We have all seen the blonde-fringed Tintin wriggle his way out of one sticky situation after another. But early 2010 saw the Belgian national hero’s past catch up with him; a past most of us had forgotten he had. Congolese Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo believes the comic book Tintin in the Congo is racist and should be banned, and has taken legal action against the series’ copyright-holder Moulinsart and its publisher Casterman.

It was during his second adventure, published in 1931, that Tintin travelled to the Congo, a Belgian colony at the time. There he was mixed up in a gangster showdown when some of Al Capone’s partners tried to take over the country’s diamond production. The early Tintin books are crudely drawn and feature a coarse style of humour, such as when Tintin escapes an angry rhino by blowing it up with dynamite. Even more notorious is the sequence where he visits a school to teach geography. “Dear friends,” he says to the Congolese children, “today I’m going to tell you about our country: Belgium.” This is the colonial master talking. In another sequence, he repairs a broken-down train for the helpless locals. In the new colour version of Tintin in the Congo, published in 1946, the geography lesson has been replaced by mathematics and the Congolese speak more comprehensible French, but the tone is still condescending. The population is presented as naive and lazy; a land of childlike beings.

A not altogether unnatural immediate reaction to Tintin’s paternalistic manner is that he ought to take a trip over here [Norway] and sort out our rail system – we can chuckle about that kind of thing. However, Tintin’s trouble in his home country is no laughing matter. “J’accuse,” proclaims [the plaintiff] Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo indignantly, and denounces the album as “offensive and demeaning to all Congolese”.

The court case was big comic-strip news during the first half of the year and also made it into the Nordic newspapers. Politiken, Aftenposten and VG have, one after the other, featured big headlines proclaiming that a verdict will soon be reached on whether Tintin is racist or not. But the verdict has been postponed every time. What is so controversial about the case is that Mondondo is right but ought nonetheless not to be proven right.

More on that later. To say something about what we can learn from Tintin’s 20-year-old prejudices, let’s go from the courts in Brussels to a rather more direct verdict handed down by a group of Norwegian school children.

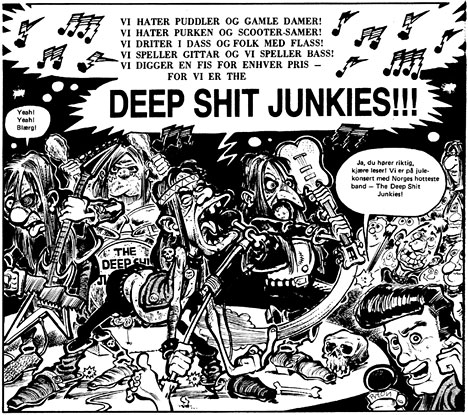

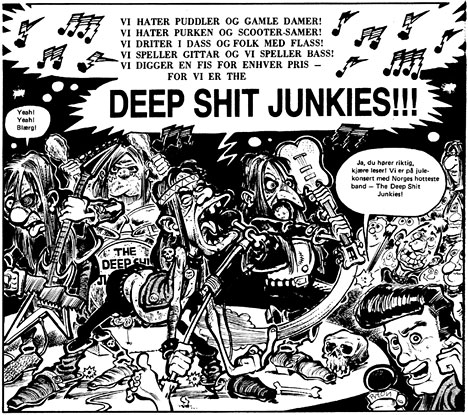

I had a Tintin in the Congo-experience myself when I gave a comics course at the Sami school in Tana [a municipality in Finnmark in Norway]. As part of The Cultural Rucksack (a national arts and culture programme for schools), I visited schools all over the Finnmark area in the same way I had previously given courses at many schools in South-Eastern Norway. One of the pictures I used to demonstrate the use of speech bubbles comes from Frode Øverli’s nineties series Deep Shit Junkies, from the comic Pyton. It was an amusing drawing featuring obvious typographical effects, where a caricatured singer howls a song displayed in bold text and capital letters. But it was the content of the speech bubble that got the Tana pupils’ attention.

The moment the image came up on the screen, the hum of small-talk started up among the pupils who were usually rather groggy in the mornings. At first I didn’t understand what they were mumbling about but then I had a second look at the drawing – or more accurately, the text. I had read and commented on the speech bubble before so I knew it by heart down to the last exclamation mark, but it was only now that I fully registered what it actually said. The singer shouts: “We hate poodles and old ladies! We hate the filth and scooter Samis! […] We play guitar and we play bass and we’ll fart any place – ‘coz we are The Deep Shit Junkies!!!” It wasn’t the contingency rhymes and dithering metrical feet that provoked the children in Tana; it was the phrase “scooter Samis”. “Why does he hate Samis?” asked one of the pupils, the others nodding in supportive bewilderment. No doubt for Frode Øverli it had much more to do with getting the last line to rhyme than with spreading a hatred of Samis, but a comic can be read on many levels. It was easy to understand the pupils’ reaction.

