I wanna look like what I am but don’t know what someone like me looks like. I mean, when people look at me, I want them to think “there’s one of those people that has their own interpretation of happiness”. That’s what I am.

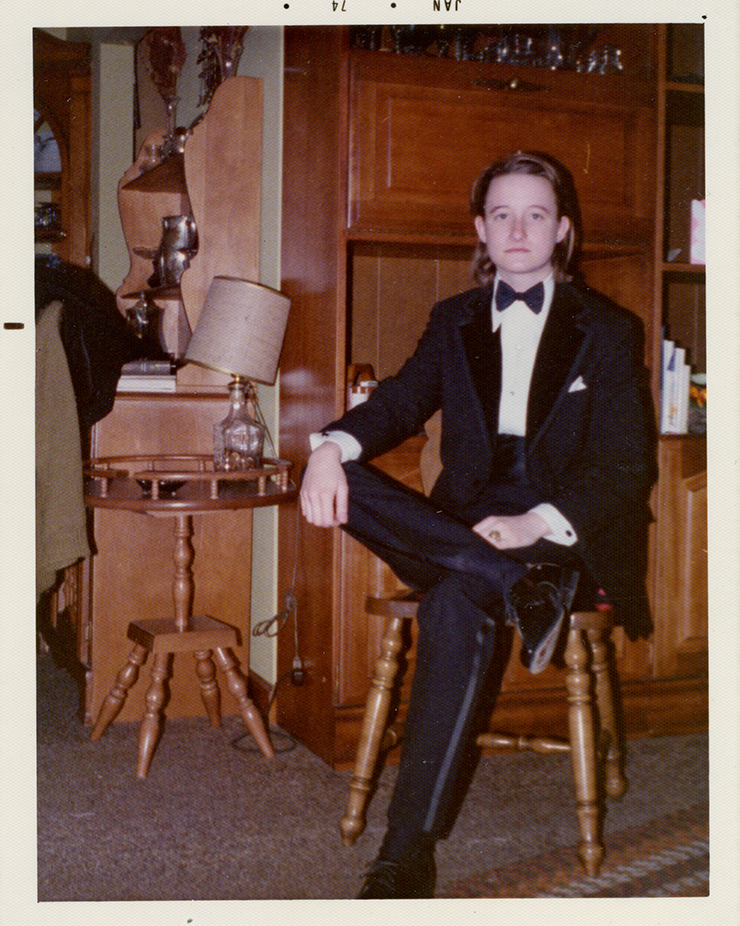

Lou Sullivan was born in Milwaukee, USA, in 1951 and passed away from AIDS-related complications in 1991. His written legacy includes the biography of transgender man Jack Bee Garland (1869-1936), several transition guides and the diaries he kept from the 1960s. His journaling, which he intended as an aide-mémoire for when he grew older, was posthumously published. As one of the first openly gay trans men, Sullivan is also remembered for the support groups he organized, his discussions with experts and his self-advocacy. In another world, he would be 74 this year. Perhaps he would be found hanging out with other older gay guys on YouTube watching Gottmik’s run of Rupaul’s Drag Race. In this life, though, he is gone, and all we have of him is his writing.

We Both Laughed in Pleasure is Ellis Martin and Zach Ozma’s 2019 version of Sullivan’s diaries. Their approach involved removing individual entry dates and editing down a good proportion of the diary entries. The book instead is divided into the years Sullivan spent living in certain places, and focuses on his sexual orientation and gender identity. Some readers might find such an editorial choice concerning – whether pornography or invasive questions, we live in a society obsessed with genitalia when discussing transgender issues. But I believe Martin and Ozma’s focus is not without merit.

The AIDS Crisis

Sullivan’s life should be remembered within its historical context. The first cases of AIDS, which were initially described as instances of unusual pneumonia, date back to July 1981, six months after Ronald Reagan became US president. His response to the epidemic – if such an intentional lack of action can even be called a response – carries much of the blame for the disease’s expansive death toll. Today, HIV+ individuals can live long and healthy lives. Back then, millions died in a matter of decades. To say that the modern LGBTQIA+ community was shaped by this event would be an understatement.

Sullivan approached his diagnosis much like any other event in his life – he was vulnerable, open, defiant and funny about it. ‘They told me at the gender clinic that I could not live as a gay man, but it looks like I will die as one,’ he wrote. Sullivan’s reflection towards the end of his life echoed his younger self’s attitude towards homophobic heckling – very much ‘thanks for the gender affirmation, but good god’.

His AIDS diagnosis was far from the first hurdle in his life. The diaries follow him through several deaths in the family, which informed his final moments:

I find it too hard to believe that someone could love me enough to go through that with me…that my dying could have such a significance to someone else. But I have to recall my own feelings when dad and Kathleen were so disabled and needed our love and whatever help we could give. I’d’ve done anything to ease their transition, and so I must believe that those who love me (Maryellen, Kathy, mom) will be there for me, too.

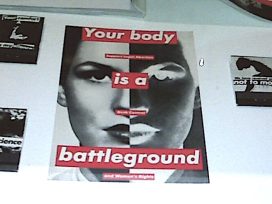

What he describes is a close-knit, well-organized community. We see how important Sullivan was to his loved ones: hordes of people volunteered to help care for him, and those already mourning him often turned to him for comfort. We also see how important each individual member was to the LGBTQIA+ community: those running food programmes to feed the sick; a growing section of the annual Pride parade dedicated to disability. Love and solidarity survived both of Reagan’s presidential terms.

