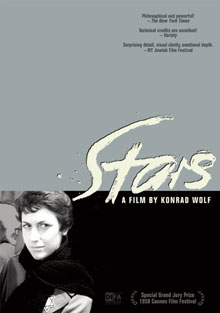

Distancing itself from earlier studies, recent scholarship on the cinematic representation of the Holocaust has demonstrated that the portrayal of anti-Jewish persecution did not remain taboo throughout the socialist era in eastern Europe. A segment of this scholarly literature has explored the gendered dimensions of the filmic rendering of Jewish victimhood and agency in eastern Europe. In a recent contribution, for instance, Anke Pinkert has investigated the changing depictions of Jewish manhood in GDR cinema with a view to “re-examin[ing] discourses of victimization and perpetration”. Focusing on the interpretation of womanhood in film, the present article aims to contribute to the growing body of literature by tracing the inception, making and reception of Zvezdi (Bulgarian title), or Sterne (German title), a Bulgarian-East German co-production directed by Konrad Wolf. The film, which was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Festival in 1959, tells the story of an impossible love between a German Unteroffizier and a Greek Jewish woman who was detained with other Jews from Bulgarian-occupied Western Thrace in a Bulgarian transit camp, pending deportation to Poland. In the movie, Jewish suffering is primarily embodied in one female character, Ruth, a school teacher.

In mainstream film history, the film has often been reduced to a DEFA (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft) movie and studied as a lens through which Konrad Wolf’s artistic career can be viewed. This interpretation of Zvezdi/Sterne (“Stars”) as a German auteur film omits that the movie was the first in a series of artistic and financial co-productions by East Germany and Bulgaria. Zvezdi/Sterne is based on a script by Bulgarian writer Anzhel Wagenstein, himself a witness of the historical events recreated in the piece. As a member of a Jewish forced labour unit in Pirin Macedonia (Bulgaria), Wagenstein was working at a railway construction site when he witnessed the Jewish transports from northern Greece on their way to Poland. In addition, as I have argued in detail elsewhere, the production of the movie was intended to strengthen bilateral relations within the “Soviet bloc”. Most important, the film is evidence of the painstaking negotiation process of creating a socialist memory of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Within the framework of this article, I shall consider the allegorical use of womanhood from a cultural-historical perspective that treats films not only as visual, textual and auditory products, but also as part of a social process of collaboration. With a view to complementing the extant literature, which is based primarily on German archival material, the article analyses documents from the Bulgarian State Archives, notably the minutes of the meetings of the Bulgarian-German artistic council, which met most often in Sofia and occasionally in Babelsberg. These sources permit a rare insight into how the Bulgarian and German partners conceived of the “Jewish catastrophe” and imagined gender roles. Particular attention will be paid here to the use of Christian symbols to represent Jewish suffering.

1. Second to the man: Being a woman in a “Roman d’apprentissage”

A classic melodrama, Zvezdi/Sterne revolves around three main characters: Walter, a painter turned into a German non-commissioned officer by the war; Kurt, his captain and friend, who is meant to typify the selfish, remorseless German fascist; and Ruth, a Greek Jewish teacher. Disillusioned as he witnesses the regression of humanity to the stage of “chimpanzees” (one of his favourite terms) under the influence of the war, Walter undergoes a progressive transformation as he develops feelings for Ruth, a Jewish detainee he met in the camp. As he falls in love, he abandons his detached and contemplative attitude and decides to act. His commitment is originally limited to saving the woman he cherishes. Once this attempt fails – his German friend, Kurt, lies about the timing of the transport, so that when Walter comes to rescue Ruth, he finds the camp empty –, however, he offers his help to the Bulgarian Partisan movement, rallying the anti-fascist struggle. At the end of the learning process/film, Walter has come to realise that no human being can remain passive in the face of injustice and violence.

