France risks becoming ungovernable. While Macron’s autocratic style is much to blame for the current impasse, the fundamental problem lies in the development of the parties and party elites.

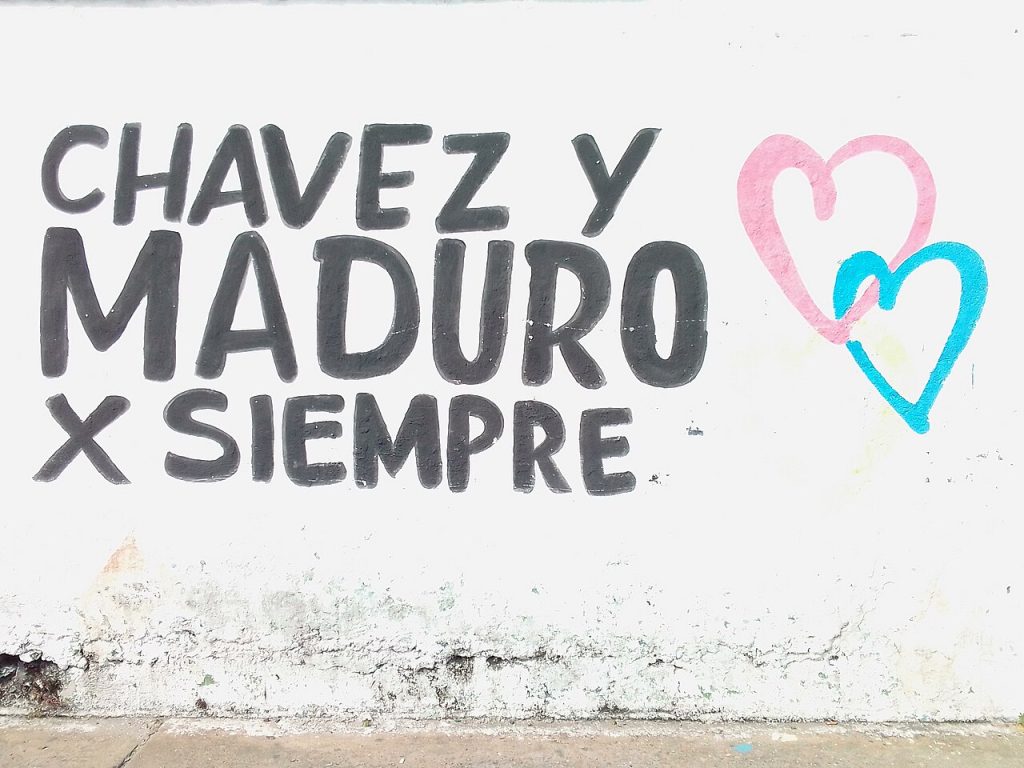

Despite a semblance of calm, Maduro’s removal has unsettled the Venezuelan regime. Will Chavismo’s tried and tested combination of coercion and expectation management continue to delay the long-awaited rupture?

In One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel García Márquez famously tells the story of the imaginary town of Macondo and its gradual exposure to the modern world. Each new development is met by Macondo’s inhabitants with a mix of fascination and bewilderment. Astonishment soon turns to doubt; revelation gives way to disenchantment. Not because the innovations are unreal, but because their accumulation produces neither learning nor lasting transformation.

Something similar is happening in Venezuela today. Each announcement of change opens a window of expectation that rarely translates into any substantial alteration of reality. Like Macondo before each innovation, Venezuela exists in a permanent state of astonishment and disenchantment. The promise of change replaces change itself, eventually emptying it of meaning.

This condition is not the result of a cultural curse or national incapacity for political modernity. Rather, it is the product of a specific way of managing time, expectation and frustration. In Venezuela, innovation long ago ceased to be a means of transforming reality. It became a mechanism for suspending it. Each new process, each round of talks, each reconfiguration of power reorganizes collective emotions. But it does not reorganize the fundamental relationships that sustain the system. The outcome is postponed without ever being resolved. The transition is announced without being permitted.

This dynamic is often interpreted as improvisation, weakness or simply political ineptitude. Yet its persistence suggests that the oscillation between hope and disenchantment is not an accident but a technique. It keeps society in motion without allowing it to advance. It produces the illusion of change without bearing the cost of real change. In doing so, it reduces immediate political pressure and displaces the conflict onto the realm of waiting.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Over time, this logic has a corrosive effect. The repetition of promises without consequences erodes not only the credibility of political actors but also the collective capacity to distinguish between progress and pretence. When everything seems provisional, nothing consolidates. Citizens learn to temper their enthusiasm, to wait without fully believing, to distrust even good news. Disenchantment no longer arrives as rupture but as anticipated confirmation. It becomes a habit.