Joy, despite it all

That same spirit of defiance and closeness is evident when Sullivan describes sex. We follow him to group masturbation clubs (a form of safe sex in a time of medical uncertainty), we learn of different understandings of physical affection, and we see him celebrate the body – the pleasure his own and those of others could give him, even while dying from a virus. He became aware that he belonged amongst gay men early on in his life, and in his twenties wrote: ‘Said the only crowd I feel relaxed in is the gays x I can’t be 40 yrs old x still hanging around them x he asked why not? He was so logical, I realized I was building it all up in my mind. Why not indeed!’ Though Sullivan barely made it into his forties, he did make it surrounded by fellow gay men. His last diary entry describes his upcoming plans – his favourite author was about to hold a speech, a friend had promised to take Sullivan there – but he passed away a couple of days later, and the community had to finish his work.

A big focus of this edition is on Sullivan’s medical transition. The diaries describe effects of taking testosterone, a mastectomy (also known as top surgery) and finally an early version of a phalloplasty Sullivan only completed a few years before his passing. Each step brought Sullivan closer to complete happiness: he describes his flat chest, his muscles, his hairy legs and penis, and finally both testicles (the left one caused him some trouble) with palpable gender euphoria, the lesser-known twin of gender dysphoria. Sullivan loved being a man, loved being gay and loved every part of himself that society wanted him to be ashamed of. ‘Sudden thought: If the psychiatric profession has decided that being homosexual is no longer a sign of mental disorder, then how come wanting to be homosexual is so mental??’ was his response to the confusion health providers expressed over his never-before-seen identity. He refused to lie about his sexual orientation to ease his transition process. He refused to let anyone convince him he was a woman suffering from misogyny and even reported less animosity towards femininity once womanhood was no longer being forced upon him. When he noticed a lack of FTM support groups, he started his own.

A big focus of this edition is on Sullivan’s medical transition. The diaries describe effects of taking testosterone, a mastectomy (also known as top surgery) and finally an early version of a phalloplasty Sullivan only completed a few years before his passing. Each step brought Sullivan closer to complete happiness: he describes his flat chest, his muscles, his hairy legs and penis, and finally both testicles (the left one caused him some trouble) with palpable gender euphoria, the lesser-known twin of gender dysphoria. Sullivan loved being a man, loved being gay and loved every part of himself that society wanted him to be ashamed of. ‘Sudden thought: If the psychiatric profession has decided that being homosexual is no longer a sign of mental disorder, then how come wanting to be homosexual is so mental??’ was his response to the confusion health providers expressed over his never-before-seen identity. He refused to lie about his sexual orientation to ease his transition process. He refused to let anyone convince him he was a woman suffering from misogyny and even reported less animosity towards femininity once womanhood was no longer being forced upon him. When he noticed a lack of FTM support groups, he started his own.

Medical gatekeepers, new and old

As I read about his medical transition, I was struck by how little appears to have changed. Sullivan navigated the process with the help of Steve Dain, a fellow trans man who instructed him on who to reach out to, what to expect and how to self-advocate. Medical transition, when available, follows two main models. The first, based on informed consent, allows anyone to reach out to a health provider, express an interest in medical transition, and be informed of potential risks and expected effects. The person can then decide for themselves whether they want to start hormones, undergo surgical procedures, etc. The transgender person is therefore treated as the expert on their own identity, and the health provider is there to aid them and educate them about available options. The second model, visible in Sullivan’s diaries, demands that transgender individuals convince enough cisgender people that they indeed are transgender – a process that can sometimes take years. It relies on an unofficial network of trans people to guide each other towards providers familiar with transgender people, keep track of who they need to speak to and in which order (the general practitioners who write our referrals often know very little about the process). We even teach each other the acceptable personal stories to tell the psychologist, lest the expert be confused by the overly complicated fact of an individual personality.

This same story plays out on the pages of Sullivan’s diaries. Transgender people are required to become experts on medical experts, while those medical experts fail to show much expertise when it comes to us. The irony is greater because the same medical experts learn from us, but only under set conditions – I am asked to fill out survey after survey from psychologists interested in queer issues, but were I to show up on their doorstep with a referral, it would take them three to four sessions to decide if I was trustworthy. By the end of his life, Sullivan was a recognized authority on transgender issues. Had he believed the expert gatekeepers, he would have died as an unhappy and forgotten ‘woman’ in a leather jacket.

Who is the authority?

A 2024 study by social psychologist Jaime Napier reports global attitudes towards the trans community, including whether people believe in transgender identities. Participants in the study were asked to rate their agreement with the statement, ‘A person cannot really be a different gender than the one they were considered at birth’. The highest agreement with this statement was found in Russia, though the USA was not far behind – so at least we know what won’t cause the next Cold War. The most promising results were reported in Spain, where the least number of participants agreed with the above statement. Spain, interestingly, practices informed consent. It is hard to tell which came first, but I do not find it surprising that the country where a trans person’s authority on their own identity is recognized doesn’t struggle to accept that trans people exist.

I did not set out here to summarize Sullivan’s diaries. I invite everyone to read them for themselves, and enjoy the anecdotes of sexual sadomasochism, adolescent Beatlemania, timeless humour, and poignant reflections on life and death. Rather I am keen to defend a preoccupation with LGBTQIA+ identities. Sullivan is called upon here as a kindred spirit, as he himself stated that his life goal was to prove to society that people like him exist.

When not erased, LGBTQIA+ identities tend to be pathologized, turned into stereotypes and relentlessly demonized. Sullivan saw through this and recognized himself as a gay man, forcing the healthcare system to redefine existing categories. The way LGBTQIA+ identities are presented to the world often follows the same narrow, fatalistic formula, and Sullivan managed to combat this through stubborn self-identification. Focusing on his identity doesn’t reduce him to a label – it challenges a reductive view of the label itself.

This article was first published by Vox Feminae. Its translation from Croatian into English was commissioned as part of Come Together, a project leveraging existing wisdom from community media organization in six different countries to foster innovative approaches.