In the movie, the fashioning of Walter as a reluctant would-be hero marks a striking departure from the conventional narratives of the previous years. In Bulgaria as in the GDR, mainstream anti-fascist movies, a well-established genre, had until then emphasized the virtue of the collective. They tended to reify the valour of the Partisan movement and criticized people with fledgling ideological beliefs and hesitant attitudes. However, Walter remains far removed from archetypical fascists and freedom fighters. He is the sole protagonist who experiences a character development in the course of the film. Even though the script emphasizes Ruth’s education, language skills (Ladino, Greek, German) and determination to protect her fellow inmates in the camp (including her reluctance to tell the truth about their ultimate destination), she becomes more and more resigned as the story advances. Most of her encounters with Walter occur as she is summoned up from the camp at night and engages in long walks alongside the German Unteroffizier (permission is granted by Kurt, who believes that the detainee will provide welcome entertainment to his sad friend). During the first talk, Ruth is pictured sitting very upright at the top of a hill gazing at the horizon, while Walter sits below her in a gesture of abandonment. In later scenes the camera gives greater precedence to the male character, whose gentle, yet dominant position is confirmed at the moment when he bends over Ruth to kiss her. Confronted with the ruthlessness of the times, the Jewish teacher, who had preached hope in her initial encounter with Walter, fails to act beyond the expression of a dignified refusal to be saved. For the most part, she functions as the German Unteroffizier‘s conscience, telling him, “You are all responsible for what has happened over the past years.” “I did not want it”, he protests. Ruth replies, “You did not want it, but you let it happen.”

Was Ruth’s characterisation as a mostly passive protagonist, whose main function is seemingly to extol the virtues of the potentially good German male and to help him mature, intended by the scriptwriter and the Bulgarian-German artistic council? To answer this question, one must move away from the visuals and explore the bilateral discussions held during the production phase. With the establishment of socialist regimes in Eastern Europe, a state monopoly was instituted over the production and distribution of films. Like their Soviet counterparts, Bulgarian and German socialist rulers regarded cinema as a powerful means of political education. In Bulgaria, a new public production company, D.P. Bulgarska Kinematografia, was established and placed under the authority of the Committee for Science, the Arts and Culture. In June 1950, the company underwent an organizational reform with the creation of an artistic council (hudozhestveni suveti), whose role was to define thematic plans, assess the quality of cinematic projects and determine whether films should be released or shelved. Within D.P. Bulgarska Kinematografia’s three film studios (Documentary Studio, Feature Film Studio, Studio for Popular Educational Films) smaller artistic councils were set up with representatives of the various branches of the profession, who were responsible for overseeing the production process. They soon established themselves as both collaborative institutions and instruments of (self-)censorship. Following the signing of a co-production agreement between DEFA and the feature film Studio Boyana in May 1957, a dozen meetings took place, attended by a changing list of German participants: directors Konrad Wolf, Kurt Maetzig, and Wolfgang Kohlhaase; cinematographer Werner Bergman; script editor Willy Brückner; film producer Siegfried Nürnberger; and members of DEFA’s leadership, including DEFA director Albert Wilkening.

These bilateral discussions yield useful insight into the interpretation of the heroine. In July 1958, for instance, the final version of Wagenstein’s screenplay awaited approval. On this occasion, filmmaker, scriptwriter, and actor Dako Dakovski, a member of the artistic council, explains how he understands Ruth’s role:

In the first scene, the “discussion between Ruth and Walter at night during the walk’, Ruth’s attitude towards Walter seems unprepared, not motivated […]. Perhaps in this scene one should avoid this rapid opening, this rapid intimacy between Ruth and Walter. At present everything is uncovered from the first scene and somehow the relationship of Ruth to Walter does not play any role further down the storyline in the fate and the behaviour of Walter.