In this context, the opposition fails not only due to strategic errors or internal divisions, but also because it operates within a temporal framework it does not control. Each attempt at mobilization is subordinated to someone else’s calendar. Each expectation generated is absorbed by a new postponement. Politics ceases to be the art of producing decisions. It becomes the management of collective anxiety.

The result is not total apathy but a form of intermittent participation: brief peaks of enthusiasm followed by long periods of retreat.

On the few occasions when the opposition has managed to influence how politics operates in Venezuela, it has come close to producing the long-awaited rupture. Chavismo’s centralized structure – which shields it from coups – paradoxically makes it vulnerable when coordinating rapid responses to unexpected events. The regime has demonstrated a remarkable capacity to impose existential dilemmas on its adversaries by forcing them to act within frameworks they do not control. However, its own cohesion tends to fracture when facing tensions of a similar nature.

This helps explain the difficulties Delcy Rodríguez has encountered in consolidating her position following Maduro’s departure. She inherited a control structure in which she and her brother occupy key positions. Yet the apparent calm of Chavismo conceals an intense inner life. Intrigue, settling of scores and persistent rumours lie beneath the surface. The sabre-rattling has grown increasingly difficult to contain.

The international community has not been immune to this dynamic. It too has oscillated between moments of activation and phases of exhaustion, between declarations of urgency and diplomatic routines that normalize the exceptional. Each new ‘decisive moment’ promises to differ from the previous one, but ends up integrated into an already familiar sequence. Expectation is renewed, the outcome postponed, and the cycle begins again. Attention becomes a scarce resource. Stagnation becomes an acceptable form of stability.

On one hand, countries of the Americas proclaim ever more rights for their citizens – many of which they are unwilling to guarantee, or whose cost they seek to transfer to the private sector, civil society or multilateral organizations. On the other hand, the history of interventions and repression in the region remains a latent fear. Within the framework of international relations, sovereignty remains the central axis of interaction. States guard it jealously. Each condemnation of the regimes in Cuba, Nicaragua or Venezuela is typically accompanied by familiar appeals to respect for sovereignty and self-determination.

This is not a genuine concern that citizens define their own future – that would mean the end of dictatorships. Rather, it is a mechanism through which states reserve the right to intervene selectively, to repress or perpetuate themselves in power. With few exceptions, governments protect their own interests first, and only afterward those of the region’s citizens.

The social cost of this oscillation is profound. Mass emigration cannot be understood solely as a response to the economic or humanitarian crisis. It is also a silent retreat from waiting. Millions of Venezuelans did not abandon the country only because life became unviable. They left because time ceased to offer a horizon. For many, emigrating was the only way to break the cycle – to escape a promise that no longer promised anything.

Venezuelan authoritarianism combines two pillars of control. On one hand, there is direct coercion: repression, political prisoners and selective violence. This keeps any immediate challenge in check. On the other, there is the management of expectation and ambiguity, which prolongs uncertainty and dispenses hope in calculated doses.

The regime does not eliminate the illusion of change. It rations it. It opens escape routes that rarely lead to real transformation. Physical coercion and the manipulation of political time work hand in hand. If the opposition crosses certain boundaries and poses a genuine challenge to Chavismo’s hegemony, the first pillar always remains an option.

Venezuela’s problem, then, is not the absence of change but its constant simulation. Politics is filled with signs of innovation that produce no innovation whatsoever. Like in Macondo, the accumulation of events does not generate memory or learning but rather confusion. And within that confusion, immobility becomes stable – not because nothing happens, but because nothing happens with lasting consequences.

Breaking this cycle would require more than a new promise or a new milestone. It would mean restoring the relationship between expectation and transformation, between announcement and outcome, between political time and social experience. Until that happens, Venezuela will remain trapped between the illusion of change and the persistence of waiting.

Published 26 January 2026

Original in Spanish

Translated by

Lola Rodríguez

First published by Letras Libres (Spanish version); Eurozine (English version)

Contributed by Letras Libres © Letras Libres / Pedro Garmendia / Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

France risks becoming ungovernable. While Macron’s autocratic style is much to blame for the current impasse, the fundamental problem lies in the development of the parties and party elites.

The Courts have acquiesced, the populace is compliant and the Democratic Party is splintered. Without any way to make their opposition felt, Trump’s opponents’ only hope is that the economy will cause MAGA voters to rethink.