The moment the image came up on the screen, the hum of small-talk started up among the pupils who were usually rather groggy in the mornings. At first I didn’t understand what they were mumbling about but then I had a second look at the drawing – or more accurately, the text. I had read and commented on the speech bubble before so I knew it by heart down to the last exclamation mark, but it was only now that I fully registered what it actually said. The singer shouts: “We hate poodles and old ladies! We hate the filth and scooter Samis! […] We play guitar and we play bass and we’ll fart any place – ‘coz we are The Deep Shit Junkies!!!” It wasn’t the contingency rhymes and dithering metrical feet that provoked the children in Tana; it was the phrase “scooter Samis”. “Why does he hate Samis?” asked one of the pupils, the others nodding in supportive bewilderment. No doubt for Frode Øverli it had much more to do with getting the last line to rhyme than with spreading a hatred of Samis, but a comic can be read on many levels. It was easy to understand the pupils’ reaction.

It also got me thinking about how many Norwegian comics to a large extent rely on reactionary prejudice to score easy points in the humour stakes. This was probably not the issue the now wide-awake secondary school children were most interested in, so instead I reassured them that the singer didn’t mean it like that – and clicked on to another example of a comic, one without text. For the remainder of the school visits I discarded that particular slide. Forgive me Frode Øverli, but a certain level of censorship is required.

Humorous comics are a dominant genre on the Norwegian comics market. Many, if not most, of today’s popular series can be traced back to Pyton. The magazine first appeared in 1986 and kept going for over ten years with licensed editions in both Finland and Sweden. Pyton is perhaps most famous for giving fat-ass humour a face, but was also of huge significance to the development of Norwegian commercial comics. Pondus-creator Frode Øverli, Donald-artist Arild Midthun (alias Arnold Milten) and Radio Gaga‘s Øyvind Sagåsen, to name but a few, learned their craft from Pyton. The magazine’s coarse humour was a trend setter. The main character, Dølle Døck, was not just Donald’s sleazy cousin; he was also the Neanderthal version of Pondus. Dølle’s world consisted of beer, football, women and homophobia, only it had a more desperate and vulgar quality than in more recent series.

Pyton‘s role model was the American MAD, created by Harvey Kurtzman in 1952. His satire bred a critical media awareness that not only influenced later underground comics but also TV-programmes like Saturday Night Live and the Comedy Central channel.

While MAD expressed the zeitgeist, Pyton lived in its own world. Pyton can be, but really shouldn’t be, read as extreme postmodernism. In actual fact, Pyton distorted MAD‘s satirical revolution into nonsense. The magazine was created when the makers of Norwegian MAD decided to draw and write with a rawer kind of humour. Pyton‘s loutishness may at the time have been regarded as daring but in retrospect it is much less challenging than the satire behind MAD. Today, Pyton comes across as neither anti-authoritarian nor avant-garde in the larger societal context. On the contrary, it has laid the foundations for self-affirming and prejudiced humour.

This stupidity-spawning humour is most clearly expressed in the national scourge that is Pondus. Since Frode Øverli began the series in 1995, it has become the most popular Norwegian comic of all time with several hundred thousand reading it in newspapers, magazines, books and online. Pondus is chauvinist, and virtually all its humour is prejudice-based. The comic is especially discriminatory against women and homosexuals. It is the loud-mouthed attitudes in the man-to-man dialogues throughout the series that carry it.

The value system in Pondus is extremely simple. The comic celebrates football, fishing, beer, whisky, heavy foods, poker, rock and TV. It opposes hairdressers, pop music, clothing salespersons, poetry, leather-clad gay people, wine and gourmet food. The macho Pondus hauls out the biggest fish from the lake, plays dirty on the football field and is incapable of washing clothes. The enemies are men who aren’t really men: ridiculous, henpecked men represented by his neighbour Harold, and comical or threatening gay people. Gay “clowns” are, for example, the kind that trudge about the streets in leather and fishnet stockings with paperclips through their heads. “That’s how people who don’t play football end up like!” says Pondus to his son. Gay “monsters” are muscly, over-sexed types. When his mate Jokke ends up in jail after attacking his own mother, he has to share a cell with two large men. One of them is dressed in a string vest, has a wooden leg and a metal hook, and “Per” tattooed in a heart on one bicep.

The point of origin for the comical effect in a number of the sequences is the male fear of touching other men. When Pondus oversleeps, his wife and son resort to skin-to-skin contact with an inflatable muscle-man and music by the Village People. It is especially in the relationship between Pondus and Jokke that this fear of touching is apparent. Jokke is jovial and clingy while Pondus is reserved and worried about what people might think.

Is Øverli ridiculing the personalities he caricatures or is he attacking the prejudices? The answer is mostly the former but the comic should be read more like a vulgar joke than an intentional denunciation. Sequences featuring, for example, gay people, artists and car mechanics are based on an instinctive recognition from within the reader’s own prejudices. The humour certainly does not problematize such attitudes but rather confirms, in its graphic way, that there must be a seed of truth here.