Ruth’s instrumental position is further outlined when members of the council criticise the fact that the Jewish teacher Ruth is presented as the main force behind the moral rehabilitation of Walter. Communist writer Pavel Vezhinov, a member of the artistic council, makes this point clear:

The greatest weakness lies in the fact that the Bulgarian side is rendered mechanically […] in an external, declarative, and stereotyped way. […] The actual dramatic conflict lies between Walter and Ruth. Walter is a good guy with a certain level of integrity – he builds a bit of theory to present himself as a clean person and closes his eyes to the crimes committed around him. Upon his character, Ruth is the one who exerts an influence. And it is through general humanistic positions that she weighs upon him. […] It would be nice if the author could find some small ways, some marginal changes in the screenplay so that one feels that the Bulgarian revolutionary movement too influences the ethical and moral stance of Walter […]. Comrade Ginev is right when he says that one should clarify the relations between Walter and Blazhe [a young Bulgarian partisan].

Thereby Pavel Vezhinov voices two points of criticisms on the part of the Bulgarians that recur throughout the production process: Firstly, several male duos involving members of the Partisan movement ought to be brought into sharper relief; secondly, Walter’s change in behaviour should be matched with a conversion to the socialist creed. More specifically, two contentious issues dominate the discussions between the Bulgarian and German partners: How should the Germans be depicted, and how could the film offer a true rendering of the suffering of the Bulgarian people and their contribution to the anti-fascist struggle? Unlike DEFA officials who were eager to present the film in Cannes and, thereby, demonstrate the artistic might of East German socialism before the world, the leadership of the Bulgarian film monopoly was dissatisfied with the answers the film crew offered to both questions, and stated its reluctance to see the movie released in January 1959. From their standpoint, the valour of Bulgarian partisans was not emphasised enough, relations between Bulgarians and Nazis were too cordial, Walter presented too lenient a view of the Germans, and the hostility of the Bulgarian people to anti-Jewish measures did not stand out as it should have. Ultimately Zvezdi/Sterne premiered in Sofia on 23 March 1959, but it was offered only limited exposure in Bulgaria until the Cannes Film Festival in May introduced it to a larger audience.

2. Close-up beauty and the making of purity

As Daniela Berghahn has rightly noted, the use of women as a means to enhance their male partners was standard practice in early DEFA anti-fascist films: “the chief function of women in the films’ narrative economy”, she argues, “was to heighten the trope of self-sacrifice around which the antifascist genre is structured.” Until the 1960s, few DEFA stories were told from a woman’s perspective and women were largely confined to the role of the helper. Zvezdi/Sterne, however, deviates from this pattern, if only because it is the heroine who is sacrificed in the end, not the hero, as was conventionally the case in GDR (and Bulgarian) anti-fascist movies. More important, in a tradition where socialist characters were supposed to serve an allegorical function and films were to offer parables, Ruth is designed to symbolically represent Jewish suffering. Let us now examine what kind of actress and what female subjectivity the movie’s creators perceived as appropriate to represent the genocide of the Jews.

According to the agreement concluded between DEFA and Studio Boyana, the German side was to provide the actors for the three lead roles Walter, Kurt, and Ruth. At the Karlovy Vary Festival in 1957, Konrad Wolf decided on Haya Hararit, an Israeli actress born in Haifa in 1931, who was to earn fame in Ben-Hur (dir. William Wyler) opposite Charlton Heston in 1959. During a meeting in April 1958, Bulgarian director Borislav Sharaliev, a member of the artistic council, grudgingly supported the choice of Hararit. Meanwhile, he betrayed his own reading of Ruth’s character, whom he pictured as a charming young lady.

Borislav Sharaliev:

As an actress, I like Haya Hararit, but to me Ruth’s character is associated not only with moral purity, but also with external purity. I have imagined Ruth as a very beautiful, a very nice woman, not necessarily very young. Here, however, I do not get the impression of a beautiful young lady. Perhaps later, with the proper kind of light, her face will create a different expression and some defects will get covered and shaded. I would not be against a good and significantly more beautiful actress.

Konrad Wolf:

The question of beauty, in particular when it comes to a lady, is of course a question of taste. I find Haya Hararit beautiful both inside and outside.

