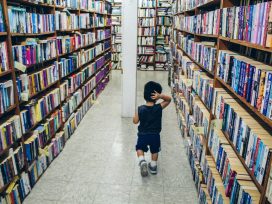

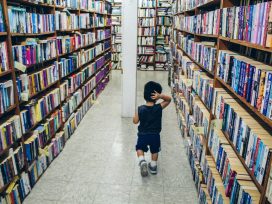

While book publishing is an ailing industry, children’s books are booming. But political attacks and censorship are also threatening this thriving sector.

Ord&Bild revisits the Fogelstad Citizen School for Women and its role in the Swedish women’s movement. With articles on prominent alumni, including working-class feminist writer Moa Martinson; modernist artist and sculptor Siri Derkert; and pedagogue and civil rights campaigner Karin Stenberg.

When women gained the right to vote in Sweden in 1919, a group of intellectuals – including Ada Nilsson (doctor), Honorine Hermelin (pedagogue and teacher) and Elin Wägner (author) – organised a course for women in political participation at a manor house outside Stockholm. The course evolved into an education centre: the Fogelstad Citizen School for Women.

With its mission to educate students as autonomous members of society, from 1925 to 1954 Fogelstad played a central role in the Swedish women’s movement. In Ord&Bild, historian Lena Eskilsson outlines how Fogelstad transformed the lives of generations of Swedish women, who learned there ‘the connections between the labour of one’s hand, mind and heart, between the domestic and the societal, between the individual and the collective’.

In order to ensure educational freedom, Fogelstad’s board of directors made a point never to seek public funding, and instead collected private donations to provide scholarships for students in need. Classes ranged from political theory, philosophy, psychology and history to literature, rhetoric, sports and music. Role-playing political processes at different levels of society also played a central pedagogic role.

Just as important as the classes were the social activities: meals, coffee breaks, parties, excursions and birthday celebrations. On some evenings, a student was chosen to sit in a designated chair and tell their peers something about themselves, their work, or their hometown.

Ord&Bild 1/2025

Eskilsson describes the school choir as a symbol of Fogelstad’s fundamental values: individual voices that came together in camaraderie. The school afforded women a place to exchange ideas, nurture friendships and build confidence. As one student put it: ‘a star of hope is brought so close to Earth that even the most stubborn pessimist can reach it.’

Ebba Witt-Brattström explores the Fogelstad School’s deep impact on Moa Martinson (1890–1964), one of the greatest Swedish writers of the twentieth century. Born in 1890 to an unwed seamstress, Martinson wrote groundbreaking prose from a feminist working-class perspective. Her acuity was already well-known in the leftist press when she first arrived at Fogelstad. After losing her husband to suicide and two of her youngest sons in a drowning accident, the school board became her close friends and support network.

Fogelstad’s co-founder Elin Wägner, who edited of its paper Tidevarvet, realised that Martinson’s radical voice was exactly what the school needed. For the first time, its bourgeois pupils could read about ‘the proletariat of the proletariat; wives of unemployed workers, the pariah of pariahs.’ Martinson narrated the poverty and brutal misogyny of the working class with humour, using the money she made from the articles to buy her own cottage (the board also funded a course in typewriting).

Together with other scholarship students, Martinson described a rewarding exchange across social classes: ‘There were large gaps in my education, literary and academic. But there were gaps in the educated women’s minds too, when it came to society and anonymous people, so it evened out.’ The students, ‘buttoned-up, shy ladies’ soon became ‘comrades’ to Martinson. Many of the Fogelstad women later appeared in her most beloved novels.

Annika Öhrner portrays artist Siri Derkert (1888–1973), perhaps the most prominent figure to come out of the Fogelstad School. A quintessential Swedish modernist, Derkert created some of the most celebrated public art works in Stockholm and was the star of the Nordic Pavilion in the 1962 Venice Biennale. Derkert first came to Fogelstad in 1943 and returned every year until it closed in 1954, lecturing in art history and teaching drawing.

The most important drawings of her career, Öhrner writes, explore the performative aspect of what she saw at Fogelstad, the moments at which women fill up a room. Derkert’s notes from the time read: ‘song and laughter – tempers and silence – the choir: songs by Jonas Love Almqvist – the most tender of songs. The lecture hall made into an instrument by sun patches, yellow squares etched onto the floor – making patterns on the ceiling, glistening sun specks on noses – hands, bodies.’

Oil paintings, drawings and collages from Fogelstad laid the foundation for her biggest artwork, the 145 metre-long mural in Östermalmstorg metro station in Stockholm. Darkert’s black abstract drawings against raw concrete were diametrically opposed to the aesthetics of the time. Women’s emancipation and peace are overarching themes in the complex composition, combining traces of music, singing women, dancing children, and snippets of lyrics from the Internationale. Combining everyday life, childrearing, love and parenthood with a peace message, Fogelstad is at the centre of the work.

Another contemporary of Fogelstad was the Sámi author and teacher Karin Stenberg (1884–1969), a central political figure in Sweden in the early twentieth century who led the struggle for Sámi rights. In a ‘letter’ to Stenberg, Susanne Ewerlöf reflects on communicating with our predecessors and speculates on the role of art in regaining what has been lost by colonisation and erasure.

‘Hello again Karin!’ she writes, ‘I feel an almost desperate need to communicate with my distant relatives after reflecting on Forest Sámi history and places where people once spoke Ume Sámi. The situation is one of violent memory loss, and it is from these broken links to the past that my despair and engagement have sprung.’

Ewerlöf recounts Stenberg’s life and contributions to the movement, most importantly her political pamphlet of 1920 entitled ‘This Is Our Wish: An Appeal to the Swedish Nation from the Sámi People.’ The pamphlet criticised colonial narratives of the Sámi as ‘ethnographic objects’ and how they enabled state violence through policies of forced assimilation policies and experiments in racial biology. ‘We, the Sámi, want to live as Sámi in the land of our fathers’, the pamphlet reads. ‘We want, like our fathers wanted, to live our natural lives in peace, looking forward and upward.’

Ewerlöf tells Stenberg how treasured her legacy has been and how the pamphlet was reissued one hundred years after its original publication. Ewerlöf grieves that Stenberg’s wishes have not been granted, and instead looks back at a century of racist oppression and destruction of Sámi lands. But Ewerlöf finds hope in the role of art: ‘a speculative form of thinking where I imagine someone like you to hear my questions, and maybe even respond’.

Review by Helga Edström

Published 3 June 2025

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

Contributed by Ord&Bild © Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

While book publishing is an ailing industry, children’s books are booming. But political attacks and censorship are also threatening this thriving sector.

Being diagnosed with ADHD can be a relief for those who have struggled long and hard to adopt constraining social norms. For neurodivergent women, masking can lead to poor mental health, substance abuse and hyper-sexuality. Vox Feminae takes a first-hand dive into positive coping mechanisms for the inattentive and/or hyperactive.