While satire is, by its very nature, anti-authoritarian, Norwegian comic caricature aims down as well as up the social ladder. There are a few exceptions. Lars Lauvik’s EON has homed in on members of the elite society. Both Karine Haaland and Christopher Nielsen turn the usual role models upside down; Nielsen transforms society’s outsiders into main characters in unpredictable ways. Most, however, follow in the footsteps of Pyton and Pondus. We see this in more recent series on the website http://nettserier.no/, and in more established series like Øyvind Sagåsen’s Radio Gaga and Torbjørn Lien’s Kollektivet. Among the main characters in Lien’s comic are a young Muslim and a lesbian woman. Now and again, the comic can surprise you with broad-mindedness, but for the most part it stigmatizes the masculine North-Norwegian woman and the Muslim’s fundamentalist family.

Frode Øverli knows how to use the kind of phenomena and prejudices with which most people are familiar. That is why Pondus has become a local hero. The series does nothing to challenge our irrational intolerance. On the contrary, it is stuck in past values and offers daily confirmation that different equals strange. We can but speculate about the nature of the trials against Pondus that will hit the courts in 2090.

What is it about Tintin that in 2010 has made him the subject of a court case over an eighty-year-old album? From the very beginning of the series, on 10 January 1929 in the Belgian newspaper Le Vingtième Siécle, the reporter Tintin came across as a Western globetrotter with a highly developed boy scout-spirit. Tintin is one of the most popular comics in the world and has sold almost 200 million albums. Much of the reason that Tintin has managed to captivate readers over several generations is that the comic forms the definitive western comic-book adventure. The energetic Tintin guarantees that the powers of Good and Rationality will be victorious, in an exotic world of naive savages, raining meteors and eccentric personalities like Captain Haddock, Professor Tournesol and Madame Castafiore (the comic’s only noteworthy female character).

A key theme in all the biographies about the comic’s creator Hergé is the link with the occupying Nazi forces during the Second World War. The editor of the newspaper Le Vingtième Siécle was Norbert Wallez, a Catholic fundamentalist who disliked Jews and admired Mussolini. There is little doubt that his ideological opinions influenced Hergé. Another source of inspiration may have been the fascist Rexist Movement, which, during the interwar years, campaigned to strengthen Christian morality in Belgium. In his twilight years, their leader, and later SS-officer, Léon Degrelle claimed to have been Tintin’s role model. During the war, Tintin was printed in the German-friendly newspaper Le Soir. After the liberation, Hergé was arrested several times but the charges were dropped without a verdict. While Hergé’s drawing style and narrative economy have become a role model for several generations of comic creators, the series’ often outdated ideology and attitudes have become a symbol of old colonial Europe. When Joann Sfar, in one of the biggest French series of the 2000s, The Rabbi’s Cat, addresses tolerance and confrontation between Judaism and Islam in Africa, it is precisely Tintin in the Congo that is one of the most direct, key references.

Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo is citing a Belgian anti-racism law from 1981 and there is little doubt that Tintin in the Congo is racist. From that perspective, he could win the case to have the album banned or at least equipped with a warning label identifying racist attitudes, like the one already on the English version. If Mondondo’s case is not proven it will be because the album first and foremost is a document of its time. Tintin is an illustrative expression of the colonialist view of the Congo and the average African person in the 1930s. We cannot prohibit historical facts, regardless of how uncomfortable they may make us feel, but we do have to criticize and discuss them. Mondondo reported the album in 2007, but criminal proceedings were not initiated. After three years of restraint, he has now filed civil proceedings, which have currently stalled at the hearing stage. So it would seem that the Belgian legal system’s handling of the case is just as scandalous as Tintin in the Congo.

The moment the image came up on the screen, the hum of small-talk started up among the pupils who were usually rather groggy in the mornings. At first I didn’t understand what they were mumbling about but then I had a second look at the drawing – or more accurately, the text. I had read and commented on the speech bubble before so I knew it by heart down to the last exclamation mark, but it was only now that I fully registered what it actually said. The singer shouts: “We hate poodles and old ladies! We hate the filth and scooter Samis! […] We play guitar and we play bass and we’ll fart any place – ‘coz we are The Deep Shit Junkies!!!” It wasn’t the contingency rhymes and dithering metrical feet that provoked the children in Tana; it was the phrase “scooter Samis”.

The moment the image came up on the screen, the hum of small-talk started up among the pupils who were usually rather groggy in the mornings. At first I didn’t understand what they were mumbling about but then I had a second look at the drawing – or more accurately, the text. I had read and commented on the speech bubble before so I knew it by heart down to the last exclamation mark, but it was only now that I fully registered what it actually said. The singer shouts: “We hate poodles and old ladies! We hate the filth and scooter Samis! […] We play guitar and we play bass and we’ll fart any place – ‘coz we are The Deep Shit Junkies!!!” It wasn’t the contingency rhymes and dithering metrical feet that provoked the children in Tana; it was the phrase “scooter Samis”.