Anzhel Wagenstein:

It is very difficult to find a woman who is both very beautiful and very intelligent.

One may note the hint of condescending misogyny in Wagenstein’s statement. More important, the exchange avoids entirely what might have constituted a thorny issue: the Israeli nationality of the actress. The film was produced at a time when the Cold War was again at its height. Although Bulgaria and East Germany enjoyed rather cordial relations with Israel because the Jews of Bulgarian citizenship had not been deported and East Germany was trying to distance itself from the Nazi past, it is likely that the party elites in both countries regarded the recruitment of an actress from a country closely allied with the United States with a certain amount of distrust. Could this be the reason why director Wolf later complained about the lengthy delays in the signing of a contract with Haya Hararit? In any case, the project fell through: “The choice of the actress […] became complicated”, council member and filmmaker Hristo Ganev later recalled, “because the scriptwriter and the director were unanimous in their preference for Haya Hararit and together with the artistic council had approved her candidacy. She was a Jewish actress, who however later signed a four-year contract with Hollywood and preferred to play in Italy and in America.” Following this unwelcome turn of events, “the comrades, who were authors of the film, took immediate measures […] and sent people to Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary to do screen-tests with actresses there”. The results were disappointing. The challenge facing the actress was indeed significant. As Hristo Ganev further explained, “We need to keep in mind that, from a strictly mechanical and arithmetic standpoint, Ruth does not have a very strong role in terms of film footage; for this reason, a very skilful actress is needed who will linger in the viewer’s mind and make sure that her influence over Walter will be perceived as a subtext.”

Later attempts were made to convince Tatyana Samuilova, who had recently won acclaim for her role in “The Cranes Are Flying” (Letyat zhuravli), a Soviet film about the Second World War that received the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1958. In the end, the role was given to a Bulgarian actress, the young Sasha Krusharska, a student at the Theatre Academy in Sofia. Ruth was her first major part. Although more experienced as actors, her partners were also new to the world of motion pictures: Erik Klein/Kurt (1926–2003) had started a theatrical career with Brecht’s Berliner Ensemble in 1954, whilst Jürgen Frohriep/Walter (1928-1993) had been involved with the Berlin Theater der Freundschaft since 1951.

In the film, Ruth appears in five scenes (out of 17) most often sharing a frame with Walter. She exhibits an agency of her own only in one of the first scenes with her when, already incarcerated in the camp, she rushes to the barbed wire to ask the German Unteroffizier Walter, who is walking nearby, to fetch a doctor for a Jewish woman in labour (illus. 1). Her next key encounter with Walter occurs at the initiative of Kurt, who, during a drunken evening in a tavern, asks a guard to bring a Jewish (female) prisoner to his friend. Although far from sober himself, Walter saves Ruth from Kurt’s potential sexual assault by kissing her and taking her out for a walk. In fact, two kisses delimit the window of time the would-be couple is allocated in the plot: while the first one is imposed on Ruth, she consents to the second one, a few hours before the transport leaves. Apart from these moments (and even during them), Ruth is construed as a pure and devoted motherly figure, first, for the Jewish children in the camp, whom she tries to distract from the screams of the woman giving birth; second, for her own father, who refuses to see that the deportation means certain death; and finally, she acts as mother for Walter as she tries to instil in him self-confidence and the will to strive.

The extreme sobriety of her clothes (a dark dress, at times a veil at night), the intense light with which her face is frequently illuminated (to the point where her features disappear behind her wide-open eyes, creating the impression of an Orthodox Christian icon) and the numerous close-ups on her blank face conjure up images of sanctity. Often shot in a three-quarter portrait in compositions set diagonally, with her face looking up to the sky, she seems to offer a receptacle for others’ lives and intents. The leitmotiv use of superimposed frames magnifies this effect. This situation is most remarkable at the moment when the camera shows her smiling as she hears the cries of a new-born. The close-up of her face, shining as if with heavenly delight, fades into the image of a cascade in the midst of a mountain forest. At the most tragic moment in the movie, when Ruth stands behind the bars of the departing train, her gaze lost in the distance, the lyrics of the Yiddish song “It Is Burning”, which is heard in the background, are written upon her motionless face like ink on white paper.

