Baltic-German queer

Vikerkaar 3/2024

Queer histories in Estonia(n): featuring 19th-century writing defying heteronormative expectations; why ‘cis-gender’ is a useless concept; Russian-speaking LGBT+ activism; and a history of trans rights in Spain.

The latest 2000 looks at the intersection between art and ethics, remembering forgotten Jewish-Hungarian star actor and theatre director Jenő Janovics, asking whether the greatest form of cowardice is to unquestioningly obey unjust authority figures, and taking another look at a photo-portrait of Marcel Duchamp that makes us reconsider the artist’s genius.

After Transylvania was attached to Romania in the Versailles treaty in late 1919, the Cluj-Napoca Hungarian State Theater put on a final performance before being forced to leave the building. The play was Hamlet and the show turned into a protest, lasting until late at night. ‘Records say the audience answered, “To be or not to be” with a loud “We want to be.”’

After Transylvania was attached to Romania in the Versailles treaty in late 1919, the Cluj-Napoca Hungarian State Theater put on a final performance before being forced to leave the building. The play was Hamlet and the show turned into a protest, lasting until late at night. ‘Records say the audience answered, “To be or not to be” with a loud “We want to be.”’

Disturbing patterns of historical erasure surround the memory of the performance, writes Andrea Tompa. By the time northern Transylvania was reconquered by Hungary in 1940, the star of the show, the Jewish actor and director Jenő Janovics, had been removed from the history of the institution. When the theater was ceremonially re-opened, Janovics provided most of the items for a commemorative exhibition, without his name being featured at all. Similarly, an article he wrote on the history of the theatre appeared under the pseudonym, with his consent, because the Second Vienna Accord forbade him from publishing.

András Czeglédi draws on Timothy Snyder’s ‘first commandment’ in his book On Tyranny – ‘Do not obey in advance’ – to examine the nature of cowardice and obedience. In an essay of ‘meta-ethical musings’, he recalls everyday cases of people disobeying Nazism and getting away with it – among them the famous photograph of a young mechanic refusing to perform the Nazi salute in a crowd of his colleagues. Czeglédi contrasts the ethics developed in the work of Mikhail Bulgakov with the practical immorality that the human species often needs for pure survival. Cowardice, he argues, is part of us. But ‘the cowardice of obeying in advance is the greatest sin’.

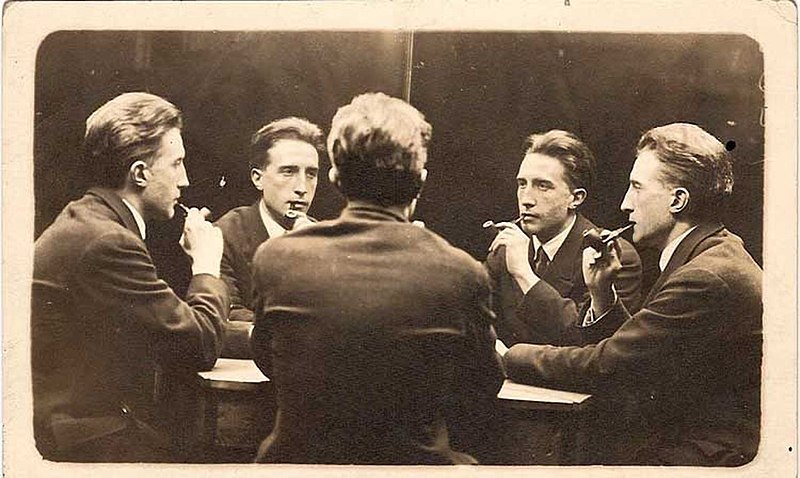

Marcel Duchamp, Five-Way Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, 1917, Gelatin silver print, Photographer unidentified, Private collection, courtesy of Francis M. Naumann Fine Art via Wikimedia Commons

Art historians have recently been fascinated by a photo portrait of Marcel Duchamp, in which the artist is depicted fivefold, as if in a conversation with himself around a table. Since its exhibition in 2009, the photo has been read as a trace of Duchamp’s formerly overlooked unique genius. András Beck traces the history of the peculiar five-way composition, only to find that it was a popular genre of fin de siècle photography, achieved by setting up two mirrors at a 72-degree edge. This places the critical acclaim around Duchamp’s portrait in a somewhat different light, writes Beck.

More articles from 2000 in Eurozine; 2000’s website

This article is part of the 19/2019 Eurozine review. Click here to subscribe to our reviews, and you also can subscribe to our newsletter and get the bi-weekly updates about the latest publications and news on partner journals.

Published 7 November 2019

Original in English

First published by Eurozine

© Eurozine

PDF/PRINTSubscribe to know what’s worth thinking about.

Queer histories in Estonia(n): featuring 19th-century writing defying heteronormative expectations; why ‘cis-gender’ is a useless concept; Russian-speaking LGBT+ activism; and a history of trans rights in Spain.

Two years have passed since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. Those defending against continued aggression, displaced from their homes and previous lives, deal with daily, compounded loss. Artists, reflecting on the trauma, tackle the questions that aim to make sense of life when everything is affected by death.