Kraków, 1986. Arguments presented by János Kis, François Bondy and Georges Nivata we published in Zeszyty Literackie, No.7, 1984.

Czesław Miłosz, ‘Concerning our Europe’ (‘O naszej Europie’), Kultura, Paris, No. 4, 1986.

See L. Szaruga, ‘In Great Anticipation’ (‘Wielkie oczekiwanie’), Kultura, Paris, No. 5, 1986; G. Konrád, ‘A Central European Dream…’ (‘Sen o Europie Środkowej…’), Polityka, No. 46, 1988; D. Kisz, ‘Variations on Central European Themes’ (‘Wariacje na tematy środkowoeuropejskie’), Res Publica, No. 1, 1989.

See Thoughts about our Europe (Myśli o naszej Europie), Wrocław, 1988, including J. Holzer, ‘Central Europe: its past, present and future’ (‘Europa Środkowa: przeszłość – teraźniejszość – przyszłość’); K. Dziewanowski, ‘A redundant Europe’ (‘Europa nadliczbowa’); J.J. Lipski, ‘Does Poland lie within Europe?’ (‘Czy Polska leży w Europie’); J. Maziarski, ‘The Germans and us’ (‘My i Niemcy’); W. Szukalski [pseudonym for J. Maziarski], ‘Two Central Europes’ (‘Dwie Europy Środkowe’).

First Polish edition: I. Bibó, ‘The Misery of Small European States’ (‘Nędza małych państw wschodnioeuropejskich’), excerpt published in Krasnogruda, No. 2/3, 1994. For the work in its entirety including sources see I. Bibó, Essays on Politics (Eseje polityczne), trans. J. Snopek, Kraków, 2012.

Ibid. p. 57. Translation from the Polish – IM.

In 1965, a film entitled The Shop on Main Street, made by Jan Kadar and Elmar Klos, was widely shown in cinemas in Czechoslovakia. It told of the way Jewish estates were robbed in Slovakia during World War II. Although raids took place under German supervision, the Slovak community regularly participated. Kundera must have known the film, especially as it won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film in 1966.

The term coined by the Polish American historian Jan Chodakiewicz and taken up by the far-right in Poland. Chodakiewicz argued that Polish massacres of the Jews during and after the war was a justified reaction to Jewish-Communist violence. See: Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, After the Holocaust. Polish-Jewish Conflict in the Wake of World War II, Boulder 2003; idem, Massacre in Jedwabne, July 10, 1941. Before, During, and After, Boulder 2005.

In Brussels, Poland negotiated non-returnable EU grants to the value of 106.9 billion Polish zloty, and over 51.6 billion zloty in preferential loans. A total of 158.5 billion zloty. The country was due to receive the money before the end of 2023, and to use it before 2026. The funds were unblocked in February 2024.

Published 16 February 2026

Original in Polish

Translated by

Irena Maryniak

First published by CzasKultury.pl 21 (2023) (Polish version); Osteuropa 8–9/2025 (German version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Czas Kultury © Przemysław Czapliński / Czas Kultury / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Horizons of the Turkish novel; dissident disappointments; communists real and false; the feminine street.

Russian art museums and galleries, navigating Putin’s censorship, either conform or risk closure. Dissenting cultural workers are sacked, artists arrested. Pro-war propaganda is both sardonically replacing exhibitions once celebrating Soviet Ukraine in Russia and eradicating Ukrainian culture in the occupied territories.