Were the director of photography and the filmmaker aware of the religious symbolism they were conjuring up and of the association between womanhood, motherhood, and sacrifice? To what extent were they following interwar cinematic traditions or yearning to break with the aesthetic codes of socialist realism? Should we consider the possibility that these visual choices illustrate a then-dominant understanding of the Holocaust and of Jewish responses to persecution (read: a supposed lack of response)? Literary critic Nesho Davidov’s film review suggests that the last hypothesis might be valid:

If we exclude Ruth for now, not a single full-blooded image emerges from the Jewish masses. […] The mother, the elders, the kids – all are reduced to a crowd of people crushed, featureless, who have lost all possibility to show human dignity, mingled, resigned and submissive like cattle to the slaughterhouse. […] the viewer is appalled. But something is missing. He longs to see a hint of resistance, however small it might be, in these people. Even the man sentenced to death, when he is led to the gallows, makes a move backward. Whereas these people, they go, go.

The character of Ruth could have been expected to offer a counterpoint to this undifferentiated portrayal, Davidov argues further:

She could and should have fled the Jewish group. She is young, she is intelligent. In her, the urge to live cannot be easily choked. […] She is conceived as a pro-active, living image, albeit with a sporadic, not fully conscious striving to stay alive as long as possible. We understand her and even believe that, were a possibility to arise, she would adopt a more active position and be prompted to fight. And this is why we quickly come to like her. But then come the walks and talks with Walter. In a melodramatic and declamatory tone, she speaks of people, of future people who will be good, of crickets and stars … And that’s it. How surprising to see a young girl whose will to live is completely blunted and who believes that the only option available to her is to die alongside her fellow Jews. In this way Ruth remains at the same level as the rest of the group. […] All she does in the film is to emphasise the tragic inevitability facing the whole Jewish group.

Davidov contrasts the depiction of the Jews as defenceless and passive unit with an alternative model of Jewishness – which was offered by the communist Jews who engaged in active resistance during the war. In his review, Davidov leaves the realm of cinematic fiction to evoke a “true-to-life” episode: “Somovit, 1943. A situation and conditions nearly similar to those in the film.” He then tells the story of a decision made by internees to give the young and the healthy the best portions of food so that they could live longer: “The story is true, and, I believe, heroic.” This move is eloquent: In the 1950s, in the publicly sanctioned Bulgarian historiography on the war, a master narrative about the fate of the Jews had started to take shape. That narrative centred on the rescue of 48,000 Bulgarian Jews who had escaped deportation thanks to public protests in the spring of 1943. By the late 1950s the various anti-Jewish measures such as professional exclusions, Aryanisation of Jewish properties, expulsion from Sofia and other large cities in 1943 and enrolment in forced labour battalions, which had been (partially) documented by the People’s Court in 1945, had started to disappear from public discourse. The specific Jewish experience of the war was thus noted only in scholarship eulogising the Jews who had fought and died in the anti-fascist struggle.

Nevertheless, to grasp the specific fashioning of Jewish victimhood and agency in the movie, one may need to move beyond the confines of Bulgaria or, for that matter, the GDR. The interpretation of the Holocaust that contrasts the “praiseworthy” resistance of communist Jews with the “regrettable” lack of initiative of (non-communist?) Jewish victims bears undoubtedly the stamp of socialism. Yet attempts to liken Jewish victims to “cattle going to slaughter” were not exclusive to the Eastern Bloc. These images haunted discussions of the Jewish genocide throughout the world well into the 1970s. Moreover, in its articulation of gender stereotypes (female passivity) and cultural stereotypes (Jewish passivity), Zvezdi/Sterne taps into a historical tradition whose roots predate the establishment of state socialism. Ultimately, I wish to argue that the movie bears witness to the crystallisation of common tropes in the representation of the Holocaust beyond East and West. One more piece of evidence will illustrate this point: the symbolic wrapping of Jewish suffering in a Christian veil, a move that one would not have expected from filmmakers committed to a Marxist reading of history.

3. Downplaying the Specificity of Jewish Destinies? Love and the Holocaust in the Shadow of the Cross

Both Bulgarian and East German officials were eager to lend the co-production the widest possible international appeal. As a newly established state, the GDR sought international recognition for its cultural achievements. DEFA insisted that the film be ready for the 1959 Cannes Film Festival, and therefore the Bulgarian and German teams worked on a very tight schedule. The feature film was to demonstrate that it was possible to be German in an East German way. It was also instrumental in the East German leadership’s aim to denounce the alleged fascist restoration in capitalist West Germany. To some extent, Anzhel Wagenstein and Konrad Wolf had a different agenda from their respective leaderships: They wanted the Jewish catastrophe to be known and remembered. This commitment stands out in their comments during the discussions of the artistic council. They were amongst the few participants, who explicitly regarded the annihilation of the Jews as the central theme of the movie and tried to tie it to the anti-fascist credo of the time. As Anzhel Wagenstein put it during the 5 January 1959 meeting:

Fascism in our film is not expressed through the character of Kurt alone. Fascism also manifests itself in these 8,000 Greek Jews who were sent to Auschwitz. Only one woman returned, one who was sent to a whorehouse. That is fascism. The reason why, during the wartime, the people of Walter’s kind did not change the course of events is precisely the reason why Walter does not manage to stop the course of the train, i.e. because they become aware of the need to stop the train much too late […]. It is not enough to wish something to happen, one must make it happen. In this way we have […] wanted to make a film that speaks to the audience of today.

Both artists were committed internationalists. One of their most audacious decisions in this respect is to shoot the feature in several languages (German, Bulgarian, Greek and Ladino) with subtitles. However, their effort to universalise the portrayal of the Jewish tragedy followed unexpected paths at times, as they used a very specific kind of religious iconography.

In the previous section of the article, I have alluded to the motherly presentation of Ruth’s purity. But there is more to the story. The love between Ruth and Walter develops as they wander in the darkness of night up the hills of a tiny provincial city, whilst the whirling wind drifts clouds above their tormented heads. At the beginning of their first walk, the two wanderers pass a Christian cemetery. The avenue of crosses created by the graves symbolically echoes their discussion about the death of the Jewish baby Walter hoped to save and prefigures his failure to rescue Ruth. During their last walk, the religious symbolism becomes even heavier, as the couple seeks refuge in a church. “People say that everyone has a good star”, Walter murmurs as they walk ceremonially towards a large cross mounted on a stone façade outside the church. “And when it is taken away, the person dies”, Ruth responds softly. Pointing to Ruth’s yellow star, Walter bends over Ruth’s angelic face to deliver a kiss.

The use of Christian iconography (crosses, churches, visual iconography evoking Virgin Mary) to represent the annihilation of the Jews did not elude the film’s assessors in the artistic council. On 5 January 1959, following a screening of the movie, some raised the issue:

Valeri Petrov (a famous Bulgarian poet and writer of Jewish descent):

One feels the presence of symbols, which may not have been placed there to convey a particular symbolic significance, but which nevertheless emanate symbolic meanings. For instance, during a walk the two main protagonists reach a church. This image of the cross and of the two characters – the man and the woman – nearing it, at such a crucial moment and in footage devoid of text, may suggest more than the authors of the film intended. It may be closer to a line – you see which one – which is not to be wished for […]

Yako Molhov (a Bulgarian Jewish scriptwriter, author, and critic):

To some extent, the cross is supposed to unite those who are already in love. The cross is neither the most adequate symbol in this situation, nor is it in harmony with what we want to say about these two characters.

Nikola Mirchev (a Bulgarian painter and illustrator married to Bulgarian Jew Lisa Leon):

I suppose we should have put a five-pointed star here (in this scene)!

Yako Molhov again:

It does not work; this cross is not suited.

The criticism of the members of the artistic council targets the use of religious symbols. But it does so in a very specific, elusive, evasive and understated way. What is stigmatised is the presence of confessional markers in a movie designed to buttress the socialist identity of the audience. None of the Jewish participants in the discussion denounces explicitly the use of Christian symbols to characterise Jewish suffering. None of them calls for recognition of the singular Jewish experience of the war.

Zvezdi/Sterne was not the first post-war feature to resort to this visual ploy. In a fascinating essay on early representations of the Holocaust, art historian Stuart Liebman recently suggested that an iconographic standard had emerged in the years 1944 to 1946 in both the West and the East which employed Christian iconography to promote a universal understanding of the Holocaust and feelings of empathy for the plight of the Jews: The Americans used it to convince a reluctant public of their righteous involvement in the war, the Poles for fear of reactivating antisemitism, the Soviets because they viewed the narratives of “the Jewish Holocaust and the Great Patriotic War as a zero sum game” and were also aware of the attachment of the people to Orthodox Christianity. To express the unfathomable, Western and Eastern filmmakers and cameramen mobilised the aesthetic idioms they deemed most likely to favour identification across religious and ethno-cultural groups. Most of these artists were Jews or were classified as such under the Nuremberg race laws (Aleksandar Ford, Roman Karmen, Alfred Radok, Jerzy Bossak, and others). They were also devoted communists who believed in a new political order that extolled human brotherhood and transcended earlier divisions between Jews and non-Jews.

To a large extent, the trajectories and beliefs of Anzhel Wagenstein and Konrad Wolf resemble those of their forebears. Both were born into Jewish communist families who had fled their countries to avoid political repression in the interwar period. The Wagensteins migrated to France; the Wolfs opted for the USSR. Wagenstein and Wolf tried to relate the specificity of the Nazi genocide, whilst navigating between their self-definitions as Jews and their wish to frame their experience in socialist terms. One might have expected this socialist commitment to lead to the avoidance of all religious symbols. This, however, was not the case.

In the last resort, when considering the making of Zvezdi/Sterne and its particular way of intertwining gender and cultural stereotypes, one must look beyond the particular artistic career of Konrad Wolf and beyond the anti-fascist tradition of DEFA movies. Bringing scriptwriter Anzhel Wagenstein, the Boyana Film Studio, and political contingencies in Bulgaria back into the picture offers additional insight into the conception and production of the feature. But the story of the making of Zvezdi/Sterne has a much broader resonance: It tells us about the transnational construction of visual and symbolic codes that transcended the geopolitical and political borders of the Cold War in the decade following the war.

Those who wish yet another illustration of this global embrace may turn to Tito’s non-aligned Yugoslavia. In 1960, Jewish filmmaker Frances Shtiglitz directed “Deveti Krug/The Ninth Circle”, the first Yugoslav film devoted to the Holocaust in Croatia. The film narrates the story of a doomed love between a Jewish victim, Ruth, and a Christian hero, Ivo, a young Croat. As in Zvezdi/Sterne, the two characters are brought together and separated by the war. Here, too, the heroine perishes in the end. In 1960, the movie was awarded first prize at the Pula Film Festival. Frances Stiglitz’s speech on that occasion ignores the Jewish identity of the victims:

I was keenly interested in the screenplay “The Ninth Circle” because of its deeply moving theme about the destiny of a young love in the rage of World War II. No doubt the human aspect of the story as well as the possibility to offer a poetic treatment of a young love and a counterpoint to the dark waves of inhumanity evident in the last war was what I considered most necessary in the film.

In Poland, the Yugoslav film was released with a poster by Franciszek Starowieyski which shows a Jewish woman on … a crucifix. Once more, the depiction of Jewish female victimhood draws together the gender and the cultural stereotypes of the time.